This article was published previously in Saigoneer http://saigoneer.com

As traffic congestion and air pollution intensifies, Hồ Chí Minh City’s urban greenbelt has assumed increased significance as the “green lung” which helps to disperse pollutants, check the flow of dust and reduce noise levels. What better time to pay tribute to Jean-Baptiste Louis-Pierre, the Frenchman who was responsible not only for the city’s famous Botanical and Zoological Gardens, but also for many of its parks and tree-lined boulevards.

Jean-Baptiste Louis-Pierre (1833-1905)

Born on 23 October 1833 into a rich sugar planter family in Saint André on the island of La Réunion, Pierre went on to study medicine in Paris and then specialised in botany in Strasbourg. But when his family lost everything in the early 1850s “from the combined effects of a devastating hurricane and losses incurred as a result of the enfranchisement of their slaves,” Pierre cut short his research to take up a post with the British Imperial Forestry Service in Calcutta under Sir Dietrich Brandis, the “father of tropical forestry.” Rising quickly through the ranks of the British colonial service, he subsequently became Head of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens.

It was Pierre’s reputation as a skilled botanist which in 1865 brought him to the attention of French Naval Ministry officers in Saigon. In the previous year, Rear Admiral Pierre-Paul de La Grandière, Governor of Cochinchina, had commissioned a French army veterinarian named Rodolphe Alphonse Germain to set up the Jardin botanique et zoologique de Saïgon, on 12 hectares of land close to the arroyo de l’Avalanche (Thị Nghè Creek).

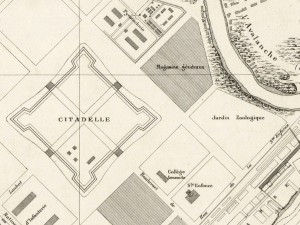

The Jardin botanique et zoologique de Saïgon pictured on an 1864 map of Saigon

The function of the new institution was primarily to research and develop plant and animal species for economic purposes, and to this end the Jardin incorporated several animal breeding pens, as well as greenhouses to cultivate seedlings for research. However, the Colonial Council quickly realised that its further development would be contingent on professional input, so on 28 March 1865 they appointed Pierre as its first Director. Later that year, he was also named as a member of the Cochinchina Agricultural and Industrial Committee.

A botanist who dedicated his life to the cause of science, Pierre held the post of Director of the Jardin botanique et zoologique until 1877, developing its infrastructure and shipping in many rare animal, plant and tree species from India and nearby Laos, Cambodia and Siam.

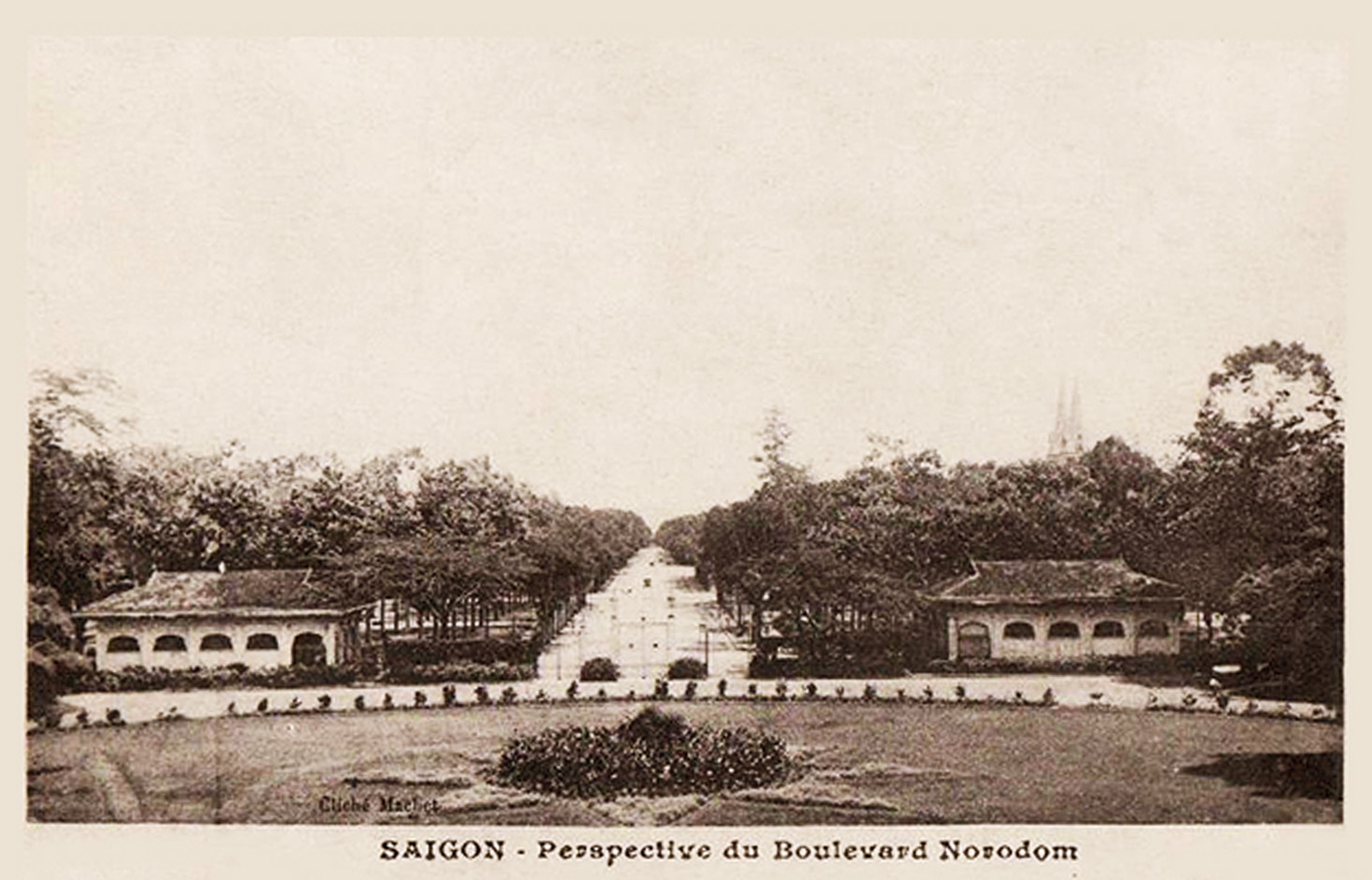

A corner of the Jardin botanique et zoologique de Saïgon

Many of these he sourced personally – during his 12 years in the post, Pierre is said to have spent much of his time combing the region’s forests and savannahs, gathering what became one of the largest and richest tropical plant collections ever amassed by a single individual.

Today, Pierre is probably best remembered for the major contribution he made to the beautification of Saigon’s public spaces. In his large nurseries at the Jardin botanique and in the gardens of the Norodom Palace, he cultivated many of the trees and shrubs which were later transplanted to provide shade along Saigon’s major boulevards and in newly established public squares and parks. Pierre devoted particular attention to the Jardin de la ville, now Tao Đàn Park, where he planted several rare and unusual species, gaining for it the reputation as the “bois de Boulogne of Saigon.”

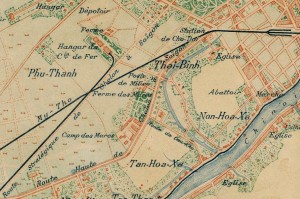

The Ferme expérimentale des Mares pictured on an 1895 map of Saigon

Under Pierre, the Jardin botanique et zoologique also made an important contribution to the development of agriculture in Cochinchina, by supplying colonial settlers with large quantities of fruit trees and industrial crops.

Within just a decade, Pierre transformed the Saigon Botanical and Zoological Gardens into one of the leading institutions of its kind in East Asia. However, by 1875 it had outgrown its facilities and Pierre was therefore instructed to set up an experimental farm on a 120ha site within the compound of the former Pagode des Mares, which then stood near the junction of modern Phạm Viết Chánh and Cống Quỳnh streets in District 1. In subsequent years, this Ferme expérimentale des Mares carried out important research work and succeeded in developing more efficient varieties of coffee, mango, pandanus, jute, indigo and sugar cane.

During his 12 years in Saigon, Pierre also taught botany at the Collège des Stagiaires, where he is said to have acquired the nickname “Pétrus Botanico.”

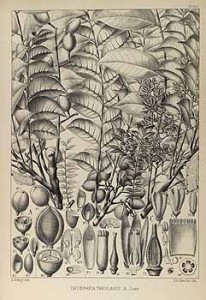

An illustration by E Delpy from volume 4 of Pierre’s Flore forestière de la Cochinchine

Pierre returned to Paris in 1877 to devote more time to his research, and it was during this period that he worked on his magnum opus Flore forestière de la Cochinchine, which was published in multiple volumes from 1881 to 1894. Said to be one of the most important books on tropical forest flora ever written, it was described by Pierre’s contemporaries as “a veritable monument of science and erudition” and a “bible for all botanists who are curious about the secrets of colonial flora.” In his later years, Pierre also wrote many scientific articles for various learned journals, including the Bulletin du Jardin colonial, the Bulletin de la Société Linéenne de Paris and the Bulletin du Muséum de Paris.

Several plant genera were named after Pierre, including the pierreodendron of the sapotaceae family and the pierrea of the flacourtiaceae family.

Jean-Baptiste Louis-Pierre died on 30 October 1905 at Saint-Mandé in the eastern suburbs of Paris, where he was buried. In February 1933, to commemorate his work and academic research, the French Scientific Council installed a marble bust of Pierre in the Jardin botanique et zoologique de Saïgon. This was renovated during the Zoo’s 130th anniversary celebrations of 1994.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.