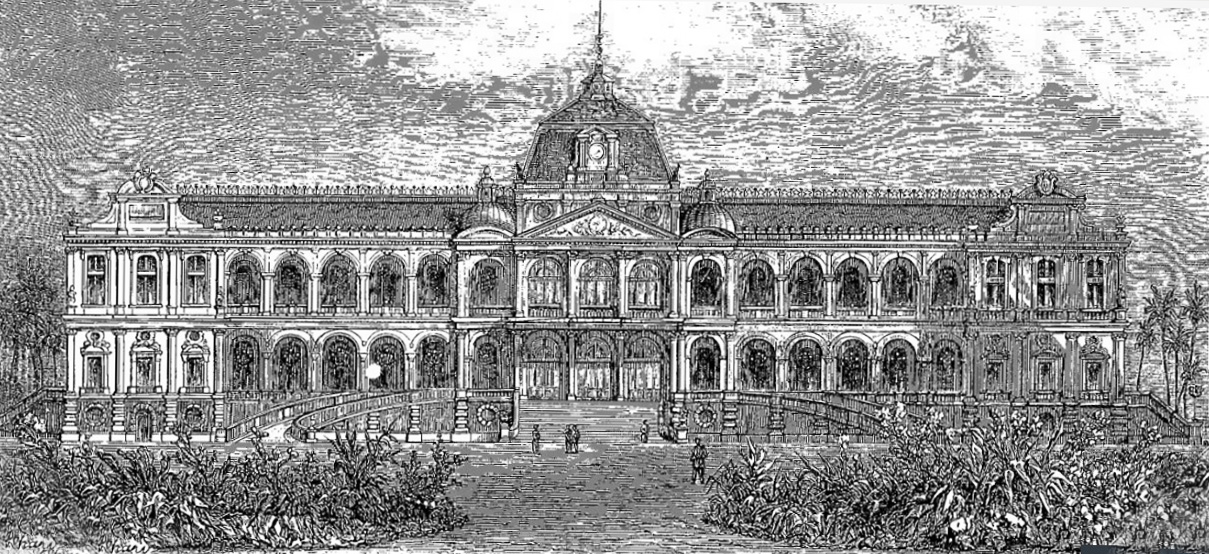

Hermitte’s Palace of the Government (1873)

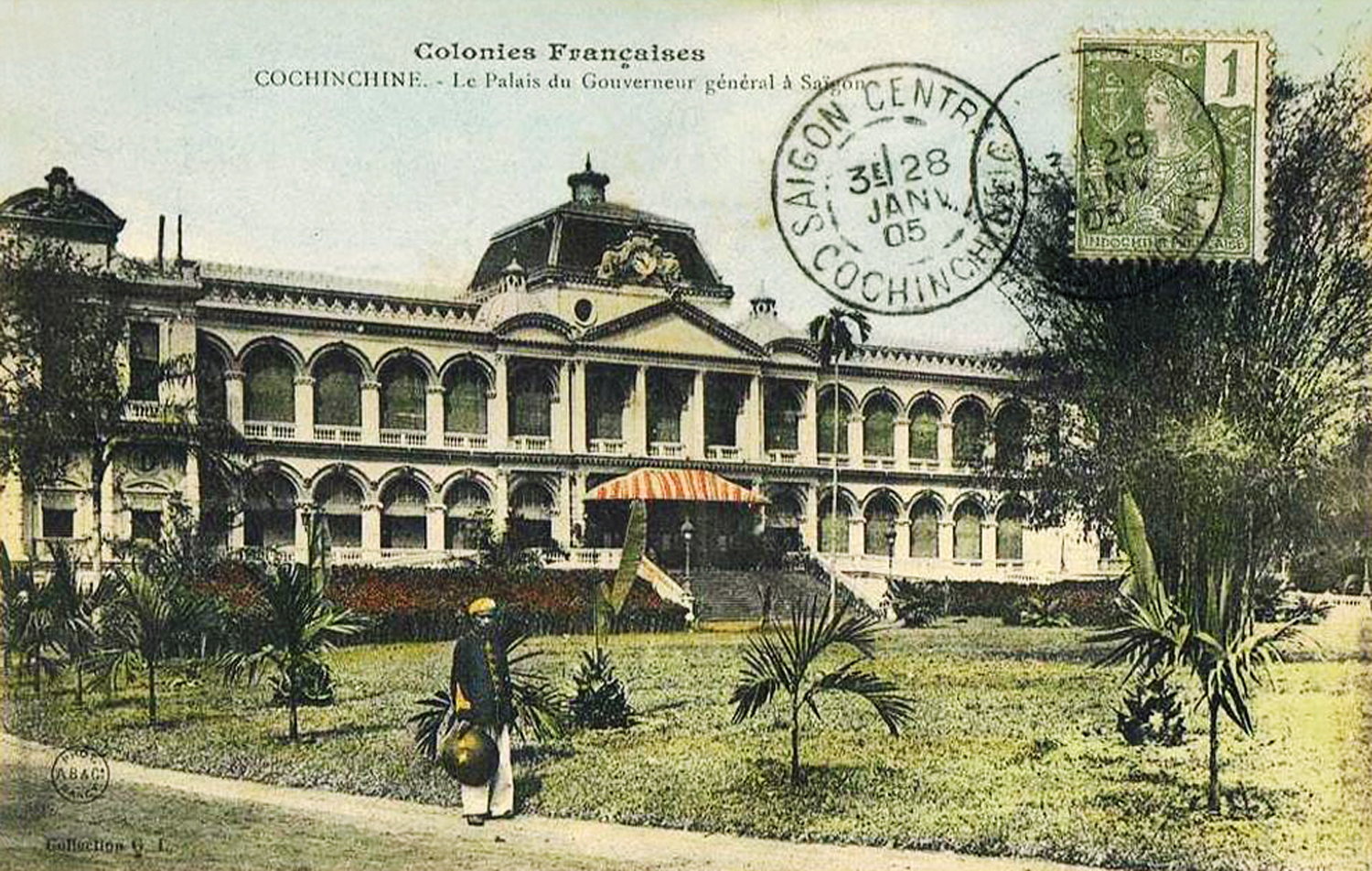

Parisian architect Achille-Antoine Hermitte (1840-1870) was responsible for the Sacred Heart Cathedral in Guangzhou (1866) and the first Hong Kong Town Hall (1869) before he designed his best-known work, the Palace of the Government (later Norodom Palace) in Saigon.

A spiritual correspondent of the Tour du Monde once said: “Cochinchina is to China what Belgium is to France,” and with these words we could well enough grasp what we might expect to meet in our new colony, which is neighbour to a state with no less than 35 million inhabitants of different nationalities. It will be easy to understand the importance of our new possessions when we say that the total area of the French provinces in Cochinchina is 22,380 square kilometres, out of which the province of Saigon accounts for 1,500 square meters.

The city of Saigon, fallen to the power of Admiral Rigault de Genouilly on 17 February 1859, is built 55 kilometres from the sea. It is located at 104° 21′ 43″ longitude east and 10° 46′ 40″ latitude north. A few years ago, it was not less than seven kilometres in length by five kilometres wide. The largest part of the population was made up of 20,000 Asians.

Here is what was written in 1866 about the capital of our new colony:

“Saigon previously formed an agglomeration of more than 40 villages, representing a population of at least 50,000 souls. At the start of our expedition of conquest, all of these villages, with the exception of one – Cho-Quan – were destroyed by the enemy, who wanted to leave us only ruins. Since that time, 11 other villages have been formed around us and under our protection. These 12 villages have 830 registered inhabitants, who represent a total of approximately 8,000 souls. ¹

As for the European city, which contains the citadel, the governor’s residence, the offices of the administration, the barracks, the military hospital, the church, the arsenal, etc, it is enclosed between the river to the east, the arroyo ² Chinois to the south, the arroyo de l’Avalanche to the north, and the territories conceded to Annamite villages to the south-west. On 1 January 1865, its population included 557 Europeans, 600 Malabars and 12,000 Chinese, not counting the troops of the garrison and the crews of the ships and boats in the harbour.

Early colonial Saigon

The plan of Saigon, drawn up on 10 May 1862, has been executed in large part. We have laid out and paved numerous wide streets amounting to 30 kilometres in length, opened or deepened canals, built bridges and quays, filled swamps, built a church, a hospital, and stone houses; and constructed a 53 metre long by 4 metre deep dry dock; Finally, we have also installed a floating dock which will receive ships of the highest tonnage.”

These lines were written at the most five years ago, and one only has to consult the excellent Annuaire de la Cochinchine ³, just published in Saigon under the administration of the excellent Rear-Admiral Dupré, to get an exact idea of the progressive improvements which have succeeded one after another since that time. Notable buildings of more than one kind have been constructed in the European city, and, what’s more, essential institutions have been founded there, including hospitals, asylums, and schools where young natives are eagerly received. It will give a fair idea of what the latter institutions may produce in future when it is known that 19 schools are now in full operation, teaching no fewer than 790 students.

This number is eloquent, no doubt, but many others could easily be listed here which would attest to the solid hopes of our colony. In order to offer some, even without commentary, to the reader’s meditations, we will recall that from 1 January 1870 to 1 January 1871, 551 ships entered the port of Saigon, while 554 left.

Here we ignore cabotage, a sector now more active than ever, and agricultural labour, the detail of which we spare the reader, saying only that for the year 1869 it produced for the administration receipts of 8,322,559 francs 19 cents, although there was a slight decrease in 1870, which only offered the figure of 8,053,689 francs 10 cents. An unofficial account suggests that the revenue from 1871 will reach 9,500,000 francs, but new information suggests that the final figure may be as much as 12 million francs. Rice exportation this year will amount to 350,000 tonnes and will employ more than 600 ships, including some very large ones. This export represents a sum of 90 million francs. One sees all that one can expect from so recent an acquisition.

Perhaps the reader is wondering why such emphasis on these figures in an article about a monument. In fact, they serve to help people understand the importance attached to certain buildings, especially those which aim to impress the Asian population with their imposing mass.

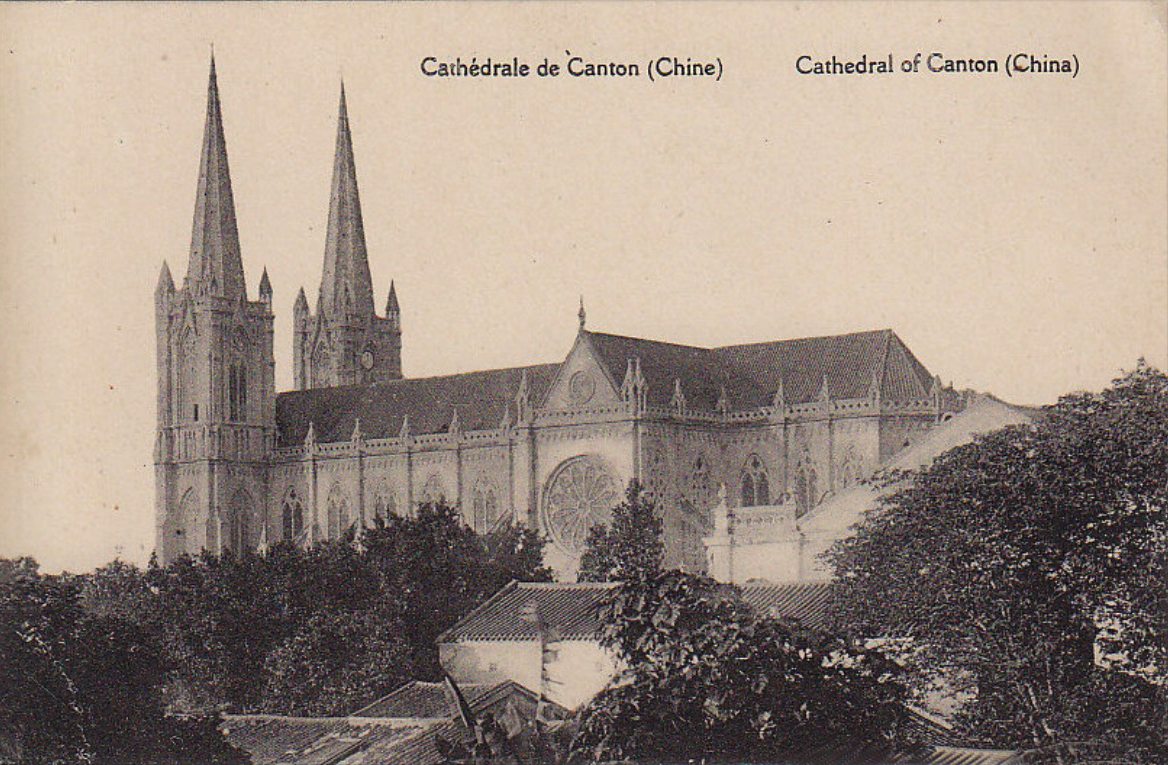

Hermitte’s Sacred Heart Cathedral in Guangzhou (1866)

It was on 23 February 1868, that Vice-Admiral de la Grandière, Governor and commander in chief of the colony, laid the first stone of the new palace. For the young architect, M. Hermitte, who had drawn up the plan, this was not his first attempt. Having arrived early in the country of Annam, and then settled in China, he began his work at Canton with the construction of the vast granite cathedral, the completion of which will require perhaps many years. Having lost as a result of war the buildings which he had acquired, the unhappy artist abandoned his labours there and took refuge in Cochinchina. It was here that his too short career would end; he died here in 1870. M. Codry succeeded him.

Preoccupied no doubt by memories of his native land, the architect of the Palace of the Government in Saigon did not show much originality in his original conception. It is curious, however, that at the moment when a dreadful fire deprived Paris of the edifice conceived by Philippe Delorme, a rather faithful image of the Tuileries took shape at the extremity of the Asiatic world.

The Palace of the Government of French Cochinchina stands at the corner of the route de Cholon and the boulevard de Saigon. It has not less than 80 metres of facade, and is placed in the middle of a rectangle which extends 450 metres on one of its sides and 300 metres on the other. Eight main roads extend outward from the road which encircles the palace and its park.

The Annuaire we have just mentioned says nothing about the new building; Nonetheless there is a sentence which sufficiently explains the extent of territory which will be governed from this vast edifice.

“Custom has preserved in French Cochinchina the division of the provinces as they existed under the Annamite regime; But this denomination no longer employs any special administration in each province. The administration now emanates entirely from Saigon.”

Hermitte’s Hong Kong Town Hall (1869)

Neither should it be forgotten that if the European population of our colony increased three years ago to 585 inhabitants, that of the Asians amounted to 1,183,913 individuals of both sexes, requiring extensive administrative provision.

The palace, with its large reception room and offices, had to be built to large proportions. We know from recent news that gardens are now being planted. The exact surface of the park is 13 hectares.

A large cistern, destined to supply the palace daily with 500 litres of water free of impurities, is being dug by the hour. The question now is whether to create a large lawn or a water feature in the space between the main entrance and the front steps. That space is not less than 200 metres in length.

Footnotes

¹ As an official source, see the Notices sur les colonies françaises (1866), p. 539. We shall also indicate, for the benefit of those who wish to have general notions of the empire of Annam, some works recently published, such as the following books: Tableau de la Cochinchine, written under the auspices of the Société d’ethnographie by Messrs E. Cortambert and L. de Rosny; L de Grammont’s Onze mois de sous-prefecture en basse Cochinchine, 1863; Les Ports de l’extrême Orient, 1869, by Dr. A. Benoit de la Grandière; Cochinchine Française by Charles Lemire, 1869; Dialogues Cochinchinois, published in 1871, with an indication of the weights and measures and divisions of time by M. Abel des Michels, professor at the college du France; and finally M. Barbié du Bocage’s Bibliographie Annamite of 1867.

² This Spanish and Portuguese word is used to describe a small waterway

³ Annuaire pour la Cochinchine française, Imprimerie nationale, Saigon, 1871. This precious work is aimed at Europeans, natives and Chinese. The divisions of time are marked according to the calculations adopted by the three races.

Hermitte’s Palace of the Government (1873)

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now and Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.