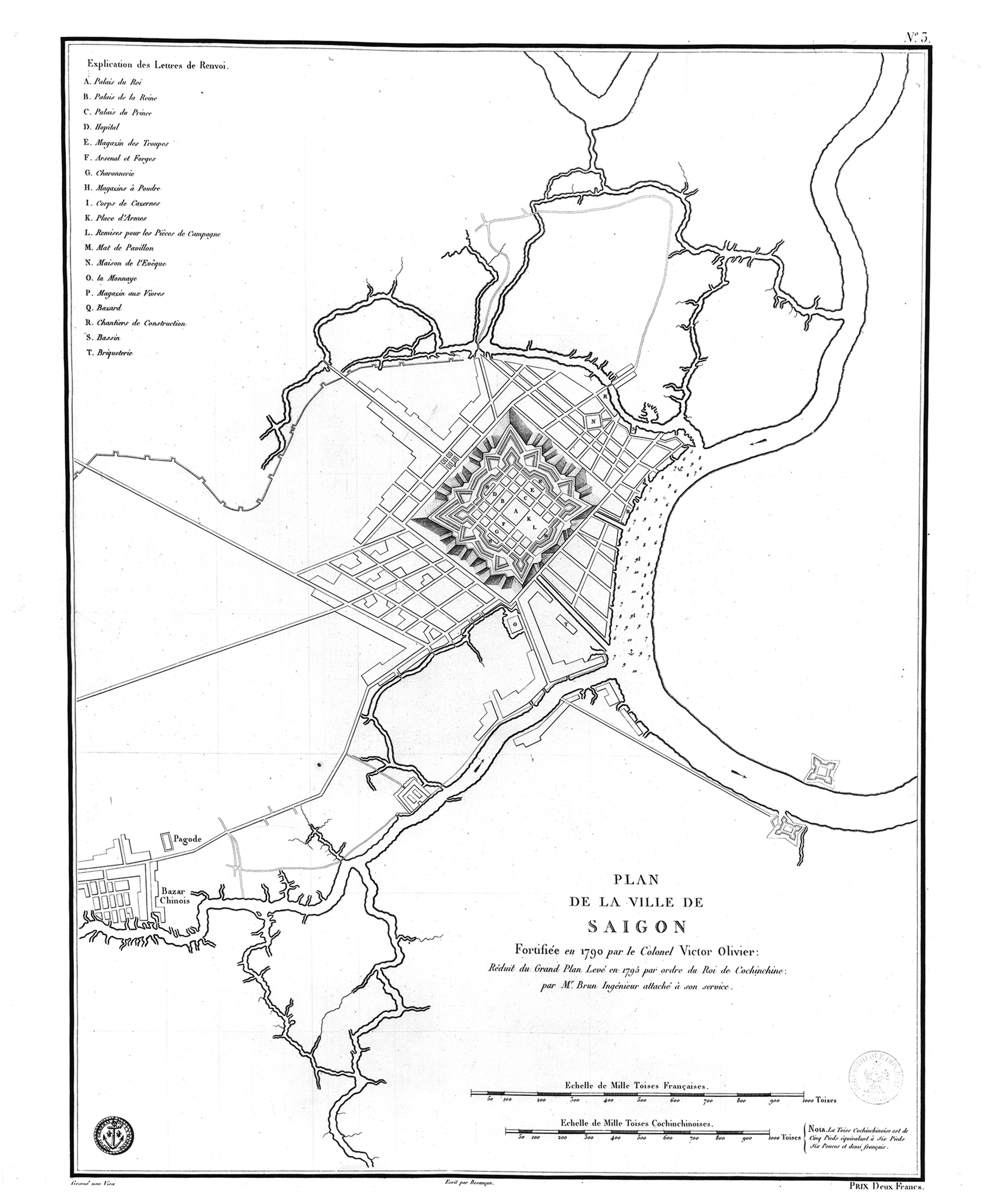

Plan of the City of Saigon, fortified in 1790 by Colonel Victor Olivier, reduced from the Great Plan drawn in 1795 by the order of the King of Cochinchina by M. Brun, Engineer in his service

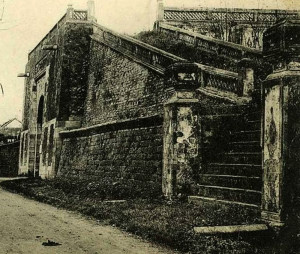

As the foundations for the Catinat Building were being laid in January 1926, large sections of bastion wall from the first Gia Định Citadel of 1790 were uncovered. On 8 February 1926, the Écho annamite newspaper published this fascinating article by Vietnamese scholar Ung-Hue on the history of Vauban military architecture in Cochinchina.

Since the discovery of the remains of the citadel built in Saigon according to the Vauban system by French officers in the service of Gia-Long, there has been much interest in the fortifications of this nature which were built in Cochinchina.

Undoubtedly, the Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Hué, edited by R. P. Cadière, has made a valuable contribution to the history of our country. But so far it has not published any study on the Annamite armies or on the military arts of Annam. However, as Napoléon III once said, “The history of peoples is largely the history of its armies.”

Undoubtedly, the Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Hué, edited by R. P. Cadière, has made a valuable contribution to the history of our country. But so far it has not published any study on the Annamite armies or on the military arts of Annam. However, as Napoléon III once said, “The history of peoples is largely the history of its armies.”

While waiting for the Association des Amis du Vieux Hué, or perhaps even the Société des Etudes indochinoises de Saigon, to take responsibility for undertaking this work as part of their ongoing studies of Indochinese archaeology, history and philology, I think it may be interesting to gather together some information on the ancient “Vauban” citadels which were built in Cochinchina by French officers in the service of Gia-Long, or by their Annamite imitators.

Let’s recall first of all that King Louis XIV’s military engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707) perfected the methods of fortification developed by his predecessors; and that, better than any of them, he knew how to adapt his citadels to the terrain in which they were built. Also, although one speaks generally of three Vauban “systems,” most textbooks admit that the illustrious engineer never strengthened two fortresses in the same manner, and that it was his successors who invented this threefold classification simply to facilitate its teaching.

Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, Seigneur de Vauban and later Marquis de Vauban (1633-1707)

Vauban also made improvements in the methods of attacking a citadel, developing his famous “parallel trench” system to ensure the decisive superiority of attackers over defenders. It was in order to make a citadel able to resist the maximum onslaught that he constantly studied methods of attack and then modified the fortifications accordingly. It was he who pioneered using the topography of the land when locating a fortress, and who carefully positioned the outer and inner walls, projecting bastions and lines of half-moon batteries, hiding his citadels behind massive fortifications and making them practically invulnerable.

The publication of plans and drawings of the Vauban citadels constructed in Cochinchina have, from a historical and military point of view, an importance of the first order. There no doubt exist many documents of this nature in the Directorate of Artillery and the Saigon Cadastre (Land Registry) Service. For example, I reported in a previous article on the plan of the Saigon citadel built by Olivier and Lebrun, which came from the collection of M. Bouchot.

That plan, which is now kept at the Cadastre, is a copy in reduction of a drawing found by M. Pont, former head of that service. It is a work in which the name of the draftsman has unfortunately been omitted. A second copy was presented by M. Pont to the Société des Etudes indochinoises when he was president of that society; it is probably this copy which was reproduced by George Dürrwell in his book Ma chère Cochinchine, trente années d’impressions et de souvenirs, février 1881-1910 with the following caption: “Map of the City of Saigon, fortified in 1790 by Colonel Victor Olivier, reduced from the Great Plan drawn in 1795 by the order of the King of Cochinchina by M. Brun, Engineer in his service.”

Apart from this plan, there also exist drawings of five other Annamite citadels or fortified works built in Vauban style. These are the fortresses of Bien-Hoa, Ben-Ca, Phuoc-Tan, Long-Thanh and Tan-Uyen. They were executed to 1:2000 scale in 1854 by Marine Infantry Lieutenant Cullard and signed by Corporal Maquard.

Apart from this plan, there also exist drawings of five other Annamite citadels or fortified works built in Vauban style. These are the fortresses of Bien-Hoa, Ben-Ca, Phuoc-Tan, Long-Thanh and Tan-Uyen. They were executed to 1:2000 scale in 1854 by Marine Infantry Lieutenant Cullard and signed by Corporal Maquard.

No monument “à la Vauban” was built in Can-Tho. After the occupation of Bien-Hoa, Gia-Dinh, Dinh-Tuong (the former name of the province of My-Tho) and Vinh-Long by French troops, a mandarin of An-Giang (Chau-Doc) was ordered by the Court of Hue to build two store-fortresses (bao) in order to keep the precious objects of the provinces safely and also to store food for contingencies. Thus, two bao were erected, one in the village of Long-Thanh (Sadec), under the name of Bao-Tien (forward store), and the other at village of Dinh-Hoa (Can-Tho) under the name of Bao-Hau (Rear store). These works were square-shaped buildings built from masonry, but today only barely-recognisable ruins remain. They served for some time as a refuge for troops and Annamite irregulars who resisted the French army.

At Chau-Doc, in the village of Long-Son, canton of An-Thành, one may find the remains of an ancient citadel built in 1838. It had not yet been completed when a Cambodian revolt forced the officers of Minh-Mang to abandon it and flee to the capital of Chau-Doc, where they built a large redoubt, now destroyed. That citadel, defended to the north by the Rach Cai-Vung, was surrounded on its other sides by ditches 20m wide and 2.50m deep. Within what is left of the ancient walls, we may still see three platforms without any special character.

At Chau-Doc, in the village of Long-Son, canton of An-Thành, one may find the remains of an ancient citadel built in 1838. It had not yet been completed when a Cambodian revolt forced the officers of Minh-Mang to abandon it and flee to the capital of Chau-Doc, where they built a large redoubt, now destroyed. That citadel, defended to the north by the Rach Cai-Vung, was surrounded on its other sides by ditches 20m wide and 2.50m deep. Within what is left of the ancient walls, we may still see three platforms without any special character.

Located some distance from the village of Vinh-Lac, on the edge of the Ha-Tien Canal, we may also note the shapeless remains of an old earthen fort which was built in around 1820 to monitor the digging of the canal.

In Ha Tien itself, there are also traces of a citadel which was built, it seems, by Mac-Cuu; but the few sections of wall which remain are in such a state of decay that it is impossible to work out the shapes or indeed dimensions this citadel could have had.

The citadel of My-Tho (formerly Dinh-Tuong), like that of Saigon, was built in the reign of Gia-Long by Olivier and Lebrun. A plan was drawn up in 1873 by M. Pont, when he carried out a cadastral survey of that province.

At Sadec, there exists the foundation of the old earthen fortress in the village of Long-Hung, at the mouth of the Rach Nuoc Xoay. The Nguyen-Trao-Thiet-Luc reports that Nguyen-Anh (later Gia Long) took refuge there during his war with the Tay-Son.

At Sadec, there exists the foundation of the old earthen fortress in the village of Long-Hung, at the mouth of the Rach Nuoc Xoay. The Nguyen-Trao-Thiet-Luc reports that Nguyen-Anh (later Gia Long) took refuge there during his war with the Tay-Son.

Two fortresses existed in Tay Ninh, that of Quang-Hoa in the village of Cam-Giang, and that of Bau-Don in the village of Phuoc-Thanh. The latter was located exactly at what is now km 63 on Route Coloniale No 1. Nothing now remains of either fortress, apart from some light remains which are now completely covered by high grass and forest.

The citadel of Vinh-Long was demolished in 1877.

The book Dai-Nam-Nhut-Thong-Chi or “General Description of the Great Annam,” written in Chinese characters, includes a plan of all the citadels built in the reign of Gia-Long by Olivier de Puymanel, who is better known under the names of “Ong Tin” or Colonel Olivier.

The citadel of Saigon, the ruins of which were discovered in January 1926, was destroyed following the revolt of Le-Van-Khoi, adopted son of Le-Van-Duyet, who had served as Viceroy of Cochinchina under Gia-Long and Minh-Mang.

The citadel of Saigon, the ruins of which were discovered in January 1926, was destroyed following the revolt of Le-Van-Khoi, adopted son of Le-Van-Duyet, who had served as Viceroy of Cochinchina under Gia-Long and Minh-Mang.

J. Silvestre published the story of this revolt in the Annales de l’Ecole libre des Sciences politiques. Without adding anything to what we might call the “famous lines of history” surrounding the Great Eunuch, our former Director of Civil and Political Affairs gave us a more complete and finished picture of the story. His article contains many details for which we may look in vain in biographies of Le-Van-Duyet, and these details are of the kind which help us form a better idea of the character of both the men involved and the era in which they lived. J. Silvestre has borrowed mostly from the writings of contemporaries of Le-Van-Duyet. The judicious use he makes of these documents gives his story the advantage of dramatic colour, transporting the reader back to the early 19th century to experience the events he recounts. The passage dedicated to Le-Van-Khoi is particularly remarkable in this respect.

We know that after the death of Le-Van-Duyet in August 1832, Emperor Minh Mang ordered the governor of Saigon to pronounce, by posthumous judgment, on the conduct of Le-Van Duyet. From the beginning of this strange process, the entire family of the late Viceroy were arrested and incarcerated, on the pretext of questioning. Among them was Khoi, a Tonkinese of Muong ethnic descent. Involved in a rebellion and taken prisoner by the troops of Le-Van-Duyet after having put up a very brave fight, he had been saved from punishment by the Viceroy, who recognised his courage and uprightness. From that time onwards, Khoi attached himself to the fortunes of his benefactor, whom he followed in Saigon, eventually being promoted in 1832 to the grade of Lieutenant Colonel.

Minh-Mang’s posthumous investigation into Le-Van-Duyet continued for some time. On the occasion of the Viceroy’s death anniversary, Khoi asked permission to go to his private home to celebrate the ritual ceremonies there. The chief justice agreed, placing him under the escort of several soldiers.

Minh-Mang’s posthumous investigation into Le-Van-Duyet continued for some time. On the occasion of the Viceroy’s death anniversary, Khoi asked permission to go to his private home to celebrate the ritual ceremonies there. The chief justice agreed, placing him under the escort of several soldiers.

At this time, it was customary for people recruited for military service to be transferred from their own province to another, or for those condemned to exile outside their province to be conscripted into armies elsewhere. So it was that the soldiers charged to monitor Khoi were his countrymen who had been recruited from Tonkin, and they proved more than ready to support him. Khoi took the opportunity of the Viceroy’s death anniversary to gather his friends and other people loyal to the memory of Le-Van-Duyet and armed them. On the next night, they surprised and killed the main mandarins of Saigon.

With all of the Tonkinese soldiers rallying around their leader, many other people in Cochinchina embraced Le-Van-Khoi’s cause. From that moment, Khoi found himself master of Cochinchina. He set up a government, of which he became the leader with the title of Generalissimo. But the court of Hue quickly assembled an army to quell the insurgency; at the same time, it bought with money the betrayal of some rebel leaders, and suddenly Khoi found himself besieged in the Saigon citadel, awaiting the help he had requested from Bangkok.

At the end of 1833, the royal army began the siege of Saigon. The city was defended by about 2,000 soldiers. Early in 1834, the Siamese arrived and easily captured Ha-Tien and Chau-Doc. But they then disbanded and proceeded to plunder the country. Shamefully beaten by the Annamites, they hastened back across the border with their booty.

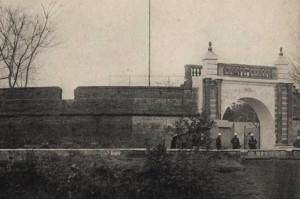

The siege of Saigon lasted until 1835. In the seventh month, the royal army made a supreme effort, For three days and three nights, Minh-Mang’s artillery bombarded the citadel. Then at 4am on the 10th, the firing suddenly stopped and a massive assault was launched from all sides.

The siege of Saigon lasted until 1835. In the seventh month, the royal army made a supreme effort, For three days and three nights, Minh-Mang’s artillery bombarded the citadel. Then at 4am on the 10th, the firing suddenly stopped and a massive assault was launched from all sides.

Despite the desperate resistance of the besieged, the citadel was taken and its defenders were either killed or captured.

Order was restored in Cochinchina, permitting the case against Le-Van-Duyet to resume. His tomb was razed, and over the ruins was erected a pillar surrounded by chains, together with this contemptuous inscription: “Here lies the eunuch who resisted the law.”

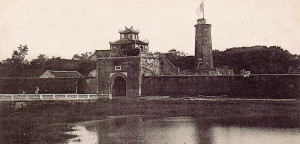

The citadel of Saigon was destroyed and replaced by another one of smaller dimensions. It was that smaller citadel which was taken in 1858 by Admiral Rigault de Genouilly.

Ung Hue

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.