Prince Nguyễn Phúc Bửu Lân, the former Emperor Thành Thái

Following his La Réunion interview with the exiled Prince Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh San (the former Emperor Duy Tân), An Emperor of Annam in La Réunion, published in the Écho annamite newspaper on 7 March, Charles Wattebled went searching for Prince Vĩnh San’s reclusive father Prince Nguyễn Phúc Bửu Lân (the former Emperor Thành Thái), who had also been exiled on the same island. The following article by Marcel [sic] Wattebled, published in the Écho annamite on 9 March, is translated below, along with a critical editorial published in the same newspaper a week later.

If, by his affable manners, distinction and friendliness, Prince Vinh-San has attracted the sympathies of the elite of the Bourbon population, his uncle [sic], the former Emperor Thanh-Thai, who calls himself Prince Buu-Lan, on the contrary does not enjoy the same popularity on the island of La Réunion. He lives, moreover, in the fiercest retirement.

The race course in St-Denis, La Réunion

He stands accused of some acts of cruelty that I cannot mention here; I will simply quote to you the latest: being the owner of a pretty Australian mare named Crémone which he trained himself, he one day, in a fit of rage after it lost a race, put out its eye with a crack of his whip.

When I presented myself at the address which had been given to me, no-one seemed to know about him.

Seeing on the street corner an attractive dark-haired lady with gleaming white teeth smiling behind her stand full of juicy mangoes, perfumed bananas and stinking jackfruit slices, I asked her:

“Can you tell me, dear child, where is the home of Prince Buu-Lan?”

“Who that? Who Prince Buu Lan?” she replied in a sing-song voice, “Me not know.”

Then, after reflecting for a moment:

“Ah! Maybe you look for “Chinese king?”

“Yes, that’s him, the “Chinese king.”

“Oh! Me not know! But his house not in rue St-Denis. His house in rue Ste-Anne, tenth door along.”

A street in St-Denis, La Réunion

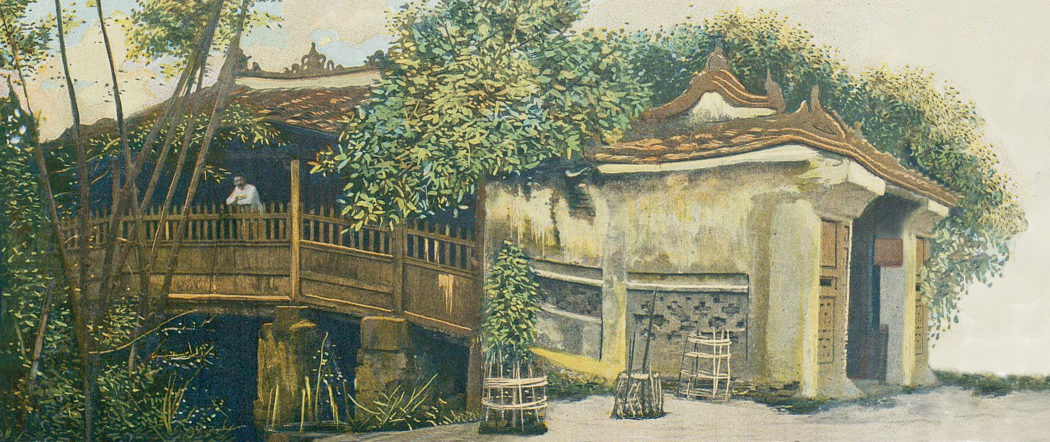

Passing through the latticework gate to which I had been directed by that lady, I saw, in the shade of a large mango tree and surrounded by beautiful rose bushes, a wooden house of humble appearance.

No one answered my call, so I opened the door. In the middle of an unfurnished anti-chamber swarmed a dozen Annamite boys, some naked, others dressed in a short tunics; they fixed their great fearful eyes on me, not understanding any of my questions.

Just then, a nice girl with a bright expression arrived and stared inquisitively at me with her pretty eyes.

“Please can you tell me, where is your father, Prince Buu-Lan? I wish to see him.”

“No, me not know where he go.”

And raising a fine and graceful hand, the daughter of Thanh-Thai beckoned to me that he had gone very far.

“I will return later,” I told her, and went out, while the servants, still looking frightened, made a gesture to see out the “makoui” who had dared to enter the house.

Out of spite, I placed my camera in position in order to take a photograph. Even if I could not take a picture of the “Chinese King,” I thought, I can at least take one of his house. Then suddenly, as a strong breeze began to blow through the large clumps of flowers, sending out puffs of fragrant air, a voice came from neighbouring house:

La Réunion

“Here he comes, the Chinese King!”

Turning, I saw at the bend in the street a small, stocky man, wearing a khaki suit and a grey hat. He had the peaceful demeanour of a good bourgeois returning from market; the basket which he held on his arm was full of fruit, preserves and Chinese joss sticks. At his side walked a very pretty Annamite woman who very gracefully wore a long and richly-decorated black lace tunic over broad white silk trousers. As soon as he approached, I noticed that his dark glasses concealed a kind of exotropia [a form of eye misalignment in which one or both of the eyes turn outward]; his look was very hard, his lips tightly pinched.

Politely I approached him, but I had hardly mentioned the word photography when he replied abruptly:

“You are wrong! I am not the king of Annam!”

“I know you are no longer king.”

A passer-by, hearing this strange conversation, turned and looked at us with a disturbed air.

Due perhaps to his pride at being caught in humble attire, or even because he wanted his life to remain mysterious, the “Chinese king” – because it was, indeed, he who did not want his picture to be published, at least in his present state devoid of ceremonial costume – replied gruffly:

“You should not surprise people like this. If you wish to see me, come back in the afternoon.”

Prince Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh San, the former Emperor Duy Tân, pictured at his house in St-Denis, La Réunion

“Alas, I cannot. I must return to the port earlier to board the Dumbea. Your nephew [sic], Prince Vinh-San, understood this; he very kindly posed for my camera this morning.”

“Oh, him, that’s all he wants; but me … I’m not the same.”

However, when I presented my card – made from a fine strip of Japanese wood and adorned with a beautiful Japanese landscape – his arrogance dissipated.

“Your card comes from Japan!” he said in surprise. “So you know that country?”

“Yes, for nearly 20 years, and I like it very much. You also?”

“Oh! I have travelled from north to south; I know the big cities; Tokyo, Kyoto, Kobe. I spent three years in Japan as a cavalry captain!”

And we embarked upon an exchange of impressions of Japan, recalling shared memories.

“Well!” He said finally in a softened tone, “As you cannot return later, and because I do not want to let you go away empty-handed, wait a moment. I’ll give you my portrait.”

And, a few moments later, inside his house, he gave me a photograph of him dressed in Annamite costume, with the Légion d’honneur around his-neck.

And we parted good friends.

The Hôtel de ville in St-Denis, La Réunion

I had hoped that during this conversation, the friend who had accompanied me would hasten to photograph the scene, but he told me as we left that, suddenly captivated by the fresh beauty and bewitching eyes of the “Chinese Queen,” he did not give one thought to operating the shutter of the camera.

And that is why I cannot show you today the image of the house of the former Emperor Thanh Thai!

Marcel Wattebled

Editorial, 16 March 1927: Their Majesties Thành-Thai and Duy-Tan – A word about the errors of Monsieur Wattebled.

However, when I presented my card – made from a fine strip of Japanese wood and adorned with a beautiful Japanese landscape – his arrogance dissipated.

“Your card comes from Japan!” he said in surprise. “So you know that country?”

“Yes, for nearly 20 years, and I like it very much. You also?”

“Oh! I have travelled from north to south; I know the big cities; Tokyo, Kyoto, Kobe. I spent three years in Japan as a cavalry captain!”

And we embarked upon an exchange of impressions of Japan, recalling shared memories.

A view of St-Denis, La Réunion

This passage is taken from the article by Monsieur Marcel Wattebled (whose first name was Charles when he signed his previous interview with the former Emperor Duy Tan, perhaps he has two first names, and uses each in turn according to his preference?) when he shared with us his interview with the “Chinese king.”

These lines could be cited as a model of fantasy reporting, and at the very least we may say that the subject’s comments about Japan were only uttered to mystify the interviewer, a caprice which would hardly be surprising from Thanh-Thai, from whom we know of other exploits of a similar kind.

We have said that which needed to be said in the “Premier-Saigon” column of the Écho Annamite last Saturday.

In fact, the “Chinese king” has never set foot in the land of the Rising Sun; this being the strongest reason why he has never served the Mikado as a cavalry captain.

Certainly, Thanh-Thai could not have served in such a capacity before ascending the throne, that is to say before he reached the age of 10 years!

Furthermore, he could not have done so after his accession. Khai-Dinh was the first king of Annam “in office” to venture outside his kingdom, in order to attend the famous parade at the Exposition coloniale in Marseille in 1922, and this deviation from the ancient traditions earned him many critics, whether justified or not – though we do not have to discuss it here.

Revolutionary Prince Cường Để (Nguyễn Phúc Đan), who went to Japan in 1905

As to the idea that Thanh-Thai stayed in Japan after his forced abdication, and above all that he was recruited, in any capacity, into the Japanese army, nothing could be more absurd, because we may understand perfectly that the French government would, in all of its authority, have opposed and prevented it.

Probably Thanh-Thai knew some information about the country of chrysanthemums, either through reading or through the epistolary relations he would have had with Prince Cuong-De, who himself acquired there over a period of many years, information that the former emperor could have called upon cleverly in order to give an air of reality to his imaginary stay in that archipelago. An archipelago which is visited, with tragic regularity, by earthquakes!

Anyway, we will admit, until proven otherwise, to the documentary value of Monsieur Wattebled’s reports, originally published by our local sister paper l’Opinion, about the lives led by the exiled Annamite princes, and that is why we have reproduced them in our newspaper.

All the same, it is surprising that almost all of the information contained in the above report is of such an inexactitude such that some people might be tempted to place all of Monsieur Wattebled’s articles in the same boat, leading therefore to a loss of authority, because of their questionable nature.

The following extract from his interview with Prince Vinh-San, is no exception to the rule – if necessary, one may call it a “rule of error” or “rule of fantasy.” In it, he recounts many incontestable truths amongst the inaccuracies regarding that which is commonly known as the Hue conspiracy of 1916.

It’s the ex-emperor Duy-Tan speaking, at least Monsieur Wattebled related his words directly:

Prince Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh San, the former Emperor Duy Tân, pictured at his house in St-Denis, La Réunion

“After occupying the throne of Annam from 1907 to 1916, the best years of my life, I was one day misguided by some members of the ‘Young Annam’ party, who wanted me to lead a revolutionary movement. I fled the palace of Hue on the night of 3 May 1916 to join the conspirators. My flight was quickly discovered. Four days later, remorseful, I went to see Messieurs Le Fol and Saunier, who led me to the Resident-Superior, Monsieur Charles.”

“After occupying the throne of Annam” – this would suggest that Duy-Tan was no longer emperor on the outbreak of the 1916 affair in which he was involved.

In reality, Duy-Tan was still emperor when the plot was discovered; and it was under that title that he participated in it, giving it a meaning which was much more severe, and also of increased gravity; his gesture was dictated neither by the spite of having lost the crown, nor by the ambition to win it back.

“Four days later,” we read again, “remorseful, I went to see Messieurs Le Fol and Saunier.”

The truth is that, after the discovery of his retreat – a pagoda near Hue – Duy-Tan was arrested. A Tonkin newspaper even reported this response by His Majesty to someone who asked him if he was armed: “Do you think if I was armed I would let you talk to me in this way without punishing you for your insolence?” This reply is far, I would suggest, from a reflection of any remorse, and is entirely consistent with Duy-Tan’s pride of character, which was well known at that time. In addition, it indicates that if the young king was taken to Messrs Le Fol and Saunier, this was certainly not of his own accord.

But the 1916 uprising attempt deserves to be known in more detail, if only for historical interest. The articles of Monsieur Wattebled do, at least, have the merit of providing us with the opportunity to begin to tackle a task which has long tempted us.

E. Dejean de la Batie

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group page Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.