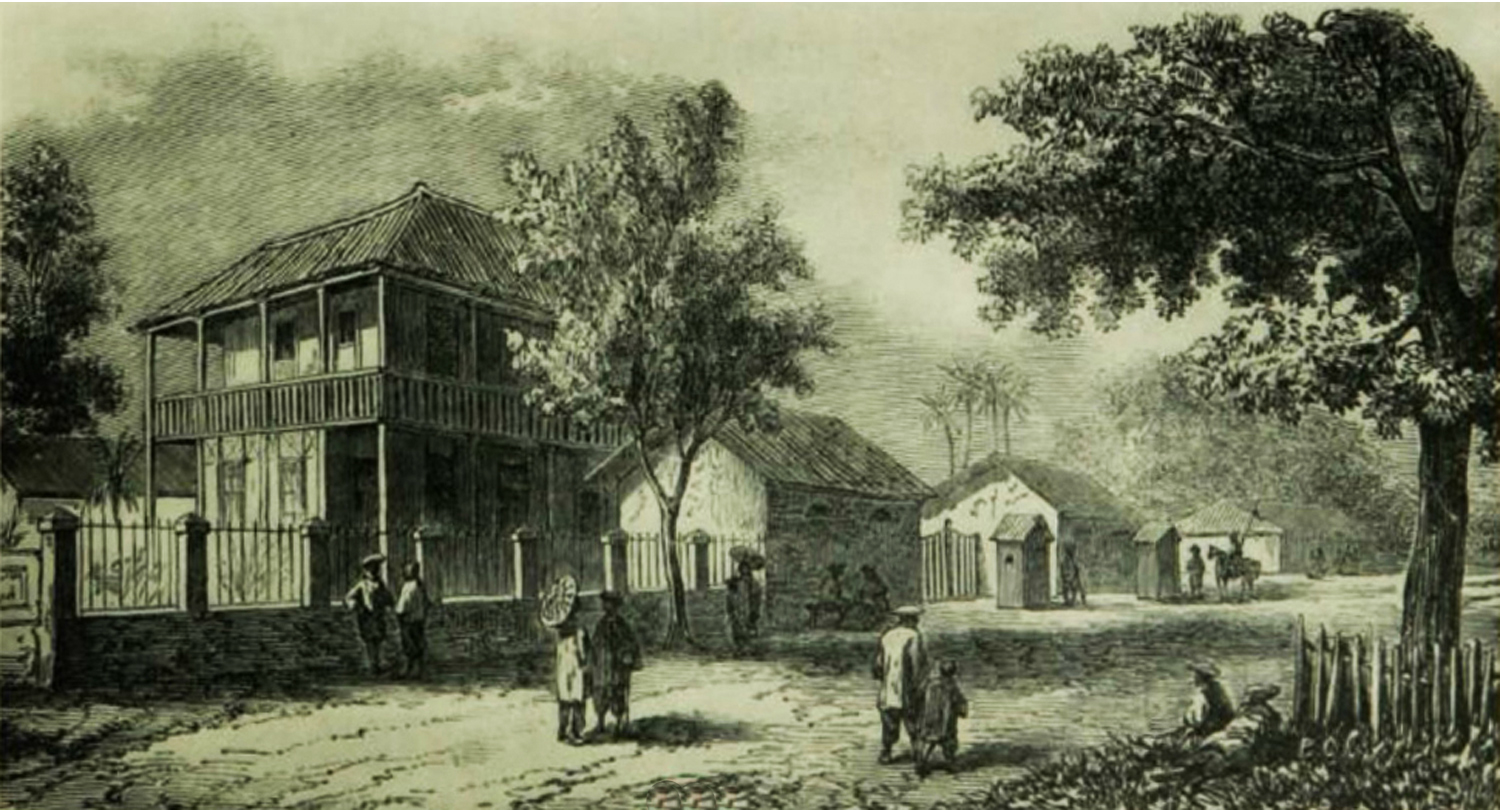

“La première résidence des Gouverneurs à Saigon” – an exterior view of the first governor’s palace, from the 1931 book Iconographie historique de l’Indochine française (1931) by Paul Boudet and André Masson

This article was published previously in Saigoneer

It’s often assumed that the Norodom Palace (1873) was the first colonial governor’s palace to be built in Saigon, but it was in fact preceded by a much humbler structure, the Hôtel des Amiraux-Gouverneurs.

For more than two years after the French conquest of Cochinchina in 1859, the early Admiral-Governors – Rigault de Genouilly, Jauréguiberry, Page and Charner – were billeted in temporary premises within the Naval Barracks next to the Saigon River.

Admiral-Governor Louis Adolphe Bonard, 28 November 1861-23 April 1863

However, when Admiral-Governor Louis Adolphe Bonard took over in November 1861, a dedicated governor’s palace was deemed a priority and the Naval Engineering Corps was charged with building one.

Unfortunately at this time funds were still limited, so it was decided to build a temporary palace which could be replaced at a later date by a more permanent structure. In December 1861, a set of wooden buildings was imported in kit form from Singapore and assembled at the top end of the rue Catinat (Đồng Khởi), next to the place de l’Horloge (Clock Square, after the clock tower which stood at its centre), an area which was already home to several other colonial government offices.

Standing on the site occupied today by the Trần Đại Nghĩa High School, this Hôtel des Amiraux-Gouverneurs incorporated a governor’s residence, offices and meeting rooms, a 600-seat salle de spectacles (events hall), a stable and a pig farm. Drawings of the building were published in the 1931 book Iconographie historique de l’Indochine française (1931) by Paul Boudet and André Masson.

Phạm Phú Thứ, 1821-1882

Diplomat Phạm Phú Thứ, who accompanied royal mandarin Phan Thanh Giản to Saigon in 1863-1864, described the building as follows:

“The Governor’s palace comprises four buildings constructed in a line, each with nine compartments and eight doors.

The central compartment of the first building forms the main entrance. The four two-storey compartments on the west side of this building are the Governor’s apartments, while the four compartments on the east side form the offices.

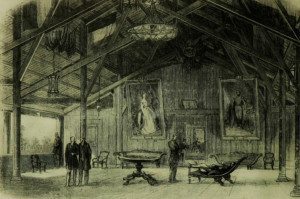

An intermediate structure connects the first building with the second building, where the reception or conference room may be found. On the west wall of this room are hung two large portraits: the one on the right is that of the Ung Ba Su (Emperor), the Head of the French State, while the other one on the left is that of Y Pha Ra Tri Xa (the Empress), the Queen. In between them is hung a small portrait of the son of the Head of the French State. On the east side, the sixth and seventh compartments form waiting rooms, while at the rear we may find the Salle de spectacles or music room.

This building, painted very beautifully, connects with the third building, where the dining room is located.”

(Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Hue, No 1-2, April-June 1919).

“La première résidence des Gouverneurs à Saigon” – portraits of the French Emperor and Empress inside the first governor’s palace, from the 1931 book Iconographie historique de l’Indochine française (1931) by Paul Boudet and André Masson

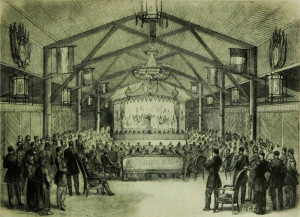

The Salle de spectacles of this first governor’s palace was used for a variety of functions, including the staging of performances by visiting theatre and music companies before the inauguration of the first Théâtre de Saïgon in 1872.

After the demolition in the early 1870s of the first wooden cathedral – the Église Sainte-Marie-Immaculée, which stood on the site of the modern Sun Wah Tower until it became infested by termites – the salle de spectacles was also pressed into service every Sunday as a makeshift church.

Despite Phạm Phú Thứ’s flattering description, the Hôtel des Amiraux-Gouverneurs was a very basic structure in a city which already had several large and impressive brick buildings. One in particular, the imposing Maison Wang-Tai on the Saigon riverfront – see Wang Tai and the Cochinchina Opium Monopoly – could be seen by everyone arriving in the city.

“La première résidence des Gouverneurs à Saigon” – the Salle de spectacles or events hall of the first governor’s palace, from the 1931 book Iconographie historique de l’Indochine française (1931) by Paul Boudet and André Masson

Indeed, it’s said to have been a source of great embarrassment to the French authorities that a Chinese businessman had such a splendid headquarters while the colonial Governor still resided in a wooden hut. That embarrassment is often advanced as a reason why so much money was spent in 1868-1873 on the spectacular new Palace of the Government (later the Norodom Palace, see Saigon’s Palais Norodom – A Palace Without Purpose), reportedly the most expensive civic building constructed in East Asia during the late 19th century.

In 1873, after the colonial Governors had moved out, the old wooden palace buildings were given to the Société des Missions Étrangères de Paris (MEP) and Father Henri de Kerlan transformed them into a school named the Institution Taberd. The new school was taken over in the late 1880s by the Christian Brothers, who in 1890 had it reconstructed as the large three-storey colonial building which today houses the Trần Đại Nghĩa High School.

Clock Square and the Telegraphic Services Office in 1862

Built in 1890 by the Christian Brothers, the Tabert School, now the Trần Đại Nghĩa High School, stands on the site of the former Hôtel des Amiraux-Gouverneurs

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.