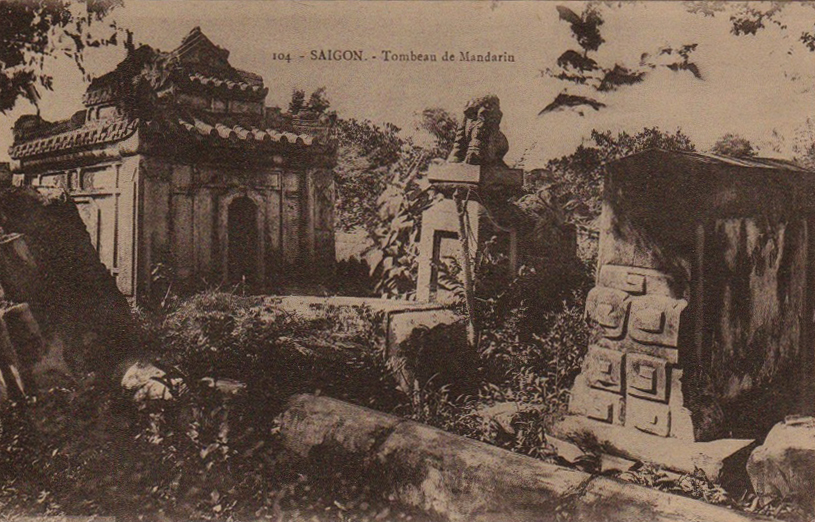

Surviving documents from the French colonial era suggest that there were once numerous Nguyễn dynasty mandarin mausoleums in Phú Nhuận

Now a bustling urban district of Hồ Chí Minh City, Phú Nhuận is said to have once been the preferred place of residence for court mandarins working at the 1790 Gia Định Citadel. Today the adventurous traveller can still find relics of that royal past hidden amidst the urban sprawl.

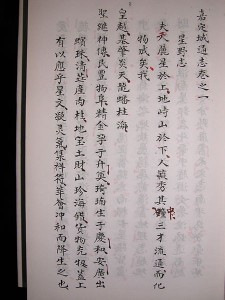

A page from Trịnh Hoài Đức’s Gia Định Chronicle

Phú Nhuận is one of several ancient villages listed in Trịnh Hoài Đức’s Gia Định Chronicle (Gia Định thành thông chí, 嘉定城通志), which was written some time before 1820. It acquired greater significance after the construction of the first Gia Định citadel in 1790, when it seems to have become home to many royal mandarins.

Many visitors and residents are familiar with the grand mausoleum of Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt (1763-1832) in Bình Thạnh district. One of the leading military strategists and commanders of Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (the future King Gia Long) in the war against the Tây Sơn, Duyệt later famously served as Viceroy of Gia Định, ruling with full power on behalf of the king over southern Việt Nam. But few people ever visit the mausoleums and tombs of other leading mandarins of that period, which may still be found scattered around the streets and back-alleys of Phú Nhuận district.

The Lê Văn Duyệt Mausoleum in Bình Thạnh district

In his long war (1774-1801) against the Tây Sơn brothers, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh turned first to Siam and later to France for military aid. Funds raised by his French ally Bishop Pigneau de Béhaine in the 1780s enabled him to purchase modern weaponry and enlist the services of French military advisers to train his troops in modern infantry tactics and the use of heavy artillery. A naval workshop was also set up in Bến Nghé (Saigon) to assemble a fleet of modern warships. In the 1790s, these military reforms enabled Ánh to launch a series of successful campaigns against Tây Sơn bases in the south-central region, paving the way for his final victory in 1801.

Yet it wasn’t all about the military hardware. A great deal of credit for the military successes of the 1790s was down to Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s military commanders, men of courage whose leadership qualities and selfless service had marked them out from an early date as trusted lieutenants. After their deaths, these men were honoured by the construction of mausoleums in Phú Nhuận district

A tiger stele guards the tomb at the Võ Tánh Mausoleum

A native of Biên Hòa who was later celebrated as one of the “Three Gia Dinh Heroes,” Võ Tánh or Võ Tính 武性 (?-1801) – whose mausoleum is at 19 Hồ Văn Huê – was rewarded in 1788 for his staunch military support with the post of Royal Envoy (Khâm sai chưởng cơ) and the hand in marriage of Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s sister, Princess Ngọc Du. In 1790, Võ Tánh led an attack on Diên Khánh in central Khánh Hòa, defeating the Tây Sơn general Đào Văn Hồ and capturing the citadel. In 1793 he was promoted to Envoy of the Palace Rear Guard, “Victory over the Tây Sơn” General and Royal Escort (Khâm sai Quán suất Hậu quân Dinh Bình Tây Tham thắng Tướng quân Hộ giá) and in 1794 he was elevated to Duke and Great General (Quận công Kiêm lãnh chức Đại Tướng quân).

The main hall of the temple at the Võ Tánh Mausoleum

In subsequent years, Võ Tánh’s military leadership contributed to a series of Nguyễn victories over the Tây Sơn, culminating in 1799 with the capture of the old Chàm citadel of Đồ Bàn near Quy Nhơn, which the Tây Sơn had occupied in 1778 and renamed the Hoàng Đế citadel. Nguyễn Phúc Ánh changed its name again, calling it the Bình Định citadel. Võ Tánh and his fellow general Ngô Tùng Châu were then placed in charge of it, while the Nguyễn army returned south to Gia Định. However, shortly afterwards a large Tây Sơn army led by generals Trần Quang Diệu and Võ Văn Dũng laid seige to the citadel for 14 months. In 1801 Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, along with commanders Lê Văn Duyệt and Võ Di Nguy, came north with a large army and won a decisive victory over the Tây Sơn fleet in the nearby Thị Nại estuary, but they failed to raise the seige of Bình Định.

An exterior shot of the temple building at the Võ Tánh Mausoleum

With the garrison facing starvation, one of Tánh’s deputies suggested that it might be a good idea to surrender or escape. “We have our orders and we’ve sworn to live or die together here,” Tánh is said to have replied defiantly. “If we abandon the citadel and flee like cowards, how can we ever face our [Nguyễn] Lord again?” After securing a promise from Tây Sơn general Trần Quang Diệu that his soldiers would be safely released, Tánh packed straw, firewood and gunpowder beneath a wooden platform, strapped himself on top and ignited it, committing suicide. Ngô Tùng Châu also killed himself by taking poison. When Trần Quang Diệu finally entered Bình Định citadel, he was said to have been so touched by the courage of the two Nguyễn generals that he spared the lives of the remaining members of the Nguyễn garrison, just as Võ Tánh had requested. Less than a year later, the Tây Sơn armies were routed and Trần Quang Diệu and Võ Văn Dũng in turn were forced to abandon the citadel.

A model ship in the temple at the Võ Di Nguy Mausoleum references the important role he played in the development of the Vietnamese navy

Some historians believe that it was the superior firepower of Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s navy which played the most decisive role in the war, and Võ Di Nguy or Vũ Di Nguy 武彝巍 (1745-1801) – whose mausoleum is at 19 Cô Giang – was the man who presided over its development.

In September 1788, after Nguyễn Phúc Ánh had recaptured Gia Định, Võ Di Nguy was placed in charge of the Chu Sư (now Ba Son) naval workshop, where he oversaw the construction of a fleet of modern warships. He went on to become one of Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s greatest admirals – in 1793, along with Nguyễn Văn Trương and Võ Tánh, Võ Di Nguy led a successful attack on Quy Nhơn and recaptured Bình Khang (now Ninh Hoà district in northern Khanh Hoa). Two years later, he and Phạm Văn Nhơn co-led a naval attack along the Cái River to Diên Khánh Citadel in central Khánh Hòa.

A decorative screen in the tomb area of the Võ Di Nguy Mausoleum

However, like his British contemporary Horatio Nelson, Nguy’s most famous naval battle – the 1801 victory over the Tây Sơn fleet in the Thị Nại Estuary – was also his last. He was killed by cannon fire on 27 February 1801.

One of Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s first acts after reunifying the country as King Gia Long was to honour both Võ Tánh and Võ Di Nguy.

Võ Tánh was initially laid to rest in a joint mausoleum with his fellow commander Ngô Tùng Châu within the grounds of the citadel they had defended so valiantly. However, they were later reburied, Ngô Tùng Châu in Phù Cát and Võ Tánh in Phú Nhuận.

The tomb at the Võ Tánh Mausoleum

According to historian Vương Hồng Sển, King Gia Long had to commission a wax effigy of Võ Tánh for the reburial ceremony, because his body had been so badly burned. Võ Tánh was posthumously honoured as a Meritorious High-Ranking Duke (Dực vận công Thần thái úy Quốc công) and in 1832 King Minh Mạng conferred on him the posthumous title Perpetual Duke (Hoài Quốc công). Together with Đỗ Thanh Nhơn and Châu Văn Tiếp, Võ Tánh is ranked as one of the Gia Định Tam Hùng (“Three Heroes of Gia Định”).

Võ Di Nguy’s body was also brought ceremoniously south to Gia Định, where he was posthumously named Hầu tước (“Marquis”) and treated to a grand state funeral before his burial in Phú Nhuận. In 1824, King Minh Mạng had a temple established in Võ Di Nguy’s honour and upgraded his posthumous title to Bình Giang Quận công (Duke of Bình Giang).

The temple viewed from the tomb area at the Trương Tấn Bửu Mausoleum

Trương Tấn Bửu 張進寶 (1752-1827) is another of the Nguyễn dynasty military commanders honoured in Phú Nhuận, whose mausoleum is at 41 Nguyễn Thị Huỳnh. A native of Vĩnh Long (now Bến Tre) province, he became Lieutenant General of the Vanguard (Tiền quân Phó tướng) in 1797 and played an important role in the final military campaigns of the 1790s. However, unlike Võ Di Nguy and Võ Tánh, he survived the Tây Sơn war to serve the new Nguyễn king.

In 1802 Bửu was appointed Lieutenant General and Head of the Palace Vanguard responsible for the Northern Citadel Army (Chưởng dinh, Quản lĩnh đạo quân Bắc Thành), in effect commander of all Nguyễn forces in northern Việt Nam. In his later years, he twice occupied the post of Deputy Governor of Gia Định Citadel as second-in-command to Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt, in 1812-1816 and again from 1821-1822.

The facade of the temple at the Trương Tấn Bửu Mausoleum

When Trương Tấn Bửu died in 1827, King Minh Mạng contributed 2,000 coins towards the cost of his funeral. Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt himself purchased the land for Bửu’s tomb and temple and personally took charge of the funeral ceremony. In 1852, King Tự Đức also installed a shrine to Trương Tấn Bửu in the Hiền Lương Temple, which had been set up in the Huế Citadel to honour heroic and meritorious royal officials. Today, Trương Tấn Bửu is still remembered as one of the “Five Tiger Generals” (Ngũ hổ tướng), along with Nguyễn Văn Trường, Nguyễn Văn Nhơn, Nguyễn Huỳnh Đức and Lê Văn Duyệt.

The mausoleums of Võ Di Nguy, Võ Tánh and Trương Tấn Bửu were built in the architectural style of the Nguyễn dynasty, with a temple in front and the tomb at the rear. All three have survived, in differing states of preservation.

The Võ Tánh Mausoleum (Lăng Võ Tánh) may be found at the end of Hẻm 19, Hồ Văn Huê street in Phú Nhuận district and comprises a temple and a tomb area set amidst well-kept gardens. In 2010-2011 the complex was extensively rebuilt using a mixture of traditional and modern construction materials, but following the original design. The front hall of the temple currently functions as a recreation space and club room for the local martial arts club. Although not yet recognised as a historic monument, it is open daily from 7am-8pm.

The use of otters in the decoration at the Võ Di Nguy Mausoleum references the legend that once, while on the run from the Tây Sơn, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh got lost in the forest and found his way back by following the footprints of an otter

The Võ Di Nguy Mausoleum (Lăng Võ Di Nguy) is located at 19 Cô Giang in Phú Nhuận district. The temple has been restored many times over the years, most recently in 1990, when it was unsympathetically rebuilt using modern construction materials. Nonetheless it still preserves its original architectural composition. The tomb section at the rear of the compound retains its original form, but is now seriously degraded and in urgent need of conservation work. Recognised as a national architectural and artistic monument in January 1993, the mausoleum is looked after by a resident family who open the doors on request from 7am-11.30am and 1.30pm-4.30pm daily.

The Trương Tấn Bửu Mausoleum (Lăng Trương Tấn Bửu) is situated at 41 Nguyễn Thị Huỳnh street in Phú Nhuận district and also functions as the home of the caretaker. During the First Indochina War, the temple became a district headquarters for anti-colonial forces and is said to have suffered serious damage during an attack by French soldiers. It was rebuilt in 1959 along with a new assembly hall which nowadays serves as the caretaker’s residence. Like that of Võ Di Nguy, the tomb area is in a very poor state of preservation, although the mausoleum was recognised as a national architectural and artistic monument in December 2004.

Surviving documents from the French colonial era suggest that there were once several other Nguyễn dynasty mandarin mausoleums in Phú Nhuận, though sadly they have long been lost to urban development. However, one other tomb has survived.

The rear face of the stele which guards the Phan Tấn Huỳnh Tomb

Though never honoured by the construction of a temple or mausoleum, Phan Tấn Huỳnh 潘晉黃 (1752-1824) distinguished himself in the service of Nguyễn Phúc Ánh during the Tây Sơn war and became a high-ranking mandarin at Gia Định Citadel after Ánh took the throne in 1802.

During the Tây Sơn war, Huỳnh is said to have fought courageously in the armies of Nguyễn Phúc Ánh under leading generals such as Lê Văn Duyệt, Ngô Tùng Châu, Võ Tánh and Trương Tấn Bửu. In 1807 he himself became a General and High-ranking Special Envoy and was charged with assisting Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt in his duties as Governor of Gia Định. According to the text written in Chinese on his tombstone, he was responsible for writing all of Lê Văn Duyệt’s official reports to the king.

This small stele is inscribed with Phan Tấn Huỳnh’s names and titles

Phan Tấn Huỳnh distinguished himself in battle again between 1809 and 1816, when he was sent north to Quảng Ngãi province to put down a major ethnic minority uprising. In 1820 he became Deputy Divisional Commander and in 1822 Divisional Commander of Phiên An (Bến Nghé). During this period he is said to have promoted the colonisation of much new land, gainng a reputation for kindness by providing free food and clothing for settlers. After 1822 Phan Tấn Huỳnh’s health began to deteriorate due to old age. By 1824 he was very infirm, so in order to avoid becoming an encumbrance to his family, he took his own life.

The Phan Tấn Huỳnh Tomb (Mộ Phan Tấn Huỳnh) may be found in Hẻm 120, Huỳnh Văn Bánh street in Phú Nhuận district, and is accessible at all hours. The small tomb compound comprises an altar in front of the tomb, backed by a small stele inscribed with Phan Tấn Huỳnh’s names and titles. Behind the tomb is a large screen inscribed with Chinese characters which tell of his distinguished career. Not yet recognised as a historic monument, the tomb is in poor condition.

You may also be interested to read these articles:

Ancient Tombs of Saigon – Phan Tan Huynh Tomb, 1824

Ancient Tombs of Saigon – Lam Tam Lang Tomb, 1841

Ta Duong Minh – Thu Duc’s Founding Father 1860s

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.

The tomb at the Võ Tánh Mausoleum

The tomb at the Võ Di Nguy Mausoleum

The tomb at the Trương Tấn Bửu Mausoleum

The Phan Tấn Huỳnh Tomb