By the time Emile Gsell took this photograph of the Grand Canal or Canal Rigault de Genouilly in 1882, all except its lower section leading to the city market had been filled

This is an excerpt from a lecture delivered before the Geographical Society of Lille on 3 March 1883 by M A Petiton, a mining engineer from La Grand-Combe in Gard (Languedoc-Roussillon) who was recruited by the administration of Rear Admiral de la Grandière as Chief Engineer of the Cochinchina Mines Service to carry out geological and mining studies throughout Indochina. In the event, by the time of his arrival in October 1868, de la Grandière had died and funding for geological exploration had been cut drastically by the new administration of his successor, Rear Admiral Ohier (5 April 1868-11 December 1869). Rather than being sent back to France, Petiton was forced to remain in Saïgon until 1870 “with only the financial means for insufficient actions,” continuing his geological studies largely at his own expense. His disillusionment with the colonial authorities in Saïgon is evident in much of his writing.

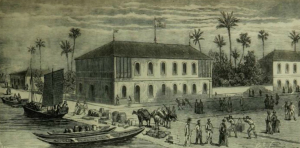

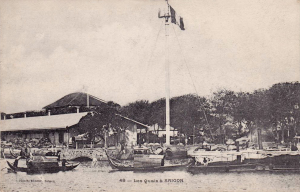

Saigon harbour in the late 1860s

The general appearance of Cochinchina, when you arrive by sea off the coast of Cap St-Jacques [Vũng Tàu], fills one with sadness. This is due to several different features of the country itself; however, I think that this first impression has a lot to do with the very low elevation of the coastline; as he arrives, exhausted after a long journey, the earth seems to flee in front of the passenger’s eyes. With the exception of the small mountains around Cap St-Jacques and the general massif of Baria on the right, you can see only low, marshy land, hardly distinguishable from the sea.

The journey up river to Saïgon hardly does much to reduce this feeling of sadness, with its monotony of river banks covered with mangroves. It seems almost as if there is no land in this country, that its entire surface is swampland!

When arriving in Saïgon, the first question one asks is: where is the city? When I first arrived, I asked seriously which side of the river it was on. I must say, and I was not the only one who had this impression, that at first sight Saïgon seemed a dismal place. Apart from a few large buildings – the Messageries nationales, the famous Maison Wang-taï, and four or five cafés along the waterfront – there was not a lot to see.

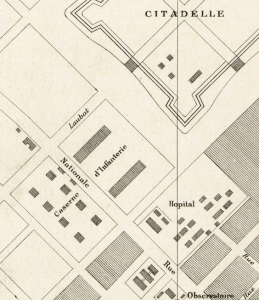

The Projet de ville de 500.000 âmes à Saïgon of 30 April 1862 by Lieutenant Colonel Paul Coffyn

We anchored in front of the Arsenal, that’s to say beyond the city.

I came ashore in light rain, under the cover of a grey sky. I walked past the general stores of the Navy, making my way from the dock to the place du Rond-point [now Mê Linh square].

Saïgon felt to me not like a city, but rather like a sketch of a city.

Indeed, I was not wrong to say this, because some years earlier, a French officer with unlimited confidence in the future of the colony drew up a plan of the layout of the capital of Cochinchina for a future population of 500,000 souls [the Projet de ville de 500.000 âmes à Saïgon of 30 April 1862 by Lieutenant Colonel Paul Coffyn of the Marine Engineering Corps Roads and Bridges Department]. In this plan, Saïgon stretches out for several kilometres over marshy land. The officer drew long lines at an angle of about 45° from the river, along with a series of other perpendicular lines which met the others; thus was the city drawn.

As I walked, I saw a number of caïnhas [the word used by the French for a local house, from the Vietnamese cái nhà] looming out of the mud. The caïnha is a horrible construction built by the Annamites, with a low roof and burning tiles that reflect heat from the sun by focusing it on your heads.

A drawing of the first governor’s palace from the 1931 book Iconographie historique de l’Indochine française (1931)

It was right in the midst of these caïnhas that we built our first Governor’s palace, a temporary wooden building with a large reception room in the shape of a barn. At that time I felt that the building was perfectly adequate for our colony.

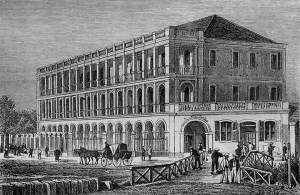

Since then, at enormous expense, we have built the Messageries building, which is separated from Saïgon by the arroyo Chinois [Bến Nghé creek]. A Chinese known throughout Saïgon, named Wang-Taï, also built a large colonnaded house on the quayside between the arroyo Chinois and the Grand arroyo [modern Nguyễn Huệ boulevard]. The location of this “Maison Wang-Taï” [the structure rebuilt in 1887 to a design by Alfred Foulhoux as the Customs House] is regarded as the centre of Saïgon. It has two floors with verandahs and contains the Town Hall, the residence of the Mayor, who is truly the best accommodated official in Saïgon, a post of the Central Police Station and the office of the Secret Police (a new institution created in Saïgon).

Another organisation based here is the Grand cercle, which counts among its members almost all of the officials and naval officers in Saïgon and a small number of marine infantry officers, but very few traders. This is because the traders have their own Cercle du commerce, which is less important than the Grand cercle.

The Maison Wang-Taï

Almost the entire first floor of the Maison Wang-Taï facing the arroyo is occupied by the Grand cercle. In the evening one can see light gleaming from the windows as the regulars play cards or walk along the veranda, smoking; this is about the only thing to do in the city when night falls, and many Europeans may be found here.

Next to the maison Wang-Taï, there is a canal several hundred metres long, which runs perpendicular to the river [the lower end of modern Nguyễn Huệ boulevard].

The construction of new masonry walls alongside this canal cost a great deal of money. It seems that we attach great importance to the completion of this canal for the unloading of cargo brought by different Annamite ships. However, I would be very happy to hear the considerations that led to the execution of this expensive work, as I fear that because of constant silting, the upgraded canal will not serve us as well as we would be entitled to expect.

Another view of the Grand Canal or Canal Rigault de Genouilly

This canal is called the Canal Rigault de Genouilly (after the Navy Minister, Admiral Rigault Genouilly, who was one of our first Cochinchinois); it is bordered on the right by European and some Chinese and Malabar houses, and on the left by Chinese houses, the main city market [1870-1914] and a number of Chinese shops.

The canal once continued further, but it now ends near the church. However, the filling of the upper end of the canal was carried out imperfectly, and it currently forms a swampy rectangular square, lined with houses!

On the left side of this rectangular square is a bowling centre. So that I don’t have to mention it again, I will briefly describe this game of bowling, which is played mainly in the English colonies, usually in the evenings.

The bowling centre is a large rectangular hangar, about 4 metres in width, which contains two parallel polished bowling alleys, separated by a channel. The servant boys place skittles at the far end of each alley and the players stand at the other end, using just one hand to roll a huge ball along the alley with the aim of knocking down the skittles. The balls roll quickly and can cause havoc with the skittles.

The second central market (1870-1914) on the Grand Canal

However, if the player is unlucky, or has no skill, the ball will simply roll down a slope into the central channel. The servant boys return the balls to the players and also keep their scores using a kind of large polygonal glass lantern with numbers, illuminated by coconut oil. This scene takes place amidst the noise of rolling balls, scattered skittles and the general hilarity of the young German and English regulars, who greatly enjoy this entertainment.

What shall I say of the church? Nothing. This building [the Église Sainte-Marie-Immaculée, inaugurated on 8 June 1865 on the site of the modern Sun Wah Tower at 115 Nguyễn Huệ] is just a temporary church; part of the central nave closest to the chancel is reserved for Europeans and is equipped with chairs. The rest of the building has wooden benches. The church bell is mounted on a frame. Outside the building, not far from the church, is the presbytery, which I believe is the special property of the priest.

At the moment they are building a new cathedral near the government palace, along with a palace for the Bishop, an old cleric who has already lived in Indochina for nearly 30 years.

The inauguration of the Église Sainte-Marie-Immaculée on 8 June 1865

We can only hope that he will still be alive to profit from this good administrative intent, because, as he himself has said, he does not have the time to wait.

Leaving the filled upper section of the canal and walking up towards the Governor’s Palace, we pass two or three large European houses, the office of the Directorate of the Interior and the residence of its Director, the Treasury, the Post Office, the General’s residence, and finally the Governor’s Palace itself.

Nearby are the Marine Infantry Barracks, located in the former Camp des lettrés [the Trường thi or royal mandarinate examination yard, which once stood outside the citadel], the Military Hospital and the Artillery Barracks. I have little to say about these places, other than that conditions for patients in the hospital are as bad as those for the soldiers in the barracks. It is deplorable that the first money we have to spend is not used to improve this state of affairs. We should not have to tell the public that our colony has three main institutions in continuous operation: a barracks, a hospital and a cemetery.

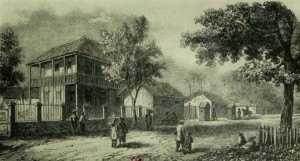

An 1866 photograph of the original building of the Sainte-Enfance (Holy Childhood), run by the Sisters of the Order of St-Paul de Chartres

Continuing my journey along rue Isabelle [modern Lê Thánh Tôn street] as far as the Botanical Gardens, I come to the building of the Sainte-Enfance (Holy Childhood), run by the Sisters of the Order of St-Paul de Chartres, which takes care of the education of a number of little orphans. The Chapel of the Sainte-Enfance is surmounted by a remarkable steeple, the spire of which can be seen from the Saïgon River, long before you arrive in Saïgon.

We must not forget to point out that there is also a convent of five Carmelite nuns, right next to the Sainte-Enfance.

Further down towards the arroyo are the Arsenal buildings, which are currently under construction.

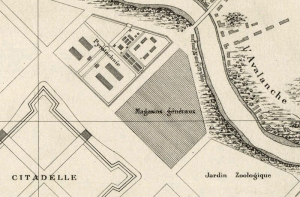

Above the Sainte-Enfance is the Seminary, and a little further, near the Botanical Gardens, a Christian Brothers school known as the College d’Adran. Finally, we arrive at the Botanical Gardens, located between the Arsenal and general stores of the Navy, close to which is the gunpowder magazine.

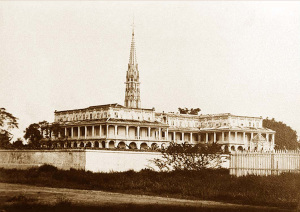

Road construction outside the new Governor’s Palace in the early 1870s

At the opposite end of town, beside the route de Cholon, are the home of the Attorney General, the Prison and the Central Police Station. The latter is a true monument which cost a great deal of money.

Just a stone’s throw from the Central Police Station, on the same plateau, we get a glimpse of the new Governor’s Palace [built from 1868-1873 and later known as the Norodom Palace], under construction in the middle of a very beautiful park; the structural work of this palace has already been completed. This location is one of the least unhealthy places in Saïgon, being a high plateau about 8 metres above sea level.

Saïgon has two Islamic temples and one Hindu temple. These temples are not very remarkable, but in any case, the Indians do not let us visit them. I think, however, that the argument of the piastre would be taken into high consideration, and would probably permit Christians to tread the sacred ground.

A scene alongside the arroyo Chinois

To complete this brief review, I will say that there are still some European houses of just one storey; all the rest of the city is composed of miserable caïnhas, which may have killed more people than all of the other numerous natural causes of ill health in this country.

The streets of Saïgon are wide and the ground is muddy or dusty: for tarmac, we substituted a red clay-iron-silicon based material which was certainly a most unhappy choice. In 1869, the authorities introduced watering trucks pulled by buffaloes to reduce dust; trees planted in the streets for the shade are also watered regularly.

In 1869, there was some momentum to build new houses; at least 40 new homes were built in that year, although it’s true to say that many of those houses only replaced crumbling caïnhas. However, this construction fever did not bring any reduction in rents, which are excessive given the poor conditions of comfort of many of the city’s apartment buildings. Small rooms lacking in breadth and height are rented out for upwards of 6 piastres per month. It seems that we build here without worrying about comfort or hygiene, with the aim of making the most money possible, instead of constructing the large and airy residences which are one of the first needs of the country.

The first European merchant trader’s office in Saigon

Singapore has much better hygienic conditions than Saïgon. I only spent a day or two there, but everywhere I saw houses with ceiling heights of at least 4 or 5 metres, and huge stairways leading to spacious first floor offices. It is true that such buildings must also be rented out at a high price, but they are safe and designed to facilitate the through flow of fresh air. In Saïgon, the government conceded a great deal of land almost free – just 0.75 francs per square metre – to encourage the agents to build. However, out of 20 concessionnaires, I think that just two have built, while the others have mostly engaged in speculation. That is a game they love here in Saïgon.

The location of the first Marine Infantry Barracks either side of the rue National (modern Hai Bà Trưng street) is shown clearly on this 1864 map

I spoke very briefly of the Marine Infantry Barracks; this is a depot of 1,000 to 1,500 men who radiate out from this centre to occupy various posts in the colony. However, I have nothing to add to what I said about the barracks, which are completely insufficient in terms of welfare; moreover, they will be demolished soon. If I am correctly informed, the troops will be installed in new buildings which are being constructed in the old Fort du Nord [in 1870-1873, a larger Marine Infantry Barracks was built over the front section of the ruined 1837 Citadel]. The current barracks are located on either side of the road leading to the village of Gò Vấp [modern Hai Bà Trưng street]. A few hundred metres further north along this road is the cemetery, a vast enclosure surrounded by a bamboo hedge. When you live Saïgon, you quickly learn the way to the cemetery.

There also exists in Saïgon a modest but very useful institution: the Municipal Interpreters’ School, the name of which sufficiently indicates its goal.

One other institution which can be considered as a “building” of Saïgon is the stationary vessel Duperré, which houses all those sailors who do not have any specific purpose. The Duperré is a large floating barracks, a most fantastic ship, the history of which is difficult to understand for those who are not initiated into its mysteries.

In front of the Arsenal is the floating dock, a vast sheet metal structure of incontestable utility; however, you cannot but question the exorbitant price it cost to build, as they say back in France. The Arsenal, which is still under construction, is perhaps the most important establishment from the point of view of material. Its director is an assistant engineer first-class who specialises in shipbuilding; he currently has a large staff of many thousands of men. Every night, you can see a procession of Annamites coming out of the gates of the Arsenal and heading in the direction of Gò Vấp. Since the current Arsenal buildings are temporary, it is unnecessary for me to give a description which will be inaccurate tomorrow.

The main gate of the Marine Arsenal in 1895

The Navy attaches great importance to the Arsenal of Saïgon, in fact I heard more than one person say that we only keep the colony of Cochinchina in order to provide an Arsenal for our national Navy, a place of repairs for the ships of the state. When it is completed, the Arsenal will include various docks and canals, the establishment of which will cost a great deal of money.

I have one sober criticism to make about the way in which we build our institutions in climatic conditions as difficult as those of Cochinchina. I noticed that all of the wood required in the Arsenal has to be brought from a depot on the other side of the arroyo de l’Avalanche [Thị Nghè creek], and that this takes very considerable manpower. Wouldn’t it have been preferable to build a depot on this side of the arroyo, near the Botanical Gardens?

The general stores of the Navy, whose biggest customer is the Arsenal, are, if I am not mistaken, also separated from it by the Botanical Gardens. Is not this a mistake?

And as I have said, these stores are dangerously close to the gunpowder magazine, Is this not another error?

The location of the Botanical Gardens, the general stores of the Navy and the gunpowder magazine are indicated on this 1864 map

I think that the Botanical Gardens would be perfectly able to give up some of its land to make way for a new general stores. If one took away part of their land to build a wood depot, they could easily be compensated with other land a few hundred metres away, further along the arroyo.

The Arsenal employs both Chinese and Annamite workers; the Annamites are pretty good blacksmiths; Annamite boys are strong sail makers, while the Chinese are good modellers for the foundry. In the Arsenal there are less than 20 French employees. I am able to appreciate the efforts of the Director in such conditions and I applaud the difficulties he has managed to overcome.

The governor’s yacht, the Ondine, is currently moored at a fixed station nearby, in the port of Saïgon.

Many steam ships work in and around the naval port in the service of the port authority; sampan owners unfortunate enough to find themselves in the path of these vessels would be sunk quickly. This is a serious problem in the Saïgon River.

A late 19th century view of the Signal Mast

Several steam gunboats for the arroyos and two or three other vessels of a slightly larger tonnage for the sea complete the naval port.

Two courier ships are usually anchored in the harbour – one in front of the Arsenal and the other a little further down the quayside, awaiting the return of the third. The latter is making a return journey to and from Marseille which usually takes around three months, including a three-week stopover in Suez.

In front of the Maison Wang-Taï is the commercial port. There are some 30 ships in the harbour, including French, German and English vessels.

The Director of the Commercial Port has his residence and offices between the Maison Wang-Taï and the arroyo Chinois. In front of this house is a very interesting Signal Mast, which heralds the arrival of the mailboat from France, by means of a complicated system of flag signals. At the foot of the Signal Mast is a pier with a stairway, around which is grouped a swarm of sampans. For a nominal fee, the boatmen will take you to a ship, or to the buildings of the Messageries nationales located on the other side of the arroyo Chinois. Like their colleagues in other countries, they are all cheeky, loud and arrogant.

This map from 1863 shows the Fort du Sud, located next to the river in what is now District 4.

The limit of the harbour of Saïgon downstream is the Fort du Sud. This fort is located about two kilometres from the Maison Wang-Taï, on the right bank of the Saïgon River. It was and still is a place of punishment for badly behaved soldiers and sailors; however, nowadays we use it very little. It is this fort which protects the maritime entrance to the Saïgon harbour.

I did not mention, I think, the administration of justice in Saïgon.

In Saïgon there is a legal service, led by an Attorney General; a Court of Appeal consisting of two Counsellors, a President and a Hearings Officer; and a Court of First Instance composed of a President (Judge) and an Investigating Judge. There is also an Indigenous Justice Appeals Tribunal, run by Inspectors of Indigenous Affairs.

All of these people work at the Palais de Justice, a caïnha as miserable as the rest. Moreover, there is something particularly curious about the judicial staff, which is that rarely does the holder of a particular office fulfil the functions of that office. So in practice, we see the following in Saïgon, where judicial staff are cheap:

Legal personnel pictured in 1875.

The President of the Court is Attorney General; a Counsellor is President, the Hearings Officer is Prosecutor; the Prosecutor is Hearings Officer; and a humble secretary in the Directorate is the Advocate General to the Court. For all we know, he could soon be President of the Court – no-one in Saïgon would be surprised.

I laugh a little, but it saddens me deeply to see French law being applied to a country and people for which it was not designed. Sometimes this results in monstrous absurdities which can lead dedicated people who are keenly interested in Cochinchina’s different races to despair.

As to the Indigenous Justice Appeals Tribunal, I am anxious to see it work properly, because a lot of bad judgments must be reviewed. Suffice it to say that the Inspectors of Indigenous Affairs who are responsible for administering justice in this area are mostly inexperienced young officers.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.