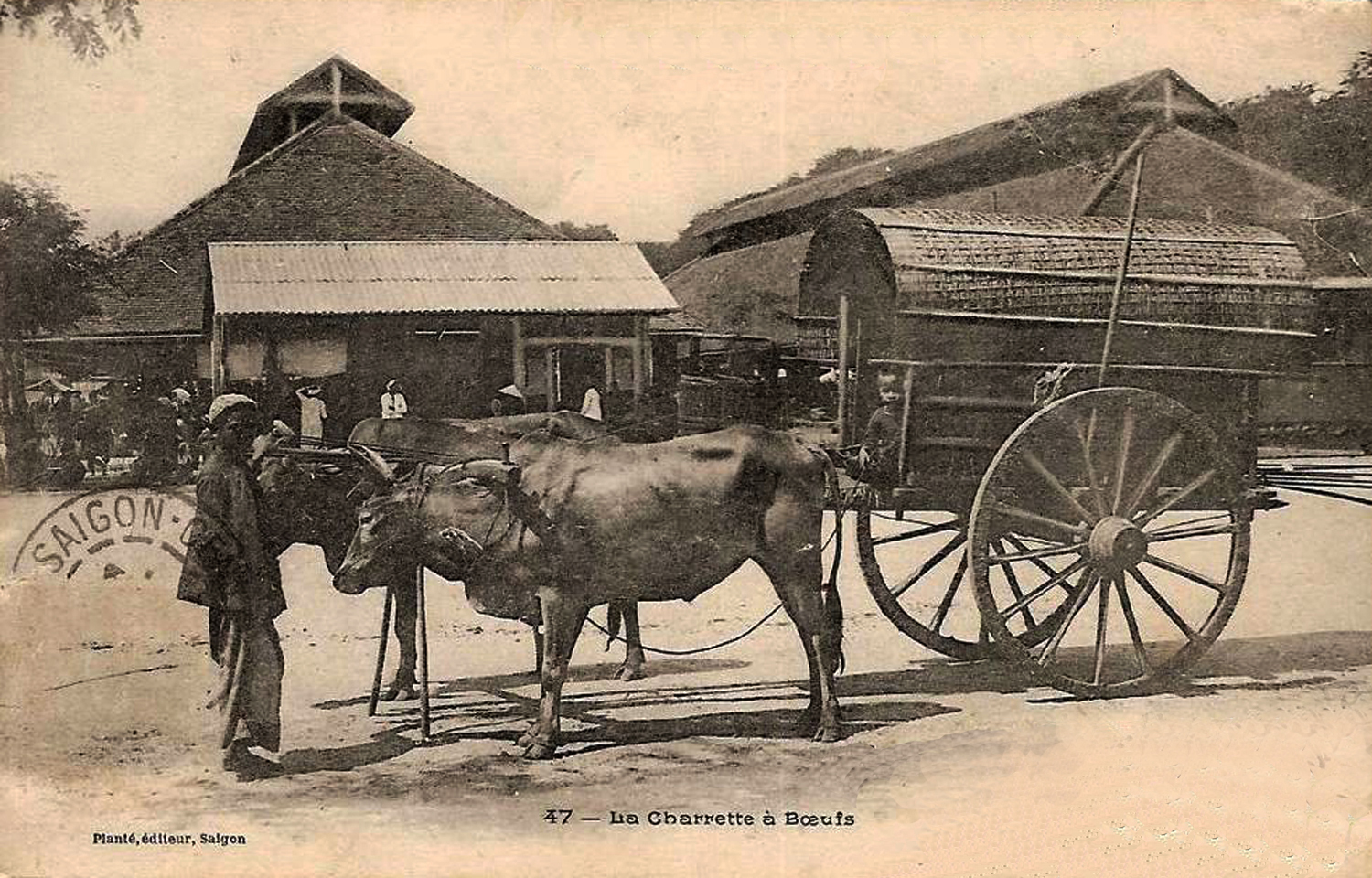

A buffalo cart stands in front of the old market on boulevard Charner (now Nguyễn Huệ boulevard)

In March 1882, Arthur Delteil, retired Chief Pharmacist of the Navy, left Marseille on the Messageries maritimes vessel Oxus and travelled to Saigon, where he stayed for a year. This is the third of three translated excerpts from his book Un an de séjour en Cochinchine: guide du voyageur à Saïgon, published in 1887.

To read part 1 of this serialisation click here.

To read part 2 of this serialisation click here.

From the end of the arroyo Chinois which opens into the Saigon River, we will first cross boulevard de Canton [Hàm Nghi] where may be found the homes of several wealthy Chinese merchants, low wooden houses with no more than two storeys, designed in the particular style of this nation.

The Grand Canal (now Nguyễn Huệ boulevard), the lower section of which survived until 1890

Then we cross a bridge over the Grand Canal, which leads some 200 to 300 metres into the city. On the right and left sides of this canal are the quai Charner and the quai Rigault de Genouilly, and it is on the latter that the city market was built. It occupies considerable space and is divided into four large covered compartments: one is for fish, another for fruits and vegetables, the third for poultry and meat, and the fourth for small industries and local restaurants. The market is frequented by a large crowd of Chinese and Annamese of both sexes, who buy food and often consume it on the spot at their convenience.

In the fish hall, one may see large water tanks filled with live fish; those caught in the arroyos are mud coloured and have a viscous appearance which makes them rather uninviting. Only the Annamite population consumes them; in the language of the country, they are called ca-ro, ca-lac, ca-bong, ca-chiai, ca-gay, ca-hop, ca-tre, ca-tien and luong (eel).

Marine fish, caught in deep waters off Cap Saint-Jacques, have a more appetizing appearance. We may buy many fine species of saltwater fish here, including tuna, mullet, bream, shad, sardine and anchovy. The market also sells delicious clams, winkles, oysters, crabs, prawns and lobsters, which are not inferior in any way to those of Europe. Fish are also caught each year in the great lakes of Cambodia for drying, and these occupy an important place in the market, because they are the basis of Annamite food. These are also used to make nuoc-mam, which I will describe later.

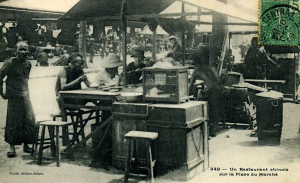

A corner of the old market on boulevard Charner (now Nguyễn Huệ boulevard)

The fruit and vegetable market contains a great variety of products, including bananas, mangoes, mangosteens, cucumbers, cabbages, asparagus and lettuce.

In the meat section, pork dominates; it is of good quality and comes from rather small animals with curved spines and bellies which drag on the ground in a rather unsightly way. The beef costs 7-8 sous per pound and its quality is not bad; eggs cost a few sous per dozen. Game and poultry are very abundant: ducks, green pigeons, plump capons, wild roosters, peacocks, guinea fowl, snipe, quail, hares, wild boars … we are indeed spoiled for choice!

The most curious part of the market is the section devoted to food, and in particular the Chinese food stalls. There you will find a huge variety of the special dishes which are consumed by local people, including every different kind of rice and noodle dish, pastries, roasted duck and suckling pigs adorned with large red peppers. The consumers throng around the stalls and choose from among 10 or 12 dishes which have been spread before their eyes. These are served on small plates and consumed with the aid of small chopsticks which are manipulated with remarkable dexterity. One particular dish which I saw looked very appetizing; this was a small omelette, inside which the cook placed two or three shrimps, tender bean sprouts and two or three other substances I could not recognise.

A Chinese food stall near the old market on boulevard Charner (now Nguyễn Huệ boulevard)

I was particularly interested to see an old woman making pancakes; instead of using a skillet, she took hold of a piece of stiff dough with two small wooden chopsticks and then held it above her stove. At every moment it seemed that the dough, sometimes swollen and sometimes stretched beyond measure, would fall into the fire; but not at all, she handled those small chopsticks with such skill that the pancake was cooked perfectly, with a delicious golden yellow appearance.

In the evening, the market is surrounded by open tables topped with Chinese lanterns which spill out onto the sidewalks. It is here that jolly feasts take place where Annamite people, essentially following their mouths, have a field day. This is a very funny show and I attended frequently. One never sees arguments, all we hear is laughter.

Leaving the market through the front door, we note the Malabar moneychangers squatting on their heels behind stacks of piastres, rupees and sapeks. The latter is the metal Annamite coin; it is made from zinc with a hole in the centre so that bunches of coins can be strung together. It takes 600 sapeks to make a ligature, which is equivalent to 0.80 Francs.

We continue our journey along the quayside, passing on our left the beautiful three-storey building constructed by a rich Chinese named Wang-Taï, and currently occupied by the Administration of Indirect Contributions.

Riverside cafes on the quai du Commerce (now Tôn Đức Thắng street)

Then we pass a row of riverside cafés, which are arranged just like their European counterparts. Here we may see young ladies of dubious virtue – many of whom came to Saigon with visiting French theatre groups and decided to stay on – serving beers and vermouths to their customers.

Nearby are the facilities of the Messageries fluviales, which has a fleet of steam ships of all sizes, perfectly fitted for hot countries. These ships transport passengers and goods to Tonkin, Cambodia and all intermediate stations. Still following the river, one reaches the Port Directorate, opposite which is moored an old demasted vessel known as the Tilsit, which is used as a pontoon and barracks for sailors; then come the Naval Stores, the Artillery and the Arsenal with its floating dock, where steamships are repaired and small boats built. The Arsenal, which occupies an area of 22 hectares, has not, for the moment, the importance it might have. In future it will become necessary to construct dry docks and provide this installation with all other necessary equipment to repair and maintain a powerful fleet. The recent events in Tonkin probably oblige the Government of the mother country to realise this project which has been studied for so long.

Travelling up the boulevard de la Citadelle, we pass the Sainte-Enfance, which receives orphans and children abandoned by their parents; the Collège d’Adran, run by the Christian Brothers; the St Joseph’s Seminary, led by priests of the Paris Foreign Mission Society; the Carmelite Convent, occupied by unfortunate nuns who it seems came to this deadly climate looking to intensify their already harsh discipline; and finally the Zoological Gardens, facing the arroyo de l’Avalanche [Thị Nghè creek].

The Zoological and Botanical Gardens

This wonderful garden, where all the useful plants of Lower Cochinchina and neighbouring countries are gathered along with the main wildlife specimens living in the colony, was established and organised by M. Pierre, a native of La Réunion endowed with an undeniable zeal and dedication to science.

All to which art and good taste can give birth with limited resources has been created in this garden, which on weekdays is the popular rendezvous of the Saïgonnais. It its elegant birdhouses we may see most of the bird species indigenous to Cochinchina, including cranes, marabous, peacocks, vultures, pheasants and swamp hens. Nearby is the monkey palace, which contains a young chimpanzee with a frightening resemblance to a human; and further along, cages containing tigers, jaguars, bears and snakes. In the parks, deer roam freely. Pelicans and other waterfowl swim on miniature lakes. On the south bank of the arroyo de l’Avalanche, a large area has been set aside for visitors to enjoy this beautiful river, covered with Chinese bridges and traversed by junks and sampans.

Leaving the Zoological Gardens, we pass on our right the Naval Stores and arrive, via the rue Tabert, at the Citadel. It has the shape of a square, each angle of which terminates in a pentagon. Its parapets are surrounded by a broad ditch without water. It is, in fact, a rather formidable fortress.

The Marine Infantry Barracks, built on the site of the 1837 Citadel in 1870-1872

It was built in 1790 by French officers during the reign of Emperor Gia Long [this is incorrect; the Citadel occupied by the French was built in 1837 during the reign of Minh Mạng to replace the larger 1790 citadel]. Within the walled enclosure we built a magnificent Marine Infantry Barracks of iron and brick, where our soldiers may find the comfortable and hygienic conditions which are so necessary for Europeans in these hot and humid regions. They are housed in superior buildings and very well nourished. We must offer the military genius responsible for these barracks the fair praise he deserves for having designed buildings which are so well adapted to the needs of the climate.

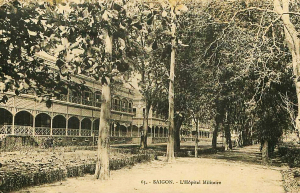

Continuing along the rue Tabert, we arrive at the Military Hospital, also worthy of the admiration of foreigners. It strikes the eye with its beautiful proportions and the perfect intelligence that governs the distribution of all the parts that make up the whole. More praise to the officers of Marine Engineering Corps!

One is particularly inspired by its beneficial system of separate pavilions, which were built, like the Marine Infantry Barracks, of iron and brick. The Military Hospital extends over a wide area and includes all the facilities that we are accustomed to seeing in larger French establishments of the same kind. Absolutely nothing has been neglected, so that our soldiers and our sailors may enjoy the best possible conditions to speed their return to health.

The Military Hospital, today a Children’s Hospital

I made a long visit to the sisters of the Hospital, with whom I was destined to stay for some time. In the parlour that serves as their living room, I met Mother Superior Benjamin, who did not seem to feel the fatigue of her 20 years of Cochinchina, along with five or six other sisters who welcomed me with affability and motherly kindness. I was moved to tears; I felt that I had found a family. When illness descends upon you, as happens so often in our unhealthy colonies, especially in Cochinchina, you are always assured of meeting with these excellent creatures, who not only provide constant and delicate care, but also to offer the consolation which only women know how to give.

Let me mention above all Sister Germaine, the nun responsible for the officers ward, all for the good, I think! It was providential that she entered the Military Hospital, for never has the Christian religion produced a more accomplished woman. Her face of angelic sweetness and her inexhaustible goodness have made her extremely popular in Cochinchina. Her name is pronounced with respect and tenderness by many officers who have received her care, and not one of her former patients will pass through Saigon without visiting this holy woman and giving her a little present.

I also visited Father Thinselin, the hospital chaplain, who combined the size of a battleship and the beard of a sapper with a face of a childish sweetness. This colossus was a true friend of his patients and all those who attended the hospital.

The Cercle des Officiers, now the District 1 People’s Committee building

On leaving the hospital, we travelled along boulevard Norodom, a wide and busy thoroughfare which is home to the Hôtel du Général, the Cercle des Officiers, the Cathedral, and right at the other end, the Palace of the Governor.

The Cercle des Officiers is a large two-storey building which owes its existence to the munificence of a Governor, who had it built in order to create a meeting place for officers of all arms. The ground floor is devoted to the marine infantry officers’ mess. On the upper floor there is a library, a reading room, a billiard room and a bar. The subscription is one piastre per month.

Close to the Cercle is a rather ugly bandstand, in which a military band plays twice a week. On those days, all the elegant people of Saigon love to promenade along this boulevard. They travel in carriages, they walk, they engage in conversation, they laugh. One could believe oneself to be in any of those cities of France where military music always draws crowds of people.

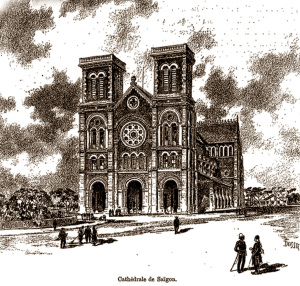

The Cathedral, which faces the rue Catinat, is far from being a pretty monument. Built entirely of brick, its great mass sitting on granite bedrock, it recalls one of those heavy pastries that are commonly referred to as pâtés. This pretentious and ugly building cost the colony several million.

The Saigon Cathedral before spires were added in 1897

Externally, it has the shape of a long rectangle bounded by two square towers and a portal. Inside, the nave is wide and very hot, since fresh air does not penetrate; it is almost like entering a diving bell. Instead of a light, elegant church with a double gallery to permit air to circulate freely, they constructed a large building without taste and without style, far too big for the small number of faithful who attend mass. It seems that they wanted to capture the imagination of the Annamites with the imposing spectacle of a grandiose church building dedicated to the Christian God; I do not know if they succeeded. But in my opinion, the design of this church is lacking.

The Palace of the Government, on the contrary, is a monument worthy of the capital of our future colonial empire in the Far East. It strikes the eye with its purity and the simplicity of its lines, as well as the beautiful proportions of its architectural mass. It quite reminds one of the Palais de Florence with its white colonnades. Located at the end of a beautiful park, the dark green colour of which highlights the whiteness of the marble facade, the palace may be seen from afar.

The two most noteworthy parts are the vestibule and the events hall, which are in no way inferior in their richness and ornamentation to any of those that we admire in our most famous Parisian palaces.

The vestibule, which is accessed by a grand marble staircase, is circular in shape, decorated with a profusion of tropical flowers and plants.

The Palace of the Government

The events hall, which can hold up to 800 people, has a grand appearance. Its rich ceiling, consisting of boxes with gilded mouldings, is supported by columns of the finest style; on each side are galleries which allow air to circulate throughout, and at the end a rotunda balcony which overlooks the park. When the room is lit and decorated for a reception or a great ball, we can see nothing more beautiful and more imposing.

Behind the palace is the Jardin de ville (City Park), a huge park of virgin forest which becomes very busy on Sundays at the time of “la Musique” [a Sunday afternoon military band concert].

On days such as this, the Jardin de ville becomes the “Bois de Boulogne of Saigon.” Between 5pm and 6pm, the carriages are so numerous that they have to file in two rows, at walking pace. This is the rendezvous of all of Saigon’s belle société, a veritable assault of fashion and elegance. Among the crowd are the pretty Congaïs, wearing rich silk clothing. We can get a good idea of the elite crowd which attends “la Musique,” a weekly promenade which has now become a regular event in the lives of the population.

The Collège Chasseloup-Laubat, now Lê Quý Đôn High School

Leaving the gardens of the Palace of the Government, we continue up to the rue Chasseloup-Laubat where the College of the same name is situated. This institution receives young Annamites from good families who are taught the French language and elements of our science and our arts. They are intended primarily for careers as government interpreters. There is also, on the rue d’Espagne, a secular school for the children of Europeans, and on the rue Nationale, a school run by the priest of Saigon where indigenous and mixed-race children are taught.

Now let’s conclude our journey of exploration through the city by travelling down the rue Catinat, the busiest and most hectic street in Saigon.

It is in this street that we find most of the public institutions: the Treasury, the Post and Telegraph Office, and the Department of the Interior, along with the residence of its Director; these latter two monuments are veritable palaces. Further down, we find the Hôtel Favre, which I have already mentioned, the Hôtel de Ville (Town Hall), which has no special character, the Theatre, and then several cafés, Chinese and European stores and clubs. The street is filled with horse-drawn carriages of all descriptions, Annamite rickshaws, and both Chinese and Annamite pedestrians who circulate all day long in crowds, producing scenes of great animation.

A Malabar carriage on rue Catinat (modern Đờng Khởi street)

The rue Nationale, which follows rue Tabert and boulevard Norodom, is also full of noise and movement. Other areas of the city have little which is worth mentioning.

Private houses are nearly all built on the Bourbon model, either of brick or wood. They are rarely more than two storeys in height and are usually composed of a main building with a courtyard and garden, decorated with a verandah in front and behind. Usually buried in the midst of a clump of greenery, they have a graceful and stylish appearance, with large and airy interior rooms. Down towards the lower part of the city, there are many houses built of brick in the European style, which serve both as shops and as housing to the traders.

The city’s drainage system leaves nothing to be desired; it is so comprehensive and well-designed that the torrents of water which inevitably follow the storms of the rainy season seem to vanish in just a few hours.

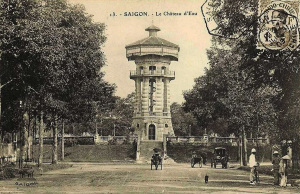

The supply of water in homes and on street corners, where good fountains and pumps are located, is provided by an elegant Chateau d’eau (water tower), built at the top of the rue Catinat extension. Abundant groundwater which has been percolated through the sands of the Plain of Tombs is brought together in a vast underground aquifer. From there, a powerful steam pumping apparatus conducts the water to the top of the water tower, whence it is distributed to different parts of the city.

The Water Tower which stood on the modern Turtle Lake intersection until 1918

Outside the boulevards, the public gardens, the squares and the parks that I mentioned, there are still, in the vicinity of the city, some charming promenades which are well frequented by city dwellers in the evenings after sunset: these are the Tour de l’Inspection and the Route de Cholon.

The Tour de l’Inspection involves a tour of the city. It leads you along a wide and well-maintained road, lined with trees, past beautiful houses, cultivated fields to the Inspection de Gia-Dinh, the residence of an Inspector of Native Affairs and an important centre of population.

There’s nothing as graceful as this small town, which quite reminds one of a clean and well-maintained European village. All the carriages stop here, then they resume their journey and pass through villages, rice fields and bridges over the arroyos.

In the summer months, from 5pm to 10pm, this route is crowded with horse-drawn carriages, which pass each other and weave their way through crowds of walkers who lazily and blissfully enjoy the fresh air.

The Pigneaux de Behaine Mausoleum (demolished in 1985)

A little further on, located in a very picturesque spot, is the tomb of the Bishop of Adran, M. Pigneaux de Behaine, who died in 1779. The Bishop, who played a major role in the last century during the reign of King Gia Long, was buried here under the care of his royal friend. After giving him a magnificent funeral, the king built this beautiful monument of Annamite art.

The road to Go-Vap, which passes through some of the best-cultivated and richest areas around the city, is another well-frequented promenade. It’s here that one can see those little Annamite houses on plots of one hectare surrounded by trees where they cultivate tobacco, corn and sugar cane. They bring to mind those fragmented farms in some parts of the French countryside which are equally well cared for by our farmers.

The two roads which lead to Cholon, 5 or 6 kilometres west of Saigon, are also a favourite promenade for carriages. The first, which is accessed from the upper part of the city, is the route Stratégique; it is wide, comfortable and the more attractive of the two. The countryside along this route is beautiful and well cultivated; Annamites of high class live in small and pretty domains, where their houses disappear amidst a tangle of mango, banana and areca nut trees.

A Saigon-Mỹ Tho train calling at Chợ Lớn station

A short distance from the city, there is a model farm known as the Ferme des Mares, where we are carrying out research into the cultivation of cane, indigo and coffee, which to date have not given very brilliant practical results.

The second road to Cholon runs along the entire length of the arroyo de Chinois; it passes through several Annamite villages which teem with a very dense population, and leads to the Hôpital indigène de Cho-Quan (Cho-Quan Indigenous People’s Hospital), which receives Annamites and Chinese of the poor class.

Those who have no carriage can reach Cholon in only 20 minutes by taking the steam tram that leaves from the bottom of the arroyo Chinois, or the newly-built railway which now goes all the way to Mytho.

After visiting the city of Saigon in all its details, I went to see Cholon, a city of 50,000 souls, exclusively inhabited by Chinese and Annamites. This is the most commercial city of Cochinchina, a great marketplace for rice, silks and teas. I arrived at 9am on a day of great celebration and went directly to the Inspection, where I received hospitality. Outside was a procession preceded by musicians beating tom-toms, clashing cymbals and playing horribly piercing flutes. It was abominable, discordant music, without rhythm and without musical theme. All one could hear was the piercing noise.

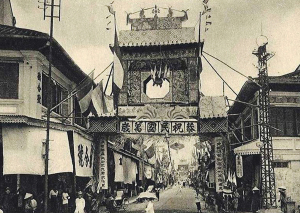

Rue de Canton (now Triệu Quang Phục street) in Chợ Lớn

After the orchestra came a group of little girls aged 6 to 7 years, adorned with magnificent costumes, their faces heavily made up, mounted on richly decorated platforms raised aloft by pages in bizarre and colourful outfits.

Other small girls were grouped together on floats, sitting in front of tables laden with dishes or doing various small handicrafts. Behind them walked guards carrying fantastic weapons and wearing brilliant costumes; others held banners, parasols and huge fans. Then came the penitents, monks in saffron robes, followed by the literati, venerable old scholars in glasses. And finally the procession of the dragon. The parade lasted half an hour. To close the ceremony with dignity, firecrackers were exploded in profusion. The whole thing was very original, but it would have been necessary to stand next to an interpreter in order to grasp the real meaning of the procession, which for us seemed more like a mascarade than a religious festival.

The city of Cholon is very much a Chinese city; it is devoted exclusively to trade, and the streets near the arroyo Chinois, covered with many high bridges, are full of shops that sell all kinds of special food for Chinese and Annamite consumption.

Chinese duck merchants in Chợ Lớn

Traders from the Celestial Empire, naked to the waist, with plump bellies and noses adorned with large spectacles, sit in front of their shops taking care of business. The accountants among them move their nimble fingers across their abacus, with which they perform the most complicated calculations.

Through a nearby doorway, I saw a Chinese schoolteacher surrounded by a gang of mischievous kids who were making a thousand efforts to appear attentive to their lesson. Further along the arroyo I passed several large rice husking factories, owned by French businessmen but run in collaboration with the Chinese.

I briefly entered the Central Market, which sold the most varied products ranging from fish and rice to clothes, shoes, books, mirrors and fabrics of all kinds.

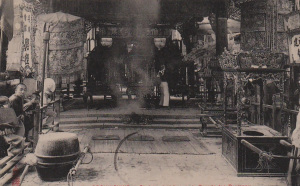

My curiosity was aroused when I saw a Chinese pagoda surrounded by a dense crowd of people. I entered and found its main hall packed with a mob whose gaiety seemed decidedly out of keeping with the respect due to a place of worship. Cake and sweet sellers had set up stalls here, surrounded by eager customers. The ceiling in this hall was decorated with a multitude of gaudy lanterns of the worst possible taste; were these votive lanterns, or had they been installed just for the festival?

The interior of a Chinese temple in Chợ Lớn

Leaving this noisy room, I entered the main sanctuary of the temple. At the entrance was the horse of the Buddha, which resembled a harmless quadruped, its attitude recalling nothing of its divine role in Chinese religion. At the rear of the sanctuary were shrines decorated with statues, candles and sacred urns. A priest looked at me good-naturedly and seemed not the least bit scandalised by my mocking smile which was inspired by the sight of the big-bellied Buddha, enthroned amidst the lesser gods that surrounded him.

An old woman kneeling on the steps of the shrine burned josticks before the images of her gods and made an offering to the priest, who responded by turning his prayer wheel at the feet of the divinity, thereby taking care of her wishes. Such a simple and uncomplicated system! However, the crowd seemed to delight more in the first enclosure than in the sanctuary, as the few devotees in the latter appeared to have a distracted air and soon rushed back to the noisy party to see what would happen next.

In the afternoon, a carriage drove me to the Cay-Mai ceramics factory, located next to a military barracks of the same name [the former Cây Mai Pagoda] occupied by a company of marines. To get there, we crossed an area of barren land scattered with Annamite mounds and tombs resembling headless sphinxes.

![L0055713 Cochin China [Vietnam].](http://www.historicvietnam.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/8641155529_73c760cd0a_o-300x184.jpg)

The Plain of Tombs

The Cay-Mai ceramics factory consists of a long low shed covered with a roof of reeds and a brick oven. The Chinese workers here artistically manipulate the clay that is drawn from the soil and give it a variety of forms according to their own imagination or the needs of their customers. In general, the objects produced by this factory – mainly vases and household utensils – are of rather coarse quality. However, some of the Cay-Mai ceramic artists are endowed with a greater ability and create groups of figures or plates and vases decorated with crabs or fish that do not lack character. What a surprise it was to see how, with such rudimentary means, they were able to make relatively fine objects.

Above the main workshop area I saw a balcony containing the modest bunk beds used by the workers of the factory. Nothing can give a better idea of the minimal requirements of the Chinese worker. He works hard and never complains; he also saves hard and contents himself with the bare essentials of clothing, food and housing. Despite this, he always seems happy and contented.

The “High Road” which led from Saigon to Chợ Lớn

How different he is to the workers of our major cities, who are in general so exacting and so unscrupulous! It seems that the Chinese, who we so often treat like an old and corrupt race of barbarians, have long since solved the social problems that we have pursued in vain for so many years. When we know better the manners and habits of this people, we will, no doubt, draw from them lessons in wisdom, moderation and social organisation.

I returned to Saigon by carriage along the road through Choquan. As I left Cholon, I was pleasantly surprised by the sight of many wonderful vegetable gardens, cultivated with talent and expertise by Chinese gardeners, where delicious vegetables such as lettuce, cabbage and asparagus are grown largely for the Saigon market.

However, since time immemorial, these people have used human manure to fertilise their crops, a

scarcely aromatic treatment which has the serious drawback of spreading intestinal worms, whose eggs are well spread over the vegetables we eat.

I stop for a moment to shake hands with the Navy doctor who heads the Choquan Hospital, and then head back to Saigon, delighted with my journey and all of the interesting things I have seen.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.