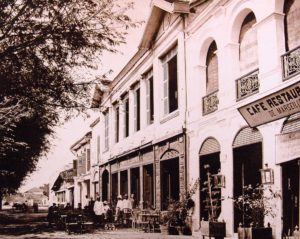

Chinese shops on the rue Catinat

Life in Saigon changes little from day to day. Indeed, it will be much the same tomorrow as it was today and yesterday.

The days when the Messageries Maritimes courrier vessel arrives from France are without doubt the most interesting days for everyone in this town.

The arrival of the courrier vessel within sight of Saigon (which, because of the many meanderings of the river takes place long before its actual arrival) is announced by the hoisting of a black ball on the Signal Mast, and accompanied by a shot from the cannon of the good ship Duperré. Its docking at the port in front of the Messageries is signalled by a second shot. The courrier vessel must wait for the tide in Cap Saint-Jacques before sailing up the Saigon River, so in order to save some time, a small steam ship is usually dispatched to Saigon ahead of it, carrying the most urgent mail from France. It is expensive to take advantage of this service, but some find it useful.

Saigon harbour in the late 19th century

The courrier vessel stays for 24 hours in Saigon before leaving for Hong Kong.

Soon after the arrival of the courrier, colonial residents go to the post office to collect their letters and parcels; this is a most enjoyable time for everyone,

A few hours after the arrival of the courrier from France, a second courrier vessel coming from Japan and China also arrives in Saigon. It too remains here for just 24 hours, then leaves for Europe carrying letters and packages from Saigon. At this time, traders are very busy; they have just 24 hours to process a voluminous quantity of correspondence, take important decisions and draft replies. Only after both steamers have left does calm return to Saigon.

The greatest public distraction in Saigon is “la musique,” held at 8.30 every Friday evening and often thwarted by rain, a problem which affects almost all concerts held on fixed days and at fixed hours. A number of military officers, sailors and colonial officials pace up and down in front of the musicians; ladies are very rarely present.

There is now also an important official distraction in Saigon, a bimonthly soirée hosted by the Governor, who issues a circular to a selected few every 15 days, announcing that he will open his salons to them. So let it be known!

The barn which serves as a reception room for this event is equipped at each end with two small raised platforms. One serves as the ladies salon, while the other accommodates the musicians, and dancing takes place in the space between them. The evening often begins with a theatrical performance presented by local amateurs, for which the musicians’ platform serves as a stage. After the performance, the seats are removed from the dance area, the ladies go and sit on their platform, and the dance commences.

French military officers on parade in Saigon

This is when the vigorous lieutenant-commander or the energetic marine clerk get to work. The ladies… Ah! The ladies! But shh, let’s talk softly. All colours of skin are represented here, from the pale hues of Europeans exhausted by the climate to the darker shades of the so-called “créoles.” Later, the Governor gives a little speech. He has been hosting a dinner in a room adjoining the barn, with Mrs X on his right side, Ms Y to his left, and in front of him the General of our troops. After this meal, while the gaiety fuelled by champagne wine is at its height, the Governor rises, and, with a voice moved by the circumstances, delivers his small address. He offers a toast to the ladies of Saigon who have the grace of the Virgin Mary (and probably all the qualities, too).

At the end of the evening, everyone withdraws, dripping with sweat and emotion. Such are the official pleasures of colonial Saigon.

After dinner, the men take a little promenade, spending the rest of their evening at the Cercle des officiers. As I have said, life on one day in Saigon is much the same as it was the day before and will be the day after.

The promenade on horseback or by horse-drawn carriage from 5.30 to 6.00 in the evening is a popular distraction, but it’s always the same. The same large man carrying a baton and putting on the airs of a Marshal of France; the same aide de camp, as thin as a cuckoo, shrivelled with resentment after being repeatedly overlooked for promotion to captain of frigate; the same young Bourbonnien, swerving from left to right on his tiny nag which he launches at a gallop until it’s ready to drop….. The normal route of the promenade by carriage is the road which leads to the Chinese town of Cholon, 5 kilometres from Saigon; half way along is an army barracks known as les Mares.

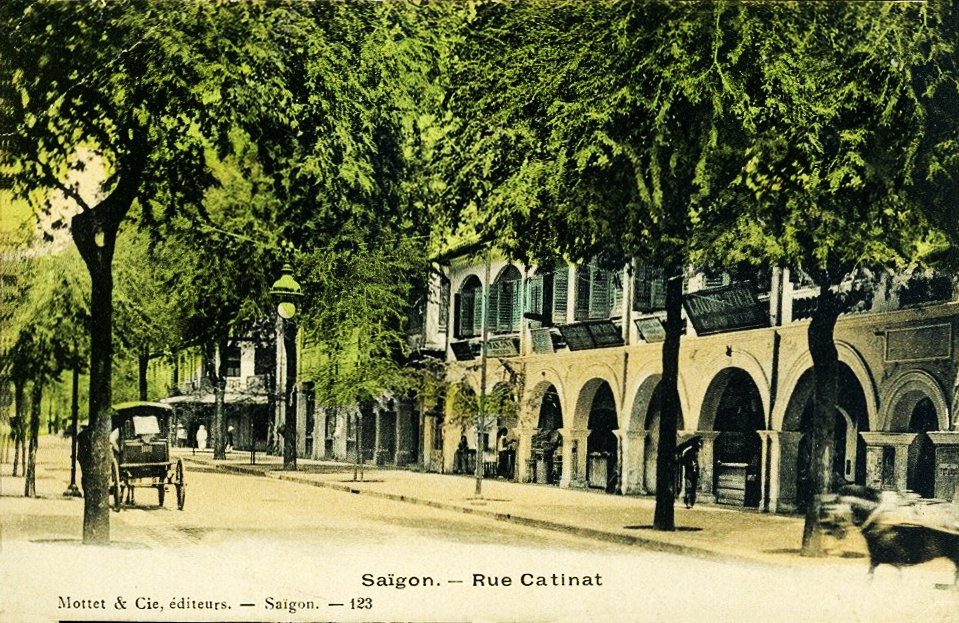

The rue Catinat in 1890

Saigon at night

For an evening walk through the city, start by descending the rue Catinat, principal thoroughfare of Saigon, to the quayside. Then, passing the Maison Wang-Taï, take the rue Rigault de Genouilly as far as the rue de l’Eglise, take the rue d’Adran to the market and finally return to rue de l’Eglise along rue Chaigneau. This will permit you to visit the entire Chinese district of the city.

As you descend the rue Catinat, you’ll pass Chinese shops and a few French houses to your left and right. This is the main street of cobblers, tailors, purveyors of canned food, etc. The Chinese businessmen Apan and Atho, well known in Saigon, do business here.

Within a single shop, one may find tailors and cobblers working together. All of the shops are located on the same level as the street and you can enter at will, since everything opens directly onto the street.

When we walked down this street, we saw inside one shop five or six coarse lamps with paper lampshades; these lamps were placed on the ground or on low tables, and around them were gathered eight to ten Chinese, shirtless, legs crossed, each working on one garment. The light projected onto their bare shoulders shone in a strange way. Behind them on the wall was a large image of the Buddha on yellow paper, with red and blue decoration. There was also a mirror with facets which sparkled in the light. Beyond the shop area we saw a back room. It was a resting place which we could not penetrate – the shop dog, seeing me stop and look, barked. He clearly doesn’t like the French!

Chinese shops on the rue Catinat

In this part of the street there are five or six stores, located side by side. If you have seen one you have seen them all.

Leaving the shop, I passed a lantern which illuminated an itinerant food vendor carrying over his shoulder two heavy baskets supported at opposite ends of a long pole. He sounded his usual cry, one which is well known to his customers. One of the Chinese inside the store called to him: the food vendor stopped, lowered his baskets to the floor, removed the carrier rod from his shoulder, breathed a little, then started to prepare the pittance requested, the ingredients of which he took from five or six different pots – two peppers here, three species of beans there…. He blew on his little fire to prevent his dish from getting cold. In such situations, the customer, standing or sitting according to the time he can devote to feeding, eats somberly and pays little. The food vendor left, and his cry was soon heard a little further along the road. Sometimes, mischievous Annamite boys working in the service of French colons will deliberately call two of these food vendors at the same time, forcing the poor devils to compete for their customers.

Suddenly, close by, we heard in the dark the sound of a silvery voice, sweet, plaintive, melancholic. It was the cry of a little boy aged just 7 or 8 years, who ran through the streets carrying on his head a basket containing small pieces of sugar cane. Just 20 centimetres long, they are sold cheaply. They are then peeled, or given two or three knife incisions to liberate the sweet juice; all the Oriental peoples – Annamites, Chinese, Malays and Indians – find this juice delicious.

On the left side of the street, you will see the shop of the Chinese merchant Apan, sparkling with tin boxes of canned food and glass bottles of various liquids.

Cafes on the Saigon River quayside in the late 19th century

Further along in the shadows, standing on the corner of the street, who is this mysterious character wearing a blue garment and a cap of cylindrical blue cloth, carrying a sword at his side? It’s a night watchman, who each night is supposed to prevent the store of his boss from being robbed. Thieves are bold in Saigon, as I can vouch from personal experience.

Opposite, you’ll see the famous Salle des ventes (Auction room). At this time of night it’s closed, of course.

Further down are the garage and stables of the Malabars, who rent out horse-drawn carriages. Several dark shadowy forms, wearing little by way of clothing, rub down and harness sad horses to sad carriages. Their companions, bodies glistening with coconut oil, bask in a sweet sleep awaiting customers.

Near the bottom of the street is the shop of the Chinese merchant Atho, a branch of the shop belonging to Apan. Arriving finally at the quayside, you’ll see a few French cafes, whose customers drift in and out loudly.

From the quayside, we forked right onto the rue Rigault de Genouilly, but then left it almost immediately, turning into a very short, tiny street located immediately behind the Maison Wang-Taï. This street is made up of two parts, each at a right angle to the other; to the right and left are the busiest gambling houses in Saigon, along with several other more seedy establishments. In front of the shop openings, as with the Chinese shops, hang large spherical or cylindrical lanterns made from coloured paper of various types, with inscriptions in huge Chinese characters. Considerable animation reigns in this street, which is home to at least four or five gambling dens.

The players are so engrossed that you can stand and watch them without fear of being disturbed. As I said, there is no door to these gambling establishments. The walls of the houses facing the street do not exist at ground floor level; you may go straight into a small room where you will find three or four Chinese sitting around a mat on which the game is played. The game can continue for several hours; sweat trickles down every face and a croupier sings a monotonous chant, a chant of death or triumph, until a winner emerges.

An itinerant food vendor in Saigon

When important players arrive, in order to show them respect, the mat is spread on a table at about waist height rather than on the ground, as is the practice in more vulgar gambling establishments.

Here one often sees French soldiers or sailors playing and fraternising with the children of the Middle Kingdom – the soldier with his blue jacket and white salaco, the naval deckhand out on a binge… Sometimes you’ll even see a boy gambling with his master’s money – if he loses, he’ll run. If he wins, he’ll also run! The number of gambling dens in Saigon is frightening, there are now around 40, not to mention those of Cau-Ong-Lanh and Cholon.

Almost all day long, and especially at night, you’ll hear the monotonous song of the Chinese croupier, or the metallic sound of his copper chips which, in between games, he places in a large canvas bag, holding the ends in each hand and shaking them strongly in order to attract customers. Everyone plays!

But let’s leave this small alley, where we have stayed too long already. As we leave, we can see through wooden window bars of adjacent houses groups of women dressed in the Chinese style, like ferocious beasts behind their gates, making all the propositions they believe customers will find the most engaging.

Soon you will arrive in a muddy square steeped in the stench of the market. This is the rue d’Adran, where you’ll find many more gambling dens, and also some fruit and sugar cane sellers, who set up their mobile stalls in the street. They sell their products to the Chinese and to wheelwrights, carriage repairers and joiners who live in this area.

The rue Rigault de Genouilly was on the west side of the Grand Canal (now Nguyễn Huệ boulevard)

We continued to the rue de l’Église, having visited almost all the Chinese quarter. At 9.00 we heard the distant melancholic sounds of a bell marking the extinguishing of the fires at the Camp des lettrés and the tam tam of the Inspection de Saïgon.

We stayed in Saigon for several weeks, meeting the inhabitants of this city, both European and Asian. We paid our price to the climate of the country by spending a few days afflicted with the most common ailment. In our carriage rides, we went to the Chinese town of Cholon. We visited the pagodas, which are quite remarkable, especially the exteriors, which feature monstrous dragons in blue, green and red, with flaming tongues, terrible eyes bursting from their sockets, and long tails with bristly spines down their backs.

Cholon is a very populous city. It is in the hands of the Chinese, who make a great trade from the rice of Cochinchina. It is also the residence of our Inspector of Indigenous Affairs.

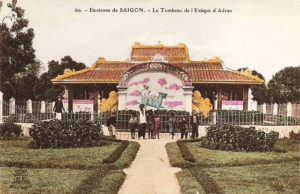

We also went across to the other side of Saigon, taking the route de Govap and visiting the tomb of the Bishop of Adran. Located around 3 or 4 kilometres from the town, it sits in a grove of trees on the edge of a vast plain of rice fields which stretches out from the plain of tombs. Entering the enclosure, we found ourselves in front of a vertically-placed flat granite stone, on which was carved an inscription in local characters, reproducing the titles of the Bishop of Adran given by the sovereign and his people for services the Bishop had rendered to the country. Behind this stone was one of the entrances to the tomb itself, a kind of pagoda built through the munificence of the king.

The Chinese caretaker, attentive to visitors, opened the doors of the tomb. Inside, we saw a rectangular masonry structure around 1 metre in height, beneath which lay the remains of the Bishop of Adran. Behind the tomb was a small altar where one can say mass.

The tomb of the Bishop of Adran

I need not reiterate here the services rendered by the Bishop of Adran to the rulers of Cochinchina nearly a century ago. He was one of these brave Frenchmen who, at the end of the last century, knew how to make our name loved throughout Cochinchina. In particular, he was one of those energetic missionaries who have carried, and continue to carry, the flag of the Catholic faith high and firm into the most far-flung regions. It was not without emotion that we visited the tomb of the Bishop of Adran. At the entrance to the grove where the tomb is located, we also saw the grave of one of our missionaries, who died a few years ago in the dungeons of the last ruler of Annam. An inscription on another vertically-placed flat granite stone gives the name of the martyr whose remains rest in this place.

I remember visiting this tomb as the last rays of the setting sun made the characters of the inscription sparkle. Nature was peaceful, a few buffalo grazed in front of me, under the watchful eye of a small Annamite boy, happy to tread this ground of rice paddies on which stood two or three miserable cai-nhas. We returned at night along the Govap road, bringing us a few minutes later back into Saigon.

During our stay we also crossed the arroyo-Chinois and visited the Fort du sud, passing more cai-nhas located at the edge of the Saigon river, downstream from the town.

Then we retraced our steps back across the arroyo-Chinois and took the street which runs through Cau-Ong-Lanh, following another row of Annamite cai-nhas built at the edge of the water. This area has a small Catholic church that I was not able to visit, its doors being constantly closed. The rectory is next door, and it struck me that perhaps the priest is not often in his parish. There are two brickyards along the Arroyo, they both belong to Wang-Taï. Finally, we returned to Saigon and crossed the river, where another Catholic village and the workshops of a boat builder may be visited.

While these little excursions give us only a superficial idea of Cochinchina, they also encourage us to make a real excursion into the Interior of the country.

Chinese shops on the rue Catinat

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now and Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.