A Transindochinois express train headed by a Hanomag 4-6-2 “Pacific” locomotive passes the Corniche de Varella at km 1231, close to the site where the final stretch of track was laid on 2 September 1936

Friday 2 September 2016 is an auspicious day in the history of Việt Nam’s railways, marking as it does the 80th anniversary of the completion of the “Transindochinois” or North-South railway line.

Paul Doumer, Governor General of Indochina 1897-1902

Originally the brainchild of Indochina Governor General Jean Marie Antoine de Lanessan (June 1891-December 1894), the “Transindochinois” did not become a reality until the arrival of his successor Paul Doumer (13 February 1897-October 1902), who made it the central component of his grand “1898 Programme.”

While several of Indochina’s early railway and tramway lines were farmed out to private companies to build and operate, the Transindochinois was conceived from the outset as part of the government-run Chemins de Fer de l’Indochine (CFI) network, commonly known as the Réseaux non concedes (non-conceded networks). Built in five separate stages, the 1,730km line took nearly 40 years to realise.

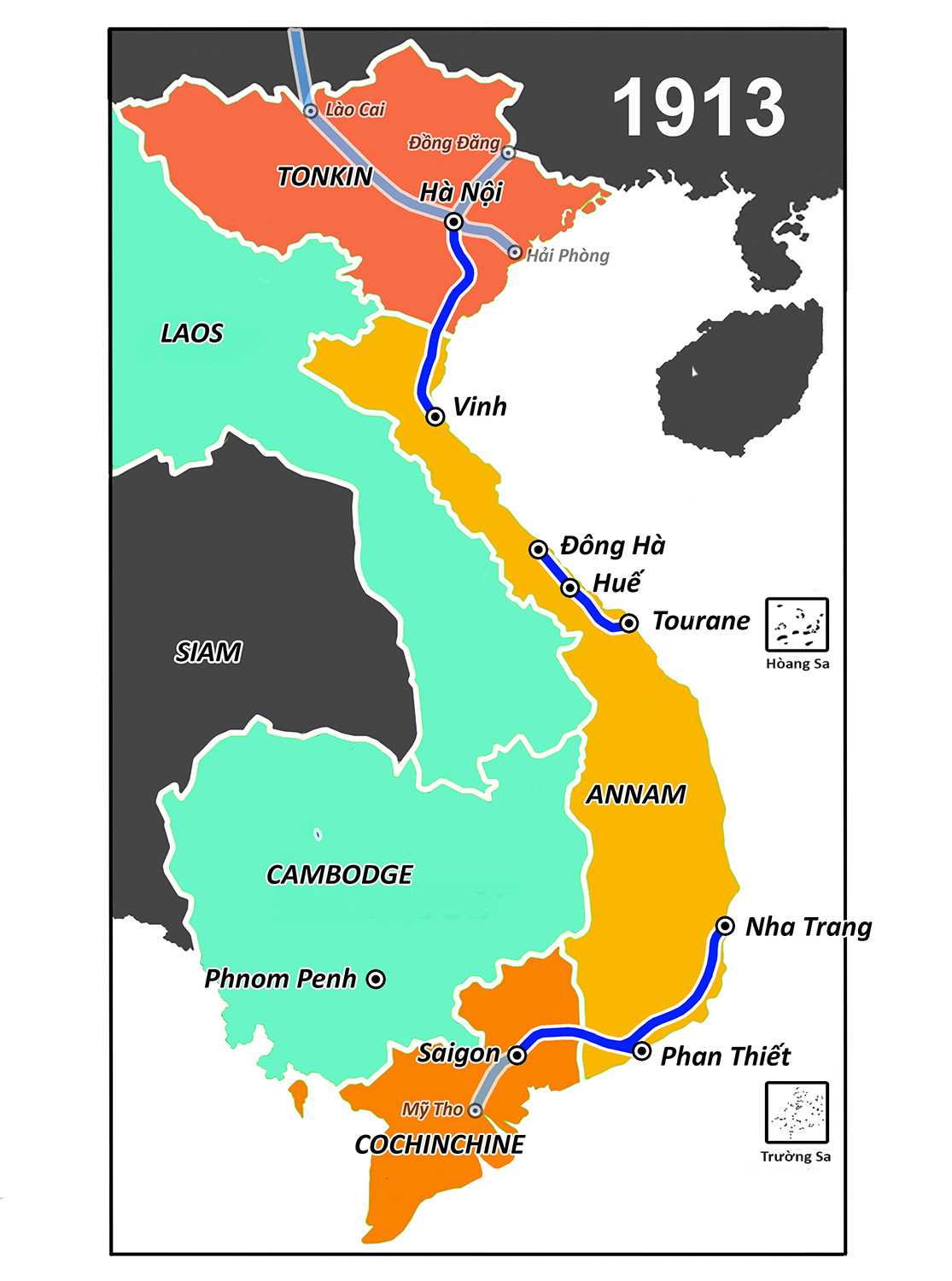

The first three sections of the North-South line were completed before the outbreak of World War I. These were: the line from Hà Nội to Vinh (322km), plus a 4km branch to Bên Thủy port, constructed 1898-1905, inaugurated on 17 March 1905 and costing 43 million Francs; the line from Tourane (Đà Nẵng) to Đông Hà (175km), constructed 1899-1908, inaugurated on 5 September 1908 and costing 32 million Francs; and the line from Saigon to Nha Trang (408km), constructed in 1904-1913 along with the first 40km of Tháp Chàm-Đà Lạt line from Tháp Chàm to Krongpha, inaugurated on 2 October 1913 and costing 69 million Francs. But when the Great War broke out in 1914 there were still two missing links to be filled.

A Société Franco-Belge 4-4-0 “Américaine” locomotive

To haul trains on these earliest sections of line, the CFI initially purchased a fleet of Société Franco-Belge 4-4-0 locomotives, known due to their distinctive profile as “Américaines.” However, these were quickly supplemented by newer, more powerful 4-6-0 locomotives built by the Société française de constructions mécaniques (SFCM), the Anciens Établissements J F Cail and later also the Mitsui Company of Japan.

Known popularly as “10-wheels,” they quickly took over most passenger services, relegating the older “Américaines” mainly to freight duties.

Huế, 1928 – A fourth-class carriage forming part of a Hà Nội-Tourane train stops at Huế Station, Document Archives Nationales d’Outre-mer

The earliest passenger carriages were built mainly from wood and offered rather basic facilities in all classes, but by the 1920s the CFI had introduced into service a range of new metallic vehicles with improved suspension, more comfortable seating in second class, and even plush armchairs in some first class compartments. However, the majority of those using the line were passengers of limited means who were obliged to endure long journeys in what amounted to little more than luggage vans.

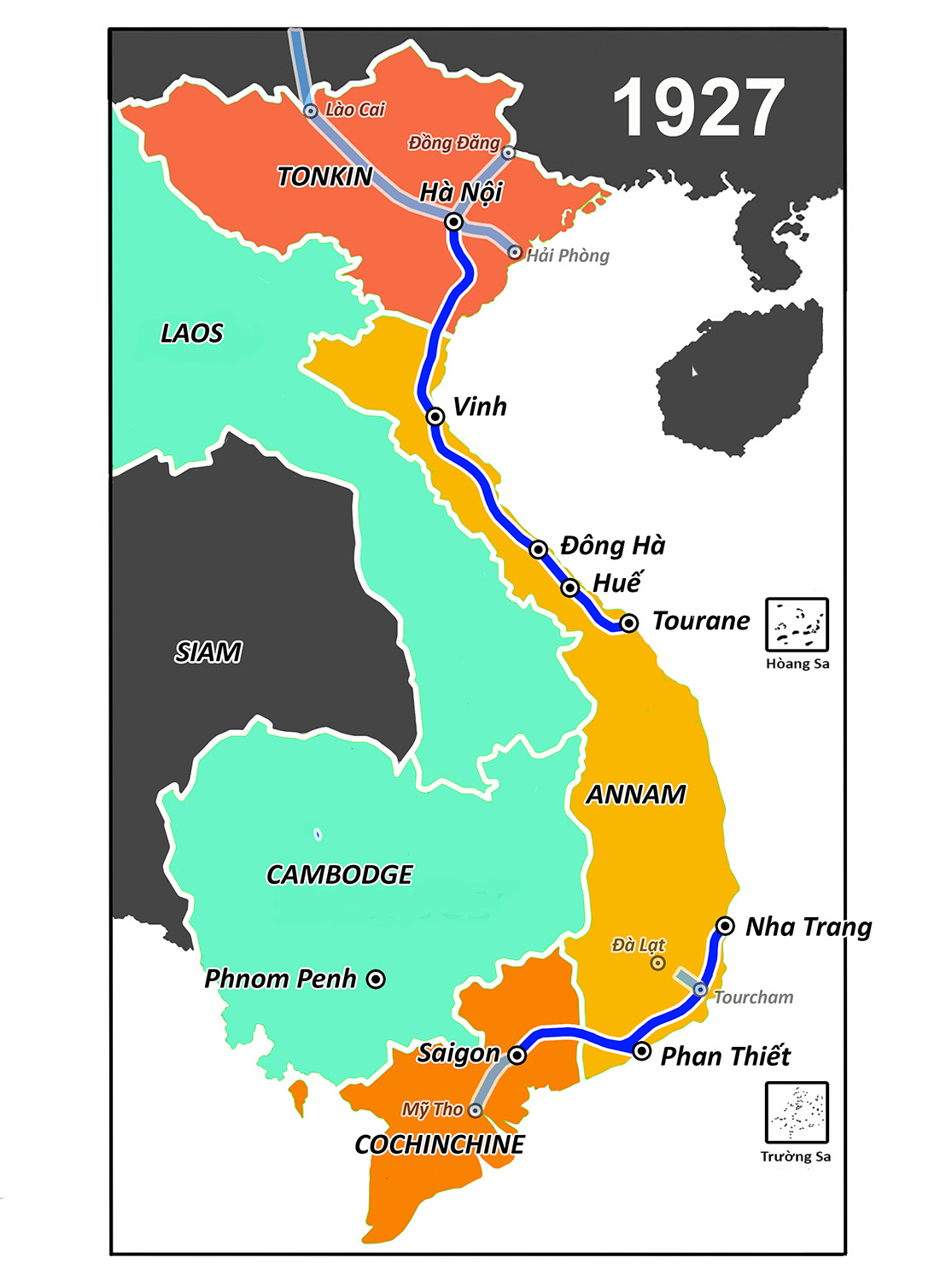

Construction of the Transindochinois was restarted in the 1920s. Commencing construction in 1922, the Vinh-Đông Hà line (299km) cost a further 163 million Francs and was inaugurated on 10 October 1927.

Between 1923 and 1928, in order to meet the increasing demand for faster services on the completed sections of line, the CFI ordered from the Fives-Lille and J. F. Cail companies a fleet of second-generation superheated 4-6-0 “Ten wheel” locomotives, which were shared between the four completed sections of the North-South line and came to dominate passenger services until the arrival in the early 1930s of the “Pacific” locomotives.

A J. F. Cail 4-6-0 “Ten wheel” locomotive

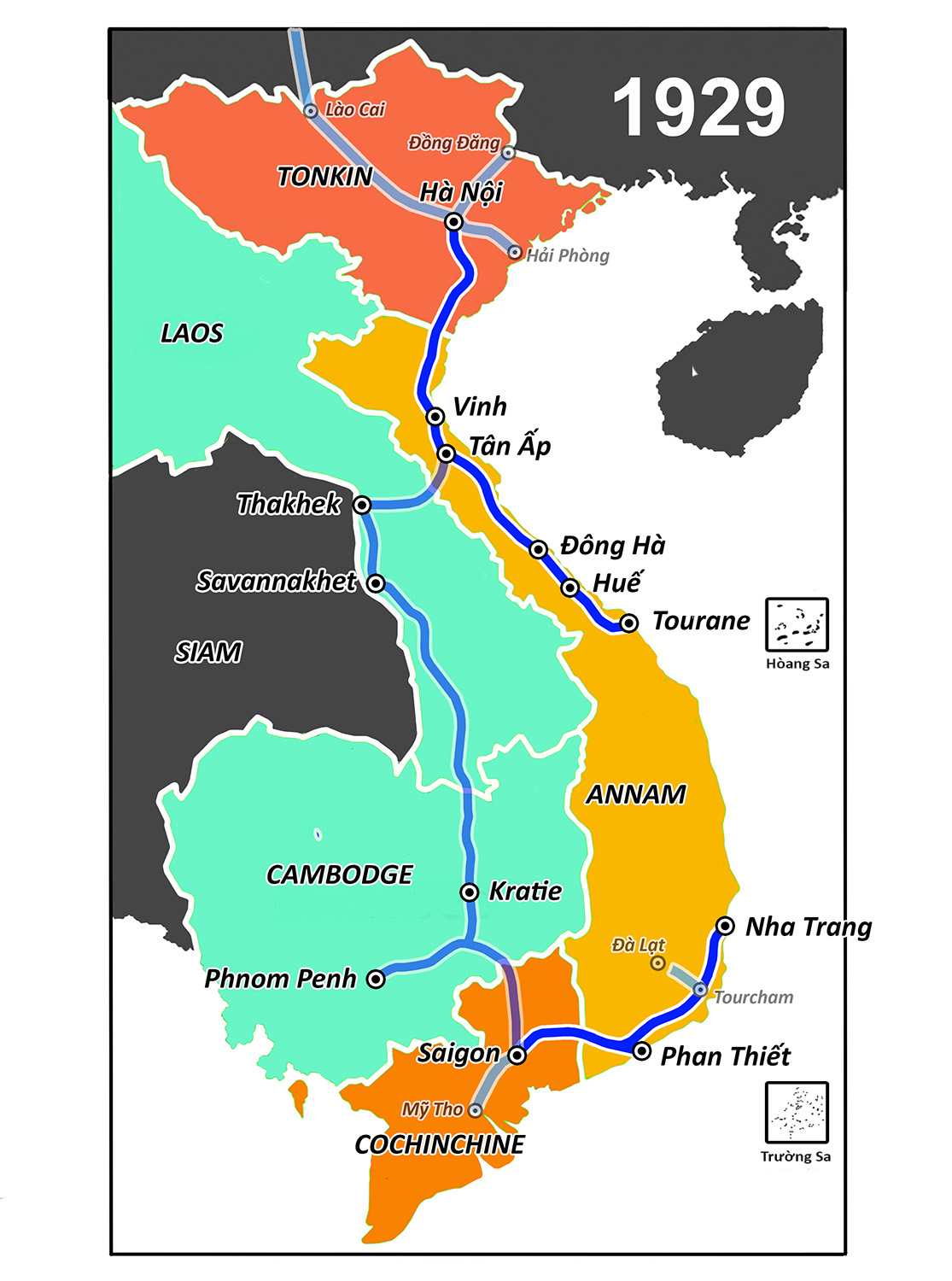

But no sooner had the North-South line project got back on track again than government officials who were concerned about the growing economic influence of Siam over the other two French colonies of Laos and Cambodia came up with a new plan NOT to proceed with the fifth and final stretch. Instead, they proposed completely rerouting the North-South line west to Thakhek and then southward through the Mekong Valley through Savannakhet to Kratie, Phnom Penh and Saigon. However, construction of this new “Grand Interior Route” didn’t commence until 1929, just one month before the Great Economic Crash. The money quickly ran out, and by 1933 the project was abandoned after only a few fragments of the line had been built.

Money was eventually found to complete the final Tourane-Nha Trang section (534km) of the coastal route. However, as construction progressed, the project ran increasingly over budget, eventually bringing the cost of this section of line to a massive 528 million Francs. This would also bring the total cost of building the entire “Transindochinois” to 835 million Francs, some US$20.8 billion in today’s money.

In anticipation of increased traffic following completion of the “Transindochinois,” the CFI purchased a fleet of new superheated SACM-Graffenstaden 4-6-2 “Pacific” locomotives, which immediately took over all mainline passenger services, becoming the most prestigious locomotives on the CFI network.

An SACM-Graffenstaden 4-6-2 “Pacific” locomotive

The CFI also resorted to “filching” the fastest and most powerful locomotives from neighbouring Cambodia – following the reversion of the Phnom Penh-Mongkolborey line to government control in 1935, the CFI embarked upon a controversial locomotive exchange, aimed at “making better use” of Phnom Penh’s Hanomag machines, which they deemed too powerful for the Cambodian railway but ideal for the North-South line. By 1936, seven Hanomag 4-6-2 “Pacifics,” 10 Hanomag 2-10-0 “Decapods” and three Hanomag 2-8-2T locomotives had all been shipped to Saigon. In return, Phnom Penh received a motley collection of ageing Société Franco-Belge 4-4-0 “Américaines,” J. F. Cail 4-6-0 “Ten wheels” and Société Franco-Belge 2-6-2 “Prairies.”

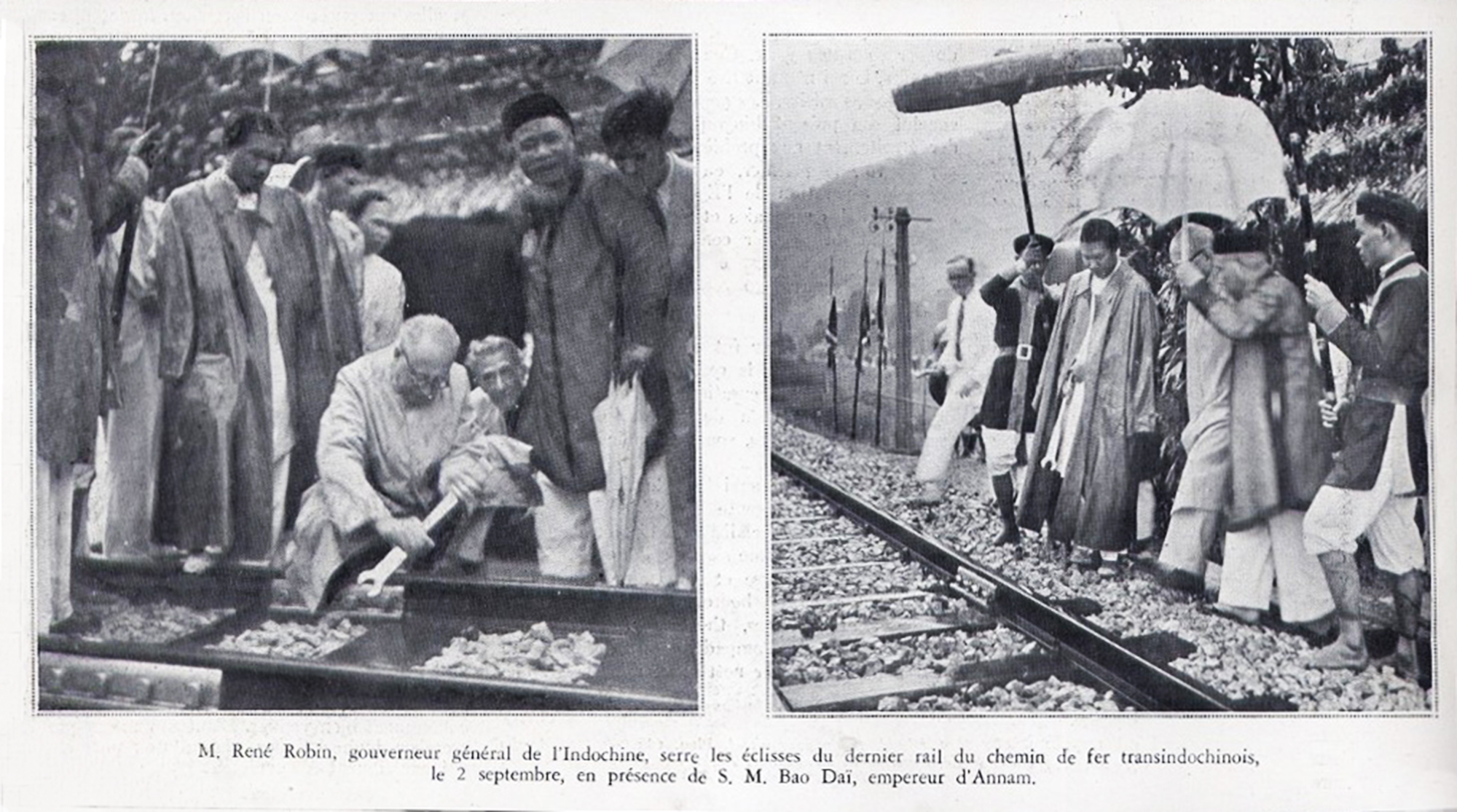

Finally on 2 September 1936, the two construction teams met at Hảo Sơn (km 1221) in modern Phú Yên province, putting in place the final piece of rail which not only connected Tourane with Nha Trang, but also marked the completion of the entire North-South line between Hà Nội and Sài Gòn.

Governor General René Robin accompanies the Emperor Bảo Đại to the completion ceremony on 2 September 1936

Officiating at this occasion were Indochina Governor General René Robin, who had personally sought to fast-track the final stages of construction, and the Emperor Bảo Đại. Later in the month, when Governor General Robin’s posting came to an end, he and his family became the first passengers to make the entire 42 hour, 1,730km journey from Hà Nội to Saigon on a special train, this being the first leg of their long journey back to France.

On 1 October 1936, the last stretch of line from Đại Lãnh to Hảo Sơn was officially inaugurated with the installation of a lineside monument at km 1221, 1km south of Hảo Sơn station. The Emperor Bảo Đại once again presided, along with Acting Governor A Sylvestre and Marshal Long Yun, Governor of Yunnan. The French inscription on the monument read:

“Here, the Transindochinois, conceived by Paul Doumer to seal the unity of Indochina, was completed on 2 September 1936 with the connection of the railway from the Chinese border with the railway from Saigon.”

A “Grand Gala Evening” was held on 2 October 1936 at the Saigon Municipal Theatre

On the same day, trains set out simultaneously from both Saigon and Hà Nội, heralded at both ends by grand military reviews involving processions of ethnic groups in their traditional costumes.

Then, in the seven days which followed, the launch of through train services between Hà Nội and Saigon was commemorated by special celebrations in both Hà Nội and Saigon, funded by a special grant of over 1 million francs. In Saigon, the authorities staged on 2 October 1936 a “Grand Gala Evening” at the Municipal Theatre, attended by Acting Governor Sylvestre. This was followed by a week-long sports tournament known as the “Transindochinois Cup,” which was held in the Jardin de la Ville (now Tảo Đàn Park), and featured cycling, football and rugby. A special commemorative stamp was also issued by the Saigon Post Office to mark the occasion.

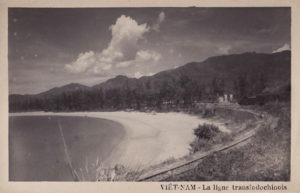

A coastal section of the Transindochinois

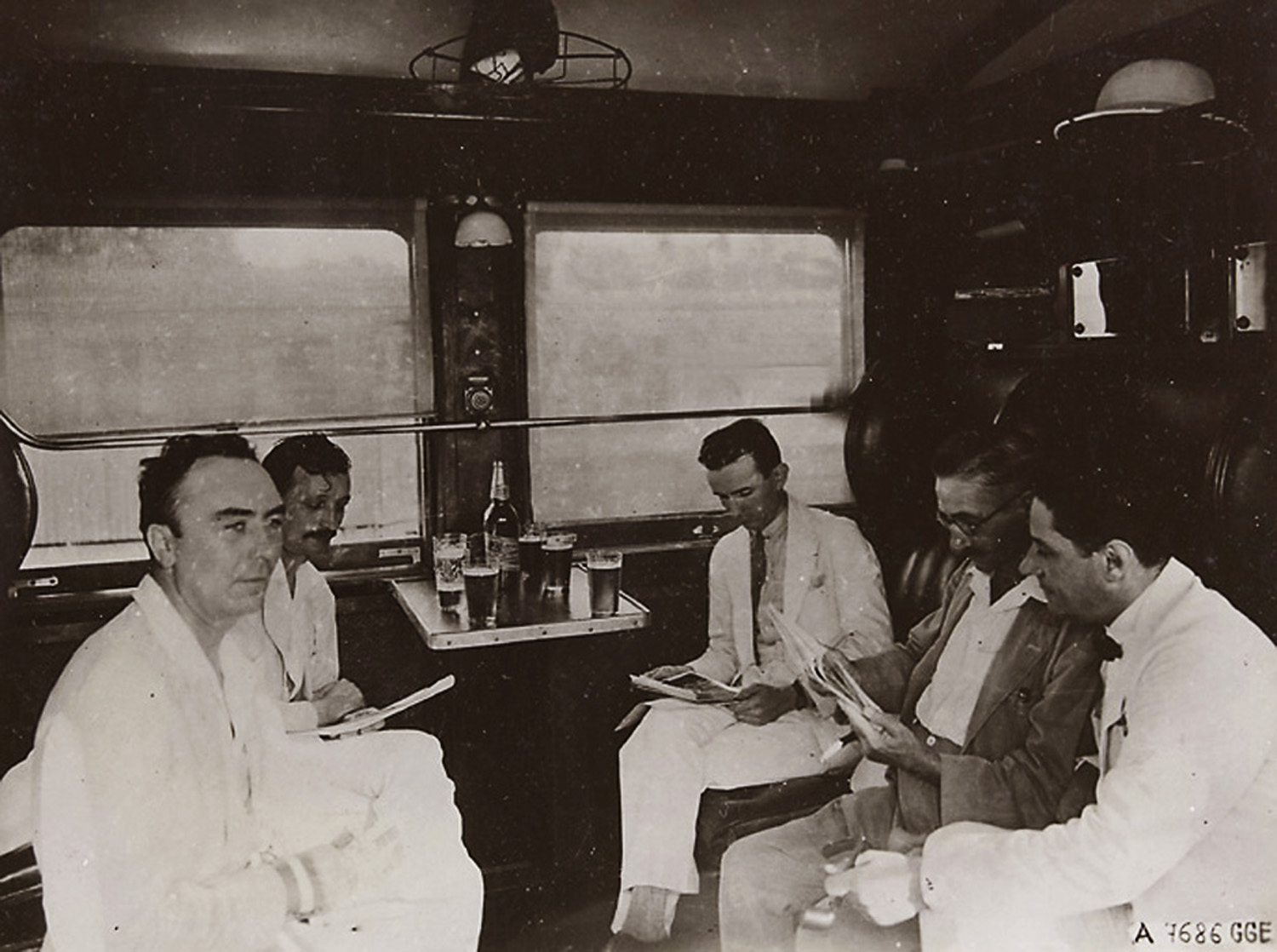

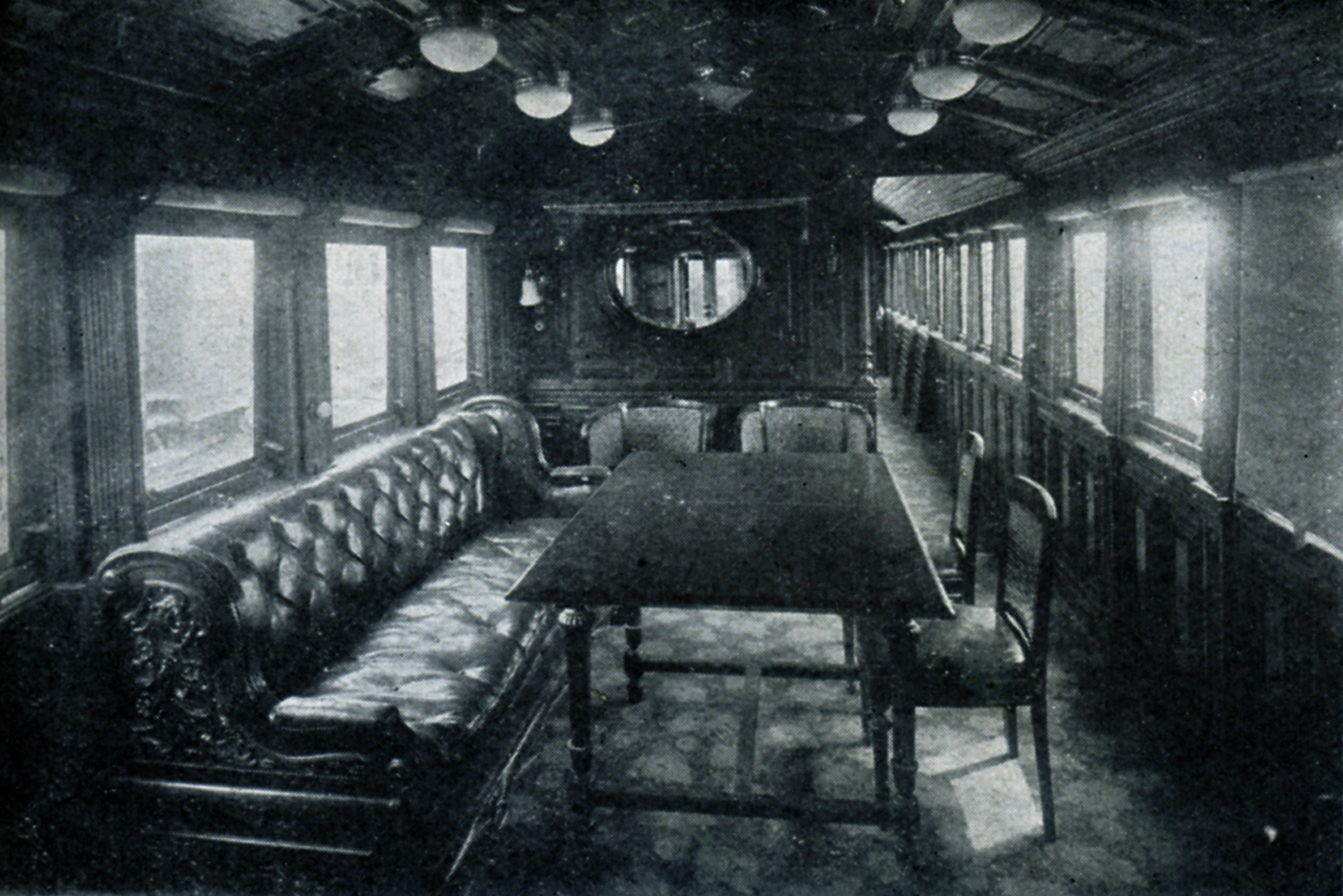

The completion of the “Transindochinois” in September 1936 made it possible to travel 1,730km from Hà Nội to Saigon in 40 hours, on luxurious trains pulled by state-of-the-art “Pacific,” “Decapod” and “Ten wheel” locomotives. The modern and comfortable carriages offered 1st-, 2nd-, 3rd- and 4th-class seating, sleeper compartments and a buffet restaurant, as well as facilities for post and baggage.

Sadly, the “Transindochinois” functioned for just four years before Japanese forces invaded and occupied Indochina, imposing a significant reduction in civilian rail services in favour of military usage. Then, starting with the Allied bombing of 1944 and continuing through the devastation of the First Indochina War, the North-South railway line suffered catastrophic damage.

Railway sabotage during the First Indochina War

In 1952, officiating at the transfer of the remaining operational sections of the Réseaux non concedes to the State of Việt Nam administration, a senior French railway official recalled fondly the pre-war “golden era” of the CFI network:

“The globe-trotter of 1939, making the trip from Hanoï to Säigon in carriages comparable to European wagons-lits, and with a restaurant of repute, could compare our railway favourably with those of Europe or America.”

The Second Indochina War inflicted further ruinous destruction on the North-South line. This was followed after Reunification by several decades of economic hardship which precluded any major upgrade of rail facilities.

While some aspects of today’s rail services may still fall somewhat short of those offered during the “golden age” of long-distance rail travel, the national rail operator Đường Sắt Việt Nam has in recent years sought to create an efficient and competitive national rail network, with the North-South line as its focus.

The first three sections of the North-South line were completed by 1913: (i) Hà Nội-Vinh (322km), inaugurated on 17 March 1905; (ii) Đông Hà-Tourane (175km), inaugurated on 5 September 1908; and (iii) Saigon-Nha Trang (408km), inaugurated on 2 October 1913. But when the Great War broke out in 1914 there were still two missing links to be filled.

The project was restarted in the 1920s and the Vinh-Đông Hà (299km) line was inaugurated on 10 October 1927

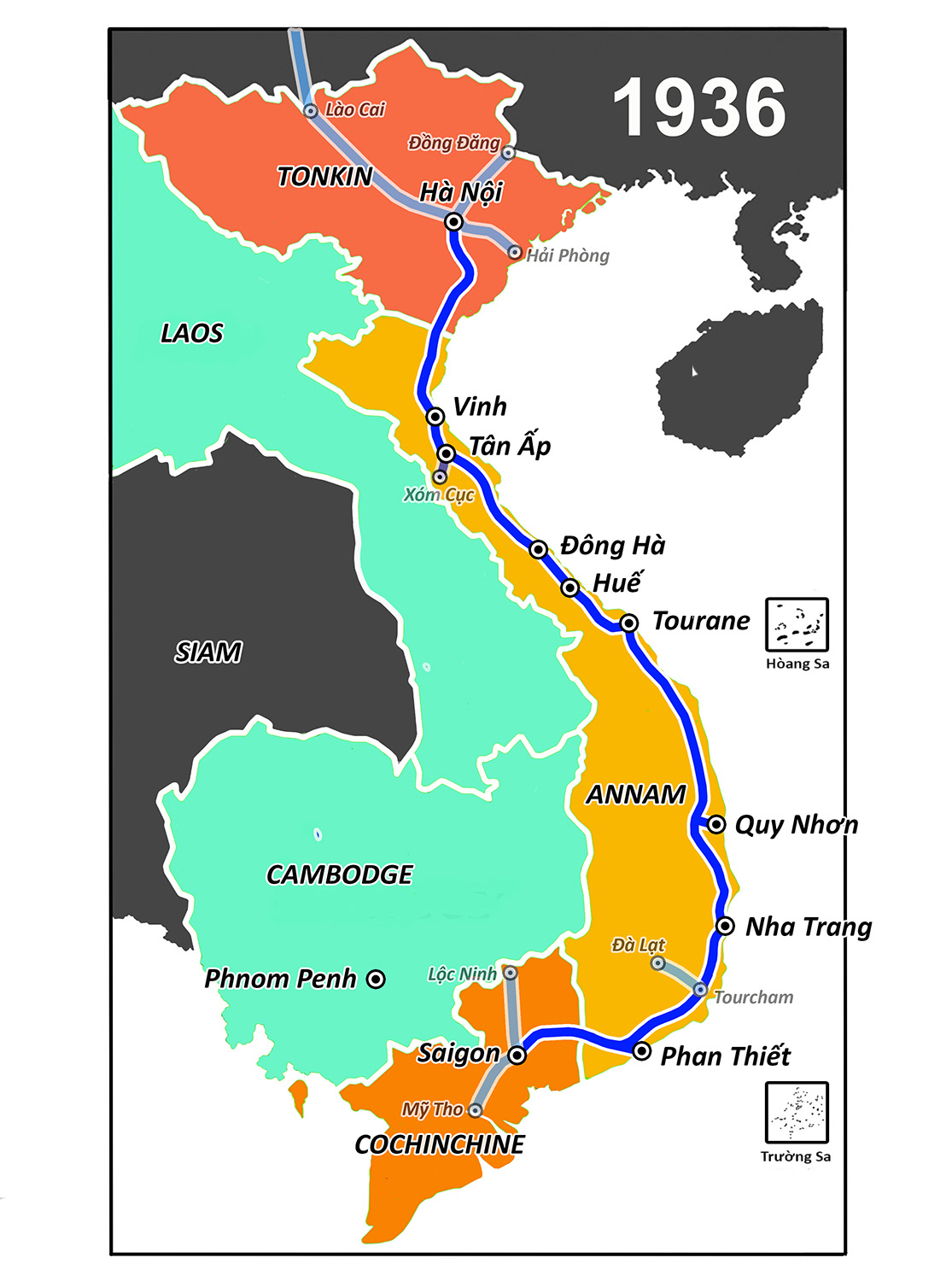

But no sooner had the North-South line project got back on track again than government officials who were concerned about the growing economic influence of Siam over the other two French colonies of Laos and Cambodia came up with a new plan NOT to proceed with the fifth and final stretch. Instead, they would completely reroute the North-South line west to Thakhek and then southward through the Mekong Valley through Savannakhet to Kratie, Phnom Penh and Saigon. Construction of this new “Grand Interior Route” didn’t commence until 1929, one month before the Great Economic Crash. The money quickly ran out, and by 1933 the project was abandoned after only a few fragments of the line had been constructed.

After the failure of the “Grand Interior Route” scheme, the French found the money to complete the final section of the original coastal route by building the Tourane-Nha Trang (524km) section, which was inaugurated on 2 September 1936

On 2 September 1936 at Hảo Sơn (km 1221) in modern Phú Yên province, Governor General René Robin and Emperor Bảo Đại put in place the final piece of rail which not only connected Tourane with Nha Trang, but also marked the completion of the entire North-South line between Hà Nội and Sài Gòn

The lineside monument unveiled on 1 October 1936 at km 1221, 1km south of Hảo Sơn station

The interior of a CFI observation car

The interior of a CFI buffet car

Passengers in a CFI first-class compartment

Part of a CFI first class car

Fourth class travel on CFI

A train from Quy Nhơn arrives at Saigon Station in 1958 behind Hannoversche Maschinenbau AG (Hanomag) 2-10-0 “Decapod” No 150-305, originally purchased for the Cambodia Railway but transferred to Saigon in 1935-1936, photo by Guy Rannou

Tim Doling is the author of The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, Bangkok, 2012) and also gives talks on the history of the Vietnamese railways to visiting groups.

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group Rail Thing – Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam for more information about Việt Nam’s railway and tramway history and all the latest news from Vietnam Railways.