Chợ Lớn – barges in front of a rice factory

George Dürrwell spent nearly three decades working for the Cochinchina legal service. His 1911 memoirs, Ma chère Cochinchine, trente années d’impressions et de souvenirs, février 1881-1910 (My Dear Cochinchina, 30 years of impressions and memories, February 1881-1910) afford us a fascinating picture of life in early 20th century Saigon and Chợ Lớn. This is part 3 of a three-part excerpt from the book.

To read part 1 of this serialisation, click here.

To read part 2 of this serialisation, click here.

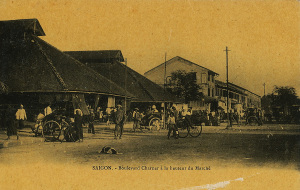

Let’s now complete our fantastic journey through the streets of Saigon, transporting ourselves along the boulevard Charner, that wide thoroughfare which runs parallel to the rue Catinat and which, in its animation, is somewhat reminiscent of one of the dreary main avenues in the dull city of Versailles. The boulevard runs from the central market as far as the new City Hall.

The old Saigon Central Market (1870-1914) on boulevard Charner

A market is always an interesting place to visit, and in every town and village here, it offers the astute observer an opportunity to observe an infinite variety of real-life scenes which reflect local customs. Each market is also a small agricultural show, where the region’s key products are all grouped together. In the Central Market of Saigon, where there is the most variety, Europeans and Asians – Annamites, Chinese and Indians – mingle and jostle, making such a visit even more captivating.

Yet how few of my fellow citizens have ever set foot in the Central Market? I don’t reproach them for this, having ignored it myself for many years, simply because of my lazy reluctance to get up at the early hour when it is at its busiest. However, I finally decided to visit, and if you make the effort to do the same, I can assure you that you will not regret it.

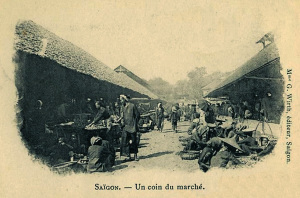

A corner of the old Saigon Central Market on boulevard Charner

Moreover, the time left to see this market is now short [at the time of writing, the new Halles Centrales, new Bến Thành Market, was being planned]. It seems, in fact, that all the picturesque corners of our old Saigon, of which the dilapidated, rotten, yet so characterful old Central Market is the real centre of attraction, are now condemned to disappear. It’s not for me to discuss here the rights and wrongs of this measure, although I have every reason to believe that not everyone will lose out as a result of the change. But let’s not dwell on this subject.

So, here we are in the old Central Market: it is 7am, and around us is an intense and noisy scene with traders and customers swarming incessantly back and forward.

Another market scene

Here, in long rows at the edge of the sidewalk, one can see big baskets covered with large woven mesh, which serve as temporary cages for the various types of poultry brought every day by the little tram from Go-Vap. Nearby are piles of indigenous vegetables from the same source, including sweet potatoes and those long white turnips which grow in abundance on the sandy plains of Hoc-Mon.

Next to them, under the watchful eyes of merchants from the countryside, are spread out the seemingly infinite varieties of fruit which are produced throughout the year in this fertile land of Cochinchina. According to the season, these include: juicy yellow mangoes; mangosteens with their tasty white pulp; large oranges from Cai-Be, whose rough green skin contrasts starkly with the gleaming brilliance of small golden tangerines; bulging watermelons with rose coloured flesh; fragrant guavas; bunches of fresh indigenous lychees covered in spines which make them look like tiny curled hedgehogs; and more, many more. Not to mention the mountains of green and yellow bananas, that veritable national fruit of the earth in the land of Nam-Ky.

The front of the old Saigon Central Market on boulevard Charner

Further on, market gardeners from the suburbs obligingly spread out their green wares, pale reproductions of our vegetables from Europe, in the middle of which, marking a cheerful note, sit piles of scarlet peppers.

There, in a dark corner of the market, are the Chinese butchers, their appearance and that of their wares leaving much to be desired. They do business side by side with collectors of old scrap, rags and other rubbish. Frankly, that area is not the most attractive place to shop.

And here is the fish market, the best-stocked part of the market, but also the smelliest, due to the acrid and sickening stench of the muddy water.

Tough Indian collectors working for the market administration circulate, demanding sapeks from the traders. Their demands are often resisted loudly by the Annamite merchants, especially the women, and the police are frequently obliged to intervene.

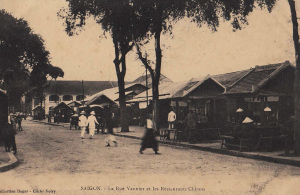

Chinese restaurants on rue Vannier

Along the rue d’Adran [Hồ Tùng Mậu street], right outside the market, small open-air Chinese restaurants are set up on rough benches. It’s here that our cooks and boys line up and gorge themselves at our expense on a variety of steaming concoctions, washed down with a fine drop of choum-choum.

The immediate vicinity of the market, especially the rue d’Adran, is as interesting to visit as the main market pavilions. Watching the crowds of people going back and forth busily in the narrow alleys, it feels like one has been transported into one of the most populated areas of the city of Cholon; indeed, apart from some merchants of Indian fabrics whose shops line the rue Vannier [Ngô Đức Kế street], Chinese commerce reigns supreme here.

On the occasion of the great religious and family celebration of Tết, the market lies idle for two days, and during this period it is impossible to find even a radish in exchange for its weight in gold.

The Hôtel de ville (Town Hall) soon after its inauguration in 1909

The new City Hall is another great attraction of the boulevard Charner, located at the top end of the street. Like the Swing Bridge across the arroyo Chinois, this building has attracted much attention from the press, most of it lukewarm.

It can’t be disputed that the City Hall presents, both as a whole and in its detail, big imperfections. The main entrance steps, which should rise high above the ground in order to comply with the most elementary rules of perspective, exist only in a rudimentary state; the central belfry, which claims to recall the elegant architecture of some city halls in Flanders and the north, is narrow and mean; and the main interior staircase is woefully lacking.

However, these gaps are largely redeemed by the admirable salle des fêtes, that most essential part of the building, even devoid of the lavish artistic decoration that has been bestowed on it, which is really worthy of our beautiful Saigon.

The salle de spectacles of the Hôtel de ville (Town Hall)

It is supplemented by other rooms especially assigned to the municipal council or reserved for weddings, including a charming reception room.

The solemn inauguration of the Town Hall took place just a few months ago, in February 1909, in the presence of the Governor General of Indochina, and it had the happy inspiration to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the French occupation of Saigon. The loyalty of the Annamites of Cochinchina was affirmed, on this occasion, by the willingness of all to respond to the invitation of the Mayor.

To follow the example of our cities in France, and especially the cities of the southwest, which, without exception, have spawned at least one great man, Saigon has decorated some of its squares with statues. However, these monuments have the merit of reviving genuine national or colonial glories. As for local celebrities, it has wisely been decided that for now their names should simply be given to streets in the city. Sic itur ad astra [“Thus you shall go to the stars,” from Virgil’s Aeneid book IX]

The statue of Admiral Rigault de Genouilly

Next to the Saigon River, facing the naval port, stands the figure of Admiral Rigault de Genouilly, that glorious sailor to whom France owes the conquest of the old capital of Nam-Ky, and who now seems to contemplate the scene of his former exploits from the top of his pedestal. Some 30 years ago, the inauguration of his statue was the object of a great patriotic gathering to which the entire population Saigon was invited.

The inauguration of the Rigault de Genouilly statue was an occasion which lacked nothing in solemnity: the highest authorities of the colony praised the hero of the day in the most generous terms; land and sea troops marched in parade in front of him; a poet celebrated the Admiral in pompous Alexandrine verse; and the youth of local schools performed a cantata featuring the chorus: Come, children of Annamite France, To the land of steam and electricity!

And in those few happy words was summarised the whole of our future programme.

The monument to Ernest Doudart de la Grée

Nearby, a modest pyramid was erected in memory of the famous explorer Ernest Doudart de la Grée. The description of this monument can be found in a technical report to the municipality by one of our former councillors: “It is,” says the report, “a monolith composed of three cemented blocks of granite.” So now you know.

Nor have we forgotten Commandant de la Grée’s faithful companion, the valiant Mekong River explorer Francis Garnier, who remains one of the purest and most sympathetic figures among our early Indochinese pioneers.

The statue of Francis Garnier

We gave his name to the small square in front of the place du Théâtre and erected a statue there to his memory. Dressed in his naval officer’s uniform, he seems ready to draw his sword in the service of colonial France, to the greatness of which he devoted his entire life. I must admit, however, that the attitude of the statue reminds one greatly of the Jean Rapp monument in one of the squares of the old Alsatian city of Colmar, and it is not the most attractive to look at.

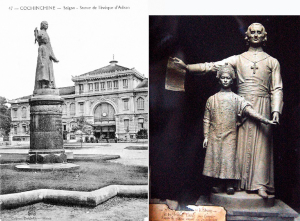

Occupying pride of place in the place de la Cathédrale is a statue of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran. In the last years of the 18th century, he was a wise counsellor to the great Emperor Gia Long, and the true inspirer of the Versailles Treaty which opened up Annam to French influence.

The Pigneau de Béhaine statue which once stood in front of the Cathedral

The statue, inaugurated in 1902, is the work of our friend Édouard Lormier, the author of the Monument aux sauveteurs (Lifeguard Memorial) in Calais, who created a real tour de force by treating a rather awkward subject with great artistic originality.

The statue depicts the venerable prelate in a standing pose, presenting him as a tall and commanding figure, thanks to his long, tightly buttoned cassock and the narrow plinth on which he stands. At his feet, in ceremonial costume, is his beloved pupil, the little prince Canh, eldest son of Gia Long, to whom he is seen presenting a copy of the alliance and pact of friendship signed between the two kingdoms. The physiognomy and attitude of the child is also charming, and the group, though somewhat mannered, creates, in short, a beautiful overall effect.

The Gambetta monument

Nearby, in the midst of the shaded lawns of boulevard Norodom, is Léon Gambetta himself. Wrapped in a large fur coat which seems somewhat inappropriate in our sunny Cochinchina, the great orator stands, head slightly thrown back, apparently addressing the crowds. His extended right arm seems to envelop the whole city with a sweeping and protective gesture. The two subjects flanking the monumental pedestal – a sailor and a mortally wounded naval infantryman – cut a fine figure, recalling the glorious role played Gambetta in the epic of the Défense nationale. The statue inspires the relentless admiration of all the good Nha-que who visit the capital.

French statesman Léon Gambetta (1838-1882)

In fact, the Gambetta monument on boulevard Norodom has a history that could serve as a theme for some amusing production in the Théâtre du Palais-Royal. Here it is in a nutshell.

The premature death of Gambetta, which inspired genuine public mourning in France, also caused deep emotion here in Cochinchina. In response, seeking to interpret faithfully the common sentiment, our local assembly decided to perpetuate his memory by raising a dignified statue to him in one of our Saigon squares. The funds were voted by acclamation, and one of our honourables, then on leave in Paris, was charged with commissioning the work.

Our man, thus given a mandate, made his choice among the great artists of the capital, and that choice was good; a few months later, the desired monument arrived safely. Everything was going well.

Another view of the Gambetta monument

But we had reckoned without the patriotic zeal of our deputy. The confusion resulting from his informal intervention was not long in coming. One morning, the mayor was informed that another large box labelled “statue – fragile” had just arrived at his address. A duplicate statue had been mistakenly produced and delivered to Saigon. The excitement was great, but so was the embarrassment, because a large monumental statue is rather more difficult to refuse than a simple parcel sent cash on delivery. The Mayor had a good practical solution: the duplicate was given to the deputy who had rashly ordered it, and he was obliged to pay for it. It was cruel but logical, and in our good Cochinchina, where money comes easy, a compromise solution was not even offered. In this way, Saigon is even now in possession of two Gambetta statues. The one we all know is proudly located in the sunlight of boulevard Norodom, while the other is stored and long forgotten, buried for years in the white wooden coffin in which it once made its long and unnecessary trip to our overseas territories.

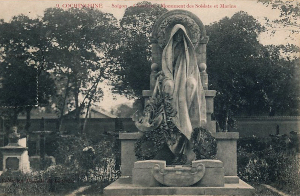

The main gate of the European cemetery

Arriving at the end of the long avenue lined with sao trees named rue de Bangkok, one reaches the entrance to the great Saigon necropolis, which is open to all.

It is here that Cochinchina keeps the remains of officials who have fallen foul of the deadly climate, old disillusioned settlers who have succumbed to hard work, bright future officers struck down far too early and poor young soldiers whose weeping mothers wait in vain for their return. Here they all sleep side by side, and alas, there are far too many of them!

The Saigonnais, who are always rather careless about tomorrow and even cheeky in the face of the death that awaits them, refer to this large cemetery by the graceful name of the “Jardin du père d’Ormay” (Father d’Ormay’s Garden).

A military monument in the European cemetery

In order to explain this etymology, I must tell you that the said Father d’Ormay whose sympathetic memory has indeed remained very much alive in Saigon, once occupied the high functions of Director of the Public Health Service and of the Military Hospital.

Pierre Loti dedicated some beautiful pages of his work L’Indochine Coloniale – Un Pélerin d’Angkor to a description of this special garden. In heartfelt lines of poignant melancholy, he spoke of these French graves, dug so far from the land of France. However, none of them has been completely abandoned, and in default of family, all of the deceased may still count on a friendly hand to care for their graves and make floral tributes.

Saigon also has two other public parks, large exotic gardens with shady paths and flowerbeds. However, with the exception of the days of “La Musique,” they attract fewer visitors than the gloomy park we just left.

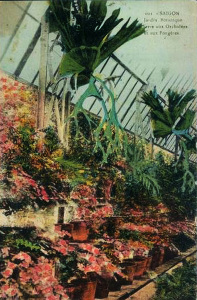

The orchid house at the Botanical Gardens

Only the Botanical Gardens sometimes offers asylum to amorous couples fleeing from prying eyes; indeed, if the plants in some mysterious corners of the orchid house could talk, they would undoubtedly disclose some curious revelations about the romantic intrigues which take place there. But hush! Let’s remain discreet and not interfere in matters that do not concern us.

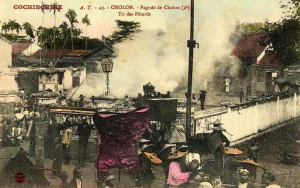

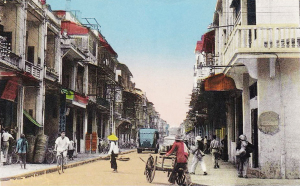

Located at a distance of about four kilometres from Saigon, at the other end of the dreary Plain of Tombs, stands the Chinese city of Cholon. This is the “big market” of the colony, the rich industrial and commercial warehouse of our Cochinchina.

Two tramway lines and several roads connect the two cities with each other; and in the future, a wide boulevard will link them even more closely: however, a great many interests of all types, both public and private, are engaged in this enterprise, so we may have to wait a long time for its completion.

Junks being loaded in Chợ Lớn

Of all the channels of communication between Saigon and Cholon, the busiest and most active is unquestionably the arroyo Chinois [Bến Nghé Creek], the waterway along which the rice of fertile Cochinchina flows incessantly, from Cholon with its large factories to the port of Saigon where the international cargo ships are moored.

In order to account properly for the inexhaustible richness of this wonderful land of promise, it is necessary to travel, during the working hours of the day, along the Binh-Dong and Binh-Tay quays where rice paddy undergoes successive transformations in the large steam rice mills. It is here, from dawn to dusk, that we encounter at first hand the relentless hard work on which our economy is based.

Massive junks hasten, bow to stern, along the waterway, loading and unloading again and again.

Junks on the arroyo Chinois in Chợ Lớn

Half-naked Chinese workers walk back and forth between the junks and the vast stores, their spines bent under the weight of heavy gunny sacks packed with grains.

Nothing interrupts the work of these beasts of burden; and one can not help admiring their tireless stamina, a vaguely disturbing activity that a whole race knows so well as their daily business of life.

It is by design that I refer to a vague uneasiness and apprehension about the hard work of the Chinese, because the coin has two sides. We must remember that these great labourers work only for themselves and for their country; all the money they amass so patiently, sapek by sapek, invariably leaves the producer countries and makes its way back to China, and there can be no doubt that its owners would follow at the first opportunity.

The departure of a junk in Chợ Lớn

In fact, with just a few exceptions, the Chinese merchant who has settled in our country is not fixed here. His only desire, his only dream for the future, is to make a fortune and then to return to his homeland. Ideally he will achieve this while he is still alive, so that he can enjoy with his family the fruits of his labours acquired abroad. However, if he only manages to return after his death, he will at least sleep peacefully in the field alongside his ancestors, near the family altar on which incense sticks will be burned to honour his memory.

A street scene in Chợ Lớn

An article published in the journal Dépêche coloniale under the title “The True Yellow Peril” (1 October-November 1909) is a well-documented study of this financial exodus which we suffer without being able to stop it. All those who have concern for the future of our colony will read it with interest and meditate fruitfully on its wise conclusions.

In the evenings, Cholon turns into a real fairyland city. Everywhere in the crowded streets and squares, in the markets and even in the shops and open-air restaurants that line the roads, countless lights shine out into the night. Among them, forming the keynote of this illumination, are large lanterns of isinglass on which Chinese characters are painted in large brush strokes, indicating the names of the proprietors and their multiple professions – the thousand and one trades in which the good Chinese, without distinction, are masters.

Gradually, the clubs begin to light up in their turn; theatres open their doors; brohels, gambling and opium dens prepare quietly to receive their customers; and all Cholon, that which we know and that which remains for us mysterious and closed, begins its search for pleasures more varied than innocent, a relaxation to the labour of the day.

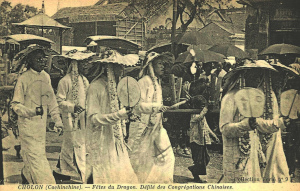

Representatives of the Chinese congregations taking part in the Procession of the Dragon in Chợ Lớn

Once a year, in early May, all Saigon travels to Cholon to attend the ritual “Procession of the Dragon,” which makes its way from pagoda to pagoda through the crowded streets of the city.

The Procession of the Dragon is a veritable feast of beautiful and colourful Chinese silk costumes and banners, which shimmer in the bright Nam-Ky sunlight. The banners seem to float in the wind, proudly displaying in broad embroidered characters the names and slogans of each Chinese congregation. Meanwhile, those taking part in the procession wear elegant silk festival costumes in soft shades of azure blue and mauve. Some carry subtlely decorated silk umbrellas.

But the undoubted highlight is the group of adorable Chinese children who play a major role in the procession. Their heavily made-up little faces and colourful silk costumes seem to transform them into cute, finely-modelled wax dolls.

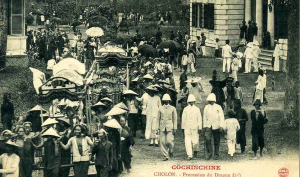

The Procession of the Dragon reaches the grounds of the Inspection de Cholon

Some ride on richly-decorated horses, while others are perched high on a float, where they emerge curiously from a gigantic blossoming pink or white lotus flower. Their hieratic appearance and apparent imperturbability complete the illusion; and we realise that all of the children are fully aware of the important role they play in the ceremony. Meanwhile, attentive and anxious fathers follow their brood step by step, ready to jump in and save them at the first sign of a fall or an accident.

Finally, at the very end of the procession, marches the hero of this great celebration, the fantasy dragon of Chinese legends. Its body, which exceeds 30 metres in length, is made from a rattan frame concealed by wide bands of scarlet silk, decorated with sparkling sequins. It is carried by a troupe of around 20 young men. The mission of those half-hidden under its body is to give the monster the appearance of life by recreating the soft undulations of a creeping beast. However, the real virtuoso of the troupe is concealed beneath the grotesque head, which moves up and down relentlessly until the final great ritual, in which the dragon bows down before the Mayor of Cholon as the crowd of onlookers presses around him.

Firecrackers explode in the grounds of a Chinese Assembly Hall

The festival ends with the crowd storming a mountain of Chinese food, meats, cakes and sweets which has been set out in front of the Pagode des Sept-Congrégations. Needless to say, the assailants don’t take very long to devour everything.

Then, in the evening, the pagodas light up; noisy firecrackers explode everywhere and the feast continues more intimately in restaurants and private houses, not stopping until long into the night.

Close to Cholon’s busy industrial and commercial centre, one may find a quiet city of charity where all who are suffering may find succour and assistance, regardless of the nature of their infirmity. Thanks to this admirable initiative, the area contains a range of support establishments which can meet every need.

The Drouhet Hospital in Chợ Lớn

There is the Hospital Drouhet, a model hospital with wards and operating rooms equipped in accordance with the most modern rules of hygiene and comfort, and where the Europeans of the colony, officials and settlers, may find the illusion of home and all the amenities they can reasonably desire.

The natives have, moreover, not been forgotten and a beautifully landscaped hospice has made available to them.

Next to the Hospital Drouhet rise the elegant buildings of the Maternité, where all young expectant mothers, are welcomed and treated without distinction. A school for native midwives has been annexed to this building, which has become very popular with the local people, rendering invaluable service to the business of Annamite birth, once so neglected and so culpably compromised.

The Maternity Hospital in Chợ Lớn

Nearby is an asylum for blind children, where around 40 youngsters learn, alongside the first elements of primary education, the manual trade that will keep them later from want and ensure that their daily rice bowl remains full. This asylum is maintained under the intelligent direction of a French teacher who is also blind. Among all the infirmities that afflict our poor and unbalanced humanity, deprivation of sight has always seemed to me the most unjust and the most cruel. Thus, my concern has always been carried by preference towards those who are afflicted by it. If you agree with me, go and visit the blind children of Cholon: by the time you leave, your heart will be overflowing with charity.

Unfortunately, a nearby project devoted to the education of deaf children did not give as good practical results, for competitive reasons that it is better not to mention.

Rue de Canton in Chợ Lớn

Finally, to end our pilgrimage, there is an old people’s asylum, created with the ingenious idea of providing facilities for elderly men and women without families who previously displayed their decay and misery on the streets of the city. I once made an official visit to this place and was saddened to find that one of its residents was the nephew of the great patriot Phan-Tan-Giang.

It was in the midst of this group of model institutions that the Société de Protection de l’Enfance (Child Protection Society), with the generosity of the Chinese city, built its orphanage on a gracefully conceded plot of land. More than 60 children, mostly those of mixed race who had ruthlessly been abandoned by their fathers, are currently sheltered and raised here. This work fills an important gap in social provision, and thus happily completes the works of the charities to which the administration of the city of Cholon is honoured to attach its name.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.