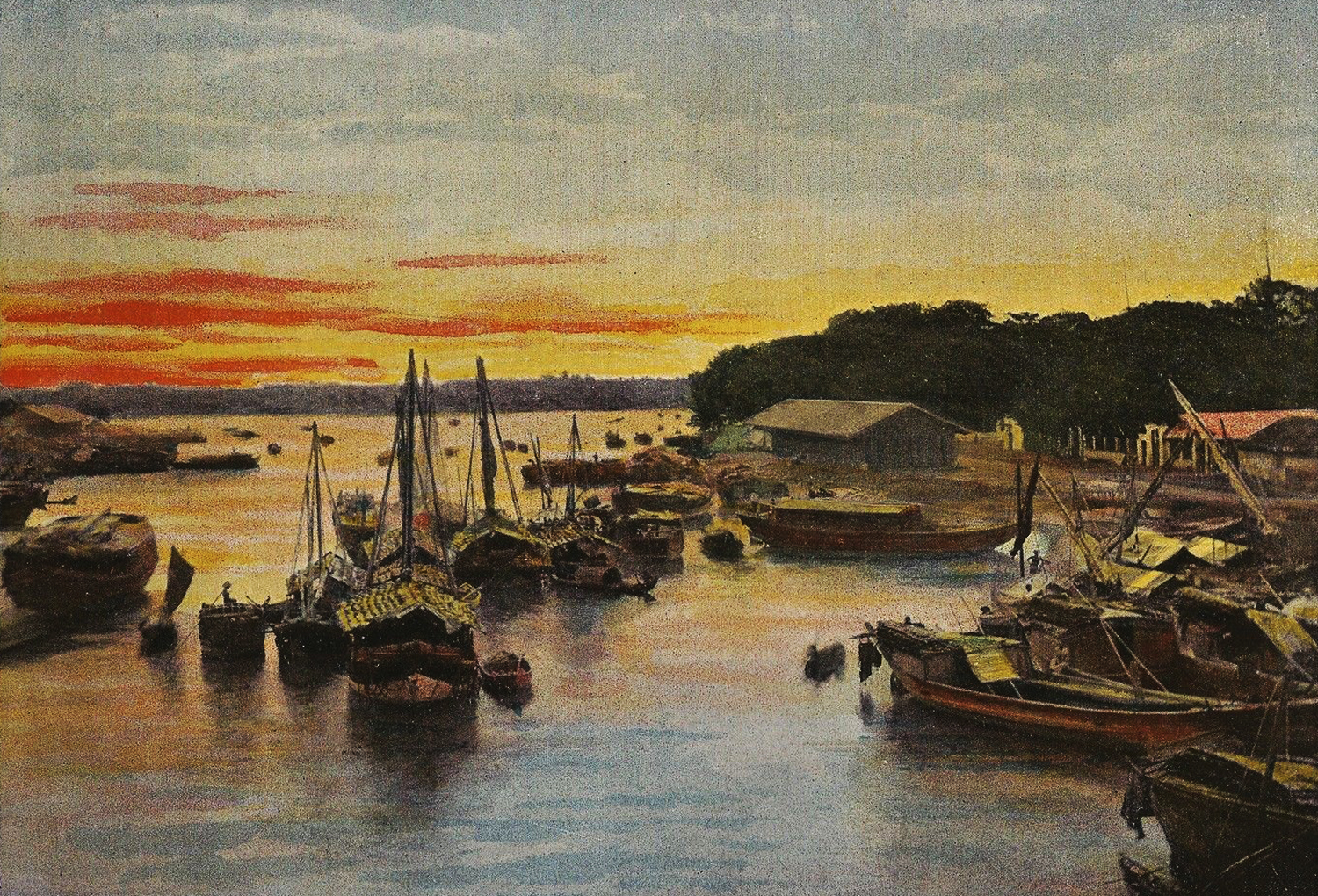

Cochinchine – the arroyo Chinois in Saïgon by Gillot

Journalist and travel writer Eugène-Claude Lagrillière-Beauclerc visited Cochinchina in 1899. Here is his description of Saigon and Chợ Lớn, published in Voyages pittoresques à travers le monde: de Marseille aux frontières de Chine (1900).

Since seven this morning, we have been following the coasts of the Poulo-Condor islands, a place of exile for the condemned of Indochina. The pitching motion has subsided. The sea still swells a little, but we manage to run at 14 knots per hour.

Cap Saint-Jacques beach – fishermen

Tonight we will be in view of cap Saint-Jacques, at the entrance of the Saigon River, and by two in the morning we will be in Saigon. Tomorrow, out of the 750 passengers who boarded the ship in Marseille, only 10 will remain on board; all of the military will get off and head for Tonkin, while most officials and traders will stop in Cochinchina.

At 10am on 10 February, after four hours of navigation along the branch of the river leading from cap Saint-Jacques to Saïgon, we approach the wharf of the Messageries maritimes.

Saigon has 20,000 inhabitants, of which around 2,000 are Europeans. The city is also home to more than 10,000 Chinese; Annamites [Vietnamese] come barely third out of the total number of the population.

A sampan at the wharf of the Compagnie des Messageries maritimes

What strikes us when landing is the modern aspect of this city; the streets are wide and lined with beautiful sidewalks. Plantations of trees in dense foliage pleasantly shade the main avenues. It is a curious thing, this motley population made up of Europeans, Chinese, Annamites and foreigners from all over the world, flowing through the streets of this city of the Far East, the general character of which reveals the imprint of the most modern Western civilisation.

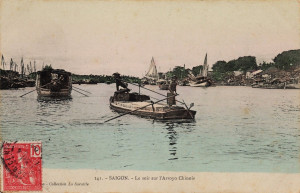

In the harbour, we see ships from all nations. These are mostly commercial vessels, the inscriptions on which reveal their places of origin: Marseille, Dunkirk, Le Havre, Singapore, Bombay, Haïphong, Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Manila, Yokohama. It seems that this part of the Far East is a meeting place for all the peoples of the world.

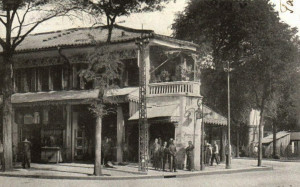

The Grand-Hôtel Continental in 1902

Monsieur Boniface Bollard tells me that he plans to stay at the Grand-Hôtel de Saïgon [the Continental Hotel], opposite the Theatre. I have no preference, so of course, I decide to take a room in the same hotel, in order to stay in the company of our scientist, whose jovial character and profound erudition I greatly appreciate.

My room is large and airy, but furnished in a rather crude manner.

The bed, comprising a mattress with the thickness of a doormat, is surrounded by a rectangular framed gauze veil: it’s the mosquito net, protective shell, beneficent guardian of sleep for every human being in the intertropical regions. Two rattan chairs, a dresser with drawers which have long refused to open and which persist in their resistance to any effort, an en-suite shower room which also serves as a toilet… that’s what the furnishing looks like in one of Saigon’s premier hotels.

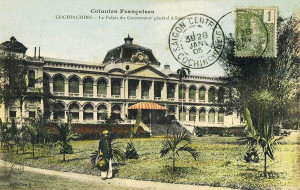

The Palace of the Government, Saigon

Detail to mention: there is no fireplace in the rooms, and this is easily explained. Throughout the whole extent of Cochinchina, it is never necessary to heat rooms. The thermometer rarely dips below 16° centigrade. During the normal season, the temperature oscillates between 20° and 30°, going up to 36° or 37° in May and June, the hottest days of the year.

After unpacking a few possessions – my stay will be short-lived, because my desire is to travel for a few days in Cambodia – I decide to go and present my respects to the Governor-General of Indochina, whom I had met some months before in Paris, in the cabinet of the Minister of Colonies.

MD, apprised of the study mission with which I have been charged by the government, invites me to lunch and offers me excellent advice on how I should plan my journey.

A festival day in Saigon at the turn of the century

He urges me to go first to Cambodia, then to descend into Cochinchina. After that, I must go up to Annam and Tonkin.

This is the programme which I will follow, and as it happens, this route corresponds closely with the one proposed by M. Bollard, who also attends the luncheon with the Governor-General. I have the deep satisfaction to learn that, over a period of several long months, I’ll have for a companion the most jolly man in France – and one of the most learned.

During these three days it is the festival of Tet, the Annamite New Year.

Outside the houses, masts have been installed, each with betel, areca and lime attached at the top. These are offerings to the air spirits and ancestors. My friend Bollard, who knows everything, gave me the following information:

Many religious systems are practised in Indochina.

Saigon – evening on the arroyo Chinois

There is Buddhism, the doctrine of Confucius, ancestor worship, and the worship of genies and spirits.

The Catholic missions have also implanted Christianity in these regions, and currently the proportion of Catholics is 1 out of 28. Brahmanism, very widespread in India, is becoming increasingly rare in Cochinchina, although some monks from the coasts of Coromandel strive to keep adherents to the Hindu trinity.

By adding a few Muslims, followers of Muhammad’s son-in-law Ali, one has more or less accounted for all of the religious varieties of Indochina.

However, amongst the Annamite people, the two cults practiced above all others are those of the ancestors and the genies.

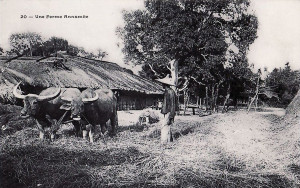

A Vietnamese farm

By hooking betel quid to the top of those masts for the genies and spirits, popular naivety believes that it is possible to ward off bad luck.

In the mind of the natives, the spirits from beyond the grave seize every being who is born, and thus begins the fight between good and evil.

Ancestor worship is intended to obtain protection from the forbears against evil spirits. This cult is the natural continuation of the morality practiced in life by the Annamite people. They have deep respect for the family.

Walking through the streets of Saigon, we are greeted on every sidewalk by firecrackers, and the explosions follow one another in quick succession.

A Chinese restaurant in Saigon

Curiously, the streets are almost deserted. The Malabar carriages no longer run, because the Annamite drivers have been released for the holiday; commercial life is suspended, except in the taverns, where they play a game of chance called bacouan, which is permitted only at this time of year.

This game is very simple, and a few lines of description may help you understand it.

Around the table sit Chinese and Annamites, sometimes also Europeans. On the table is a square tablet, with the numbers 1 to 4 at its corners. Each player chooses a number and covers it with the money he wants to risk. But number four remains uncovered. It belongs to the croupier. The latter, always a Chinese who has paid the establishment for the right to hold the game, shakes in front of everyone a bag of sapèques (small zinc coins with a hole in the middle), and then reaches into the bag and removes a handful of these metal washers. He counts the sapèques coming out of the bag in fours, and when he arrives at the last ones, there remain just one, two or three copper coins. The winner is the player whose chosen figure on the table corresponds to the number of remaining coins. The croupier has 25 chances out of 100 to win without risking anything.

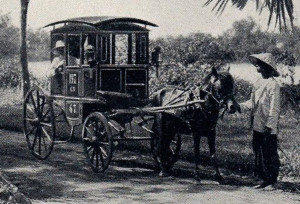

A Malabar four-wheel carriage

In fact, this game is no more immoral than roulette, and it is significantly less disadvantageous for the players than the game of ludo, where the proportion of opportunity for the croupier exceeds 60%.

We exit one of the establishments, where, for three days during the Tet holiday, they are playing bacouan without interruption for up to 72 hours. We continue our walk through the city.

Most houses are sumptuously decorated; on their facades sway huge paper lanterns.

In the interiors, incense is burned in front of the altars of the ancestors.

We are able, with difficulty, to discover a Malabar (four wheel carriage) driven by an Annamite coachman who, in less than two hours, has lost all his savings playing bacouan.

Another Malabar carriage in Saigon

Our coachman says: “I go Cholon. Chinese play bacouan here all thieves; in Cholon they better. Come, Cholon, see beautiful city.”

As Cholon merits a visit, since it is the big market and the rice warehouse of all Cochinchina, we welcome our good coachman’s offer, and at seven in the evening we are on the road from Saïgon to Cholon.

Cholon, located 5 kilometres from Saïgon, is, by the size of its population, a city more important even than the capital of Cochinchina.

It has 40,000 inhabitants, including nearly 20,000 Chinese. The rest of the population is Annamite.

In Cholon, one can get a very exact idea of what a Chinese city is like.

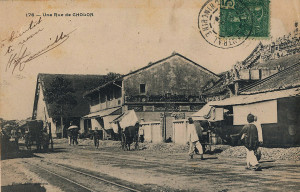

A Cholon street

Because everything is Chinese: business and residential houses, customs and mores. Upon entering the town, we find that they celebrate Tet here with as much enthusiasm as they do in Saigon. All the doors are open and the interiors of the houses are brightly lit.

The colourful images on the huge lanterns are all symbolic and express wishes. In this way, most of the designs depict plants emerging from a horizontal line, symbolising the earth. When four or five plants are juxtaposed, that means four or five generations sprouting from the same primitive soil. Translation: the one who has this symbol at the entrance to his house expresses the desire to live long and to see four or five generations grow before his eyes.

On the doorsteps, children ignite fireworks, and it is in the midst of terrible backfiring and bursts of brilliant and joyous flares that our carriage slowly advances forward through the streets of Cholon. We stop at the door of an opium den.

An opium smoker

Imagine a darkened room, around which extend a series of low cots. A dozen Chinese lie in elongated or curled attitudes. Next to each burns a small lamp filled with coconut oil. It’s over the flame of this lamp that they heat a big ball of opium, turning it on the tip of an iron needle. And from that they absorb the smoke by a single aspiration, while the opium is boiling. An opium pipe may be smoked in just two seconds. Heavy smokers may thus prepare up to a hundred pipes in an evening.

We see clients of the den. They have an air of extreme bliss, and it is while closing their eyes at length that they take deep breaths of the opium smoke.

We ask the manager of the den to prepare a pipe for us, but he refuses, smiling. It seems that this kind of exercise is prohibited by European regulations applying to public dens.

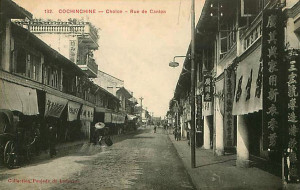

Rue de Canton, Cholon

Coming out of this cave, we resume our walk through Cholon, and the show goes on, uniform, without the least variety, from one street to another.

Everywhere the game of bacouan, everywhere fireworks, and it will last until the morning, we are told.

This Tet is the most important festival of the year, and even the poorest people like to celebrate it.

We return to the Grand-Hôtel de Saïgon and retire to our rooms, where we are quickly devoured by some creatures which have discovered how to slip through the nets which surround our beds from base to top.

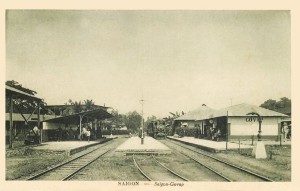

The next day, accompanied by Dr Blin, doctor of the colonies, we take the train to Govap, half an hour from Saigon. We have been told about the Pagode des présages [Pagoda of omens] in this place, a Chinese pagoda where Confucius is worshipped.

Gò Vấp Station

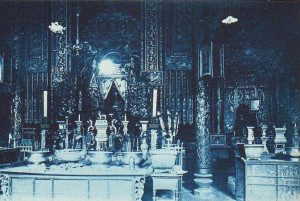

The monks welcome us in a hospitable manner, and we admire the ornamentation of the pagoda, in which there is no representation of the human figure. At the foot of the shrine, placed in saucers, all the condiments of Chinese menus are lined up in honour of deceased ancestors, who can, we are told, breath in the aromas.

They offer us a book written in Chinese. We accept gladly, relying on a friend to give us a sense of its meaning, because Chinese is as unknown to us as the Annamite language.

Hardly have we left the pagoda than the gong sounds and the lights glow in the rear hall. It appears that they are cleansing the sanctuary, the presence of a heretic making this operation essential.

The interior of a Chinese temple

We cannot but recognise the perfect courtesy of the monks, so welcoming to outsiders, whose presence in this pagoda is enough to disturb the spirits of ancestors sleeping the eternal sleep.

Leaving the pagoda at Govap, we enter some Chinese shops. In one of them, we are offered a remedy against migraine, some beer made in Saigon, cigarettes and perfumes.

The beer being execrable, we ask to taste the milk of a coconut as large as a melon, which a boy has just bought in the market.

Our Chinese guide, who speaks some French, acquiesces to our request and opens the coconut with an axe. We then pour the contents (around half a litre) into a bowl.

A coconut seller

We taste it. It’s warm, bland, slightly sweet and rather unpleasant. This kind of liquid has little chance of attracting our clientele.

To thank our Chinese guide, we buy him an almanac written in the Mandarin language, plus a card game and instructions on how to play it.

All these chinoiserie cost us 20 cents, about 0.50 francs in our French currency.

We reboard the train to Saigon. On the journey, we admire the beautiful vegetation that unfolds before our eyes.

Everywhere there are guava trees, banana trees, palm trees laden with fruit, and areca palms whose nuts sway in the slight breeze. We know that the areca nut is the basis of betel quid, which is chewed by many Annamite woman.

An areca plantation

The quid consists of a piece of areca nut and a little lime tinged in red, all wrapped in a betel leaf. Salivation produced by this chemical combination is reddish. Annamite women constantly chew betel, and their teeth gradually assume a beautiful black colour, one of the special characteristics of Indochinese dentition.

On this subject, we were told an amusing story.

Recently, a dentist in Saigon placed in his surgery window a beautiful set of false teeth, all the colour of black ink. Many Annamites stopped, ecstatic before this jewel, wondering to whom could belong these beautiful teeth blackened like Chinese ink, waxed, polished and shiny as jet.

It seems that the false teeth were commissioned by H M King Norodom of Cambodia, who had the stumps extracted from his royal mouth in order to adorn it with these thirty-two ebony gems.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.