Chợ Lớn Central Market

This is the second of two excerpts from La Cochinchine française (1883), one of several works on colonial Indochina written by Saigon magistrate Raoul Postel.

To read part 1 of this serialisation, click here.

The Chinese City of Cholon

To get to Cholon, two roads are frequented by preference: that of the route des Mares and that of the Arroyo-Chinois.

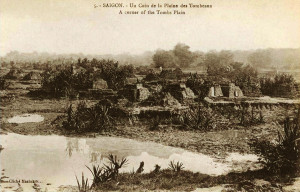

The countryside around Saigon

The route des Mares continues west from the rue de Lagrandière [Lý Tự Trọng]. On the right as we head for Cholon is the Plain of Tombs; and on the left, a long strip of rich and fertile land. Here, on the outskirts of Saigon, are the former garden houses of the Annamite mandarins. Located one after the other, the ruins of their opulent pleasure houses are now hidden in the undergrowth. All that now remains are the trees which once adorned these delicious retreats: guava and grapefruit, mango and mangosteen, curious banyan, beautiful tamarind, slender areca. But European construction in this area is gradually making them disappear.

Further along, the road runs past the government Stud Farm and a former artillery park, now an Annamite army barracks known as “les Mares” because of the two small ponds which adorn each side of its main entrance – in one of these the mandarins kept fish, and in the other crocodiles. There were once two royal pagodas here, which were celebrated in the annals of the country. Here, in 1783, a French soldier who had given his life in defence of King Gia Long was buried amidst great pomp in the first pagoda; while in the other, Gia Long himself married the woman who later became the mother of his successor, King Minh Mang. After passing this place, this road offers nothing else of interest. It has a total length of 6 kilometres.

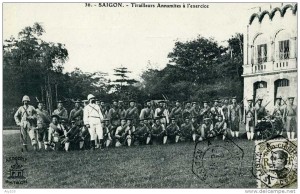

The “Camp des Mares” army barracks

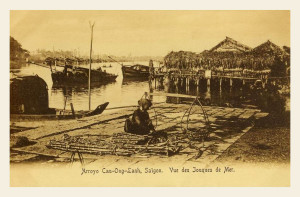

The arroyo-Chinois [Bến Nghé creek], so animated, so crowded, and so graciously designed to provide a pleasing contour to the eye, is the second route to Cholon and the most convenient one for those who fear the dust and heat.

Taking this route, it becomes apparent that there are few cities which can offer prettier scenery than Saigon. Along the riverbank, lines of houses on stilts advance over the water, serving as quays for the residents. Narrow canals lead away behind mountains of greenery.

On the right, we see the huge roof of the Cau-Ong-Lanh Chinese Theatre, of which I will say more later. On the left, a little further upstream, we see the arroyo-de-l’Amphytrite (Ong-Lanh). Near this creek, set back amidst a grove of areca and coconut trees, on may see the modest spire of the Cho-Quan Church. Nearby is the hospital of this pretty village, a hospital devoted to Asians. It is connected to the Pagode des Mares by a thousand paths, each one shaded and cool.

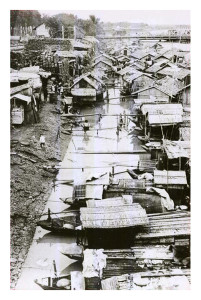

The banks of the arroyo-Chinois in Chợ Lớn

The arroyo-Chinois is as useful for the merchant as it is pleasant for the tourist to travel on. It is always packed with boats bringing goods from the vast storehouses of Cholon to Saigon for export. In the past, a bridge located at the entrance of the arroyo-Chinois prevented larger sea junks from accessing the creek and sailing down to Cholon. However, some years ago this bridge collapsed and happily we have now replaced it with a rotating iron bridge, built in France.

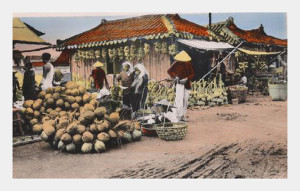

If we now enter the city of Cholon by one of the branches of this beautiful creek, we can admire its wide streets lined with solid and well-built one-storey houses, and the crowded quaysides with their shophouses packed with countless treasures, collected through the active and patient commerce of the Chinese. Cholon is their city, and in a very short time it has undergone considerable development.

Commercial freedom was the only way to achieve this rapid development. By breaking the old barriers, we succeeded in permanently settling the Chinese in this, their city of choice. It is true that some of them have been established here for more than a century. Many currently own land and houses. They understand fully the scope of the measures we have taken in their favour, which are intended to facilitate their efforts. And they profit greatly from them.

Boats on the arroyo-Chinois

The real name of Cholon is Taï-Ngon, the Chinese name which the Annamites transformed into Saï-Gon. Today, the Chinese city is known only by its indigenous name Cholon, which means “big market.”

When we French first arrived in Cochinchina, Cholon was a dirty city, with dark and unhealthy homes clustered alongside narrow and winding streets. Its makeshift bridges, impassable to carriages, were also inconvenient for the feet of Europeans. Roads were often flooded by the tide, and house fronts were receptacles of filth. We created wide and airy streets, developed the docks, dug a new canal, rebuilt or restored the houses along the water’s edge, built bridges and bounded properties, cleaning and brightening up the city. Through our efforts, Annamite suburbs were transferred to new locations. Now, in the middle of the city, there stands an immense arcaded City Market with a tiled floor, courtyards and exterior sidewalks. Today we can finally move at ease in this bustling centre.

Thanks to the connecting arroyos and canals, junks, sampans and fishing boats can enter the city from all directions and unload their goods on the wharfs, where they can be transferred directly into the shophouses. A special steam boat service also runs back and forward every half-hour between Cholon and Saigon, carrying travellers and their goods.

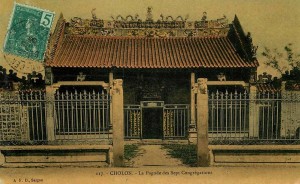

The Pagode des sept congregations in Chợ Lớn

The city is divided into five districts, each with a Chinese, Minh Huong and Annamite chief, which has had the effect of homogenising the population of these three very disparate elements, and also of encouraging the Annamites to become more interested in the commercial development of the city. Our Inspector of Native Affairs is responsible for the supervision and control of the chiefs of the Chinese congregations, and he is also responsible for justice and tax collection. When I left the colony, the pressing question was whether or not Cholon could be provided with an exclusively Asian city council. But, from the point of view of future development, I think that this would be an unfortunate measure.

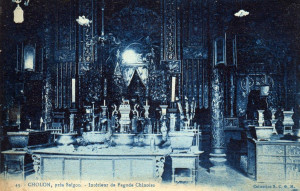

The greatest attraction of Cholon, as far as the European is concerned, is its very large number of pagodas and temples. This city is the true “boulevard of Buddhism” in Cochinchina and we will now visit three of its most famous places of worship.

The first is the Kuang-Ti [Quan Công or Guānyǔ] pagoda, dedicated to the warrior deity. From the outside, it looks like all the rest of its peers. A high brick wall surrounds it on all sides, at the front of which stands a monumental three-entrance gate, the upper compartments of which are decorated with ceramic bas-reliefs: the one in the centre is the highest of the three, and each is covered with a light roof of tubular tiles, designed to protect against heavy rain.

The Nghĩa An (Cháozhōu) Assembly Hall, known locally as the Quan Đế Temple (Miếu Quan Đế) or the “Mr” Pagoda (Chùa Ông)

Within the walls, located in the centre of a vast courtyard, are two long buildings. One wing is the temple, while the other is reserved for temple officials. Between the two buildings is a tall and thin carved wooden column supporting a bronze carved cornice, in which is housed a deformed genie. The brick roof of the pagoda is richly decorated with an array of wonderfully crafted ceramic ornaments: giant birds, huge bunches of flowers, figurines intertwined in capricious arabesques, and sacred lotus flowers emitting holy rays.

As we enter the left wing, closely followed by a hungry pack of local dogs, we venture through a small hidden door – this is the everyday entrance of the temple, because the great door of the front hall is only opened on festival days.

The interior is divided into several parts, each supported by many pillars of black wood on granite bases: an area adjoining the front hall is reserved for the faithful.

The middle hall comprises an open courtyard which serves to illuminate the main sanctuary. It contains a single shrine of enormous proportions, covered with embroidered silk and gold banners and surrounded by bronze-tipped wooden weapons.

The interior of a temple in Chợ Lớn

At each corner of the main (rear) hall are two bulging idols, grimacing bodyguards of colossal size, one with a black face and lance in hand, the other with his hands buried deep in his wide sleeves. Both sport moustaches and long beards, and they face each other with serious expressions. Placed on the central shrine is a statue of the famous Kuang-Ti [Quan Công or Guānyǔ]. To his right is a statue of his son Kouang-Ping [Quan Bình or Guānpíng], and to his left, a statue of his faithful squire [Châu Xương or Zhōu Cāng], resembling the ridiculous Sancho-Panza in the story of Don Quixote.

The second temple we will visit is the Kwan-chin-Hway-quan, which was built to worship the goddess Koang-Yin or A-Pho, the creative power and patron saint of sailors.

To get there, we must cross a paved courtyard of granite slabs which were brought from Canton. The entrance is guarded by two granite sphinxes, each rolling a ball between its teeth. Along the walls, we see ceramic flower garlands of a very high quality; this is unusual, because in the past, the Chinese have rightly been criticised for their rather rough work in this genre. Above these are glazed ceramic panels featuring a variety of characters. The ridges of the tiled roof are decorated with snakes and fantastic birds.

The Tuệ Thành (Guǎngzhōu) Assembly Hall, popularly known as Bà (Lady) or Thiên Hậu Pagoda

The doors are intricately carved; inside, on both sides, sit small shrines featuring bearded deities. Along the side galleries, black marble slabs covered with Chinese inscriptions are embedded vertically in the wall. Above them on both sides, a series of paintings depict mandarins sitting in judgement, ladies of the court, and scenes of equestrian combat involving spears, axes and bows and arrows.

The square open courtyard in front of the main hall is reserved for detonating firecrackers. Worshippers also set light to gold and silver votive papers, which are thrown into a large and ornate cast iron urn located in front of the shrine. The main sanctuary is separated from this space by a screen made from fine hardwood, and the pillars on either side carry twin sentences in gold characters. Here there are also wooden chairs, a wooden settee and several small wooden sideboards with marble tops.

The main hall of the temple features a canopy supported by beautifully carved pillars; beneath it, the shrines comprise vast carved and gilded wooden niches where the Chinese deities are enthroned. The main shrine is occupied by the goddess, and on either side of her are two smaller subsidiary shrines occupied by bearded deities.

Ceramic roof ridge decoration on a temple in Chợ Lớn

The goddess wears a crown topped with a red square which resembles an Italian beret. She also wears earrings and around her head is a golden halo. Near her are placed two other goddesses. Two characters with a menacing demeanour stand guard on either side.

In front of the shrine we see large screens decorated with peacock feathers, rows of triangular flags, a model junk with sails, large fragrant joss sticks, and imitation flowers and lotus buds, interspersed with small sundials, mirrors and inscribed panels. On festival days, the banners of the Cantonese congregation are displayed here, along with insignia mounted on top of painted sticks and a fragrant sandalwood cylinder which is eventually burned as a sacrifice. On one side of the shrine is a drum, and on the other a beautiful Chinese bell.

Three tables are arranged in front of the shrines to receive the sacrificial offerings, which consist of whole glazed roasted pigs, fruit, cakes, poultry, seafood and tea. At the foot of the tables are mats and cushions, where worshippers prostrate themselves and make their offerings against a background of incessant noise which includes the sounds of drums, bells and firecrackers.

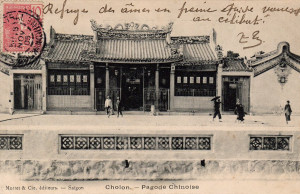

A Chinese assembly hall in Chợ Lớn in 1890

It is also in this part of the temple that worshippers have their fortunes told using the curved root of a bamboo branch split into two: the two parts are dropped on the floor and the way in which they separate and are respectively positioned is said to denote either a favourable or unfavourable prognosis. Alternatively, they can throw into the air a bunch of 49 small sticks, on each of which predictions are written; if they land in a fortuitous position which corresponds to that indicated in the books of the monks, it is a happy lot for the thrower. On festival days, the monks preside at the ceremonies, and Chinese come in full costume early in the morning to pay homage.

In the right side of the temple is a small workshop where prayer sheets are printed. The characters are first engraved in relief onto a wooden board and then the sheets are reproduced in considerable numbers. This method is not as perfect as that of the Buddhists who sent to our 1867 Exhibition a prayer machine which was capable of turning out 120 sheets each day. Nearby, they also make and sell candles, votive gold and silver papers, and stacks of ingenious imitation coins and piastre notes, which are within the reach of every budget. By burning them, the good Chinese pass these items on to their ancestors, along with clothes, utensils and everything else which is deemed necessary for the material life, all represented on coarse paper and destined to go up in smoke.

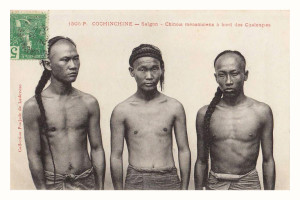

A Chinese boat crew

A compartment on one side of the main hall contains four large burners, and it’s here too that food is served on large tables during festival days. Large quantities of roast pig are sacrificed for the greater benefit of the living, who come and go within the temple precincts, talking and laughing loudly. A native orchestra mingles its discordant notes with all the rest of the noise.

On the other side is a room filled with a large table and chairs and decorated with Chinese calligraphy: it’s the boardroom of the congregation.

Besides these areas, there are still more shrines, as well as a kind of attic, which may be reached by means of a wooden staircase, but contains nothing remarkable.

We are now sufficiently educated about the interior of this temple.

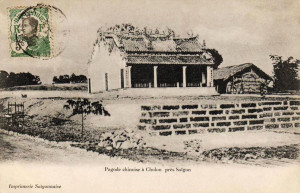

The third pagoda we will visit is the Pagode-neuve (New pagoda), which is dedicated to the Buddha. I attended its solemn inauguration, presided over by a monk who came especially from Tibet, and on whose travel huge sums had been spent.

A “Chinese pagoda” in Chợ Lớn

A deep ditch, protected by a dry stone wall, separates the Pagoda from the street. Its exterior and interior decoration is similar to the previous two. One notices, however, a unique and wonderful work comprising six enormous granite columns, around each of which the artist sculpted gigantic dragons. Two of these columns are placed at the entrance to the front hall, two in the middle hall, and two on either side of the main sanctuary.

Right opposite the pagoda on the other side of the street is a vast enclosure surrounded on three sides by high walls decorated with gigantic tigers. The side facing the street is decorated with a lattice fence, through which it is possible to see all of the goings-on inside. However, this space is usually empty, being reserved for stage performances on festival days.

This is the general appearance of the famous pagodas, of which there are nearly 30 in Cholon. But none are as rich as those which belong to the Chinese.

The three pagodas that I have just described are located in the street that leads back to Saigon, not far from the Catholic church and the convent of the French nuns.

The Plain of Tombs

As we head back down that street, we pass the magnificent residence of three Indigenous Affairs Administrators, surrounded by a beautiful garden. In front are the guards’ barracks. Here we are back on the route des Mares, alongside which, set amidst huge mango trees, are situated numerous brick factories. After that, we must bid farewell to all the movement and life, because from this point onwards the eye contemplates only the sorry weeds of the Plain of Tombs.

Since 27 December 1881, Cholon has been connected to Saigon by a steam tramway line, which has succeeded wonderfully. It appears that its trains carry no less than 2,000 to 2,500 Asians each day, for the price of just 0 Fr.30. This is an excellent result. In their colourful language, the Annamites have dubbed this tram the cheval de feu (“fire horse”).

I don’t suppose that you expect me to write an in-depth essay on Chinese drama. Apart from the fact that the language is totally unknown to me, I must say that I have very rarely attended performances at the theatres in Cau-ong-Lanh or Cholon. All I can say is that the dramas, based on either history or fantasy, usually last two or three days, and that each evening performance extends for seven or eight hours. Everything is interconnected, from the main story, entr’actes and pantomimes, to the conjuring shows in which the Chinese excel. As for the décor, it is primitive. The scene never changes: a simple sign, hanging from a string or nailed onto a board, successively indicates change of place.

A Chinese theatre troupe

Members of the audience are content with these limitations and intelligence makes up for what cannot be glimpsed by their eyes. The lighting also leaves much to be desired. The backstage candle-snuffer is not in the least embarrassed to walk half naked across the stage in order to carry out his duties, even while the hero is delivering a speech, neither do the spectators seem to care.

As for the orchestra, it sits at the back of the stage and plays almost continuously; but its frenzied cacophony is one of the cruellest punishments which can be inflicted on the newly-arrived European. In a word, attending a Chinese theatrical performance once, in passing, can offer the charm of the unexpected; but attending a second time – which no-one is forced to do – is, in my view at least, a tedious chore for which there is neither excuse nor explanation.

The Chinese also play comedy and vaudeville. But I would not commit any of my French lady friends to risk viewing such performances. These representations are all too often of a revolting immorality. The Asian is never afraid to present on stage acts which, by their very nature, should be confined behind closed doors. On one occasion, the government intervened to defend the actors of the Cau-Ong-Lanh Theatre from attack by neighbouring Europeans who deemed their foul improvisations to be both offensive and dangerous.

An outdoor performance of Chinese theatre

In Cholon and other remote centres, the administration has more scruples. For my part, I wanted to attend one of these hideous representations, in order that I could understand the extent of their licentiousness. I must admit that eventually I had to retire in disgust. The Chinese are a people of little prudishness, and the Chinese audience members revel in such spectacles, which they supplement with a barrage of their own shameless jokes, made in loud voices at all of the most risqué points of the performance. Note that the Chinese never applaud with their hands. Their laughter alone, which they produce without restraint, indicates their satisfaction.

The first time I attended a performance at Cau-Ong-Lanh was at the opening of the theatre season, in June. Two of my colleagues and a Saigon lawyer accompanied me. The impresario had arranged everything splendidly. As the troupe knew in advance that three French judges would “honour” the festival by their presence, a carefully-stocked buffet was installed in the gallery which had been reserved for Europeans. Nothing was lacking, not even the champagne, that wine so dear to the wealthy Chinese! Needless to say, we could enjoy all this without spending a penny, for this gracious kindness was paid for in its entirety by the banker Mr Banh-Ap, farmer of opium in Cholon and sponsor of the theatre.

The entrance to the former arroyo Cau-Ong-Lanh

We were escorted by one of the native interpreters of the legal department; but the manager of the troupe, fluent in French, wanted to explain the scenario and the events of the drama himself. Besides, a little surprise had been arranged. As the curtain rose, the principal actor, advancing alone to the front of the stage, addressed us with a pompous harangue, partly improvised, we were told. It seems that this preliminary declamation was customary in the presence of Frenchmen of importance who attended the opening performance of the season.

The translation that was made to us was remarkable, though perhaps a little too hyperbolic. Having arrived at half past eight, we did not retire until well after midnight.

The area surrounding Cau-Ong-Lanh Theatre is hard to describe. The building is accessed via a long wooden corridor, decorated with a multitude of fantastic banners and colourful lanterns. During festival times, firecrackers are detonated frequently, their noise echoing through the arroyo. No-one burns as much gunpowder as the Chinese, who distinguish their every festivity in this way. We have even had to ban this practice in some of the more crowded locations of the city, in order to avoid accidents.

The old Cầu Ông Lãnh Market

The theatre emits a bright red glow from many sections of its roof, which extends far into the night. This glow and the sound of the audience and the firecrackers have often been mistaken as signs of a major fire.

The Cau-Ong-Lanh Theatre building is constructed entirely of wood around a huge rattan frame. All this is of proven strength. As for the numerous corridors which radiate from it, these are all packed with little businesses from which entrepreneurs derive great profit.

However, those of high moral standard will find little of satisfaction here, because gambling houses and brothels are in the majority.

Indeed, these constitute one of the necessities of Chinese life. They are not the most sumptuous of places. On both sides of a low and narrow corridor next to the theatre are a series of small rooms containing furniture as minimal as the wardrobe of the courtesans they house.

But the women spend little time here. In the evening, a crowd flocks to the doorstep of this establishment and the highest bidders are free to conduct the women whose charms have seduced them back to their own homes.

The streets behind the Hôtel Wang-Taï or Hôtel Cosmopolitan were a red light district in the early 1880s.

Europeans do not disdain from attending these kinds of establishments in Saigon, almost all of which are grouped immediately behind the Hôtel Wang-Taï in the rue des Fleurs.

But the installations.of Cau-Ong-Lanh offer them serious competition.

Unfortunately, French residents are too easily led to imitate the moral turpitude of the Chinese, which is definitely not the way to raise our colony.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.