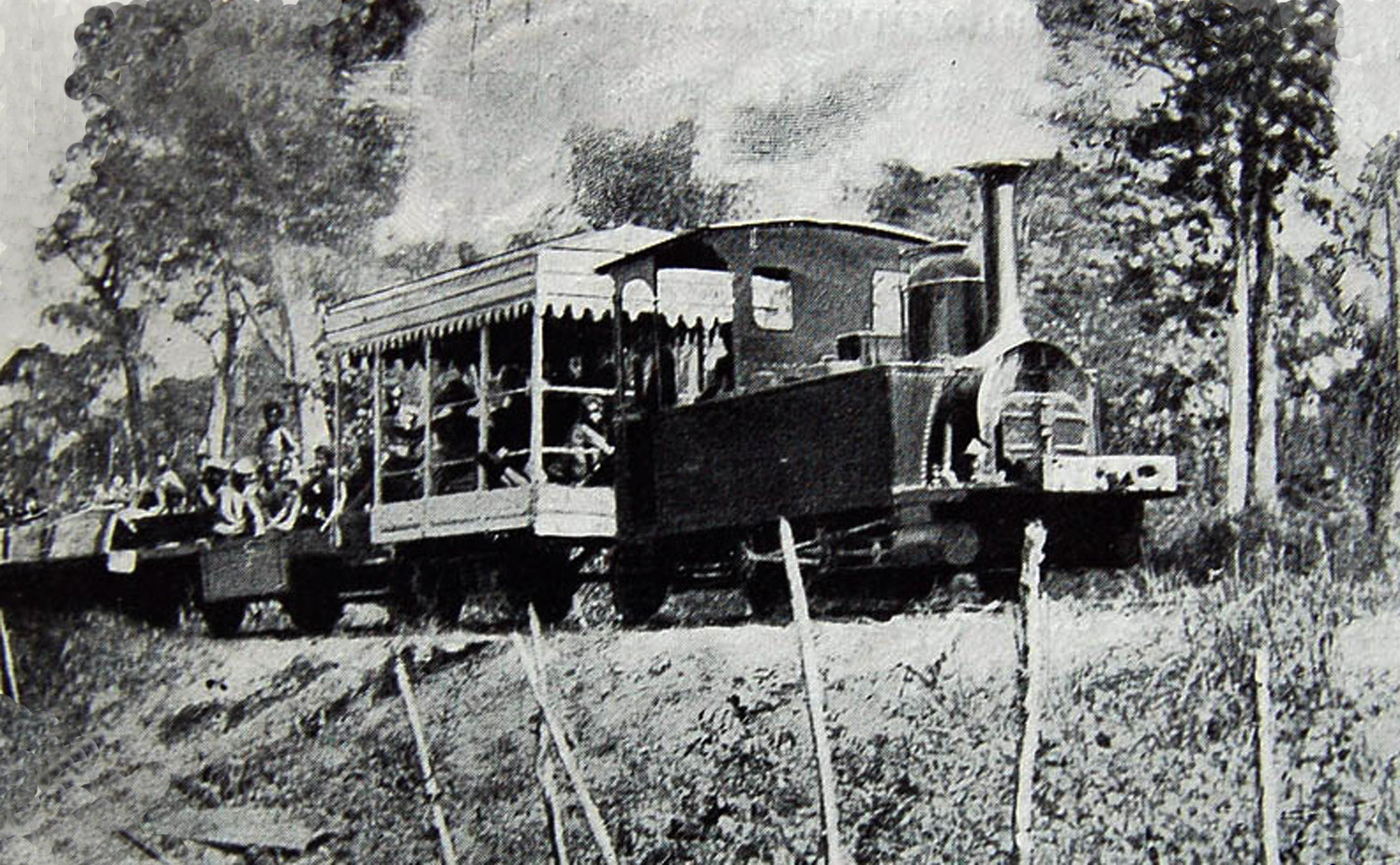

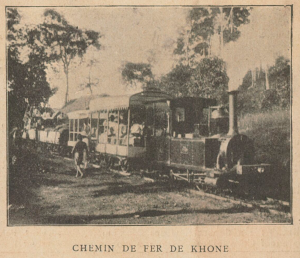

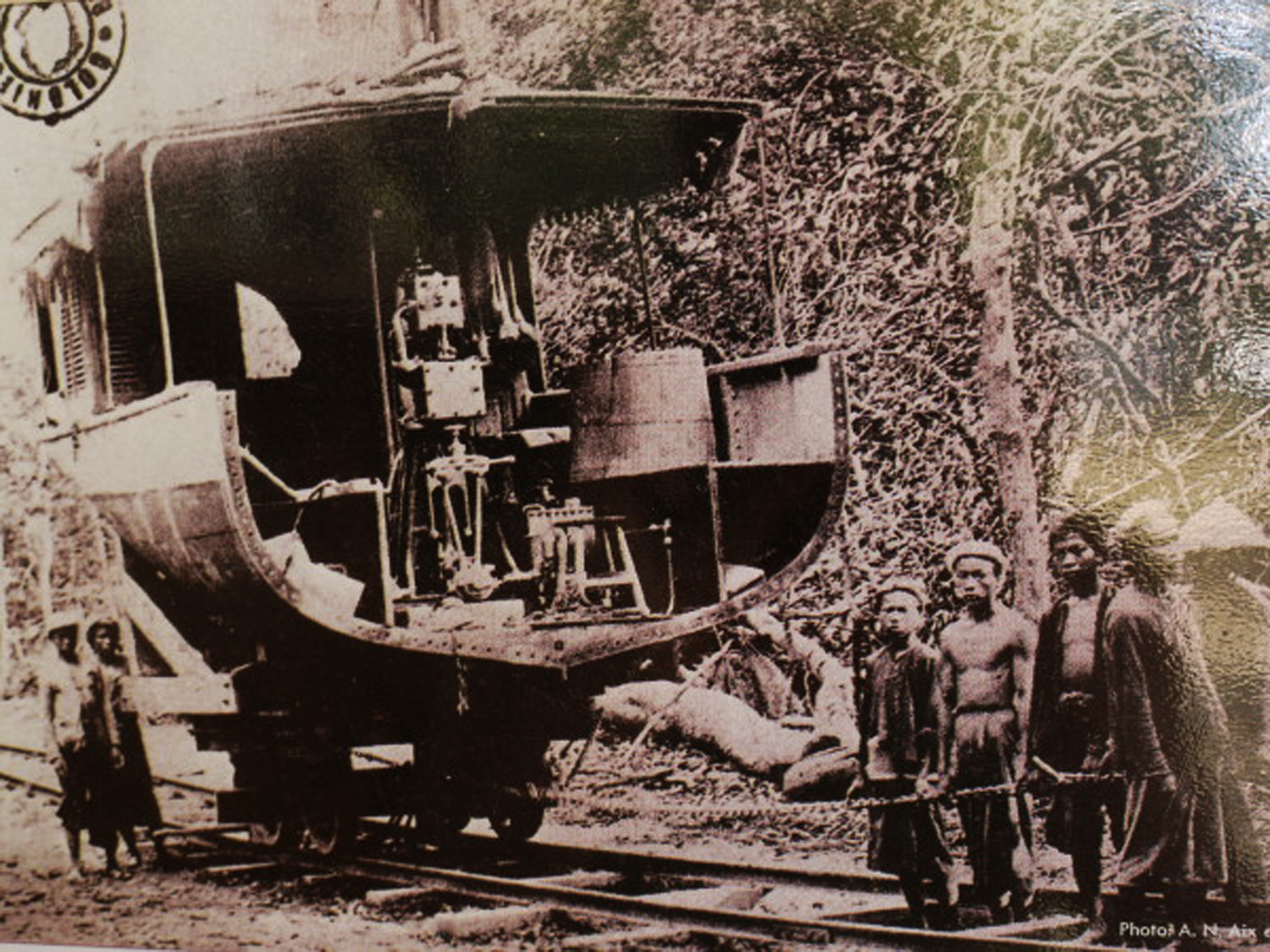

Schneider 0-4-0T (020T) 1m gauge steam locomotive supplied to the Khône railway by Société des Forges et Ateliers du Creusot in July 1897, Compagnie des Messageries Fluviales de Cochinchine

The only working railway in Laos before 2009, the Khône Island line in Champassak province was built between 1893 and 1924 as part of the effort to assert a French presence in the Upper Mekong region and encourage the export of Lao goods through Saigon rather than Bangkok..

A colonial-era postcard of the Khône Falls

As they advanced their interests along the Mekong River, the French quickly found an insurmountable obstacle to navigation in the 15m high Khône falls, located some 500km from the river mouth. Since the irregularity of its water flow mitigated against the construction of a lock system, they decided instead to build a portage railway to connect the two sections of river..

When it first opened in 1893, the line ran 5.5km across the island of Don Khône from Khône-Sud to Khône-Nord. Its primary function was to transport gunboats and steamships, which were dismantled on one side of the falls and reassembled on the other, thereby linking Saigon and Phnom Penh with Pakse, Vientiane and Luang Prabang.

Built from the outset in 1m gauge, the line was initially powered not by locomotives, but by requisitioned labourers.

The riverboat “Trentinian” being transshipped across Don-Khône island by rail in 1896

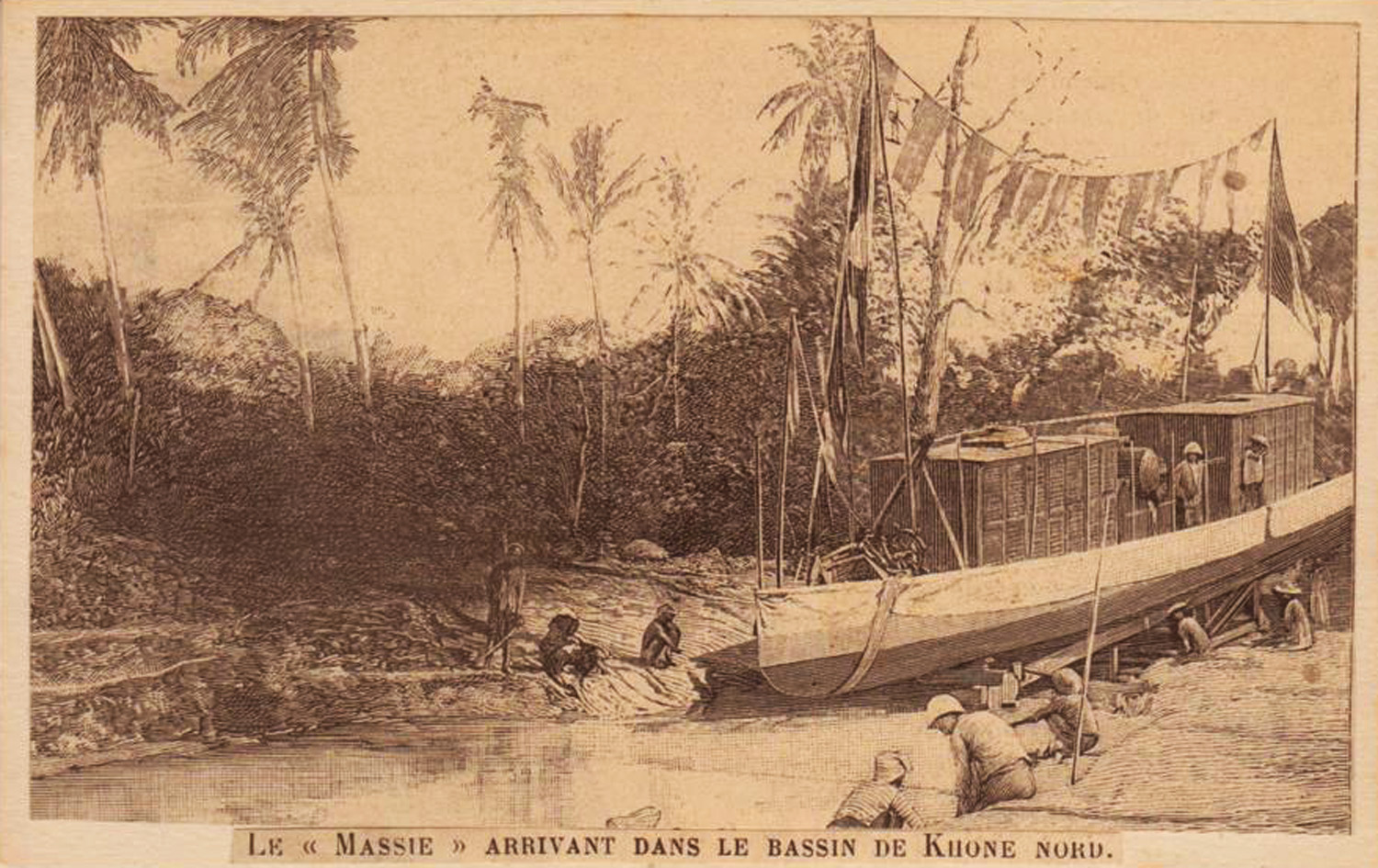

It was used to transship the gunboats Massie and La Grandière and the steamship Ham-Luong in 1893, the government launch Haïphong in 1894 and the steamboats Garcerie, Trentinian and Colombert in 1896. However, the line was usable only during the rainy season, since the docking of steamships at Khône-Sud and Khône-Nord was not possible at other times of the year due to low water levels.

In 1897, the Khône railway became part of the weekly subsidised Saigon to Vientiane postal boat service run by the Compagnie des Messageries Fluviales de Cochinchine (CMFC). In that year, human power was replaced by a 1m gauge Schneider 0-4-0T (020T) locomotive from the Société des Forges et Ateliers du Creusot. At this time, the line also received a modest range of wagons and flat trucks. Thereafter, while still capable of transshipping the occasional river boat, the Khône railway became first and foremost a means of transporting passengers and freight between Khône-Sud and Khône-Nord.

The 13-arch masonry viaduct (163m) built to carry the 1.8km Khône-Nord to Don-Det extension across an arm of the Mekong River, completed in December 1923, Musée du quai Branly

In 1914, plans were drawn up to extend the line across a 163m, 13-arch masonry viaduct to Don-Det, to build a larger quay in Don-Det and to construct a 12km navigable channel between Don-Det and Khinak (previously the terminus of canoe navigation at low water) for use in the dry season. However, this project was delayed by war and would not be completed until 1924.

Henri Cucherousset, editor of the newspaper l’Eveil Économique, travelled the line in 1924 en route from Hà Nội to Phnom Penh. In an article published in 1927, he provides us with an amusing account of what it was like to travel on the “Khône Nord-Khône Sud Express.”

The locomotive, which he describes as “never having been fussily maintained, that is to say, just enough to keep the wheels turning,” hauled “a deluxe car comprising a covered flat wagon with a garden bench in the middle, which has never seen paint” and “one or two flat wagons for freight.….This lovely ensemble advanced with a deafening clanking at 8km per hour.”

Schneider 0-4-0T (020T) 1m gauge steam locomotive supplied to the Khône railway by Société des Forges et Ateliers du Creusot in July 1897, Compagnie des Messageries Fluviales de Cochinchine

In 1927, the subsidised Saigon to Vientiane postal boat concession was taken over by a subsidiary of CMFC known as the Compagnie Saïgonnaise de Navigation et de Transport (CSNT). The Government General of Indochina placed an order with Compagnie française de matériel de chemin de fer (CFMCF) to supply the company with new rolling stock for the Khône railway line, including 1 x passenger carriage, 2 x covered freight wagons and 3 x flat wagons. Later that same year, several tanker wagons were also ordered.

Surprisingly, no attempt appears to have been made to replace the original Schneider locomotive, which in 1928 was declared “too weak to tow the new equipment purchased for the administration in 1927.” Consequently, train loads had to be restricted to 31 tonnes, even though during high water season demand could reach 280-300 tonnes per 10-hour day. In 1928, CSNT was offered one of the Saigon-Mỹ Tho line’s old 15-tonne Hanomag 0-6-0T locomotives second-hand, but it appears that this offer was declined – in 1933, the Schneider 0-4-0T was reported to be still the only means of traction on the island.

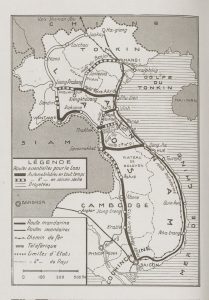

At this time, the attention of the Indochina government was increasingly focused on the development of a servicable road network. A road from the Cambodian frontier to Savannakhet built in 1925-1928 made it possible to by-pass the Khône falls altogether; in the early 1930s, that road was upgraded to become part of Route Coloniale No 13 from Saigon to Luang Prabang and by 1937 it was possible to drive all the way from Saigon to Thakhek. During the same period, both Route Coloniale No 9 from Đông Hà to Savannakhet and Route Colonial No 8 from Vinh to Thakhek were also upgraded from dirt tracks into paved roads.

The development of a paved road network into Laos in the 1930s made it possible to by-pass the Khône Falls – Routes essentielles pour le Laos, Le Monde colonial illustré, 1 janvier 1938, p 72

With road transportation now a real alternative to a difficult passage through the lower reaches of the Mekong River, a plethora of private road haulage companies sprang up to compete with CSNT. Already impacted by the economic downturn, traffic on the Saigon to Vientiane service declined to just 3,424 tonnes of freight and 2,970 passengers in 1933.

In 1937, believing that Route Coloniale No 13 rendered the subsidised postal steam boat service obsolete, Governor General René Robin (23 July 1934-9 September 1936) terminated CSNT’s contract and opened its various services to competitive tender. Établissements Bainier of Saigon was awarded the contract for the now three-times weekly return postal and passenger bus service between Saigon and Pakse (612km), with a contract period from 1 September 1937 until 30 June 1941. This service by-passed the Khône Falls by taking Route Coloniale No 13, which was known by this time as the “Route René Robin.”

The subsequent history of the Khône railway is shrouded in mystery. Despite no longer being used by the postal service concessionnaire, it was reported in 1937 that the line continued to be operated by the administration “in correspondence with river transport services.” However, with competition from a paved road, its future must have been uncertain.

Remains of a 0.75m gauge Orenstein & Koppel 0-4-0T (020T) locomotive at Khône island railway exhibition centre in Ban Khon village, photographer unknown

Following the Japanese occupation of Indochina, a treaty of 1941 redefined the Franco-Siamese boundary, awarding Khône island to Thailand, and the railway line fell into disuse. However, in April 1945, the Japanese military conducted a survey of the Khône railway and decided to restore the line to working order. The Japanese Embassy in Bangkok formally requested the Thai government’s permission in early May 1945 and began shipping supplies, rails and sleepers to the island later that month. They rebuilt the line using 0.75m gauge track with steel sleepers and on 13 August 1945, the Governor of Champassak reported to the Thai Interior Ministry that four kilometres of track had already been laid. However, the Japanese surrendered two days later, ending the war. The Franco-Thai settlement treaty of 17 November 1946 returned to France all the territories taken during the Franco-Thai war and Don-Khône once more became Indochinese territory. However, no further attempt would be made to reinstate the Khône railway.

In recent decades, the old track bed of this curious line has become a popular tourist attraction for visitors to southern Laos. In Hang Khon (the former Khône-Sud), the rusting hulk of a 0.75m gauge Orenstein & Koppel locomotive has survived and now forms part of a small outdoor exhibition on the history of the line. The remains of a 0.75m gauge Decauville locomotive may also be seen further north, near the Don-Det viaduct. Since the line was originally of 1m gauge, it is very likely that both of these locomotives were shipped here in 1945, during the abortive Japanese attempt to rebuild the line.

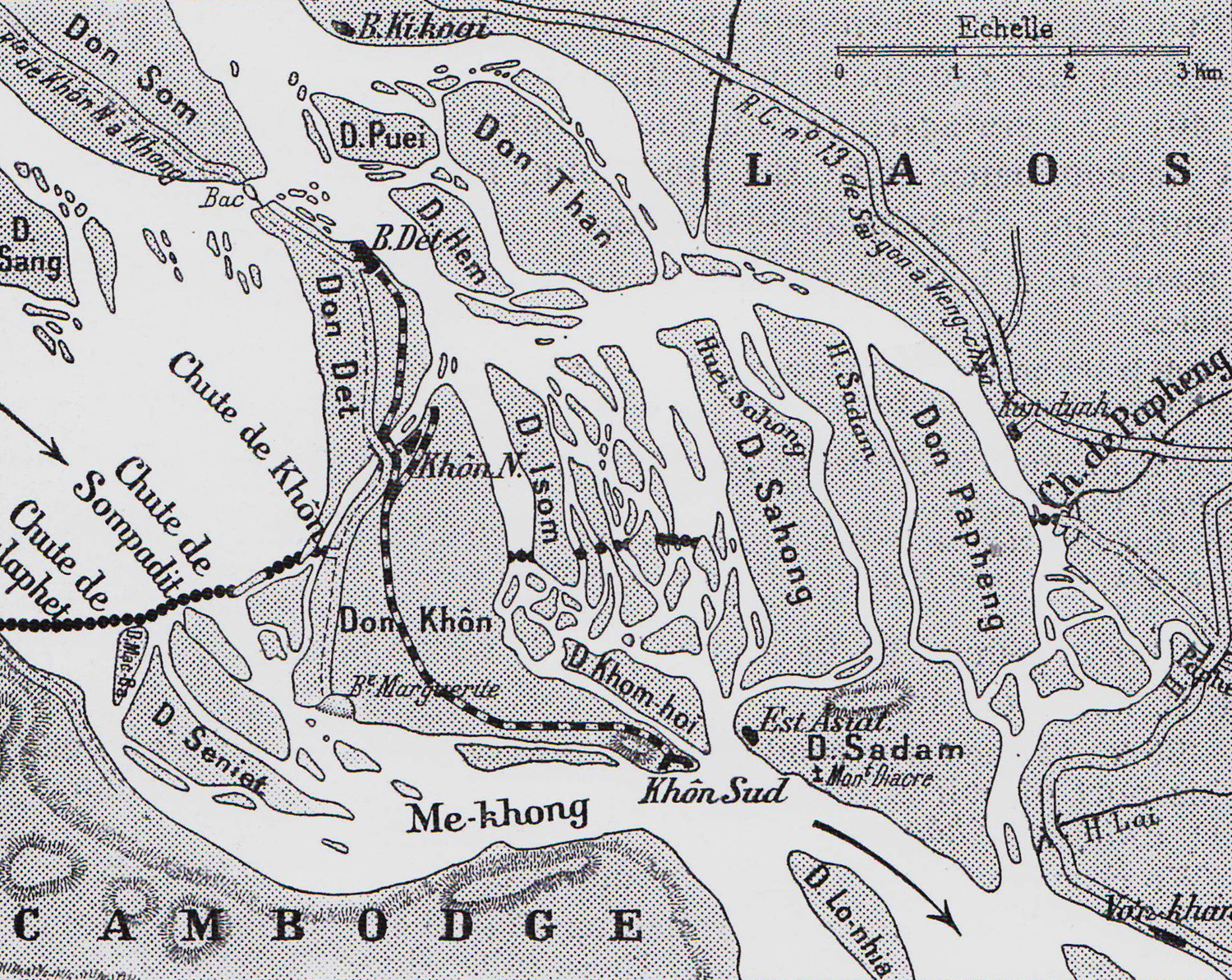

A map of the Khône island railway published in Madrolle, Indochine (1930)

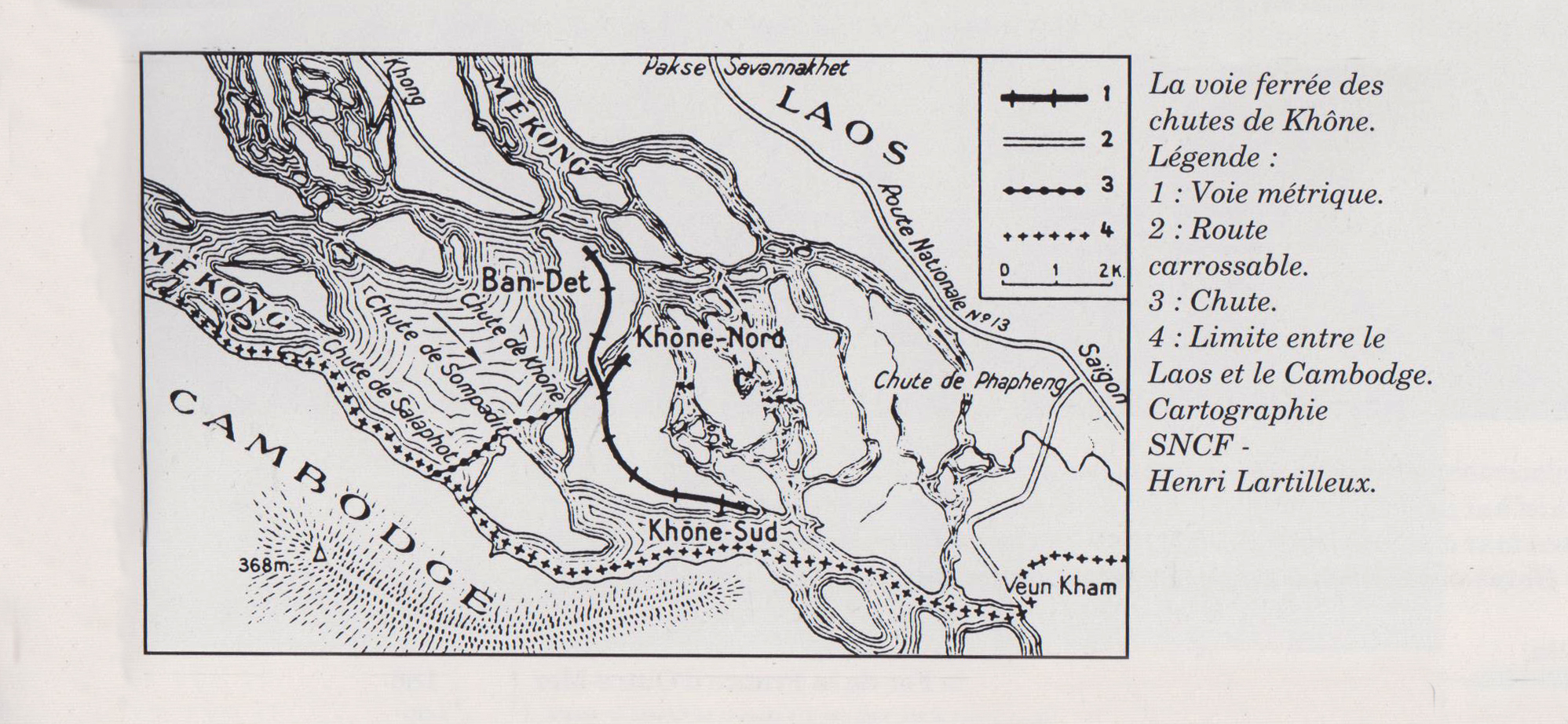

Henri Lartilleux’s SNCF map, published in Frédéric Hulot, Les Chemins de fer de la France d’Outre-mer, vol. 1: L’Indochine-Le Yunnan [The French overseas railways, vol. 1: Indochina-Yunnan]. Saint-Laurent-du-Var: La Régordane éditions, 1990

The steamboat “Ham-Luong” being transshipped by rail across Don-Khône Island in 1893

The gunboat “Massie” being relaunched above the falls at Khône Nord in October 1893

The steamboat “Garcerie” being transshipped by rail across Don-Khône island in 1896

Tim Doling is the author of The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, Bangkok, 2012) and also gives talks on Việt Nam railway history to visiting groups.

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group Rail Thing – Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam for more information about Việt Nam’s railway history and all the latest news from Vietnam Railways.

You may also be interested in these articles on the railways and tramways of Việt Nam, Cambodia and Laos:

A Relic of the Steam Railway Age in Da Nang

By Tram to Hoi An

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Vietnam Railways Building

Derailing Saigon’s 1966 Monorail Dream

Dong Nai Forestry Tramway

Full Steam Ahead on Cambodia’s Toll Royal Railway

Goodbye to Steam at Thai Nguyen Steel Works

Ha Noi Tramway Network

How Vietnam’s Railways Looked in 1927

Indochina Railways in 1928

“It Seems that One Network is being Stripped to Re-equip Another” – The Controversial CFI Locomotive Exchange of 1935-1936

Phu Ninh Giang-Cam Giang Tramway

Saigon Tramway Network

Saigon’s Rubber Line

The Changing Faces of Sai Gon Railway Station, 1885-1983

The Langbian Cog Railway

The Long Bien Bridge – “A Misshapen but Essential Component of Ha Noi’s Heritage”

The Lost Railway Works of Truong Thi

The Railway which Became an Aerial Tramway

The Saigon-My Tho Railway Line