In mid 1888, wealthy French widow Louise Bourbonnaud set off alone on an extended voyage of discovery which took in India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Singapore, Cochinchina, China and Japan. She spent over a week in Saigon and her 1892 book Les Indes et l’Extrême Orient, impressions de voyage d’une parisienne provides us with a fascinating, if somewhat condescending, account of late 19th century colonial life. This is the fourth of a series of instalments from her book, translated into English.

To read part 1 of this serialisation click here.

To read part 2 of this serialisation click here

To read part 3 of this serialisation click here

Wednesday 29 August 1888

Louise Bourbonnaud

Yesterday evening, on returning home, I found a letter from the police station lying on my table. I was a little surprised at first, and while wondering what I may have to reproach myself about, I opened the letter and read:

Madame,

I have the honour to be responsible for civilian population record keeping. Kindly complete the enclosed information sheet.

For the Commissioner:

Brigadier-Secretary,

Signed: X…

I fill in the sheet: Full name, date and place of birth, address, etc. I haven’t forgotten my skills as a member of the Geographical Society, the Society for Aid to the War Wounded, the Royal Academy of Ireland, etc, etc!

This morning, I send back the sheet with my felicitations to the Commissioner. This duty done, I barely have time for lunch before going outside to call a Malabar. A driver passes and I signal him to stop. As I’m getting in, he says:

“Ah! It’s you, the lady for whom the journeys are never long enough! I’m sorry, but I can’t take you. My comrades have warned me about you. No, no! I can’t!

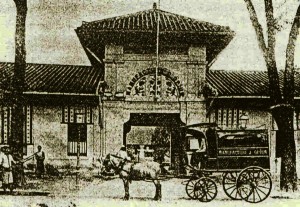

The Manufacture d’Opium de Saïgon at 74 rue Paul Blanchy (Hai Bà Trưng street)

We finally agree, however, and for a piastre, I’ll be taken around for two hours; but it is with great difficulty that I get this result!

Passing the dock and then heading north through Saigon, I read the sign on a large facility: “Manufacture d’opium.” This is where they process the drug which the poor Chinese consume so much of, and which is so important to the colonial budget.

Passing through an Annamite village a little further on, I see an old woman on her doorstep selling a coffin. No doubt waiting until the next person in the village dies. One should not be surprised to see that here, because the coffin is furniture that is sold everywhere, both by individuals and larger companies.

We pass some more buffalo; they are huge, they look like elephants and even share their colour. While they don’t have the tusks of the pachyderm, they have horns and these can be at least as dangerous.

There are rice fields on this side of the city: to be good rice, it must be immersed completely in water; rice raised on dry land is worthless.

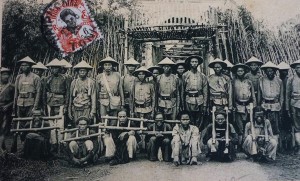

Prisoners and militia, Cochinchine

We pass a team of prisoners working on the road; they are at least 60 of them, led by some guards armed with cudgels which are used to chastise the lazier ones or those who try to escape.

These prisoners wear short pants, they have a small jacket and on their heads a small Japanese-style hat. They must work even during siesta time, and this must be especially hard for them. The government of the colony takes advantage of its prison labour, and that is only fair, because everything this world is so expensive.

Returning from my excursion, I pass the offices of the Messageries maritimes, but they are closed: its employees worked on Sunday to service the arrival of the ship, so they were given leave today.

When you want to talk to local people, it pays not to speak in long sentences or to use figures of speech, as they would certainly not understand. You have to go straight to the point, using the least words possible: “I not want… I not go there… it bad… it good.” If what you say is too complicated, there is a risk that the listener will answer yes or no without understanding the question that has been asked.

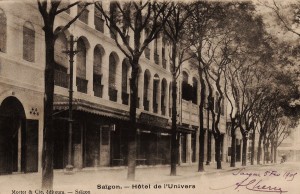

Louise Bourbonnaud stayed at the Hôtel de l’Univers

Tonight I will have dinner at the home of Mr de Blainville, so I return to the hotel to get ready. In the hall, I stop for a moment to read the latest bulletin from the news agency Havas, which is displayed on a special table. This is a nice idea, those who want to keep abreast of events can do without buying newspapers, which, as I have already said, are quite expensive here.

On my arrival at the residence of my gracious hosts, the eldest son of Mr de Blainville scarcely gives me time to take off my hat before leading me into the garden to show me his horses and carriages, and the beautiful flowerbeds around the house. Here may be found all the beautiful plants which in our northern climes can only live in greenhouses; they are full of vigour, tapping into the fertile soil and thriving here as they would never do back home.

Going back to the first floor, I find the whole family assembled under the verandah – here we pronounce it verande – that is to say the large colonnaded balcony that surrounds the house. Ah! What excellent conversation we make in the cool of the evening, gently lounging in wicker chairs, with no other occupation than to wave our fans! Tonight we talk about the army, and during the conversation, I recount my first impressions of meeting the Annamese riflemen.

A senior colonial administrator’s residence in Saigon

When I get back to Paris, I say, I will not fail to speak of these brave little soldiers, who have good French officers and NCOs to lead them into battle, if necessary. Cochinchina is a beautiful colony, which not only stands on its own, but also generates 20 million Francs each year for France, not to mention the millions it pays to Tonkin. Few people know about this in France, where some newspapers are trying to convince their readers that the colonies are a burden to us. But here I am positioned better than anyone to know the truth.

At 5pm we hear a loud drum roll: this is the signal for the close of the offices. At the same time, a storm occurs and the rain begins to fall with fury, crackling the leaves on the trees that here, on the verandah, we can touch with our hands.

One of the young men brings me a gorgeous rose that I pin on my blouse, and I resolve to keep as a souvenir. Then Mr de Blainville offers me his arm and conducts me into the dining room, where the table is set with the very best china, crystal and silverware, with a basket of flowers in the middle. Nothing is missing. It’s like a wedding feast!

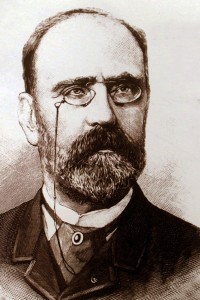

Étienne Richaud, who, after being appointed Résident général in Annam and Tonkin, succeeded Ernest Constans in April 1888 to become the second Governor General of Indochina

Dinner is served by 12 waiters, while half a dozen more stand behind the guests serving the drinks. On the table is the menu, which I assure you, leaves nothing to be desired; the meal is exquisite and I find the asparagus particularly delicious; I see that our French vegetables can grow well here, if they are properly cared for. As a dessert they served a bombe, a nice touch by my hosts who know that on board the Ava, I discovered my weakness for ice cream.

During dessert, the Résident Général, Mr Richaud, enters the room. Everyone rises and Mr de Blainville does me the honour of introducing me to his boss, whose reception is very courteous. As a tourist I’m a little excited, I confess, to be visiting friends in the presence of the highest authority of the colony, the representative of my dear France, this famous “captain-six gallons” who I saw receive the homage of the entire population! But Mr Richaud is a man of extreme affability and simplicity and the high functionary in him quickly disappears to make way for the man of the world. He wants to talk to Mr de Blainville and leaves with him for a trip in a carriage.

Meanwhile, the ladies go to the salon to talk. A cat is lying on the sofa where I go to sit. Its appearance is very funny: its ears are those of a dog and it has no tail! It seems that this is a special breed of cats found in Cochinchina. The animal is not wild and willingly allows us to stroke it.

A carriage waits outside a colonial administrator’s residence

One of Mr de Blainville’s daughters has an excellent knowledge of star charts and astrology. She offers to draw up our horoscopes; although we all profess to scepticism, don’t we feel the least bit curious about what the future holds for us? On one hand, we’re convinced that the fortune teller is a charlatan, but on the other, we still shudder when we are told in a serious voice the fate which awaits us!

Each of us has a go. When my turn comes, she predicts happiness and money. “Money, maybe,” I reply, excited despite myself, “but happiness, no! It is past, my happiness!”

The conversation takes another turn, and when the gentlemen join us, gaiety abounds.

When Mr de Blainville learns that his daughter told us our horoscopes, he also wants his own fortune told, and laughingly exclaims: “It is unfortunate that I am not a widower, otherwise maybe I would marry Madame Bourbonnaud.” And everyone laughs at this joke.

Poor man! He would die, just six months later!

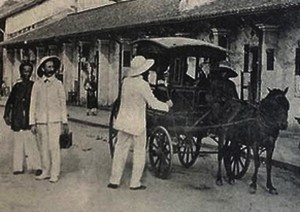

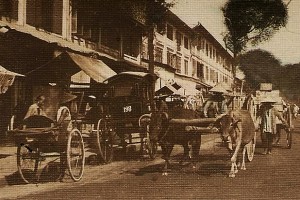

Calling a Malabar on the street

But the hour of parting has arrived and I’m about to take my leave. I am asked to wait a bit and I learn that Résident Général has ordered a carriage with two horses to take me back to the Hôtel de l’Univers. And he will accompany me!

Surprised at such an honour, I protest that I don’t want to cause a disturbance and can easily find a hire carriage to take me. But he insists, and after bidding my hosts farewell, I go back to the hotel in great style, accompanied to my door by Mr Richaud himself. Such attention and honour for the simple traveller!

Poor Mr Richaud! He would never see our beautiful and dear France again, I heard that unfortunately he died on the ship that was conveying him back to Marseille. Now who would have thought that?

I had for a moment considered the possibility of visiting Australia; but on second thoughts, I will not make this trip now. What good would it be carrying my money to the English?

I thought about it this afternoon while watching the prisoners at work. It’s true that Australia is on the way to New Caledonia, which itself belongs to France, and I ‘d be curious to see it. But this time I will not make the long journey. I’ll see it later.

Thursday 30 August 1888

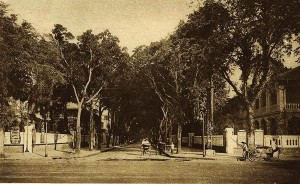

The top end of rue Catinat (Đồng Khởi street), Saigon

It’s still raining this morning, rain so heavy that it wakes me up. My watch stopped during the night, it’s just daybreak and it’s overcast. What time is it? There’s a clock in the room, but it doesn’t work… if it ever worked! I get dressed and go down to the hotel lobby: the clock at the front desk says 7.30am; it is not yet time to show up in the streets, especially in the pouring rain. Better to go back to my room and scribble a few pages in my notebook.

“Practice makes perfect,” says the proverb. I, by force of travelling through Saigon and its surrounding areas, begin to know all the carriage drivers and their vehicles.

The closed carriages here are called Malabars, probably after those in India. In Madras, Pondicherry, Singapore and Saigon, they are all alike, indeed they seem to have been built on the same pattern. They are quite unsightly when their shutters are down; but as soon as the windows are revealed, the carriages have a much nicer appearance.

As for my friends, the drivers – who don’t want to take me anywhere because they think that I want to go too far – they are of all races: Chinese, Indian, Annamite, etc, and even a few Europeans. Some Annamite drivers wear on their heads a large tortoiseshell comb and a sort of turban, the ends of which hang down on either side of their ears. Others wear on their heads a special Chinese-style hat, round in shape and made of white canvas, which somewhat resembles the hat worn by millers in Paris.

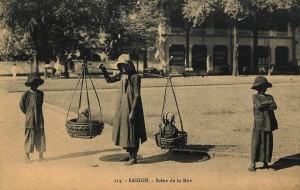

Street merchants in Saigon

Yesterday I bought a beautiful carved sandalwood panel; the wood is dark yellow in colour and it emits a very strong and pleasant smell. Here they also make sandalwood boxes, fans, statues and a thousand other knick-knacks with which we like to adorn our shelves. But as always, one must beware of counterfeits; sandalwood is a precious wood and, of course, expensive to source. Some unscrupulous traders sell objects made with the first wood they can get their hands on, adding a few drops of fragrant oil to replicate the characteristic aroma of real sandalwood.

Here in Saigon one often sees street vendors carrying on their shoulders a long piece of wood with ropes at each end supporting baskets: they are balanced like a set of scales.

Out in the villages, one sometimes sees in front of houses a box containing strings of cooked chicken, sausages and roast pork pieces, all ready to be consumed. Needless to say, these displays immediately attract the attention of many flies! This is hardly appetising, and when I see the places where this food was prepared, I have no wish to try it, I assure you! But it takes all tastes, does it not? And there are certainly plenty of takers for these snacks.

One thing I always admire here is the very graceful way in which women, lying in hammocks, cradle their babies. Although they themselves appear motionless, the hammocks rock back and forward at the discretion of the mother and the child does not take long to fall asleep. All this forms a very pretty picture, full of charm and naturalness.

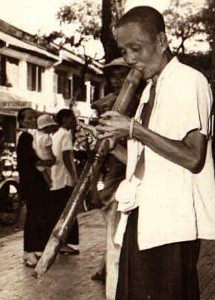

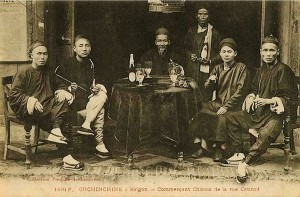

A pipe smoker in Saigon

My Chinese friends opposite have in their shop a large pipe that is smoked by everyone; when one person has finished puffing, it is passed to another, and so on around the group. It is a large wooden pipe about 1m in length, with a tiny holder in the middle where the smoker places a small amount of tobacco; once lit, this tobacco does not last long. Here they smoke just a little at a time; if a Chinese person tries to smoke a pipe like a European, he quickly feels dizzy and becomes sick. Our troopers sometimes have fun offering a tobacco pipe to a local person, who, proud of such an honour, bravely starts smoking in the European manner. But it does not take long for him to repent of his temerity!

A Chinese person will never go out on the street without his umbrella. With his long-sleeved jacket that fully covers his hands, we may believe that he has no arms. And between the bottom of his pants – which barely extend beyond the knees – to his open shoes with thick felt soles, one can see the most quaint feet and calves.

We know that every Chinese character forms a complete word and these characters are very difficult to translate because of their large number and widespread application. But something which seems even more difficult, perhaps, is to understand the spoken language. I have listened many times to conversations between the “heavenly ones,” but I find it difficult to comprehend that the same words can be pronounced with different intonations. No! decidedly, Chinese is not equal to our beautiful French language!

A heavy carriage stops in front of the hotel; it is the eau-de-soda siphon merchant, who brings ice and other provisions for the day. It goes without saying that the ice here is artificially made, and yet it is cheap: just 20 centimes per kilo. We use a great deal of it.

A late 19th century Saigon street scene

On the other side of the street, several ladies dressed in white get down from their Malabars at the door of the shoemaker, who has a certain reputation for skill: I also had the opportunity to appreciate his talent. He repaired a boot for me very efficiently and made no attempt to cheat me by making a hole in the other one.

A cloud – that’s the word – of servants invades my room; they come to clean and it’s no small matter, ah no! First, I ask them to change the bed sheets: that requires a special officer; a second brings the sheets and the first charges a third to place these on the mattress; he condescends to lend a hand while his colleague makes the bed. That’s nice of him! An “unofficial” fourth deals with the bathroom; single-handedly, he empties the bowl, changes the towel, and fills the pot with water. I am impressed!

A fifth sweeps the room and gathers all the dust into a small pile that the sixth collects carefully and carries outside, while dropping three quarters en route. There are two others who shake the rug from the balcony…. and let it drop on the head of the manager, who is smoking his cigar in the garden below! But that’s not all! The last two servants share the rest of the work to be done: one crosses his arms and the other looks on! This is what it is called domesticity. And let me tell you, they are stubborn as mules and do not want to change this routine in any way.

A young Vietnamese girl in the late 19th century

The rain’s stopped; I go back to the window and watch the world go by. I’m starting to get used to it and I can now distinguish Annamite men from Annamite women. Annamite men and women both wear loose trousers known as ke-quan and a black smock called the ke-o. But while the women wear their hair in a very small bun held with pins, the men have a much larger chignon. So here is a formula to recognise the sexes in Indochina! This formula was recommended to me by a local person: it may not be very academic, but it’s easy to remember.

I observe a Chinese hairdresser at work. He begins by unclasping the hair, which is then washed with water from a bucket. Then he carefully cleans the customer’s neck, dries the hair and rearranges it in a chignon. Finally, he takes out his razor and gives it a trim.

The hair is not worn very long; but fashion requires that it be of respectable dimensions, so the Chinese lengthen it by a braiding with silk. Thus, many of the “little masters” sport a ponytail which hangs down to the middle of their backs. Poor Chinese, who do not have the means to pay for costly silk hair extensions, use string or whatever else they can find.

After lunch, I go once more to the offices of the Messageries maritimes; but I had forgotten that it is still siesta time and find it once more closed.

Built in 1862-1863, the Sài Gòn headquarters of the Compagnie des messageries maritimes was one of the very first civic buildings constructed by the French in Sài Gòn

In that case, I, who do not take a midday siesta and do not like to waste time, will visit the Museum [at this time run by the Société des Études Indochinoises and housed in a Paris Foreign Missions Society villa at 16 rue de La Grandière, now Lý Tự Trọng]. It’s all upside down, because, according to the conservator I met at Mr de Blainville’s house, a shipment of the most valuable objects is currently being prepared for the Paris Exhibition of 1889.

This amiable civil servant shows me around the site of the new museum, currently under construction. Oh! What a beautiful monument it will be when it is completed! The city is paying for it, it is clear that here we are in a rich country that does not worry about expense when it comes to embellishments.

Leaving the museum curator, I go to buy some more trinkets in a curiosity shop: some Chinese prints, a Buddha made from camphor wood, a beautiful painted fan mounted on sandalwood and a little Mandarin carved from a piece of ivory. When I choose these objects I ask the price and am told 50 piastres (about 200 francs!).

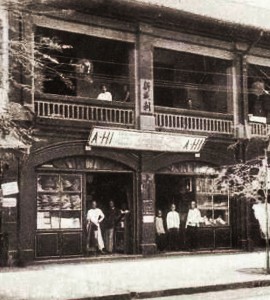

Chinese shops on rue Catinat (Đồng Khởi street), Saigon

I protest, as is fair; we discuss, we squabble a bit, the Chinese shopkeeper and I, but we finish by reaching a compromise. I take out my wallet and let him see the gold coins inside. Gold is very popular here, and when you make a payment using this currency, you’re sure to get a good bargain. The gold has the desired effect and I take all my trinkets after leaving 30 francs in the hands of the shopkeeper, who earlier had asked me for 200. I’m sure that in Paris these items would cost no less than 300 francs!

By now, the gentlemen at the Messageries maritimes must surely have finished their nap, so I return to the shipping office and at last I find it open. I buy a ticket to Yokohama, a place I intend to visit before returning to France. The office is located on the quayside, opposite the shipping wharf, and is quite far from the city. On the quai des Chinois are the consulates of both Britain and Germany; their buildings touch each other; and today there is even a German warship in the port. Here, our good friends across the Rhine are forced, willy-nilly, to admire the wealth and prosperity of our beautiful colony; they certainly have no equivalent.

Back at the hotel, I prepare myself for a cold bath, as always. But I’ve found that the hydrotherapy unit, which did so much to gain my admiration when I first arrived, doesn’t always work properly. When I go to turn on the stopcock, I succeed only with great difficulty and end up showering myself a little more than I would have desired. I laugh, of course, because when travelling, this kind of thing can be expected.

Chinese merchants on rue Catinat (Đồng Khởi street), Saigon

I get dressed and go back to my room. Right under my window, a Chinese woman walks by, wearing a costume of many colours, with a pearl necklace and flowers in her hair. In front of her walks a servant; another follows.

Just then, a fight breaks out in the shoemaker’s shop opposite: the “heavenly ones” are very funny when they argue; the sound of their voices is dry and brittle. I see that by the time they come to blows; one of them has wrapped braid around his head to avoid his opponent seizing his hair. Fortunately, their assistants manage to restore order.

Going down to the dining room for dinner, I observe one of the waiters removing a toothpick from the table, using it and then, when he sees me watching him, putting it back again! That’s good to know; now I will avoid touching these little implements! The manager, with whom I share my observation, does not seem surprised; he tells me that, despite all his efforts, he has been unable to make his staff understand that reusing toothpicks is unhygienic.

To read part 5 of this serialisation click here

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.