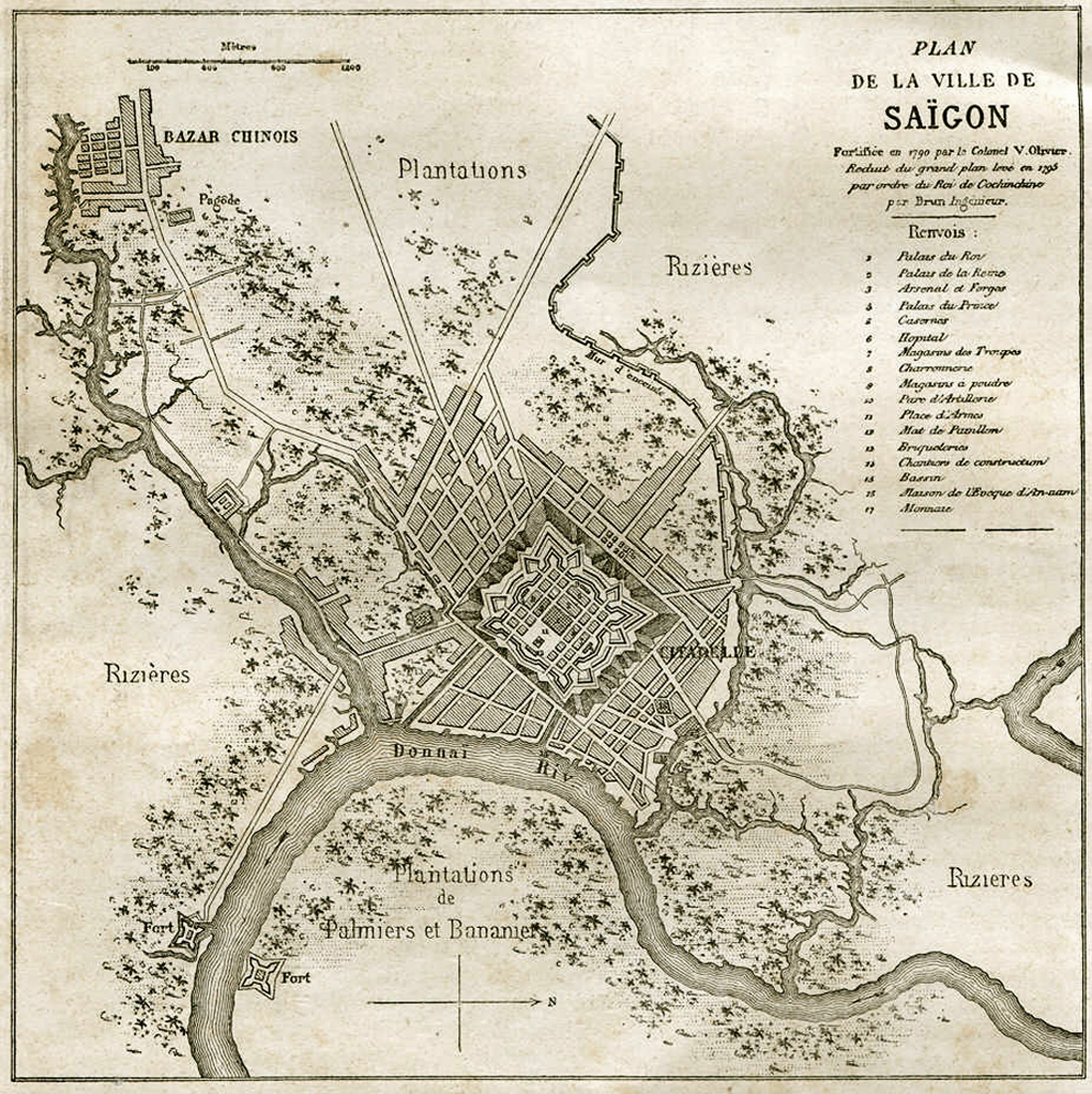

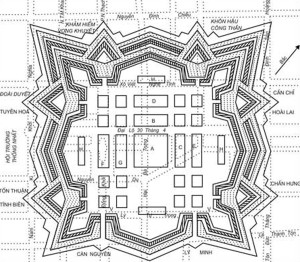

Plan of the city of Saigon, 1790

Published in 1917 by the Saigon municipal government, Notice historique, administrative et politique sur la ville de Saïgon includes this colonial perspective on the history of Saigon.

Writers do not agree on the origins of the name “Saigon.” Some say that the name comes from the two words “Sai,” the Chinese character that means wood, and “Gon,” the Annamite word for cotton. “This name,” wrote Pétrus Ky, “comes from the quantity of cotton which the Cambodians planted around their ancient earthworks, traces of which still remain in the vicinity of the Cay-Mai pagoda.”

A Vietnamese farm outside Saigon

According to others, Saigon is derived from the term “Tai-Ngon,” the name given by Chinese settlers from My-Tho to the city later known as Cholon, which they founded on the arroyo-Chinois in around 1775, when, frightened by the depredations and cruelties of the Tay-Son, they thought it prudent to live closer to the capital “Ben Nghe” (current Saigon), where they would be safer.

Nevertheless, all agree – and we should note this in order to avoid confusion – that until the Franco-Spanish expedition to Cochinchina, the name “Saigon” designated the Chinese city (now Cholon), while the current city of Saigon was known as Ben-Nghe, “after the rach Ben-Nghe which the French named the arroyo-Chinois, having noticed that this arroyo led to the city of Cholon whose most numerous inhabitants were Chinese traders.” (Pétrus Ky).

The name Ben Nghe-applied to the area between the arroyo-de-l’Avalanche [Thị Nghè creek], the Saigon river and the current arroyo-Chinois [Bến Nghé creek]. It was also called Gia-Dinh, a name which, by extension, also served for a time to designate the entire eastern part of Lower Cochinchina.

Pétrus Ký

According to Pétrus Ky, before the reign of Gia-Long, Saigon was nothing more than a Cambodian village. However, it must have been quite an important centre, for history relates that towards the end of the 17th century, and during the course of the 18th century, it was the residence of the Second King of Cambodia.

Indeed, until 1684, Lower Cochinchina, which was part of the Khmer kingdom, was governed by its second king, while the first king resided in Udong, which had become the capital of the kingdom.

At that time, civil war broke out in Lower Cochinchina. The king of Annam, at the request of the second king of Cambodia, who, as we have said, lived in Ben-Nghe (Saigon), became the arbiter of the dispute between the Cambodian sovereign and the Chinese settlers in My-Tho and Bien-Hoa. He dispatched to the area the Annamite Governor of Khanh-Hoa, who, after defeating the Chinese at My-Tho, concluded a treaty with the king of Cambodia. However, when the latter was unfaithful to the treaty, the king of Hue sent the mandarin Nguyen-Huu-Hao to Lower Cochinchina to bring him to justice.

The campaign did not last long. The first king of Cambodia was taken prisoner and died shortly after his arrival in Saigon. The second king, gripped by fear, killed himself.

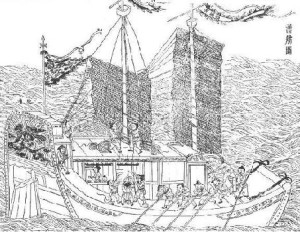

A two-masted Chinese junk, from the Tiangong Kaiwu of Song Yingxing (1637)

Before his death, the king of Cambodia had to accept the overlordship of the court of Hue, and also lost his nominal sovereignty over Lower Cochinchina, which was later (1689) definitively taken from him.

In the meantime, eager to escape the Manchu domination, three Chinese generals of the imperial Ming army, followed by several thousand soldiers, asked to settle in Cochinchina in order to exploit its vast uncultivated lands. In fact, they came with the approval of the court of Hue, with the hidden intention to conquer the country on behalf of the king of Annam. They settled in the provinces of Bien-Hoa and My-Tho, where they wasted no time driving out the indigenous population in concert with the Annamite infiltrators. Another Chinese, the adventurer Mac Cuu, seized the country of Ha-Tien, simultaneously paying homage to the emperor of Annam.

Thus was formed the Annamite colony of Lower Cochinchina, its population bolstered by the mass transportation of all the vagabonds of the kingdom. At the head of its administration was placed a kinh-luoc (viceroy), who established his residence in Ben-Nghe (Saigon), from which the Cambodian community were expelled.

Pigneau de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran

During the Tay-Son war, Saigon was taken and retaken several times, sometimes by Nguyen-Anh, legitimate heir of the Nguyen, and sometimes by the Tay-Son. Eventually, thanks to the support of Bishop Pigneau de Béhaine and the brave French officers who came after him, the chua (lord) of Cochinchina could definitively chase out the usurpers and consolidate his power over all of Lower Cochinchina (1790).

Nguyen-Anh – who later proclaimed himself emperor of Annam under the name Gia-Long – chose Saigon as his imperial residence until 1811, when he left to settle in Hue, leaving as governor of Cochinchina the ta-quan (left marshal) Lè-Van-Duyet, a grand dignitary of the court of Annam, known to history as the “great eunuch.” It was also in Saigon that Le-Van-Duyet established his residence.

Saigon under Gia-Long

“The city was laid out and fortified in 1790 by Colonel Victor Olivier. It stretched, as today, from the right bank of the river, between the rach Ben-Nghe and the rach Thi-Nghe (which we named the arroyo-Chinois and the arroyo-de-l’Avalanche). Laid out regularly, there were over forty straight roads, 15 to 20 metres wide and generally perpendicular or parallel to the riverbank. Two canals advanced into the heart of the city, and naturally, there were some wetlands, particularly in the terrain which later became rue de Canton, and also between the old route de Cholon and the arroyo-Chinois (the marais Boresse).

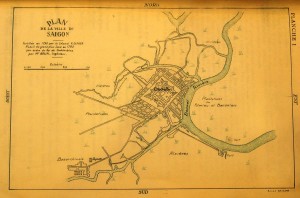

Plan of Saigon, 1793

In the centre was the citadel, a huge square bastion with a perimeter of 2,500 metres. Access was gained through two gates on each side, and the main axis of the structure was in line with the present-day road leading to the Third Avalanche bridge, the rue Paul Blanchy [Hai Bà Trưng].

The citadel walls enclosed many buildings. In the middle was the royal palace, and in front of that were the military parade ground and the field artillery park. A monumental flagpole stood in the centre of the bastion, looking out towards the river. On the left of the royal palace was the residence of the crown prince. At its rear was the residence of the queen. On the right of the royal palace were the arsenal, the forges and ten workshop buildings. The bastions at the centre of the northeast, northwest and southwest faces contained the powder magazines. Between the residence of the queen and the northwest powder magazine was the hospital. On the left, behind the royal palace and the residence of the crown prince, were the army stores (nine buildings).

With its ramparts, ditches and glacis [earthen banks], the citadel covered an area of about 65 hectares; moreover, on the northwest side, at the foot of the glacis, were barracks, straddling the road to the Third Avalanche bridge [the Kiệu bridge].

Plan of the 1790 citadel

The city itself was also encircled by a fortified wall – probably an earthen embankment – with forts at regular intervals. Facing the Plain of Tombs, it ran from the Second Avalanche bridge [the Bông bridge], following the right bank of the river and then heading west, intersecting the route de Thuan-Kieu and continuing to Cholon.

Down river from Saigon, on both banks, stood strong bastions which we called the “fort du Sud” (on the right bank), and the “fort du Nord” (on the left bank) – the second more important than the first – which defended the approaches to the city.

On the bank of the arroyo-de-l’Avalanche, before reaching the First Avalanche bridge [Thị Nghè bridge], were the shipbuilding yards. It was lower down from here, on the Saigon river, that after our arrival we set up the naval barracks and artillery. Among the workshops on the arroyo-de-l’Avalanche we installed a dry dock.

Towards the location of the current central prison was the royal treasury. It was on the site of the royal brick kilns that we built our market, which will soon be abandoned. The food stores were in Cho-Quan.

The Pigneau de Béhaine mausoleum, demolished in 1983

Since we are trying to describe the Saigon of Gia-Long and Victor Ollivier – the Saigon which saw the uprising of Khoi and the subsequent destruction by Minh Mang, just a dozen years after the death of Gia-Long – we may be permitted to add a few more interesting details for those who are concerned about the past of our Indochina.

This Gia-Dinh (Saigon) had about 50,000 souls, living in forty villages or hamlets clustered around the citadel, in the territory that extended as far as Cholon (big market). Between the northeast face of the Citadel and the arroyo-de-l’Avalanche there was a community of native Christians, clustered around the house of the bishop of Adran; this community was located around 200 metres beyond the glacis, not far from the land on which our first general food stores were later built. It was to here in 1799 that the coffin of Pigneau de Béhaine was brought to be placed on view, and it was from here that the funeral procession, with Gia-Long at its head, processed along the northeast and northwest sides of the citadel to the place of burial, now the national monument that we all know [see Lăng Cha Cả – from mausoleum…. to roundabout!].

Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt

After the recapture of Saigon by the troops of Minh-Mang, the Christian community and the house of the Bishop of Adran were destroyed and the Christians were driven across to the left bank of rach Thi-Nghe, where there is now a hospital of the Sisters of the Sainte-Enfance.” (Extract from Revue Indochinoise: “l’Insurrection de Giadinh,” by M J Silvestre).

Saigon under Minh-Mang, Thieu-Tri and Tu-Duc

On the death of Gia Long (1820). Le-Van-Duyet, who was then still the governor general of Lower Cochinchina, went to Hue for the coronation celebrations. Minh Mang thought to get rid of Le-Van-Duyet because his actions thwarted the accomplishment of the king’s designs, and especially because he knew Le-Van-Duyet to be favourable to the French and the Christians. Having failed in his criminal enterprise, he let him go back to Saigon. But when he learned of his death, the Emperor abolished his charge and divided Lower Cochinchina into six provinces, with as many Governors. That of Saigon (Gia-Dinh) instituted a court under the king’s presidency for the posthumous trial of the deceased.

This outrage deeply wounded the officers of the old marshal. In addition, the governor of Gia-Dinh accused one of those officers, Pho-Ve-Huy (Lieutenant Colonel) Le-Huu-Khoi, of having exploited the forests for his own use, and demoted him. This was the signal for revolt.

King Minh Mạng

Minh-Mang sent troops by land and sea to fight the rebellion, and on 8 September 1835, the imperial army took by storm the citadel of Saigon, where the besieged were entrenched. The repression was terrible. More than a thousand people were massacred, with the exception of the five main leaders and the French missionary Father Marchand, who, found in the citadel, was considered to be an accomplice of the rebels.

These six prisoners were locked in cages and sent to Hue, where they were tried. After enduring torture, they were sentenced to the “execution of one hundred cuts.”

“The taking of the citadel of Gia Long, called Phan-Yen, had been very difficult and the siege had lasted two years. Afterwards it was razed to the ground by order of Minh Mang, and in its place was built the fortress of lesser dimensions which we captured when we took Saigon in 1859.

In 1879, one could still see the remains of ditches behind the old Camp des lettrés, close to the rue Chasseloup-Laubat, and by marking the location of these half-filled ditches, one could trace the footprint of Gia-Long’s huge 1790 citadel. One of its faces, starting from a point located to the northeast of the Pagode Barbé and descending southeastward to the residence of the Director of Engineering, measured approximately 900 metres in a straight line. The northwest bastion extended outwards from the spot which today forms the intersection of rue Chasseloup-Laubat [Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai] and rue Pellerin [Pasteur].

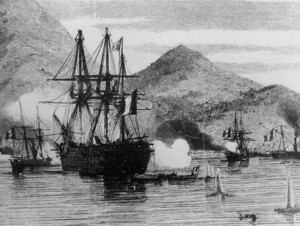

The Franco-Spanish fleet in Tourane, 1859

During the construction of the Saigon Cathedral, we had to remove a considerable amount of rubble to lay the foundations for that monument, and when we did so, we discovered a layer of ash and charred debris, thirty centimetres thick. This was probably the remains of Khoi’s supplies stores, burned to the ground when the citadel fell. Amongst this debris, we found masses of copper coins, welded together by the heat, plus large quantities of iron and stone cannon balls, as well as the bodies of children buried in sealed jars. In fact, the Cathedral site is located in the area between the south and west bastions of the ancient citadel, close to the southwest face.” (M J Silvestre).

Saigon from conquest to the present day

Under the Emperors Minh-Mang, Thieu-Tri and Tu-Duc, foreigners were systematically rebuffed and Christians persecuted. “After the murder of Spanish bishop Monsignor Diaz and the outrageous reception prepared for the French ship Catinat in the Bay of Tourane, France and Spain decided to act in a forceful way.” (Géographie générale de l’Indochine by P. Alinot).

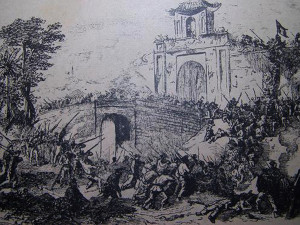

The capture of the second Gia Định Citadel in 1859

An expedition entrusted to Admiral Rigault de Genouilly was sent to Cochinchina (1857). After occupying Tourane (1858), the Admiral, at the head of a naval division, went to Lower Cochinchina and arrived on 15 February 1859 in the city of Saigon. The citadel, which was taken on 17 February, gave us possession of considerable matériel.

The following 1 November, Admiral de Genouilly, recalled to France at his own request, was replaced by Rear Admiral Page. Sent shortly after to China, he left in Saigon a garrison of 800 men, including 200 Spanish Tagals and a small fleet of two corvettes and four sloops. The command was given to Captain Ariès, supported by Spanish Colonel Palanca Guittierez.

The Annamites, profiting from our numerical weakness, tried by incessant skirmishes to tire the expeditionary force. It was besieged in Saigon and not until the end of the China campaign could we resume operations with vigour.

Vice Admiral Charner arrived in Saigon on 7 February 1861, and a few days later, after brilliant feats of arms by his soldiers, he took the famous “Lines of Ky-Hoa,” where the Annamites had been entrenched.

The capture of the “Lines of Ky-Hoa” in 1862

The siege of Saigon finally raised, we could devote attention to the organisation of the conquest.

“The retail trade and the mooring of large junks gave a certain significance to our Saigon: many shops were established in Ben-Nghe and in Cho-Moi. At that time, along the banks of the Saigon river and the arroyo-Chinois, there existed two long streets lined with houses with tiled roofs. Today these buildings have disappeared and the country certainly has no reason to complain. We made a clean sweep of the old town and its location. Everything has changed: we levelled heights and filled ponds, dug canals, and replaced the waterside huts with large forty metre quays. European houses gradually succeeded the old Annamite huts. Today, the beautiful trees planted along our main streets make us forget the verdant groves of areca which were slaughtered for the purpose of building and sanitation. Soon, iron bridges will replace the old wooden ones.

Saigon port in the early 20th century

Although only five years separate us from the era when this transformation began, it would be very difficult today, even for those who have not left the colony since 1861, to find traces of the ancient city, to recognise the terrain and to replicate exactly the original look of the place.” (M H Blaquière, writing in the Courrier Saigonnais on 20 January 1868).

These lines were written, nearly fifty years ago. How many more changes have taken place since then?

M H Blaquière continues: “Fifty years ago, the Saigon area was a muddy plain, crossed by meandering arroyos, the natural result of the Boresse marsh, and dominated by an Annamite citadel enclosed by walls of earth and foul ditches.”

“Today,” add the Annales coloniales, “Saigon is the ‘Pearl of the Far East,’ with many roads leading to other pretty towns such as Bien-Hoa, Cholon, My-Tho, Baria, etc. If we take into account the relatively short time of our occupation compared to the neighbouring British colonies which date back more than a century, or the Dutch colonies which have already celebrated their tercentenary, one will be amazed at the progress that our ancestors have achieved in a region once so unhealthy, where every task was the task of Titan.”

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.