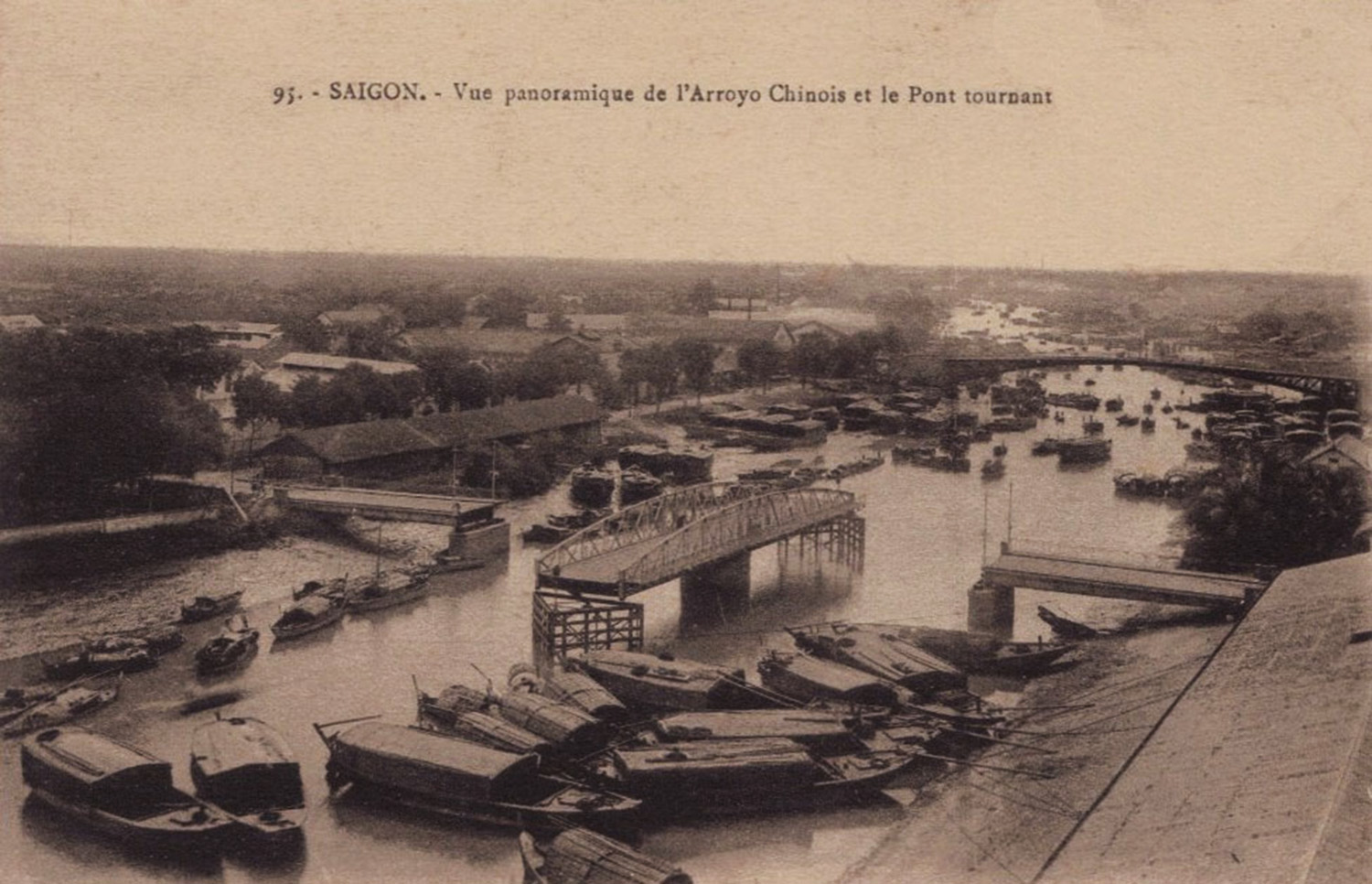

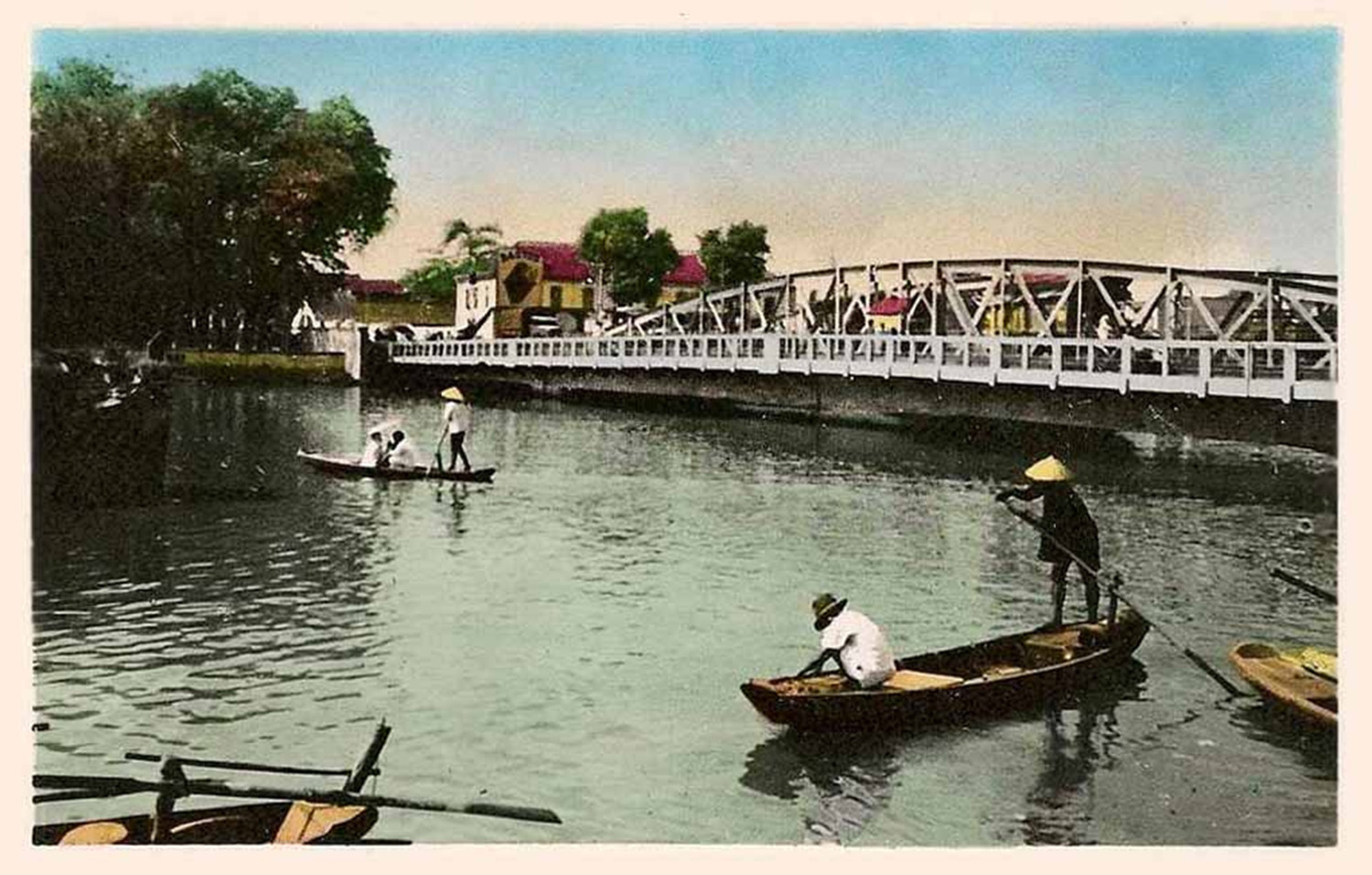

The Swing Bridge in the early 20th century

This article was published previously in Saigoneer http://saigoneer.com

Many people are familiar with Eiffel’s Pont des Messageries maritimes (Cầu Mống), yet few remember its neighbour the Pont tournant (Swing bridge), which was built by the Eiffel successor company Levallois-Perret in 1902-1903 and stood close to the entrance to the Bến Nghé creek for nearly 60 years.

Saigon’s “Malabar” drivers found the ramps of Eiffel’s pont des Messageries maritimes too steep and dangerous for their horses

In the early colonial period, the need to permit unimpeded access to the arroyo-Chinois (Bến Nghé creek) by freight barges of all sizes precluded the construction of a street-level bridge.

Instead, the authorities commissioned the construction of a grand arched bridge, Eiffel’s pont des Messageries maritimes, to connect the port with the city. Though praised for its elegant design, Eiffel’s bridge was disliked by “malabar” drivers, who complained that the access ramps were too steep and dangerous for their horses.

In 1895, plans were drawn up to install a flat swing bridge close to the mouth of the creek. However, in the following year these plans were abandoned in the face of vehement opposition from Chợ Lớn’s merchant ship owners, who feared that the new bridge would block shipping access.

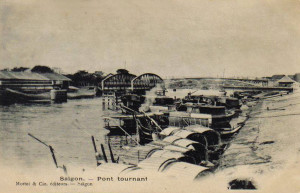

Another early 20th century view of the Swing Bridge

The swing bridge project was revived in 1900, when the French authorities began planning the new canal de Dérivation (the Tẻ Canal in Khánh Hội) to provide merchant shipping with an alternative entrance to the arroyo Chinois.

At this juncture, the Saigon-Mỹ Tho railway line operator Société générale des tramways à vapeur de Cochinchine offered to part-fund the construction of the bridge, in exchange for permission to install on it a railway track to carry freight trains across the creek to the port.

In the second volume of his Situation de l’Indo-Chine de 1902 à 1907 (1908), Jean Baptiste Paul Beau describes the events which followed:

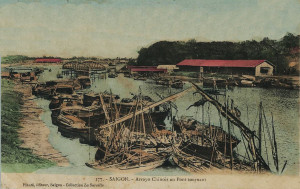

The quai de Belgique side of the Swing Bridge in the 1920s

“The Pont tournant (Swing Bridge) over the arroyo-Chinois in Saigon was included in the programme of work set out in the decree of 12 November 1900 to improve the commercial port of Saigon. It was built by the Société de constructions de Levallois-Perret, under the terms of a contract approved on 6 July 1901.

Set a little above street level, it connects the city with the port. It gives passage to a railway, carriages and pedestrians, while ensuring river traffic on the arroyo-Chinois by means of a turning span measuring 49.20m in length, supported by and pivoting horizontally on a central pillar. Each of the two fixed sections at either side measure 19.194m in length.

The 7.10m wide bridge incorporates a 5.10m road flanked by two pedestrian lanes of 1m each.

The work began in January 1902 and was completed in July 1903.

Expenditure amounted to 382,755.12 francs for the work by the company and 11,166.12 francs for associated works. These included, notably, the demolition of part of the Customs warehouse and its reconstruction in another part of the quayside, as well as the development of approach roads to the bridge.”

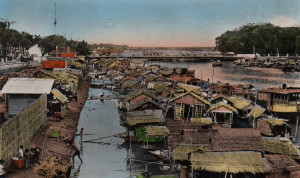

A “colorised” view of the Swing Bridge from the pont des Messageries maritimes in the 1920s

From the outset, the new bridge – known in Vietnamese as Cầu Bắc Bình Vương – attracted much criticism. Despite the opening of the canal de Dérivation in 1906, many merchant ships still used the original entrance to the arroyo Chinois. They found the central pier hazardous to navigation and the channels either side of it too narrow to accommodate the large number of vessels entering and leaving the creek.

However, most complaints about the new bridge focused on its pivoting mechanism. In his 1911 book Ma chère Cochinchine, trente années d’impressions et de souvenirs, février 1881-1910, George Dürrwell comments:

“The bridge swings very badly. Some even claim that it doesn’t work at all, but those are grumpy and biased people who deserve no credit. I can say, indeed, that I saw it open at least once, at a practical time which permitted the free movement of the public. But, as the saying goes, ‘One swallow doesn’t make a summer.’ This unfortunate bridge has thus acquired, from its inception, a true local celebrity; and the rivers of ink that have been spilled talking about it are certainly more tumultuous than the waves of dirty water which agitate the river over which it was thrown.”

Another “colorised” view of the Swing Bridge from the pont des Messageries maritimes, taken after it was transformed into a fixed bridge in 1930

Twelve years later, the Swing Bridge was still the talk of Saigon. The following is taken from an editorial of 14 January 1923 in the newspaper L’Eveil économique de l’Indochine:

“A by-law prescribes that the Swing Bridge must be open from two hours before until two hours after the arrival of maritime courier vessels. Why then yesterday, despite the arrival of the Cordillère at 1pm, did the swing bridge remain stubbornly closed to road traffic until 3pm?

Who doesn’t know about this famous Swing Bridge? Whenever one wants to cross it by car, it’s open to boats, and whenever a boat appears, it’s open to cars.”

The editorial went on to suggest the demolition of both the pont des Messageries maritimes and the Swing Bridge and their replacement by “a transporter bridge, built strong enough to carry heavier trucks and trams.”

An early 1930s view of the Swing Bridge after it was transformed into a fixed bridge

By this time, the canal de Dérivation (now the Kênh Tẻ) had long taken over as the main water gateway to Chợ Lớn, and in 1930 the authorities voted 4,100 piastres to transform the Swing Bridge into a fixed structure. Thereafter, only the smallest of boats could pass underneath it.

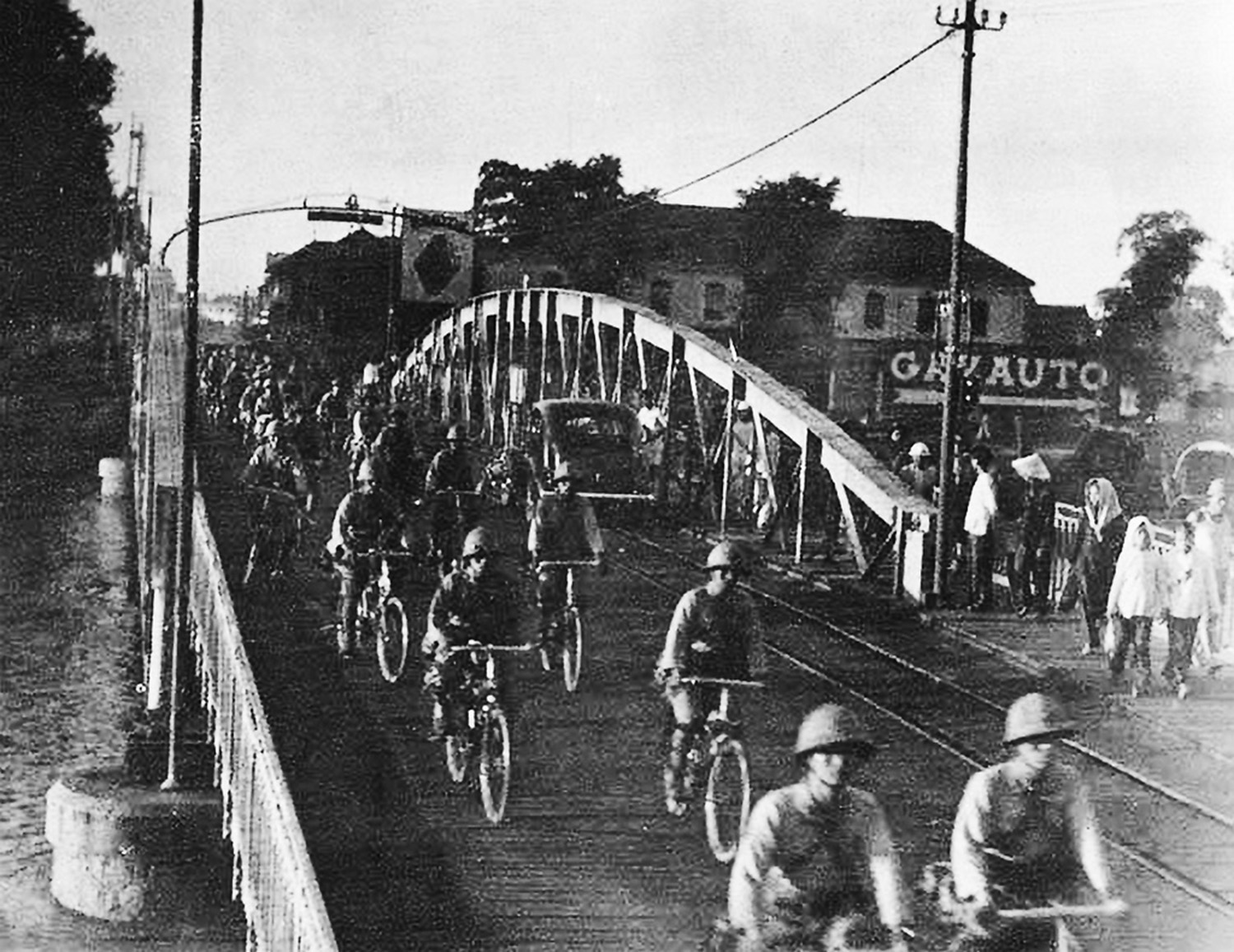

One of the most famous pictures of the now fixed Swing Bridge was take in July 1941 when, after landing at the port, occupying Japanese forces crossed it on bicycles to enter Saigon.

Following the return of the French after World War II, a new separate rail lane was added to the east side of the bridge in order to keep rail traffic away from the road vehicles using the central lane.

The former Swing Bridge survived until 1961, when it was demolished and replaced by the reinforced concrete Khánh Hội Bridge (Cầu Khánh Hội). That in its turn was demolished in 2009 to make way for the current structure.

Japanese forces crossing the bridge to Saigon on bicycles in July 1941

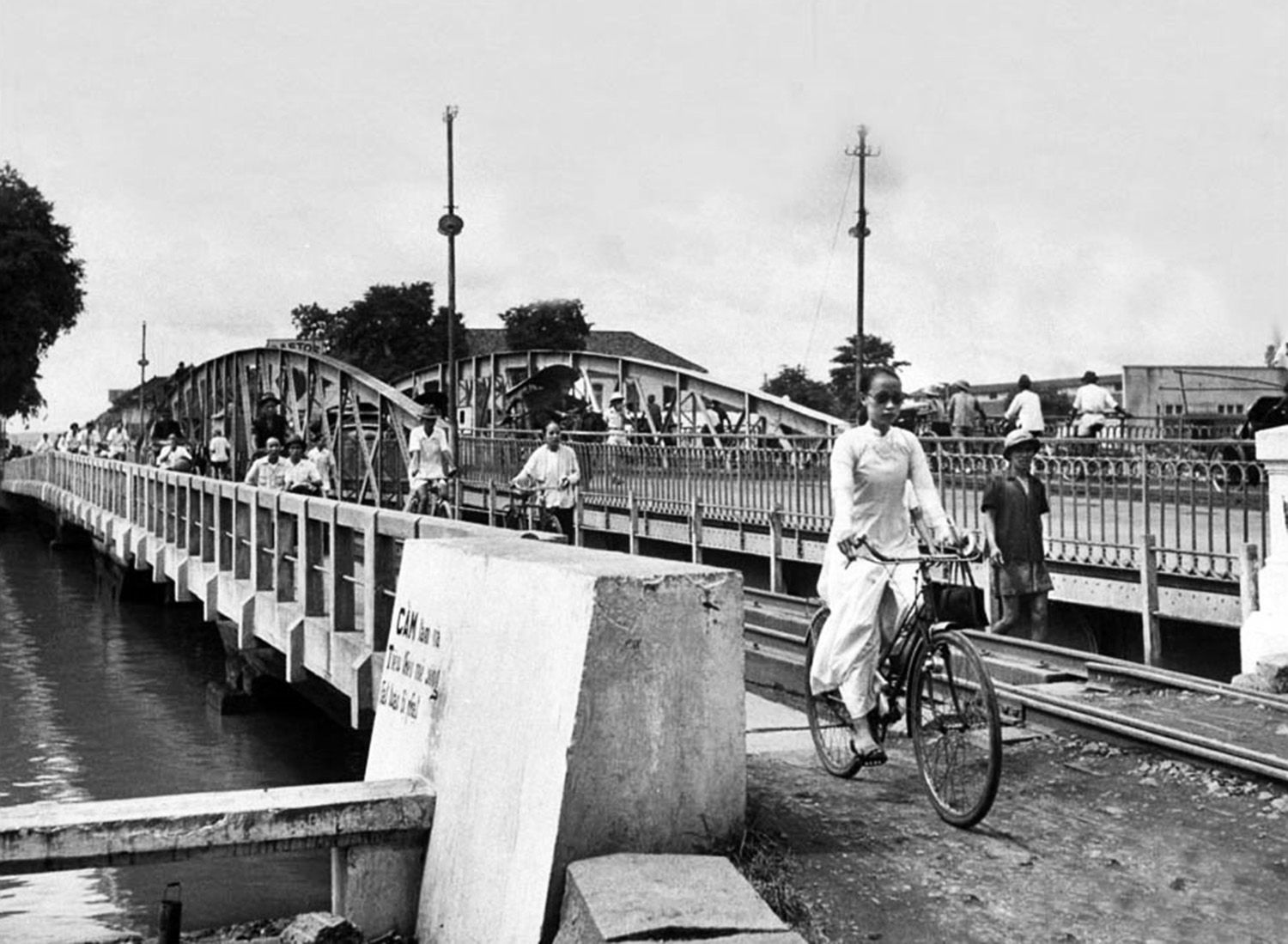

The new separate rail (and pedestrian) lane is visible in this photo of the bridge in July 1948 by Jack Birns

The former Swing Bridge in the early 1950s

The Khánh Hội Bridge which replaced the former Swing Bridge in 1961

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.