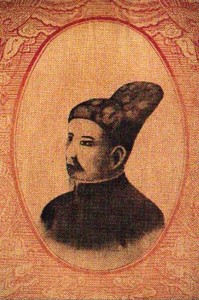

Pétrus Ký (1837-1898) in 1883, aged 46

In 1885, scholar Petrus Trương Vĩnh Ký delivered a lecture at the Collège des Interprètes entitled Souvenirs historiques sur Saïgon et ses environs (Historical Memories of Saigon and its Environs). Published as a booklet later that same year, it provides us with one of the most important historical accounts of Saigon-Chợ Lớn in the pre-colonial period. The text has been translated into English and this is part one – the rest will be serialised here over the next few weeks.

Gentlemen,

The city of Saigon has undergone a complete transformation since the day when the French flag replaced the yellow Annamite [Vietnamese] flag in this country. This change began in 1859, taking place gradually but unceasingly, and it is to this that we owe the pleasant appearance with which the capital of Lower Cochinchina now presents itself.

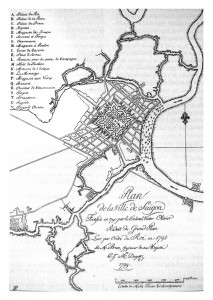

Saigon in 1795

Today I want to trace a tableau of both old and modern Saigon, bringing the two descriptions together in such a manner as to compare and contrast the differences between the states of civilisation in two epoques separated by just a quarter of a century.

One hopes to preserve the memory of a place, especially when it was the scene of so many events that have occurred in such a short space of time, each obliterating traces of the other.

Historical traces are the links that tie together the epoques of nations, and often of states which have disappeared into oblivion. Factual memory weakens in proportion to the number of successive generations. These continuous changes are a necessary condition of the life of things and of peoples, but the memory of them would be altered if history did not set them down in writing at times, in order to preserve their character.

This Saigon which we regard with indifference today has witnessed events that excite our curiosity, because they have not yet entered the domain of history, but in future they will arouse passionate interest from our successors. Therefore, let us take a walk through old Saigon, let’s visit all of its parts and make an account of our observations, both geographical and historical.

So what was Saigon like in times gone by? Before and during the reign of Gia Long? During the reigns of Minh Mạng, Thiệu Trị and Tự Đức? And what was its appearance at the time of the arrival of the French?

The name “Saigon”

This 1815 map shows the “Saigon Market” in what is now Chô Lớn

Before describing the ancient citadel, it’s first necessary to find out where the name we give our city originated.

Saigon was originally the name given to the current Chinese city. According to the author of the Gia Định thông chí (Description of Lower Cochinchina), Sài was a borrowed word in Chinese characters meaning “wood,” while Gòn was the Annamite name for cotton and the cotton plant. The name comes, it is said, from the amount of the cotton that Cambodians planted around their ancient earthworks, whose traces still remain at the Cây May Pagoda and surrounding areas.

To us, it seems that the name can only be that which the Cambodians gave to this country and which was later applied to the city. However, I have still not yet been able to ascertain its true origin.

The city of Saigon was so called by the French, who found the name on European maps of bygone days, which designated the city under this general but vulgar denomination, sometimes used to describe to the entire province of Gia Định.

Saigon before Gia Long

Saigon before Gia Long was, it seems, little more than a simple Cambodian village. However, in 1680 it was, for a certain time, the residence of the second king of Cambodia.

According to history, the country was invaded peacefully by Annamites under the leadership of the government of Huế in 1658, during the reign of Nguyễn Phúc Tần, lord of the south.

The countryside around Saigon

After having conquered the territory of Champa (Chiêm Thành) by driving back its former inhabitants, the Annamites found themselves neighbours of the Cambodians (Khmer people), whose mind had been influenced by the success of the Annamites (“children of the celestial king”). The settlement soon became much larger following settlement by Chinese supporters of the Ming dynasty, which was permitted and encouraged by the court of Huế.

In 1680, two senior commanders of the Ming troops, preferring to serve the Annamites than to submit to the Qing, the Manchu Tartars who were the new conquerors of China, came in 60 junks to Tourane, followed by 3,000 soldiers, with the aim of establishing themselves there. They sent a request to this end to the lord of Huế. The King of Annam, after treating them to a banquet, gave them a letter to show to the King of Cambodia, asking permission for them to settle in Cochinchina and exploit its vast wastelands. Arriving at Đồng Nai, they divided into two groups; one settled in Biên Hòa, while the other headed for Mỹ Tho.

One of the two kings of Cambodia lived at Gô-bich, while the second king lived in Saigon. The latter, finding himself threatened on one side by the Chinese of Mỹ Tho and on the other by those of Biên Hòa, wrote to the king of Huế asking him to intervene to prevent the intrigues of his protégés.

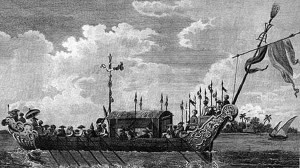

Boats on the Saigon River

The king of Huế set himself up as the arbiter of this dispute and undertook to resolve it. For this purpose, he sent General Văn in an expedition against the Chinese and against the king of Gô-bich, who took refuge in strong fortresses, barricaded the Mekong River with iron chains, and thus impeded trade with the Annamites.

After having defeated the Chinese at Mỹ Tho, this general moved forward to Gô-bich. The first king, Néâch-ông-thu, then retired to Oudong and finally concluded a treaty with the Annamite general, who left Cambodia and returned to Bến Nghé (Saigon)

One year later (1684), Néâch-ông-thu was unfaithful to the execution of the treaty. Nguyễn Phúc Tần (King of Huế) sent Nguyễn Hữu Hào to declare war on him. The king of Cambodia was taken prisoner, and soon after arriving in Saigon he was taken ill. The second king, then resident in Saigon, killed himself.

His son, Néâch-ông-yêm, was placed on the throne and installed at Gô-bich by the Annamites.

The intervention of the court of Huế led to immigration by Annamite settlers, who, encouraged by the government, gradually occupied the country. This permitted Lord Nguyễn Phúc Chu in 1698 to establish prefectures, sub-prefectures, townships and villages and to create, for this country, an administration similar to that of the rest of the kingdom of Annam. First Biên Hòa and Gia Định formed themselves into a phủ [prefecture], subdivided into two huyện [districts]. From this came the name người hai huyện (people of the two districts), to describe the residents of Biên Hòa and Gia Định.

A late 18th-century Nguyễn dynasty warship

In 1772, the Tây Sơn (montagnards of the west), Nguyễn Nhạc, Nguyễn Lữ and Nguyễn Huệ, revolted against Huế; and at the same time, the Trịnh (Trịnh Sâm) came to attack the city of Huế. Lord Nguyễn Phúc Thuần and his nephews Nguyễn Phúc Đồng and Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (later King Gia Long) took refuge in 1774 in Gia Định (Đồng Nai), Saigon.

For 15 years, Gia Long was chased and hunted by the Tây Sơn. He returned from time to time to Saigon, but stayed there very little and was driven out by his enemies who, from Qui Nhơn, constantly returned to the offensive.

Saigon under Gia Long

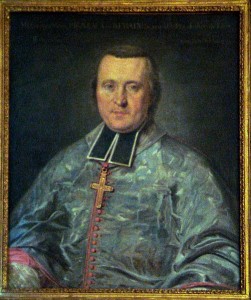

It was in 1789 that Gia Long, after taking over the city of Saigon which had previously been occupied by the Tây Sơn, built the first citadel, and I will indicate the former location and traces of this in relation to the territory of modern Saigon. In 1788, Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran, apostolic vicar in Cochinchina, who took Gia Long’s son Prince Cảnh with him to France to ask for help, returned to Saigon with French officers. By this time, Gia Long had already retaken Saigon and established himself there.

The following year, Gia Long built the ancient citadel of Saigon, under the direction of Monsieur Ollivier, engineering officer.

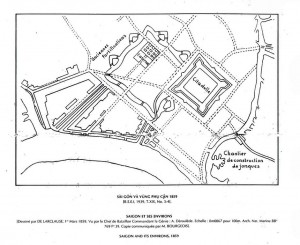

A 1795 map showing the location of the 1790 Gia Định Citadel

It took the approximate form of an octagon (a shape insisted upon by Gia Long himself) with eight gates, following the shape of the Bát quái [bāguà 八卦, the eight trigrams used in Taoist cosmology] and representing the four cardinal points with their subdivisions.

The citadel, including its moats and bridges, was built of large Biên Hòa stones. The height of the wall was 15 Annamite cubits (5.20m).

The centre, where the flag tower stood, was located approximately in the vicinity of the present cathedral. From its summit, one could see very far into the distance. It extended: from south to north along modern rue Mac-Mahon [Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa] up to the wall of the later [1837] citadel, which was destroyed by the French, and from east to west from rue d’Espagne [Lê Thánh Tôn] to the rue des Moïs [Nguyễn Đình Chiểu].

To the east were the two front gates (cửa tiền). The one called the Gia Định Môn overlooked the square and the Canal du marché de Saigon [Nguyễn Huệ boulevard]; the other, Phiên An Môn, was in the vicinity of the Naval Artillery, on a street which ran along the canal de Kinh Cây Cám.

The rear wall to the west also had two gates: the Vọng Thuyết Môn and the Củng Thần Môn, facing in the direction of the second and third arroyo de l’Avalanche bridges [Bông and Kiệu bridges over the Thị Nghè creek].

The left side of the citadel looked north, with two gates: the Hoài Lai Môn and the Phục Viễn Môn, overlooking the first arroyo de l’Avalanche bridge [Thị Nghè bridge].

An 1859 map of Saigon showing the locations of both the 1790 and 1837 citadels

The right side of the citadel had the Tĩnh Biên Môn and the Tuyên Hóa Môn gates, located on rue Mac-Mahon [Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa]; one opened onto the route Stratégique [Điện Biên Phủ], and the other onto the route Haute de Chợ Lớn [Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai, Trần Phú].

The Gia Định Citadel was occupied by Gia Long for 22 years, during which time he went every year in expedition against the Tây Sơn, in seasons when the monsoon was favourable.

The funeral of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine

As the funeral of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine took place in Saigon at this time, we will digress for a moment to attend the ceremony in which both religion and royalty were impressively represented.

After his return from France, the Bishop of Adran lived in Saigon, in a house that Gia Long had built for him on the outer corner of the Citadel, at the location where the gunpowder magazine is located, called the Dinh Tân Xá [Tân Xá Palace]. The Christians of Thị Nghè had their church close by, on the edge of the creek, and this formed part of the parish of Tân Sơn where the tomb of the bishop is located now.

The Monsignor had built a country house there, where he would occasionally relax with his pupil, Crown Prince Cảnh.

Pierre Joseph Georges Pigneau, Bishop of Adran (1741-1799)

Prince Cảnh was sent to the siege of Qui Nhơn. At the urging of Gia Long, the Bishop accompanied him to serve as his mentor. But after 33 years of a very rough and laborious life, Pigneau was attacked by acute dysentery.

Gia Long, driven by a genuine affection for the prelate who had rendered him the most eminent services, sent his best doctors and used every possible means to preserve his life. Prince Cảnh came every day to visit his tutor, and Gia Long himself came several times to see his benefactor, despite his preoccupation with the siege of Qui Nhơn, from which he tore himself away out of a sense of gratitude.

On 9 October 1799, the bishop died in the arms of Monsieur Lelabousse, the missionary who had accompanied him; he was 58 years old. Gia Long, having received the sad news of the death of his illustrious guest, sent a beautiful coffin along with silk to wrap the body. On 10 September, his body was placed on one of the king’s ships for the return to Saigon, where he was to be buried.

Arriving in Saigon on 16 October, his body was placed in the episcopal palace, where it remained on view for two months.

Prince Cảnh, who had accompanied the body of his tutor, considered himself a disciple and eldest son of his master the prelate, for whom he was in deep mourning. He had a special temporary palace built opposite the bishop’s house, and stayed there day and night, receiving many mandarins who came from all parts of the kingdom to render illustrious funeral honours to the deceased.

Gia Long finally returned from Qui Nhơn. To show his gratitude to the prelate, he presided in person at the funeral ceremony. The funeral took place on 16 December 1799 at Tân Sơn, about 5km from Saigon.

King Gia Long (1762-1820), born Nguyễn Phúc Ánh

Prince Cảnh was responsible for leading the procession, which set off at around 2am.

A large cross, formed from artfully-arranged lanterns, was carried at the head of the procession, followed by a series of elaborately carved red and gold portable shrines, each held aloft on an ornate dais and carried by four men.

In the first were four characters of gold, 皇天主宰, Huáng tiān zhǔ zǎi or Hoàng thiên chúa tể, meaning “Sovereign Lord of Heaven;” in the second was an image of St Paul; and in the third an image of St Peter, patron of the Bishop of Adran. The fourth contained an image of the guardian angel and the fifth an image of the Blessed Virgin.

Then came a great standard measuring some 15 feet in length and made from damask, on which were embroidered in gold letters the titles conferred on the Bishop of Adran by the Kings of France and of Cochinchina, as well as those of his episcopal office. After this came a litter housing the insignia of the prelate, his cross and his mitre, which was carried directly in front of the hearse. On either side of these shrines and litters walked a large number of Christian young people and clergy from every church in Cochinchina.

The hearse carrying the body of the Bishop was a beautiful litter of about 20 feet in length, carried by 80 picked men, and covered by an embroidered gold canopy. On it was placed the magnificent coffin, covered with beautiful damask, set in a frame and surrounded by 25 large lit candles.

An 1869 photograph of the Pigneau de Béhaine Tomb, commissioned by Nguyễn Phúc Ánh in 1799

The King’s royal guard, comprising more than 12,000 men, was arranged in two lines, with field guns at the head of each line. One hundred and twenty war elephants with their escorts and mahouts walked on both sides. Drums, trumpets and both Annamite and Cambodian military music accompanied the mournful march, which was lit by a prodigious number of candles and torches and more than 2,000 lanterns of different shapes. At least 40,000 men, both Christians and pagans, followed the convoy.

Gia Long was present, along with his mother, his sister, his queen, his children, all the ladies of the court and the mandarins of different government departments. All wanted to express their regret at the eminent and distinguished prelate who was no more, following his remains to the grave which had been prepared to receive him.

Arriving at the grave, the King let a missionary named Father Liot perform the ceremonies of the Catholic liturgy.

The Christian burial ceremony thus completed, Gia Long stepped forward and gave a tearful funeral elegy which he had composed himself. This elegy had been transcribed onto embroidered silk and was presented to the late bishop in the form of a posthumous diploma:

The screen in front of the Pigneau de Béhaine Tomb

“I had a sage, the confidant of my most secret thoughts, who, despite the distance of thousands of miles, came into my kingdom and never left me, even when fortune eluded me.

Why must it be now, at the moment when we are the most united, that this premature and untimely death comes to separate us forever? I talk of Pierre Pigneau, Bishop of Adran, and keeping always in mind the memory of his virtues, I want to give him a new token of my gratitude. I owe it to his rare merits. If in Europe he was known as a man of superior talent, here he was regarded as the most illustrious foreigner ever to appear at the court of Cochinchina.

In my youth, I had the pleasure of meeting this precious friend, whose character fitted so well with mine. When I took my first steps towards the throne of my ancestors, I had him at my side. For me he was a rich treasure, from whom I could draw all the advice I needed to direct me.

But all at once, a thousand misfortunes fell down upon the kingdom, and my feet became as shaky as those of Thieu-khang dynasty of the Ha, so that we had to take a path that separated us as far as heaven from earth. But you, dear master, you embraced our cause with a firm and faithful hand, following the example of four old Hao sages who reinstated the Crown Prince of the Emperor Han-Cao-Te to his rightful status! I confided to you our Crown Prince, when you accepted the mission to go and seek on my behalf the interest of the great monarch who reigned in your country. And you managed to get help for me.

The main shrine inside the Pigneau de Béhaine Tomb

They were already at the half way point when your projects encountered obstacles that prevented them from succeeding. Despite this, you wanted to return to my side, regarding my enemies as yours, to seek the opportunity and the means to combat them. In 1788, when my flag was once more raised over Saigon, I looked forward with impatience to some happy noise announcing your return from France. And in 1790, your boat came floating back onto the waters of Cochinchina. In the skilful and full way of gentleness with which you trained and led the Prince, my son, we saw that heaven had singularly gifted you with the skills of education and youth leadership.

My esteem and affection for you grew day by day. In difficult times, you provided us the means that only you could find. The wisdom of your advice and virtue that shone into the playfulness of your conversation brought us closer and closer, we were such friends and so familiar together that when business called me out of my palace, our horses walked side by side. We never had anything but the same heart.

Since the day when, by happy chance, we met, nothing could alter our friendship, our mutual dedication and boundless confidence that marked our relationship. I hoped that robust health would enable me to continue tasting the sweet fruits of such unity for a long time! But now the dust covers this beautiful tree! What bitter regrets!

To show everyone the great merits of this illustrious foreigner and spread abroad the fragrance of the virtues he always hid under his modesty, I deliver to him the title of Tutor of the Crown Prince, confer on him the dignity and title Quan Công and give him the name Trung Ý. Alas! when the body dies and the soul rises towards the sky, who could keep it chained here? I have finished this short elegy, but my regrets will never end. Oh, beautiful soul of the master! Receive this homage!”

An 1867 image of the Pigneau de Béhaine Tomb, commissioned by Nguyễn Phúc Ánh in 1799

After the funeral oration, the clergy and the Christians withdrew, and the King, alone with the mandarins, offered the customary sacrifices to the spirits of the deceased; afterwards, the King, Prince Cảnh and the ministers each pronounced their own eulogies.

The King had a rich mausoleum built to cover the mortal remains of his faithful guest whose outstanding services he had recognised, and allotted to him a perpetual honour guard of 50 men. This tomb (Cha Cả, as the Annamites call it) survived the persecution [of Catholics and missionaries], protected by the memory of King Gia Long and reverence for the dead, which is one of the virtues of the Annamite people.

After the occupation of the country, France raised the tomb of the most devoted of its children in the Far East to the dignity of a national monument.

Finally in 1814, Gia Long fixed his residence in Huế and was master of all Annam, from Tonkin to Cochinchina. It was Lê Văn Duyệt, the famous conqueror of the port of Thị Nại (Bình Định), who was appointed Governor General of Lower Cochinchina. He lived in Saigon. His official residence was behind the Hoàng Cung (Royal Palace), today Norodom boulevard [Lê Duẩn], almost at the point where the Bishop’s Palace is located. That of his wife was in the Government Palace outside the rampart and the wall of the citadel.

To read Part 2 of this serialisation, click here

To read Part 3 of this serialisation, click here

For other articles relating to Petrus Ky, see:

“A Visit to Petrus-Ky,” from En Indo-Chine 1894-1895

Old Saigon Building of the Week – Petrus Ky Mausoleum and Memorial House, 1937

What Future for Petrus Ky’s Mausoleum and Memorial House?

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.