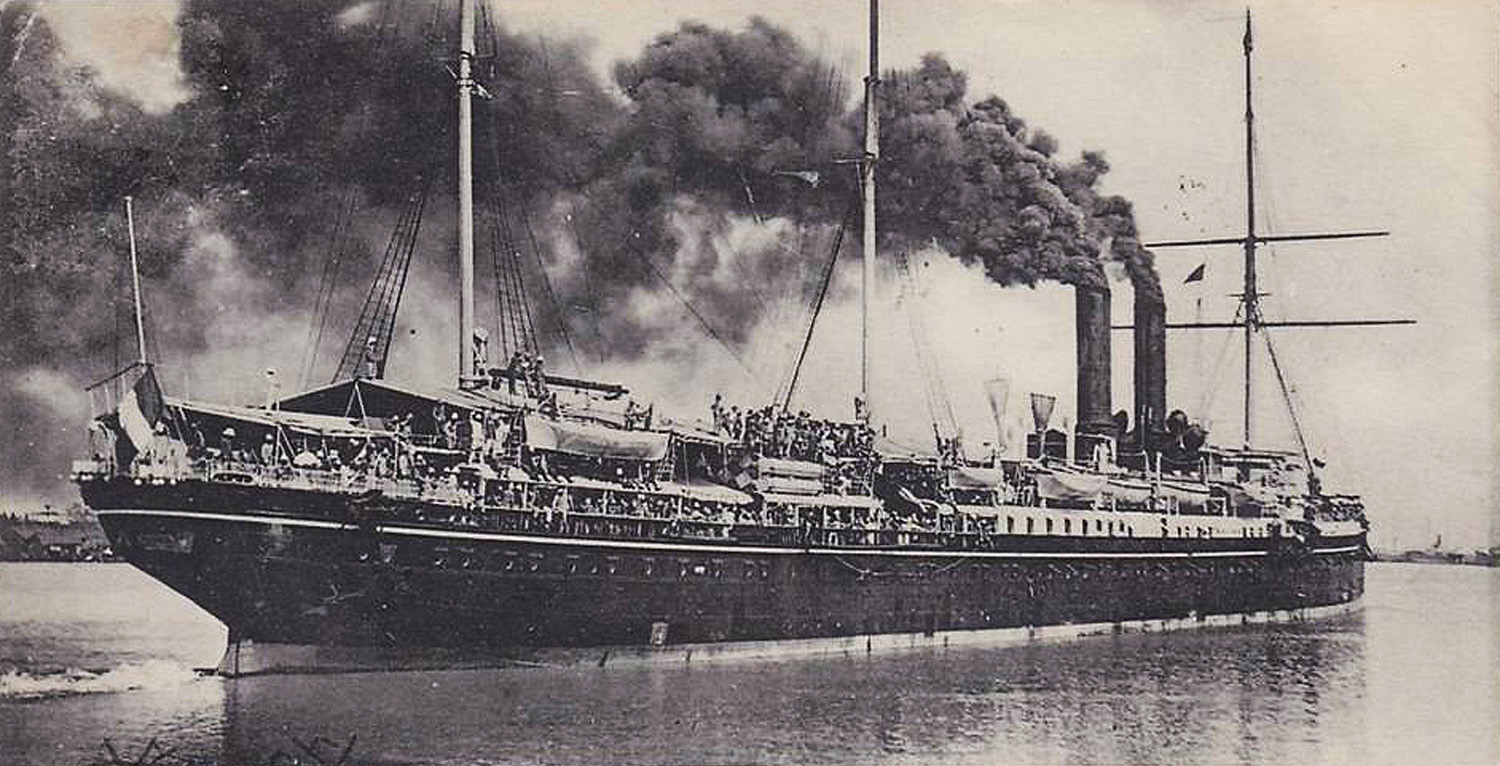

The Messageries maritimes vessel M V Polynésian, pictured in 1914

In early 1912, A Maufroid visited Cochinchina as part of a six-month tour of the Far East. This is an English translation of the chapter entitled “Saigon” from his 1913 book De Java au Japon par l’Indochine, la Chine et la Corée (From Java to Japan via Indochina, China and Korea).

Yesterday afternoon, the Polynésian passed close to high mountains that we first took to be part of the coast of Cochinchina. In fact, they were the islands of Poulo Condor, huge rocks rising from the sea which France turned into a place of exile for the indigenous criminals of Indochina.

A view of the Messageries maritimes wharf in Saigon

By this morning we were in calm waters. The boat moved slowly up the Saigon River. The countryside was very flat and very green. Along the banks, we saw mangrove bushes at the foot of unknown shrubs, and beyond them the rice fields. The greenery, the plain, the light mist over the water which caught the first light from the rising sun, all was reminiscent of Holland.

At 9am, the Polynésian docked at a wooden pier, where around 20 colons dressed in white were waiting for friends from France.

A river of moderate breadth, a smattering of officials meeting colleagues or greeting superiors, the very small amount of activity in a port containing just five or six ships – all of this seemed quite modest when you compare it with the great English ports of Colombo and Singapore. On the horizon there were no factory chimneys, and close to the wharf one could see only clusters of low houses, customs halls and courier offices. It gave the impression of a small, sleepy provincial town.

A Saigon pousse pousse in 1910

Two pousse-pousse – that’s the name given to the rickshaw in this French territory – carried me and my luggage to the Hôtel Continental, the most recently established hostelry here in Saigon.

In fact, this name “pousse-pousse” (which can be abbreviated simply to “pousse,” meaning push) is only really justified in Pondicherry, where the driver really does push a small carriage ahead of him. Here, as in Ceylon, Singapore and elsewhere throughout the Far East, the vehicle is pulled, not pushed.

Unlike the Dutch, our Indochina compatriots do not regard this mode of locomotion as being incompatible with human dignity. The pousse-pousse abounds in Saigon, and its exaggerated number has had the effect of reducing the price of journeys to one of incredible modesty. For just 10 cents (5 French sous – the piastre of 100 cents is worth about 2.50 Francs) you can buy yourself an average-length journey.

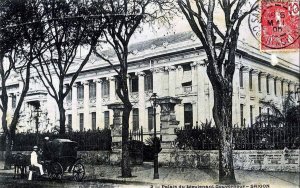

The Lieutenant Governor’s Palace

People rarely walk in the streets. The soldiers themselves spend their time going from barracks to café and from café to barracks and they enjoy prices which are lower than those which civilians have to pay.

Besides, at certain hours of the day it’s so hot that walking is almost impossible for the European, while the “man-horse” – the pousse-pousse driver – runs like a deer, his back cooked by the sun and his skin dripping with sweat.

Saigon boasts of being the most beautiful city in the Far East. This may be true, if by “beautiful” we mean a city which is built to measure and intersected by broad avenues which cross each other at right angles. But for tourists seeking original buildings, or even just the coolness of shadows in the sweltering 32° heat, perhaps the old eastern cities with their bizarre and irregular houses have more to offer.

Gambetta, dressed for Arctic weather

Some of the city’s monuments are very elegant: the Palace of the Lieutenant Governor of Cochinchina on rue Lagrandière; the Post Office; Cathedral square, beautifully landscaped to combat the excessive temperature of the country; and especially the Palace of the Governor General, located at the end of boulevard Norodom, the wide verandahs of which are very well suited to the climate.

One may say the same of a statue which seems almost to menace the Governor General’s official residence with his vehement gestures: a bronze Gambetta, who struggles under a thick coat, like a North Pole explorer. The natives, who sweat all year topless, gaze with amazement at his incomprehensible clothing.

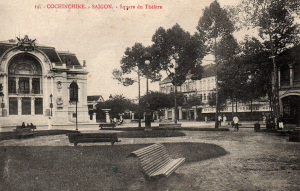

The Saïgonnais would have been unhappy if, over the past few years, they had not built a wondrous theatre. This building stands in the heart of Saigon, a square surrounded by cafés, where rue Catinat, that great artery of the city, joins boulevard Bonnard.

The Saigon Theatre on place Francis Garnier

It cost nearly four million Francs to build, and each year the Municipal Council awards its Director a further subvention of 125,000 Francs, to which is added a tidy sum for artists’ travel.

Along with the cafés which surround it, the Saigon Theatre is the great preoccupation of the Saïgonnais. However, if you take account of the fact that, of its 50,000 inhabitants, Saigon has about 4,000-5000 Europeans capable of savouring comic operas and vaudeville, you will no doubt understand that the evening entertainments laid on here for the colons place a rather heavy burden on the local budget.

Saigon has the appearance of a quiet prefectural town in France which revolves around the lives of its garrison and officials. During the daytime, its spacious boulevards, roasted by the sun, become veritable desert steppes. Each functionary scribbles away all day in an office – unless he chooses to sleep while waiting for the cocktail hour. Then, at about five o’clock, everyone wakes up; the pavement cafés of the rue Catinat fill up with customers; and Theatre square is perfumed with the scent of absinthe. This is truly the magic hour! By this time, the temperature has become more bearable. Friends gather to talk politics while watching the promenaders pass by.

French colons doing the “tour de l’Inspection” by automobile

And how they pass by! An endless stream of people travelling by pousse-pousse, carriage, automobile; in fact, one might say especially by automobile. The motor car, in hot countries, has become a very explainable success. Its speed generates a violent current of fresh air, compared with which the faint breath of the electric fan or the archaic punkah is simply a caress without energy. Here, those who own motor cars may take a tour to the Inspection de Gia-Dinh, along a beautiful road where the powdery dust turns their white suits pink.

After dinner, even more people arrive at the cafés where the orchestras play. Then, during intervals in the performance at the Saigon Theatre, members of the audience come outside and spread themselves all over the square, sitting down at café tables to enjoy iced drinks with grandly dressed ladies.

As soon as a customer is sufficiently refreshed and gets up from his chair in the Café de la Terrasse, the Café de la Musique or the Continental Terrace, up to 20 pousse-pousse drivers immediately gather round him expectantly.

The Grand Café de la Terrasse

As for these pousse-pousse drivers harnessed to their tiny carts, one wonders, seeing their heavy buns of black hair, their effeminate faces, their amphoral hips, whether they are men or women. But these are certainly men … of a somewhat frightening mentality.

When you call a pousse-pousse to go home, the driver will run for just ten seconds before turning to ask “Congaï, Mossié, congaï?” And you answer: No! To the hotel! And make it quick!

And so, the driver once more begins to run. But then, after another 30 metres, he slows and again puts his insidious question. A second refusal, this time even more categorical.

Finally, a little further on, he will amend his offer by asking: “Boy, Mossié, boy?”

I did not attend any performance by the visiting theatre troupe in Saigon. Yet the posters were enticing. The astute director had warned families of character about the particularly frivolous nature of the show.

The Café de la Musique

If this theatre didn’t help me to pass my evenings in Saigon, its presence was not, however, completely without use. As I strolled around the square during one intermission, admiring the grandly-dressed audience members who came outside to breathe the cool air, I was recognised by a lady with whom I had travelled on a steamship two years earlier. Madame P introduced me to her husband, who was kind enough to invite me to dinner the next day and then placed his automobile at my disposal for several refreshing promenades.

It was thus that I went one morning by motor car to Cholon. While Saigon is the bourgeois city, the town of administrators, theatre and cafés, Cholon is the city of business.

Cholon is exclusively Chinese, and has three times the population of Saigon. It is here that the trade in rice, tea, ceramics and various other commodities is concentrated entirely in the hands of the “Heavenly Ones.”

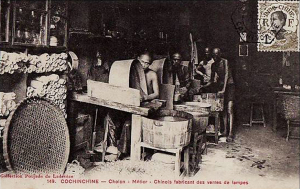

Chinese workers in Chợ Lớn

The city is located five kilometres from Saigon on the arroyo Chinois [Bến Nghé creek]. This river is crowded with junks which are packed tightly against each other alongside rows of rice husking factories.

What I said about Singapore is equally true for Cholon: it is a Chinese colony ruled by Europeans. In the streets, one sees exactly the same spectacle as in Singapore; vertical banners with their golden characters on a black background, and paper lanterns carrying the owners’ names on their flanks.

In the shops – for indeed, most of the houses are shops – the Chinese go about their business wearing only shiny black pants; now that their hair has been cut short [the compulsory pigtail was abolished in China in 1911 following the overthrow of the Qing dynasty], we may see the spot on their necks from where their pigtails were recently excised.

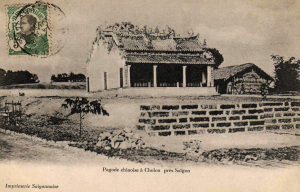

A pagoda in Chợ Lớn

A Chinese employee of Mr P who accompanied me showed me around a few pagodas, which were all very much alike. Their walls were decorated with human and animal figures and flowers made from glazed ceramics, while their angled roof ridges featured dragons with gaping mouths and sharp tongues darting from under slender moustaches. Inside, carved and gilded wooden panels celebrated the names of generous donors. In front of the Buddha statues burned incense sticks, placed in pots filled with ash. The fragrant jostick spirals hanging from the ceilings added their sandalwood fragrance to the scent of the incense sticks.

The Chinese in Cholon include some notorious millionaires. In order to flaunt his wealth, one of them, named Taï-Maïen, had the idea of building a villa which was almost an exact copy of the Palace of the Lieutenant Governor of Cochinchina.

![L0055713 Cochin China [Vietnam].](http://www.historicvietnam.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/8641155529_73c760cd0a_o-300x184.jpg)

The Plain of Tombs

We returned via the Plain of Tombs. A very sad place located in grey countryside covered in tufts of straw, with blackened, sunken gravestones everywhere.

On this side of the city, much of the land is covered in rice fields. Further east, in the direction of Thu-Dau-Mot, many rich Saïgonnais have recently set up rubber plantations, the fruits of which we will be able to appreciate in several years time.

The tomb of the Bishop of Adran, Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine

Between the Plain of Tombs and the Inspection de Gia-Dinh, I stopped for a moment before the tomb of the Bishop of Adran, Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine. In the 18th century, the Bishop of Adran was the adviser and friend of Gia Long, Emperor of Annam. In 1787, through his mediation, the Asian sovereign concluded an advantageous treaty for France.

In his old age, Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine retired to this place, occupying himself by cultivating a small garden. On his death in 1799, he was buried here, and Gia Long raised in his memory an Annamite-style mausoleum, on which one is surprised to see decoration which juxtaposes the Christian cross with Chinese characters and imaginary monsters!

Seeing the tomb of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine reminded me of my own country. In fact, I know several families from his birthplace, the village of Thiérache, to where, I think, I must one day carry some stories about the great prelate who served France so well in far-away Asia.

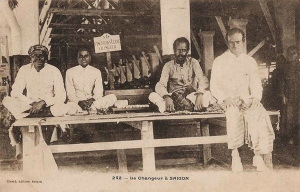

Chettyar money changers in Saigon

While I was in Singapore, I visited an entire neighborhood of Hindu workers, which was not surprising to see in an English colony. In the streets of Saigon we encounter Indian people of a different aspect; these are the Chettyars, who go about naked to the waist, their energetic faces lit by cruel eyes.

The Chettyars are Saigon’s most formidable usurers. They are widely hated in the colony, where they exploit the vices of gamblers and bon viveurs. Anyone who borrows money has reason to use their services. In a country where the normal interest rate in prime mortgage investments is around 8-10%, the Chettyars serve those who do not measure their spending in accordance with their budgetary resources. With such customers, I’m told that some Chettyars demand up to 45% interest on their loans!

“They are a plague!” say many colons. But I say that the plague is not the Chettyars, it is rather the mentality of the borrowers who come to them to pay off gambling debts that no one is obliged to contract, or to pay for disproportionate amounts of luxury which too many French are getting used here as a result of their inexcusable snobbery.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.