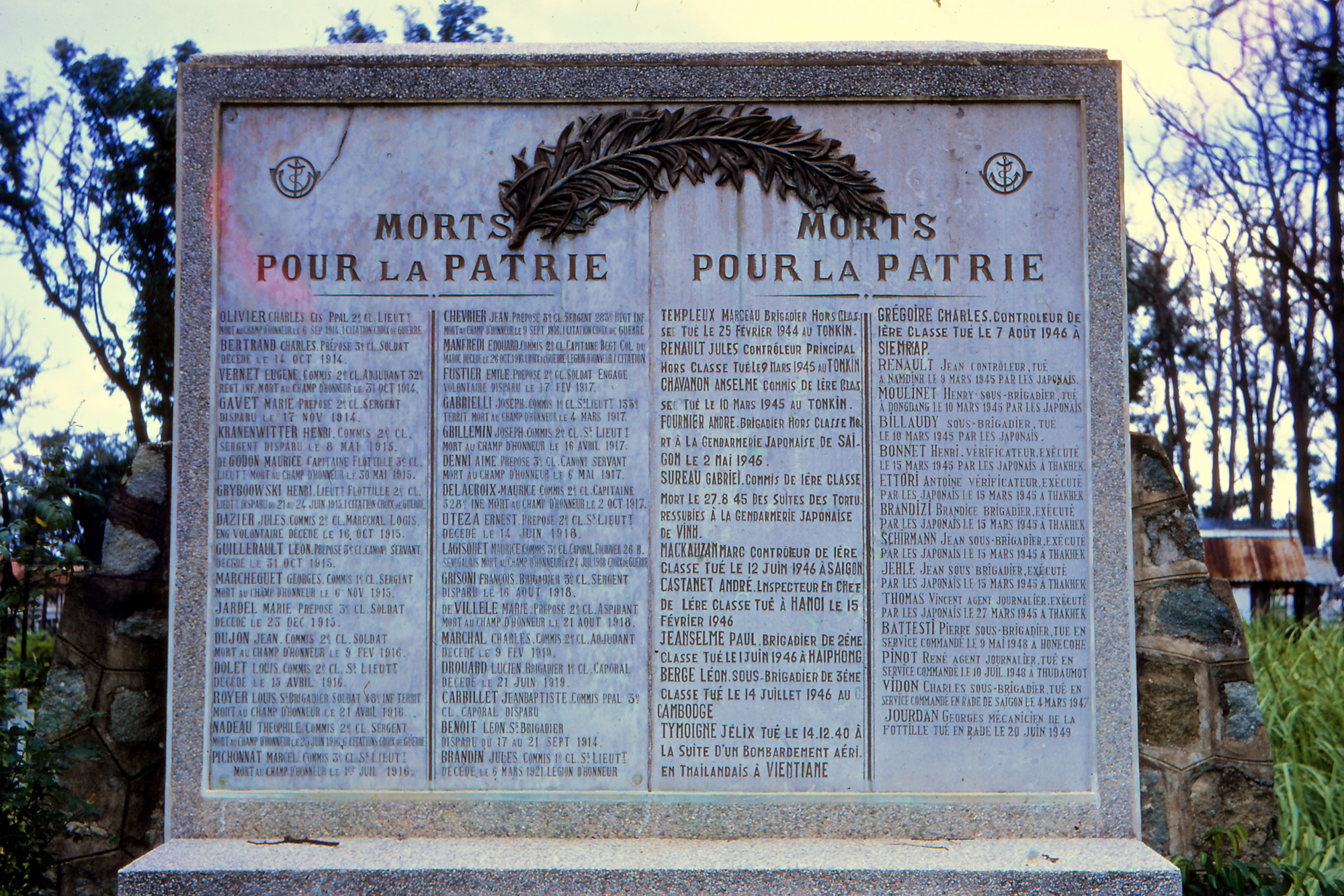

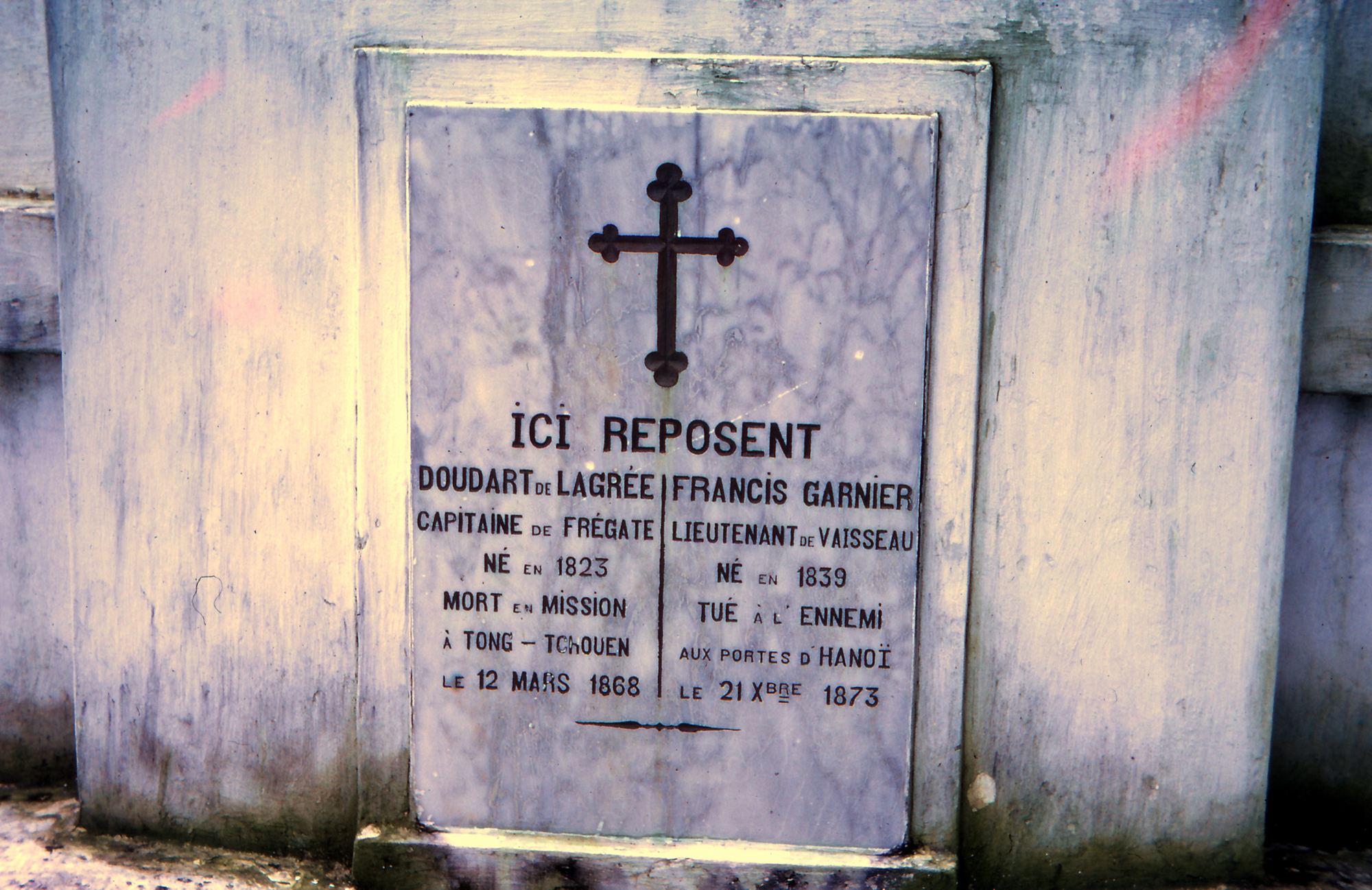

A 1970 photograph of a French military memorial in the Mạc Đĩnh Chi Cemetery, now Lê Văn Tám Park, by Frederick P Fellers (Indianapolis, USA)

This article was published previously in Saigoneer http://saigoneer.com

Cleared in 1983 to create the Lê Văn Tám Park, the former Massiges or European Cemetery (Cimetière Européen) was the most famous French cemetery in Saigon. To coincide with the release of hitherto unseen pictures of the cemetery taken in 1970 by Frederick P Fellers (Indianapolis, USA), we take a look at the history of this old Saigon institution.

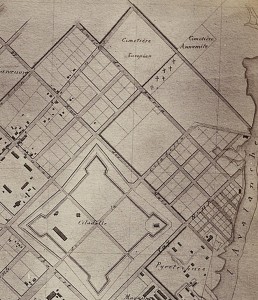

The European Cemetery (1859) and its later neighbour the Annamite [Vietnamese] Cemetery (c 1870) are both visible at the top of this 1871 map of Saigon

At the outset, it was administered by the French Navy as a military cemetery. Some of its earliest occupants included French marine infantry soldiers Captain Nicolas Barbé (beheaded at the Khải Tường Temple on 7 December 1860), Lieutenant-Colonel Jean-Ernest Marchaisse (killed at Tay-Ninh on 14 June 1866) and Captain Savin de Larclauze (also killed at Tây Ninh on 7 June 1868); and Mekong River explorers Captain L Doudart de Lagree (died 12 March 1868 while leading a geographic survey and exploration of the Mekong River into Laos and China) and Lieutenant Francis Garnier (killed 21 December 1873 in Hà Nội). By 1895, the cemetery contained 239 military graves.

During the 1870s, the European Cemetery acquired the popular name “jardin du père d’Ormoy” (Father d’Ormoy’s Garden), apparently because of the practice of the Navy’s Chief Medical Officer Dr Lachuzeaux d’Ormoy (1863-1874) of sending his most unruly patients to tend its lawns and flowerbeds.

A view of rue Legrand de la Liraye (now Điện Biên Phủ street) with the main gate of the European Cemetery on the right

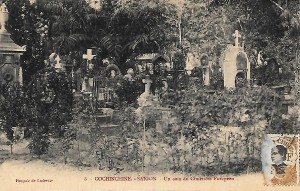

However, by the late 1860s, civilians were also being buried in the European Cemetery, a trend undoubtedly reinforced during the early years of the colony by the high mortality rate from serious endemic diseases such as cholera, malaria, intestinal parasites and dysentery. A report of 1889 noted that “although there exist in our colony none of the terrible epidemics that all too often afflict our possessions across the seas, a visit to the European Cemetery in Saigon may painfully reveal the truth about the victims of the climate.”

Intriguingly, the European Cemetery contained a relatively large number of tombstones with Germanic names, reflecting the preponderance of German merchant trading houses in Saigon, particularly before 1870. In one corner of the compound there was also a group of tombs belonging to a band of injured Russian seamen who had fled to Cam Ranh Bay in 1894 following their defeat at the Battle of Tsushima and later died in the military hospital in Saigon.

The main entrance to the European Cemetery

In around 1870, a smaller Vietnamese Cemetery (Cimetière Annamite or Cimetière Indigène) was opened immediately north of the European Cemetery. The street dividing the two compounds – modern Võ Thị Sáu street – was briefly named rue des Deux cimetières (Two cemeteries street) before it became rue Mayer in the late 1880s.

From the end of the 19th century, as standards of hygiene improved and the colony prospered, the European Cemetery became the last resting place of choice for Saigon’s colonial politicians and administrators, among whose number were architect Marie-Alfred Foulhoux (1840-1892) and city mayor Paul Blanchy (1837-1901).

On 14 December 1912, this transformation of the European Cemetery into a burial place for the colonial elite prompted a critical report by the Courrier Saigonnais newspaper.

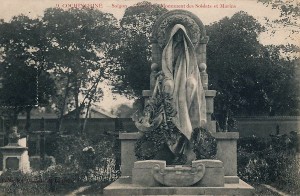

A military memorial in the European Cemetery

It pointed out that while the cemetery contained an ever-increasing number of grandiose and well-maintained tombs belonging to high functionaries, many of the original soldiers’ and sailors’ tombs had been left abandoned and overgrown with vegetation. It also singled out for criticism the “sacrilegious” practice of exhuming poor people’s graves within seven or eight years and relocating them elsewhere, presumably to make way for those of the rich and famous.

By the early 20th century, the interior of the cemetery was criss-crossed by pathways and planted with trees and shrubs by the staff of the Saigon Botanical and Zoological Gardens. It was surrounded by 2.5m high whitewashed walls, with its main gate in the southern wall of the compound on rue Legrand de la Liraye. This main gate was located directly opposite the northern end of rue de Bangkok, and after 1920, when rue de Bangkok was renamed rue de Massiges, the cemetery became known by the new name of Cimetière de la rue de Massiges.

A corner of the European Cemetery

Transferred by the French Navy to the care of the municipal authorities in the 1880s, the cemetery was administered thereafter by the Bureau du Conservateur des Cimetière, part of the Bureau du Service Régional d’Hygiène de Saigon, which had an office at 67 rue de Massiges (modern Mạc Đĩnh Chi street).

Many well-known figures of the later colonial era were buried here, including French naval officer Alain Penfentenyo de Kervéréguin (died 12 February 1946), missionary Grace Cadman (died 24 April 1946) and journalist and politician Henri Chavigny de Lachevrotière (died 12 January 1951). By all accounts, however, the most impressive tomb of that period was the grand mausoleum of Nguyễn Văn Thinh (died 10 November 1946), first President of the short-lived Autonomous Republic of Cochinchina (République Autonome de Cochinchine, 1 June 1946- 8 October 1947).

A 1928 photograph of the combined tomb of Mekong River explorers Doudart de Lagree and Francis Garnier

In March 1955, rue de Massiges was renamed Mạc Đĩnh Chi street, after the renowned Vietnamese scholar and diplomat Mạc Đĩnh Chi (1280-1350), and henceforward the cemetery also became known as the Mạc Đĩnh Chi Cemetery.

Over the subsequent two decades, a further generation of high-ranking politicians, military leaders and other prominent members of South Vietnamese society were buried within its walls, along with a small number of foreigners such as Time and Newsweek correspondent François Sully (died in February 1971).

However, perhaps its most famous occupants of this period were South Vietnamese President Ngô Đình Diệm and his brother and chief political adviser Ngô Đình Nhu, who were assassinated on 2 November 1963.

A Life magazine photograph taken in Mạc Đĩnh Chi Cemetery in 1961

In 1971, according to Arthur J Dommen (The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans: Nationalism and Communism in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, 2001), President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu had a section of the cemetery’s west wall demolished, apparently because a Cao Đài clairvoyant had relayed to him a message from Diệm’s ghost that since Thiệu was responsible for his death, the least he could do was to release his spirit from the cemetery!

However, ghost stories about the cemetery only really began to circulate widely after 1983, when the Vietnamese government decommissioned the Mạc Đĩnh Chi cemetery and transformed it into the Lê Văn Tám Park.

The destruction of the old Mạc Đĩnh Chi Cemetery was part of a wider project which also included the clearance of the French military cemetery at Bẩy Hiền intersection and the Pigneau de Béhaine Mausoleum near Tân Sơn Nhất Airport, as well as the old French cemetery in Vũng Tàu. Those with family members buried in these cemeteries were instructed to make arrangements for their reburial within two months. Unclaimed remains were cremated and relocated elsewhere. French military remains were repatriated to France for final burial in Fréjus, where a memorial was raised in their honour.

A 1967 photograph of a Vietnamese tomb in the cemetery

While the Lê Văn Tám Park which replaced the Mạc Đĩnh Chi Cemetery has since become a popular place for recreational activities, there are still many superstitious locals who prefer not to go there because of its previous history.

Today, the park is dominated by a Socialist Realist sculpture of the eponymous Lê Văn Tám, a young Vietnamese revolutionary martyr of the First Indochina War who is said to have destroyed a French fuel store at Thị Nghè in January 1946 by deliberately soaking himself with petrol and then turning himself into a “human torch” before jumping into the nearest petrol storage container. After 1975, many schools, parks, cinemas and streets were named after Lê Văn Tám, but in 2005, leading historian Professor Phan Huy Lê of the Hà Nội National University showed that while revolutionary forces did destroy the Thị Nghè fuel store in January 1946, the story about Lê Văn Tám was a fictional one, written by then Propaganda Minister Trần Huy Liệu.

An artist’s impression of Lê Văn Tám Park after completion of the planned underground car par project

In August 2010, ground was broken on a new project to build an underground car park beneath Lê Văn Tám Park, with space for 2,000 motorbikes, 1,250 cars and 28 buses and trucks. However, it was recently reported (http://vnre.blogspot.com/2011/04/le-van-tam-underground-car-park-project.html#sthash.bh6KCg3O.dpuf) that due to formalities relating to the issuance of a land-use certificate and exemption of land use fee as well as a change to the project’s technical planning, no progress on this project has yet been made.

The following images of the Massiges Cemetery, taken in 1970, were kindly provided by Frederick P Fellers (Indianapolis, USA):

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.

Where did the remains of Diem and Nhu eventually go? Very curious…

I was told they were reburied in a cemetery in Lai Thieu, must go out there and have a look sometime