Canal construction in colonial Cochinchina

This article was published previously in Saigoneer

Commissioned in 1862 to facilitate French gunboat access around north and west Saigon, the Belt Canal was never completely navigable.

For more than a decade after the French conquest, the possibility of a major offensive by armies of the Nguyễn court in Huế remained a constant threat to the French authorities in Saigon.

A French gunboat

It was against this background in 1862 that the Cochinchina government drew up plans to dig a new Belt Canal (canal de Ceinture) linking the Lò Gốm creek in Chợ Lớn with the arroyo de l’Avalanche (Thị Nghè creek) in northern Saigon, thereby turning Saigon into an “island fortress” which could easily be patrolled by its gunboats.

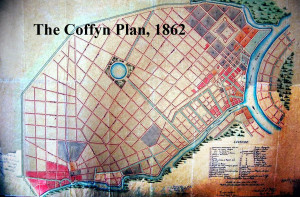

The idea of a Belt Canal was first elaborated in the abortive “Coffyn Plan” of May 1862, drawn up by Lieutenant Colonel Paul Coffyn, head of the Marine Engineering Corps Roads and Bridges Department, which sought to integrate Saigon and Chợ Lớn into a new “city of 500,000 souls,” designed in accordance with French specifications.

The Belt Canal was envisaged in the “Coffyn Plan” as part of a city-wide waterway network, based on Saigon’s existing inner-city canals and creeks (see The Lost Inner-City Waterways of Saigon and Cho Lon – Part 1: Saigon) and draining into a large central lake, which some scholars claim was a water management tool designed to tackle the problems of flooding.

The “Coffyn Plan” of 1862

However, for financial reasons, Coffyn’s grandiose vision was only partially realised. Hygiene subsequently demanded that the inner-city canals and creeks were filled from an early date, and the construction of a central lake was ultimately abandoned, along with whatever plans the French authorities had envisaged for flood control.

The only major elements of the 1862 Coffyn Plan to be implemented were the new road layout and the construction of the Belt Canal for use by French naval patrol vessels.

Both Paulin Vial (Les Premières années de la Cochinchine, colonie française, 1874) and Alfred Schreiner (Abrégé de l’histoire d’Annam, 1906) tell us that construction of the 6km Belt Canal began in November 1862, and that some 40,000 workers were recruited to dig the canal and at the same time build an adjacent defensive wall using the displaced earth.

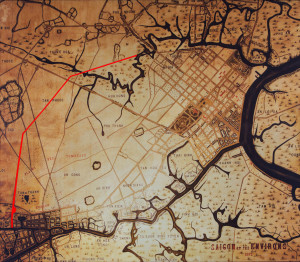

The Belt Canal is marked in red on this 1892 Saigon map on the wall of the City Post Office

All of this work seems to have been complete by the time Captain M. Bigrel drew up the Carte Générale de la Cochinchine, Canton de Dương Hòa Trung 1872-1873 for Admiral Governor V. Dupré, “thus transforming the combined cities of Saigon and Cholon into an island of nearly 20 kilometres circumference” (Schreiner).

Although the Belt Canal was essentially new build, it seems that some existing waterways may have been repurposed to create it. For example, we know that as early as 1798, materials for repairing the Giác Lâm Pagoda had been conveyed from Chợ Lớn along a creek which resembled closely the lower section of the later Belt Canal. The temporary woodshed set up at at Hố Đất wharf next to this creek to store wood, brick and stone for the refurbishment was later transformed into the Giác Viên Pagoda, now at 161/35/20 Lạc Long Quân, Phường 3, Quận 11.

According to the Cochinchina government’s Notice historique, administrative et politique sur la ville de Saïgon (1917): “It was Admiral Bonard… who began the digging of the Belt Canal, which, however, was never completed.” Several scholars, including Saigon historian Vương Hồng Sển, cite this comment as evidence that the canal was never fully dug. However, numerous late 19th century maps – most notably the 1892 map of Saigon on the wall of the City Post Office – suggest otherwise.

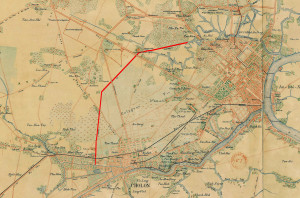

The Belt Canal is also marked in red on this Saigon map of 1895

A more likely explanation is that, while the canal had been fully dug by the early 1870s, an imbalance of water levels precluded a continuous flow along its course. This is suggested by Schreiner’s comment that work on the Belt Canal “went ahead without prior levelling, and in the absence of a serious study of the water regime, so that it could never be used as planned.” As such, it may well have been completed and even partially navigable, but sections of it remained without water and French patrol vessels were thus never able to use it to travel all the way from the Lò Gốm to the Thị Nghè.

In any case, by the 1870s the threat of landward attack on Saigon had diminished considerably and there was no longer a need for a “fortress Saigon” surrounded by waterways, neither was there any reason for commercial traffic to use this partially functioning canal located in what was then a very remote part of the city. The almost total lack of information regarding its subsequent usage suggests that by the early 20th century the Belt Canal had simply been abandoned.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.