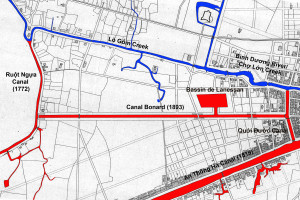

This late 19th century map, based on Trần Văn Học’s map of 1815 with added details from various 19th century sources, shows the old Tai Ngon Market and also illustrates how the 1819 An Thông Hà Canal by-passed the city.

This article was published previously in Saigoneer http://saigoneer.com

When the French arrived in 1859, both Saigon and Chợ Lớn were criss-crossed by networks of canals and creeks, making it possible for boatmen to travel right through both city centres without stepping ashore. However, while most of Saigon’s waterways were filled as early as 1868 to make way for spacious tree-lined boulevards, those of Chợ Lớn survived until as late as 1925. In this second instalment of a two-part feature, we look at the history of the ancient waterways in Chợ Lớn.

To read part 1 of this two-part feature looking at the lost inner-city waterways of Saigon, click here

Originally founded in the 1680s by refugee supporters of the overthrown Ming dynasty, the earliest incarnation of Chợ Lớn, known as the Xã Minh Hương, was established as an outpost of a larger Ming refugee settlement in Biên Hòa. Initially, it comprised a small cluster of houses on the north bank of the Bình Dương river, which at that time ran along the path of what is now Hải Thượng Lãn Ông street.

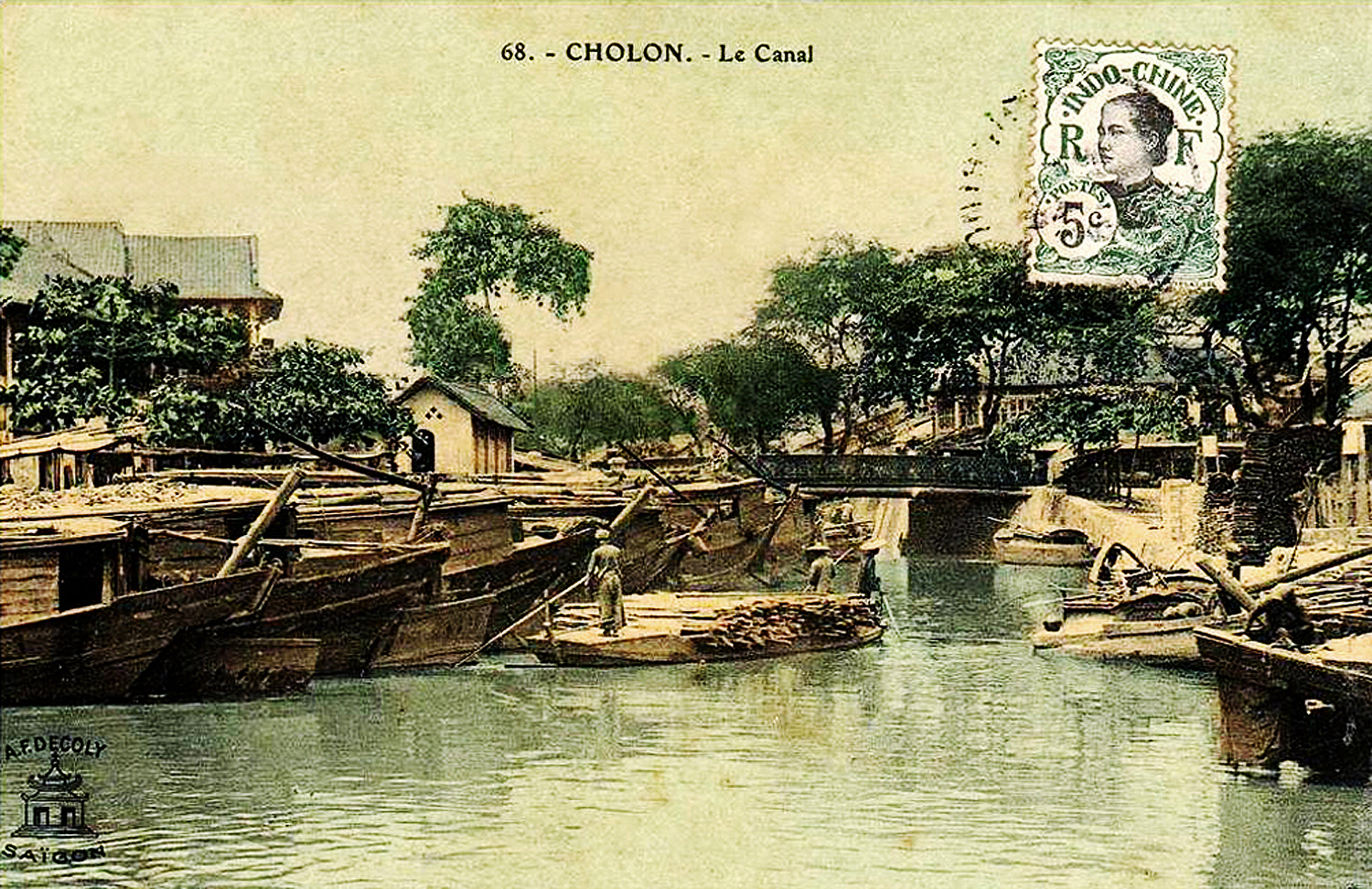

Chinese merchant shipping in Chợ Lớn

Unable to return to China, its Minh Hương founders intermarried and gradually evolved into a resident mixed-race community with its own unique ethno-cultural identity, while later settlers from Qing-dynasty Fujian and Guangdong provinces tended to marry within their ethnic group.

During the 18th century, the partnership between the Minh Hương (who controlled the domestic shipping and processing of rice and other agricultural products from the Mekong Delta) and the later Qing Chinese settlers (who shipped these products overseas) turned the town into an important economic hub – as well as an increasingly important source of revenue for the Nguyễn lords. Constructed in 1772 by the Nguyễn government to by-pass several badly-silted creeks, the Ruột Ngựa or “Horse Guts” Canal (so named because of its shape) was designed to facilitate the activities of the merchants and thereby guarantee a high level of trade tax revenue.

During the subsequent Tây Sơn War (1770-1802), most of the Minh Hương and Qing Chinese merchants in this area remained loyal to the Nguyễn lords, but this left them vulnerable to attack by the rebels. Following a Tây Sơn offensive against the Minh Hương settlement of Biên Hòa in 1778, many of its citizens fled to the Xã Minh Hương, increasing the latter’s population significantly. Soon afterwards, a new market was established in the north of the town, on the site of the current Chợ Rẫy Hospital. A canal known as the Phố Xếp Canal was then dug along the path of modern Châu Văn Liêm street, so that merchants could access the market by boat from the Bình Dương River.

On this 1893 map of central Chợ Lớn, the original Bình Dương River and related creeks are shown in blue and canals shown in red.

However, in 1782, the Tây Sơn launched a devastating attack on the Xã Minh Hương itself, causing widespread damage and killing many of its citizens. Soon afterwards, the Xã Minh Hương was rebuilt with new wharfs and embankments to guard against flooding and invasion. As a consequence of this, the market and the town gradually became known by the new name 堤岸 – Dī Àn in Mandarin – meaning “embankment.” Many historians believe that this name, spoken in the Cantonese dialect, evolved into the local form “Tai Ngon,” which was then written on several 19th century maps as “Saigon.” In 1859, the French appropriated this name and used it to describe their new administrative capital, the former Bến Nghé. Deprived of its original name, the former Tai Ngon became known simply as Chợ Lớn or “Big Market.”

During the reign of King Gia Long (1802-1820), Chinese commercial knowledge and labour was highly valued. However, by this time both the Ruột Ngựa canal, and the Lò Gốm creek which connected it to the Bình Dương River, had also become badly silted, causing transportation difficulties for those merchants travelling back and forwards to the Mekong Delta. In 1819, King Gia Long’s Vice Regal government responded by digging a large new canal known as the An Thông Hà, which by-passed Tai Ngon town centre completely, downgrading the westernmost section of the Bình Dương River, the Lò Gốm Creek and the Ruột Ngựa canal into a waterway for local shipping. Today the An Thông Hà Canal forms part of the main Tàu Hủ Creek.

On this 1893 map of western Chợ Lớn, the original Bình Dương River and related creeks are shown in blue and canals shown in red

As mentioned in the first part of this feature, the French arrival in Saigon in 1859 was followed soon afterwards by the filling of all of the city-centre canals and creeks for reasons of hygiene. In contrast, Chợ Lớn had no large and vocal French population, and its powerful Minh Hương and other Chinese congregations relied heavily upon its creeks and canals for commerce. Consequently, they were able to lobby successfully for the retention of their inner-city waterways until as late as 1926 – over 60 years after the French conquest.

In fact, in 1889, the year in which the filling of the last section of the Grand Canal got under way in Saigon, work had just began in Chợ Lớn to dig a brand new waterway – the Canal Bonard – with the aim of improving access by merchant boatmen into the west of the town.

Following the relocation of the main city market to the site of the current Chợ Lớn Post Office in the 1860s, the old Tai Ngon Market was abandoned and the Phố Xếp Canal lost its purpose. Starting in the 1890s, it was progressively filled.

The end finally came for Chợ Lớn’s inner-city waterways in 1923-1926, when, under the influence of Hà Nội-based urbanist Ernest Hébrard, the Cochinchina authorities finally got to work filling Chợ Lớn’s creeks and canals with the aim of improving traffic circulation within the town.

Today what remains of the Canal Bonard is little more than an open sewer, surrounded by temporary housing

However, the Canal Bonard was pointedly excluded from this scheme, possibly at the instigation of wealthy businessman and philanthropist Quách Đàm, who had undertaken to fund the construction of a larger city market to replace the small and now landlocked Marche Centrale de Cholon. In 1926-1928, the Bình Tây Market was built right next to the Canal Bonard, Chợ Lớn’s sole-surviving inner-city waterway, thereby ensuring that the next generation of Chợ Lớn’s merchants would enjoy direct access by boat to the city’s main market.

The Canal Bonard was abandoned in the 1970s, and in 2000 most of its eastern section was filled. Today, the surviving section of this historic inner-city waterway is today little more than a rat-infested open sewer, surrounded by temporary housing.

However, in 2015, work began on a US$100 million project to reinstate this historic canal in its entirety, with the aims of reducing environmental pollution, improving public health and reducing chronic flooding. Temporary housing will be relocated and the quaysides – which still contain a number of important heritage buildings – will be landscaped for both visitors and residents to enjoy. For more details see Icons of Old Saigon: The Canal Bonard.

The bridge over the entrance to the Chợ Lớn Creek, pictured in the late 19th century

The junction between the Chợ Lớn Creek and the Phố Xếp Canal, pictured in the late 19th century

An aerial view of the Canal Bonard in the 1940s

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.