A pousse-pousse travelling on the route stratégique or “High Road” (modern Trần Phú and Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai streets)

This article was published previously in Saigoneer http://saigoneer.com

An essential feature of life in early colonial Saigon, the Tour de l’Inspection was not so much a sunset promenade as an event designed to showcase wealth and power.

The origins of Saigon’s famous Tour de l’Inspection may be traced back to “La musique,” a Sunday afternoon military band concert held from the 1870s, either in the grounds of Botanical and Zoological Gardens or in front of the Cercle des Officiers [now the District 1 People’s Committee building at 47 Lê Duẩn].

A late 19th century image of Europeans leaving Saigon Cathedral after Mass

Usually attended by the Governor of Cochinchina and other high functionaries, “La musique” is described by several contemporaneous commentators as an event where members of colonial high society came to see and be seen, where the rich and powerful sought to outdo one another in lavishness and pomp, and where their wives could show off their latest fashions.

After the concert was finished, many of those attending “La musique” would set off in their carriages for a sunset promenade across the arroyo de l’Avalanche (Thị Nghè Creek) towards the north of the city. By the 1880s, this post-musique excursion had taken on a life of its own, becoming a daily after-work event which no self-respecting Saigonnais could miss.

The excursion became known as the Tour de l’Inspection, because the final destination of the earliest tours was the Inspection de Gia-Dinh, the French local government office which once stood on the site of today’s Bình Thạnh District People’s Committee.

A private horse-drawn carriage waits outside the villa of a European family in Saigon

Many writers of the period compare the Tour de l’Inspection to the contemporaneous “Tour du bois,” one of the most popular social phenomena in the French capital, which drew Parisians of all classes to promenade and meet with their peers in the Bois de Boulogne.

At around 5pm every evening, after the close of business, all the great and good of Saigon would gather outside the Botanical and Zoological Gardens. The entourage would then head out through Đa Kao, crossing the 3rd Bridge over the arroyo de l’Avalanche (Thị Nghè Creek) and continuing north along the “superbly straight and very well-maintained road” towards Gia Định.

During the early colonial period, the area north of the creek was still open countryside, intersected by a network of waterways, and the road to Gia Định, then known as the avenue de l’Inspection (today upper Đinh Tiên Hoàng street), was described as being “lined with trees and surrounded by flooded paddy fields.” Just before reaching Gia Định, it became a tradition for the promenaders to stop by the side of the road and “take the air,” while meeting and greeting their fellow travellers.

A pousse-pousse on a Saigon street

By the 1890s, the number of people taking the daily Tour de l’Inspection had increased significantly, and after the opening of the CFTI Saigon-Gò Vấp steam tramway in 1895, an alternative outward route across the 2nd Avalanche (road-tramway) bridge and north along rue Martin-des-Pallières (now Bùi Hữu Nghĩa street) was devised, making it possible to split the promenaders into two groups with a view to avoiding traffic jams.

After reaching the Inspection de Gia-Dinh and the nearby Lê Văn Duyệt Mausoleum, the original “classic” Tour de l’inspection took its participants east towards the Saigon river before circling back through Phú Mỹ. It then re-entered Saigon via the 1st Avalanche bridge (the Thị Nghe Bridge), returning to its starting point, the Botanical and Zooloigical Gardens.

However, during the same period, a longer Tour de l’inspection also became popular. After passing the Lê Văn Duyệt Mausoleum and Inspection de Gia-Dinh, this “grand promenade” took participants west along the route provincial (modern Phan Đăng Lưu and Hoàng Văn Thụ streets) to the Pigneau de Béhaine Mausoleum in Tan Sơn Nhất, and then headed southwest through the Plain of Tombs towards Chợ Lớn, finally returning to Saigon either along the route stratégique or “High Road” (modern Trần Phú and Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai streets) or via the “Low Road” which bordered the arroyo Chinois (Bến Nghé Creek).

During the early colonial period, the area north of the Thị Nghè creek was still open countryside

Many writers of the period describe the beauty of the countryside enjoyed by those taking the Tour de l’Inspection. In 1894, Henri Gallais commented: “Taking this sunset promenade outside the city in an open carriage, travelling through lush green forest on a beautiful starry and relatively cool night, it is truly reminiscent of a promenade in the Bois de Boulogne in the summertime.”

However, for many early colonial settlers, the Tour de l’Inspection was much more about flaunting wealth and power than about getting exercise or taking the air.

In 1896, Paul Troubat (L’Ile de Khong. Lettres laotiennes d’un engagé volontaire) described the Tour de l’Inspection as simply an excuse for the wealthy to impress others with their fine horses and carriages and for their spouses to show off their latest outfits, newly-delivered from Paris. “Everyone feels obliged to maintain a stiff, stilted attitude,” he remarked cynically. “Everyone is posing, but many of these people are trying to forget their origins, their more or less corrupt past, through arrogance and pride. Saigon society spends its time in jealousy and disparagement…. it is a very nice town from the physical point of view, but the character of the population can be ugly…”

Europeans being conveyed in a Malabar

In 1901, Jules Gervais-Courtellemont (Empire colonial de la France. L’Indo-Chine: Cochinchine, Cambodge, Laos, Annam, Tonkin) also criticised the laziness of colonial settlers who had “not yet learned to appreciate the charms of tennis and other sports so dear to English colonists,” preferring “to live the all too captivating life of coffee drinking, siestas and card games.” He pointed out that most colons’ idea of exercise was to do the traditional Tour de l’Inspection while “lounging lazily on cushions in their Victoria carriages, dressed in the latest fashionable Paris outfits.”

With the arrival of the motor vehicle and the steady urbanisation of Saigon’s northern and western suburbs in the early 20th century, members of Saigon’s colonial high society gradually abandoned the Tour de l’Inspection as a vehicle for impressing their peers.

In his 1932 book Christiane de Saïgon, B Grasset wrote that, while the older generation of colonial settlers might regret passing of the traditional Tour d’Inspection with its horse-drawn carriages and malabars, the colonial social scene in Saigon was now firmly focused on rue Catinat [Đồng Khởi street], where the rich and powerful “could show off their motor cars and fashionable costumes as many as 20 times between one end of the street and the other… before holding court at the trendy Continental Hotel Terrace, the heart of the city and of Indochinese life.” He continued: “Only here does one now gather to gossip and do business, to talk of love and money, and to learn the news from Europe and Asia from passengers making a three-day stopover on the major courier ships.”

The Bình Lợi bridge, westernmost point of the Tour de l’Inspection, at the beginning of the age of the automobile

Yet despite this shift, the Tour de l’Inspection did not disappear immediately. As horse-drawn carriages gave way to the first mass-produced motor vehicles, the “grand promenade” began to appear in Madrolle and other guidebooks as a tourist attraction.

The last known reference to the Tour de l’Inspection appears in the 1933 Guide pratique. Saïgon, which describes it as follows:

“The Tour de l’Inspection is a circular route which borders territories of Saigon, Gia-Dinh and Cholon (20 km approximately), which leaves the city by the Phu-My Bridge on the arroyo d’Avalanche, or by the Dakao Bridge. It crosses through Gia-Dinh and, via a beautiful shaded road lined with quaint buildings, arrives at the tomb of Le Van Duyet, famous general of King Gia Long, before continuing to the tomb of the Bishop of Adran, which is very interesting for the visitor. Close by is the aerodrome of Tan-Son-Nhut and the buildings of the Service des Haras (Government Stud Farm). A little further on, it passes the battlefield of Chi-Hoa, the Plain of Tombs and the TSF (Telephonie sans fil) station at Phu-Tho. Finally, it reaches Cholon, an industrial and commercial city crowded with Chinese, which is very picturesque at night, and interesting to visit in detail. The tour returns to Saigon, either by the boulevard Frédéric-Drouhet [now Hùng Vương street], which is the Cholon extension of rue Chasseloup-Laubat[now Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai street].”

While some of the colonial-era attractions no longer exist, parts of the famous Tour de l’Inspection still feature in several Hồ Chí Minh City tourist itineraries today.

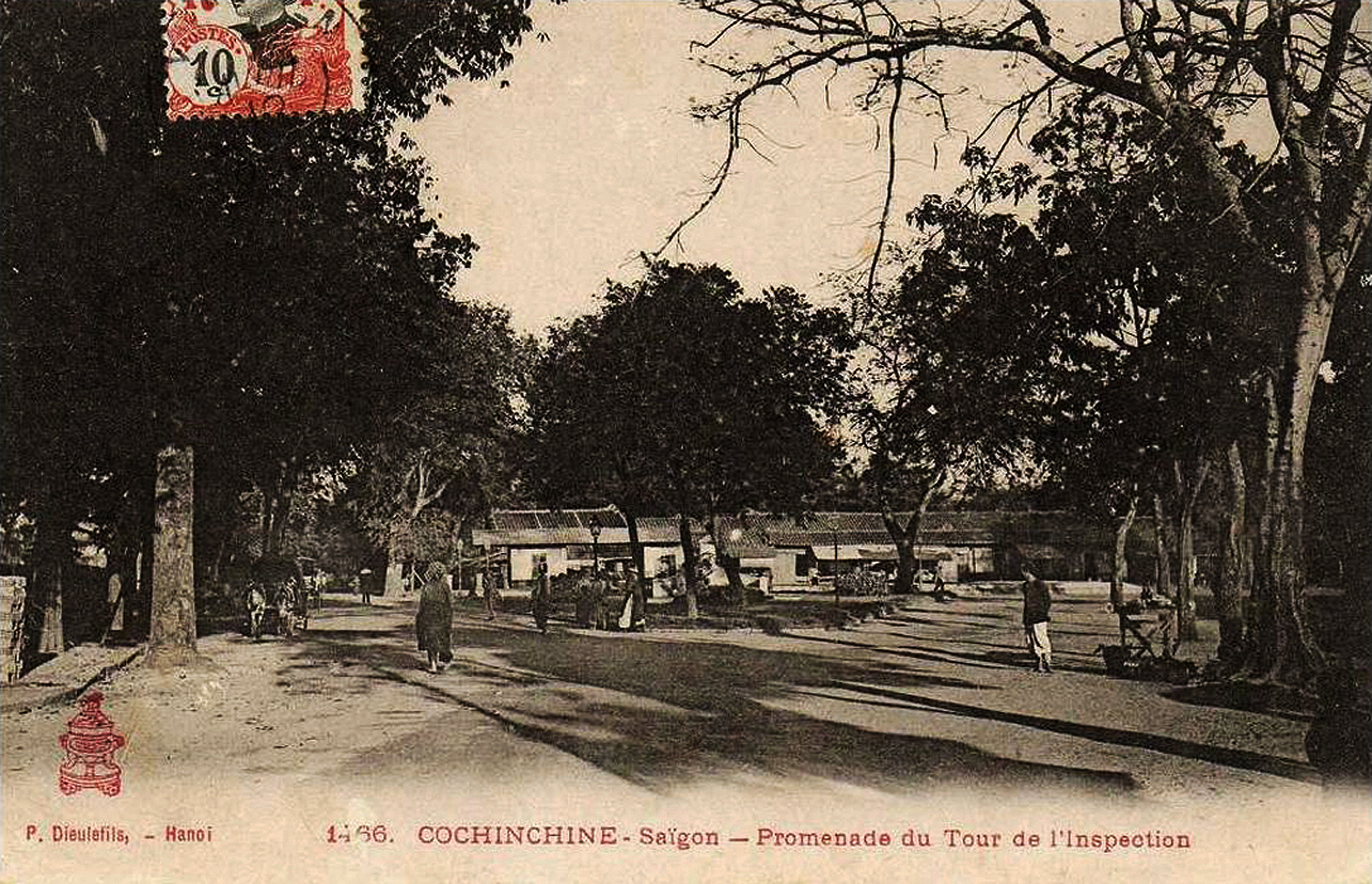

Saigon – Promenade du Tour de l’Inspection

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.