The new Saigon Dry Dock, inaugurated on 3 January 1888

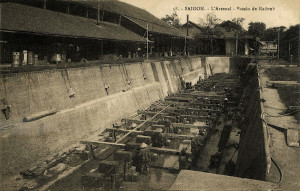

Saigon’s new Dry Dock was inaugurated on 3 January 1888 with exceptional solemnity, and that is understandable, for this work, remarkable from a technical point of view, is of considerable importance for the future of our colony. It is clear that the facility it will give to large ships, not only to refuel, but also to undergo repairs in our large Far Eastern port, will help to establish Saigon as a commercial centre of the first order.

It must be recognised that this is a work on a grand scale, because the new Dry Dock was designed for ships of the largest tonnage. Indeed, while the dry dock in Toulon measures just 114m in length, that of Saigon is no less than 166m.

The RMS Etruria of the British & North American Royal Mail Packet Company (Cunard Line)

It may therefore receive the largest liner known, the Cunard Company’s Etruria, which is 158m long, as well as the four great liners just built for the Compagnie générale transatlantique, each of which are 155m in length.

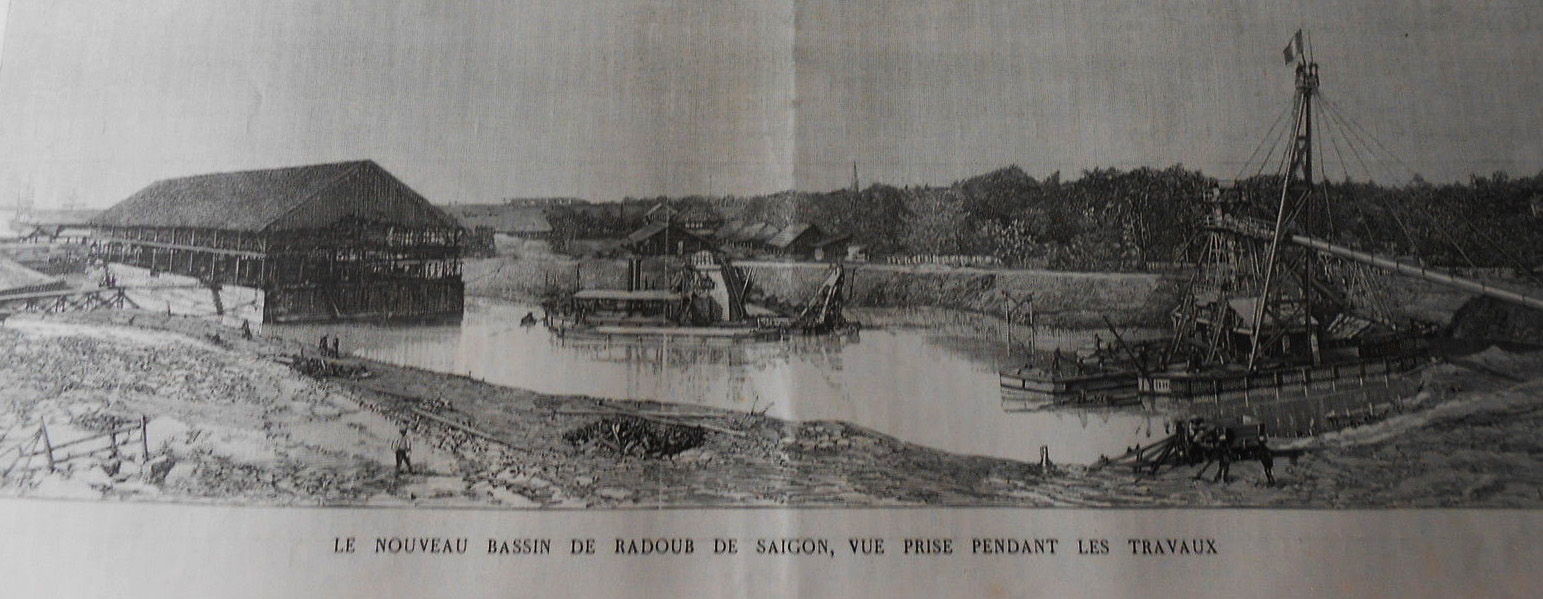

This gigantic work is therefore one of national significance which represents the highest honour for M. Hersent, the entrepreneur who was charged with this difficult task, already made famous by the work he has done in Suez. Beside him, we must also mention M. Baruzzi, the engineer who led the work on site. Two plates of black marble, placed to the right and left of the main doors, bear the names of all those who contributed to this great project.

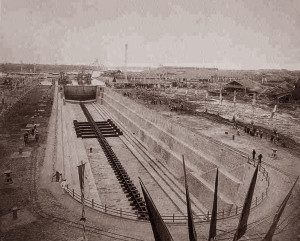

The execution of this immense work was conducted with extraordinary rapidity, taking just three and a half years, even though the specifications permitted the contractor four years to complete the task. Where major public works are concerned, this is a very rare occurence which merits particular attention.

Also of note is the fact that the work was accomplished by a team of overwhelmingly Annamite (Vietnamese) workers. They were led by a staff of 35 Europeans, including engineers, managers and foremen.

The Dry Dock under construction in 1887

One cannot over-praise the opening of this splendid new Dry Dock, the inception of which cannot fail to exert considerable influence on the development of our commerce. A few figures will not be out of place here.

In 1806, the movement of trade was as follows: Imports amounted to 39,332,375 francs, and exports to 39,390,000 francs. By 1870, imports had increased to 68,037,406 francs, and exports to 62,099,318 francs. The figures for 1879 applied only to movement within the Saigon port by European vessels, so in order to know the total commercial movement of Cochinchina, we must add the movement of Chinese junks, equivalent to 1,500,000 francs, and of Annamite boats, amounting to at least another 15,000,000 francs. So in 1879, the traffic of Saigon port generated over 146 million francs. Since 1879, there has been encouraging progress.

Unfortunately, what Cochinchina lacks most are colons. French traders still occupy a secondary place in Saigon, and much more trade is in foreign hands than in ours. Traffic between Saigon and Hong Kong, for example, is carried out much more by German and English ships than by French ships.

The Dry Dock in the early 20th century

“Cochinchina,” wrote M Leroy-Beaulieu in his book on colonisation, “may one day provide a vast market for our products, in exchange for which it will also provide us with abundant supplies of rice, tortoise shells, elephant tusks, silks, wood, salted fish, skins and oils. The capital of our colonial possessions, Saigon, though situated 60 nautical miles from the sea, is accessible to ships of the highest tonnage … It forms one of the main stops of our Messageries maritimes. It is to be hoped that we will extend to this franchise the same policies which brought about the grandeur of Singapore.”

There is also another very good reason to foster the development of Saigon: the piercing of the Isthmus of Tenasserim, which closes the peninsula of Malacca.

P. M.

The Dry Dock under construction in 1886

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.