The Nguyen Van Cua Imprimerie de l’Union building at 49-57 Nguyễn Du

This article was published previously in Saigoneer http://saigoneer.com

Located close to the Saigon Post Office, the unassuming two-storey white shophouse building at 49-57 Nguyễn Du was once the headquarters of one of the most successful colonial-era printing companies.

In the early days of the colony, the Cochinchina administration set up its own government printing works to handle the publication of all official French government publications, including the Annuaire de Cochinchine Française and the Annuaire de l’Indo-Chine française.

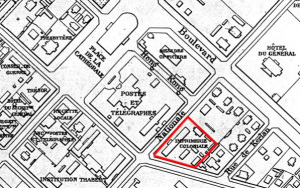

The Imprimerie coloniale, established in 1867 on the site of today’s Intercontinental Hotel, as indicated on a map of 1891

Established in 1867 on the site of today’s Intercontinental Hotel and run by a high-ranking government administrator, this institution was initially named the Imprimerie impériale, but later went by the alternative names of Imprimerie nationale or Imprimerie coloniale.

However, following the replacement of the early Admiral-Governors by a civil administration in 1879, the printing market was opened up to competition from private companies, leaving the poorly-funded Imprimerie nationale unable to compete effectively. It eventually closed in 1904.

According to a report in the Moniteur de la papeterie française et de l’industrie du papier of 15 January 1904, “The Printing Office of Cochinchina has been abolished. The equipment was old, worn, and required replacement; the Governor recognised that the private printing companies were sufficient, so he decided to close the Imprimerie nationale in order to save public money, while arranging for the fair dismissal of staff.”

In subsequent years, both public and private books and documents were printed by a variety of independent printing companies, including the Imprimerie Saigonnaise, the Imprimerie Commerciale Ménard et Rey and its later offshoot the Imprimerie Rey, Curiol et Cie, the Imprimerie nouvelle A Portail and the Imprimerie Moderne.

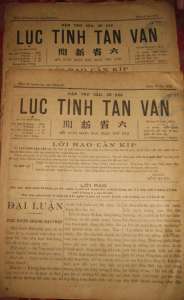

In the 1920s, the Imprimerie de l’Union printed the Lục Tỉnh Tân Văn newspaper

However, by the 1920s, one of the best-known and most successful of Saigon’s printing enterprises was Nguyễn Văn Của’s Imprimerie de l’Union, based initially at 13 and later at 57 rue Lucien Mossard (modern Nguyễn Du street). It printed the newspapers L’Écho annamite: Organe de défense des intérêts franco-annamites, L’Eveil économique de l’Indochine and later L’Ere nouvelle: Organe bi-hebdomadaire du Parti travailliste annamite, along with journals such as Pháp Viện Báo: Revue judiciaire franco-annamite and a wide range of Cochinchina, Saigon municipal and provincial government publications. The company also took over the printing of Lục Tỉnh Tân Văn (“Six Provinces News,” founded 1907), one of the earliest newspapers to use the Vietnamese quốc ngữ script.

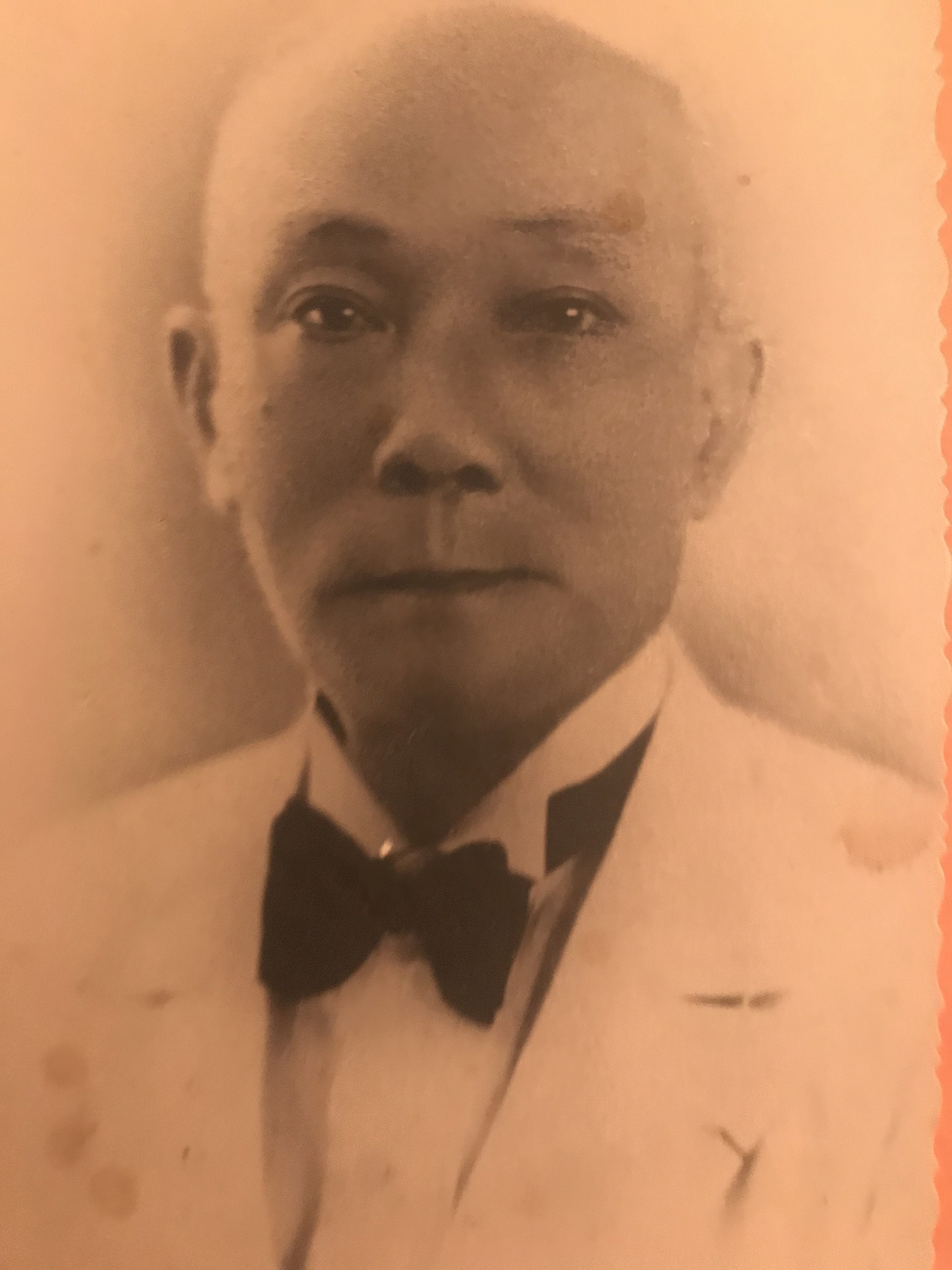

Regarded as one of the leading Vietnamese intellectuals of his day, proprietor Nguyễn Văn Của acquired French citizenship, was elected as a Colonial Councillor and could frequently be found mixing amongst the high society of Cochinchina. He also became the owner of a 288-hectare plantation in Long Thành, Biên Hòa, and an active member of the Association des planteurs de caoutchouc de l’Indochine (Indochina Rubber Planters’ Association).

In 1925, Của was elected president of the committee tasked with raising funds for the statue of Pétrus Trương Vĩnh Ký and succeeded in raising 90,000 Francs to pay for the construction and installation of the monument. Significantly, when it was formally installed in 1928 behind the Cathedral, it was Của himself who delivered the eulogy.

Nguyễn Văn Của was also an active member of the Société des Études Indochinoises, and in 1927 the Société made him the president of the subscription committee they had set up to raise funds for the purchase of naval pharmacist Dr Victor-Thomas Holbé’s Asiatic art collection.

The words “Nguyen Van Cua” and “Imprimerie de l’Union” are still visible on the upper façade of the building

Của’s fundraising skills and extensive network of contacts ensured that Holbé’s priceless art works became the core collection of the new Musée Blanchard de la Brosse (opened in 1929), now the Hồ Chí Minh City History Museum.

Của’s eldest son Nguyễn Văn Xuân also became a naturalised French citizen, attending the prestigious Collège Chasseloup Laubat Laubat (now the Lê Quý Đôn Secondary School) and later embarking on a successful career in the French army, rising to the rank of lieutenant-colonel.

When he died in May 1941, Nguyễn Văn Của was given a grand funeral which was attended by many of the colony’s great and good. A few days later, in a long article in the Écho annamite newspaper, the President of the Chamber of Agriculture J Mariani gave a long eulogy describing Của as “a fine example of a self-made man” and “a model partisan of the Franco-Annamite union.”

The Nguyen Van Cua Imprimerie de l’Union building is a two-storey building which originally incorporated commercial spaces at ground floor level and family accommodation above. It has survived intact until the present day, with the words “Nguyen Van Cua” and “Imprimerie de l’Union” still visible on its upper façade, but it is now in very poor condition. Sadly, it stands on the so-called “Gold Land” block enclosed by Đồng Khởi, Lý Tự Trọng, Nguyễn Du and Hai Bà Trưng streets, which, according to newspaper reports, will soon be redeveloped to accommodate “services, culture, luxury hotels, finance offices and exhibition areas.”

Nguyễn Văn Của, family photograph courtesy of his great-great grandson M Jean Xuan Chevalier

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.