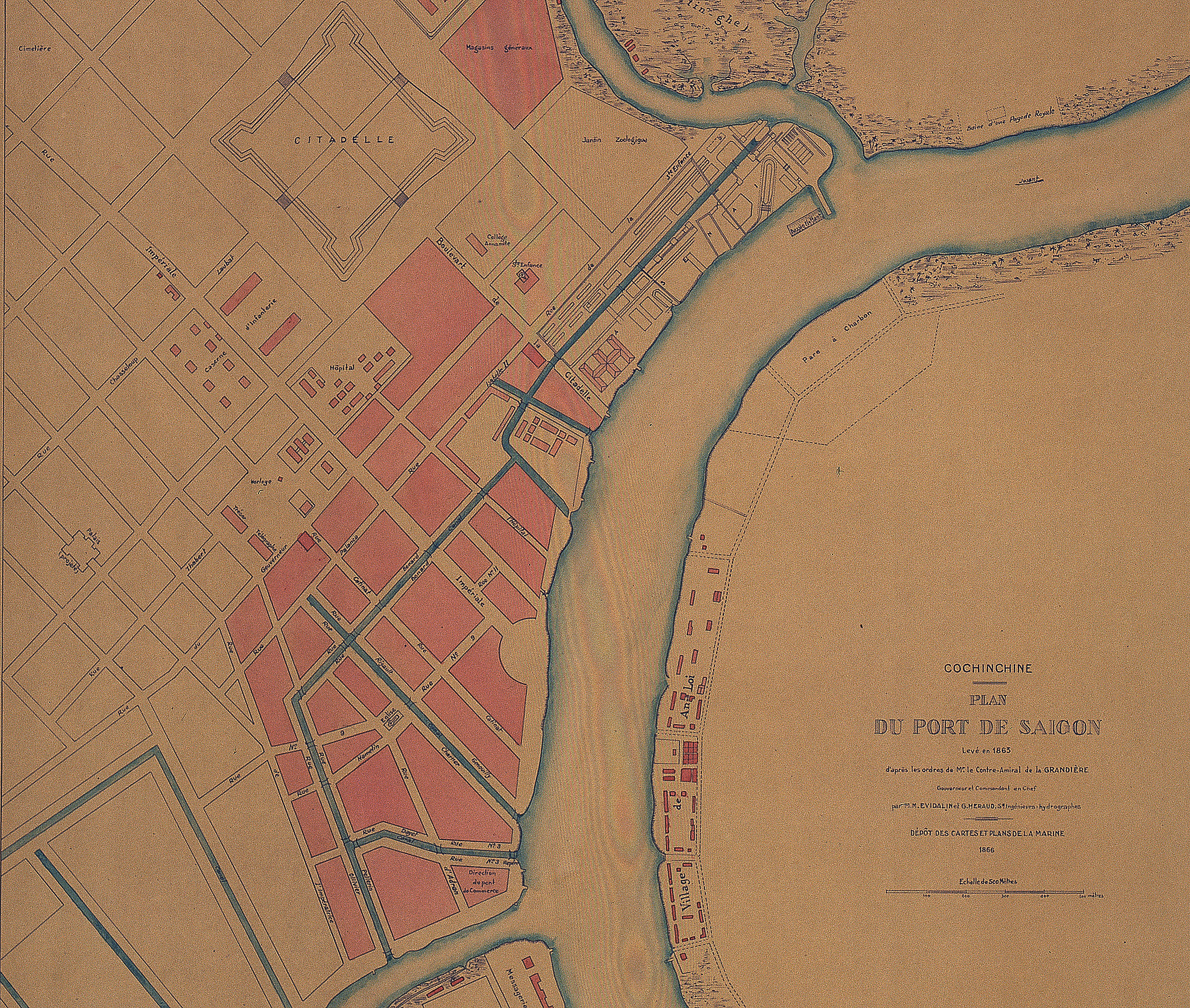

This 1865 map shows the Saigon inner-city canal network at its height (courtesy of Institut Parisien de Recherche Architecture Urbanistique et Société, IPRAUS)

This article was published previously in Saigoneer http://saigoneer.com

When the French arrived in 1859, both Saigon and Chợ Lớn were criss-crossed by networks of canals and creeks, making it possible for boatmen to travel right through both city centres without stepping ashore. However, while most of Saigon’s waterways were filled as early as 1868 to make way for spacious tree-lined boulevards, those of Chợ Lớn survived until as late as 1925. This two-part feature looks at the history of the ancient waterways in both cities – starting with Saigon.

A 1795 map of Saigon showing the original two canals (courtesy of IPRAUS)

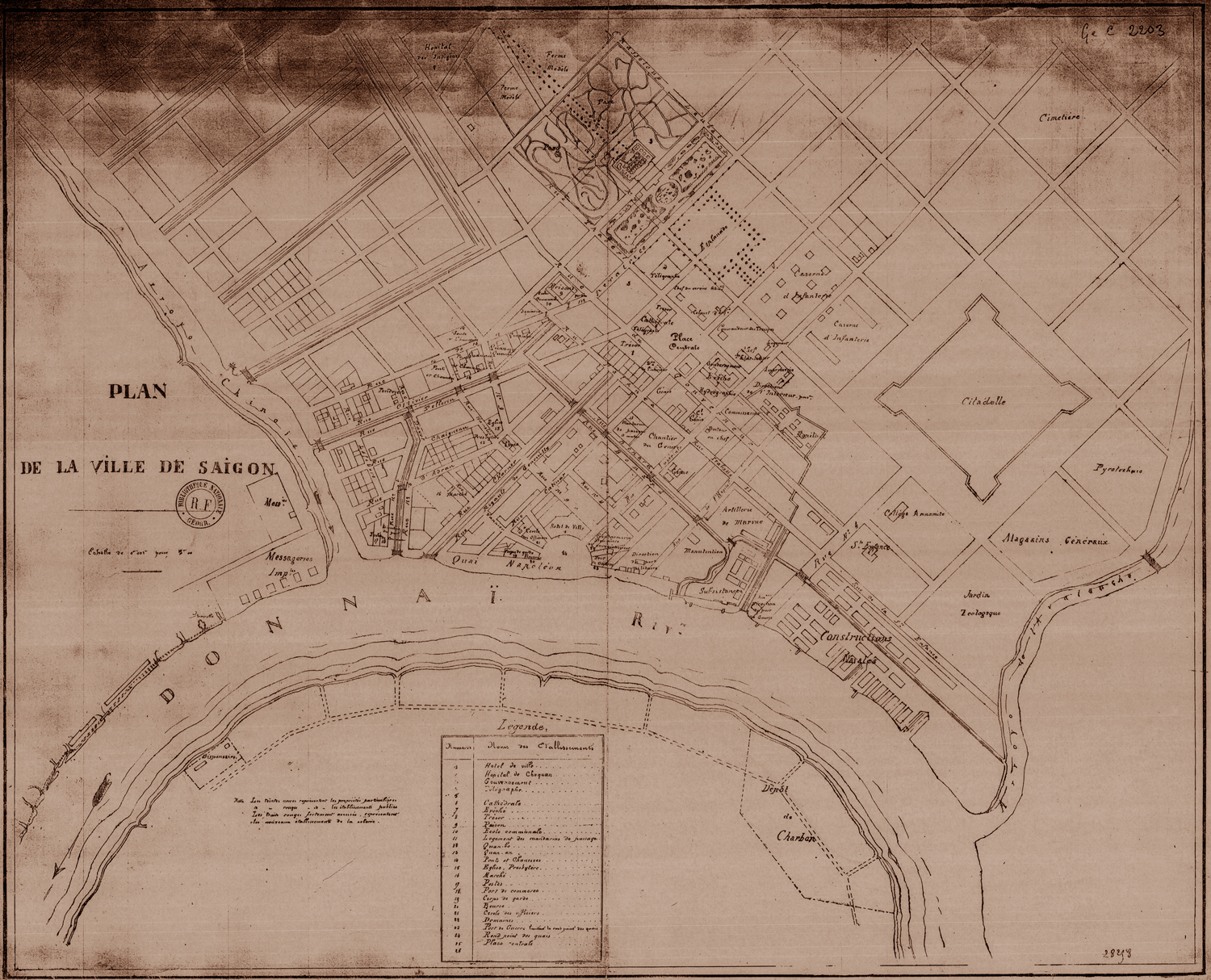

Enclosed by the Saigon river to the east, the Thị Nghè creek to the north, and the Bến Nghé creek to the south, Saigon’s main urban area, known as Bến Nghé, acquired its own small network of inner waterways from an early date.

The origins of this inner waterway network may be traced back to the construction of the 1790 Gia Định Citadel, when a canal, later known to the French as the “Grand Canal,” was dug northwestward along the path of modern Nguyễn Huệ boulevard, to provide water access to Citadel’s main Càn Nguyên (south) gate.

Several maps of the 1790s also show the existence of another canal or creek named the rạch Cây Cám, which ran northwestward from the Saigon river, midway between the mouths of the Bến Nghé and Thị Nghe creeks, as far as modern Lê Thánh Tôn street.

In subsequent years, a third canal was dug westward along the path of modern Hàm Nghi boulevard, providing waterborne access to the old city market, which stood in the vicinity of the modern Hàm Nghi-Tôn Thất Đàm street junction until 1869. Writing in the 1880s, scholar Pétrus Ký tells us that this was known as the rạch Cầu Sấu (“Crocodile Bridge Canal”), because “it was used for breeding crocodiles that were sold for butcher’s meat.”

Merchant shipping on the arroyo Chinois during the colonial period

Saigon’s inner-city waterway network was completed with the construction of a cross-town canal, which ran northwestward from the Bến Nghé creek along what is now the lower end of Pasteur street, before turning to link with the rạch Cây Cám. On its way, this cross-town canal connected with both the Crocodile Bridge and Grand Canals.

In this way, by the time the French arrived in 1859, merchants were already able to circumnavigate the entire city by boat.

In around 1862, Lieutenant Colonel Paul Coffyn of the Marine Engineering Corps Roads and Bridges Department oversaw the dredging and widening of the cross-town canal, in order to improve access for merchant ships. As a result, the canal briefly became known to the French as the Canal de jonction (Junction canal), or less formally, the “Canal Coffyn.”

However, by that year there was already growing debate amongst colonial settlers about the extent to which the notoriously smelly canals and creeks – used by many for the dumping of waste – were contributing to the rapid spread of serious endemic diseases such as cholera, malaria, intestinal parasites and dysentery. Despite opposition from the traders who used the waterways for freight, the hygiene lobby eventually won the day. From 1863 onwards, Saigon’s city-centre waterways were systematically filled.

Another colonial era photograph of merchant shipping on one of the arroyos

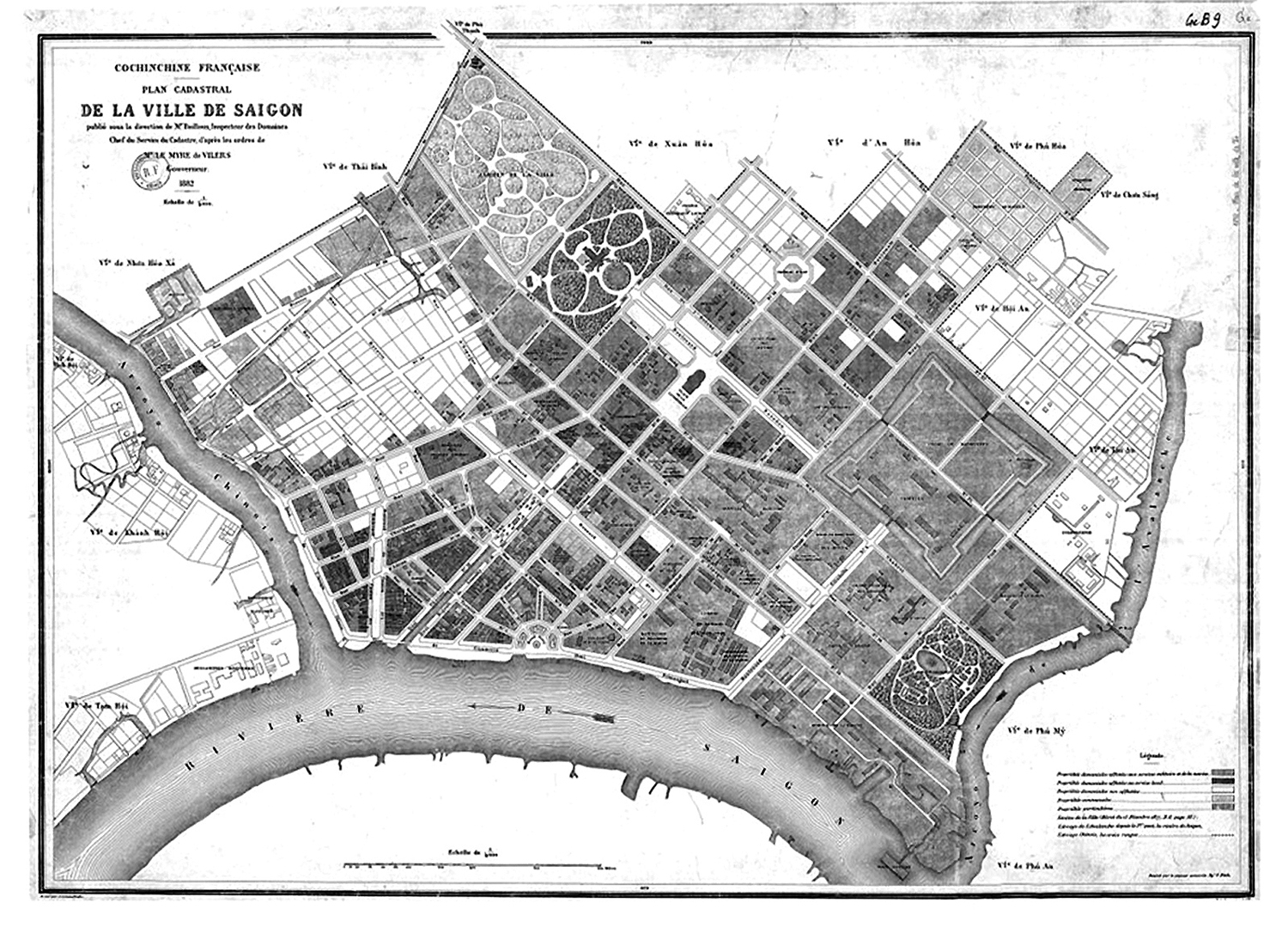

First to go were the recently-upgraded “Canal Coffyn” and the upper section of the “Grand Canal,” which were filled to create boulevards Bonard (modern Lê Lợi) and Charner (modern Nguyễn Huệ) respectively. By 1868, the “Crocodile Bridge Canal” had become boulevard de Canton and the waterway along what is now lower Pasteur street had also been filled to create rue Pellerin.

The lower end of the “Grand Canal” survived for a further two decades. After 1870, when the city market was relocated to a new site right next to it (the block currently occupied by the Treasury building and Bitexco Tower), this sole-surviving inner-city waterway become known locally as the Kinh Chợ Vải or “Fabric Market Canal,” because the market was famous throughout the city for its fine fabrics.

By 1890, the Kinh Chợ Vải had also been filled, facilitating the extension of boulevard Charner as far as the riverfront. However, it seems that it was not quickly forgotten by local people, who for many years afterwards continued to refer to boulevard Charner as đường Kinh Lấp or “Filled canal street.”

The early filling of Saigon’s city-centre canals and creeks – attributable mainly to the presence of a large and vocal resident French community in the colonial capital – contrasted strongly with the situation in Chợ Lớn, where the powerful Chinese associations were able to protect their inner-city waterways for nearly 60 years after the French conquest.

To read part 2 of this two-part feature looking at the lost inner-city waterways of Chọ Lớn, click here

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.

This undated map also shows the Saigon inner-city canals before before any of them were filled (courtesy of IPRAUS)

By 1882, all that remained of Saigon’s inner-city canal network was the lower end of the “Grand Canal” (modern Nguyễn Huệ boulevard)

An 1880 photograph by Emile Gsell of the lower end of the “Grand Canal” (modern Nguyễn Huệ boulevard)

Another 1880 photograph by Emile Gsell of the lower end of the “Grand Canal” (modern Nguyễn Huệ boulevard)