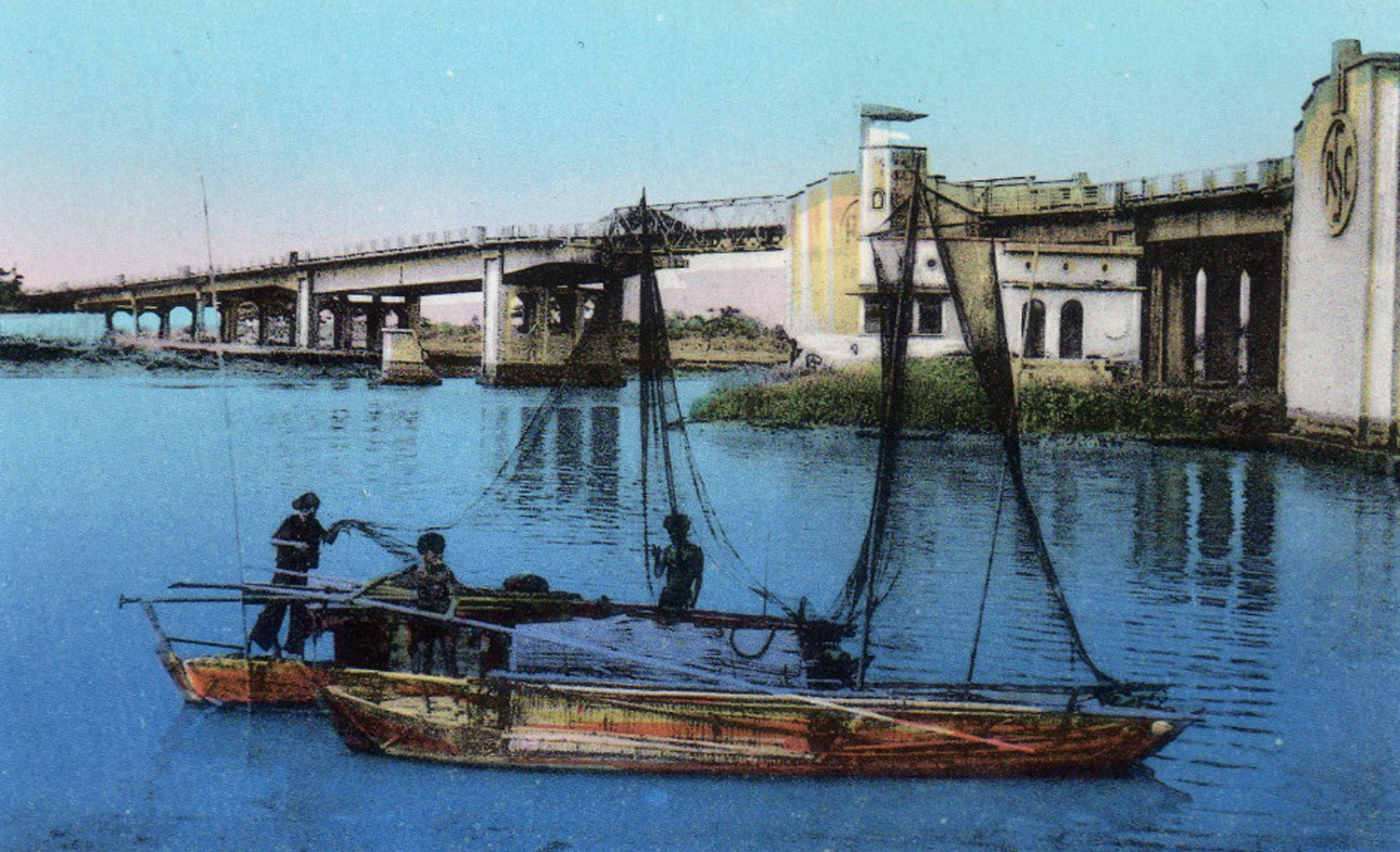

The “Y” Bridge in the 1940s

This article was published previously in Saigoneer http://saigoneer.com

Built by the French during the latter years of the colonial era, Chợ Lớn’s “Y” Bridge became the focus of several important battles during the two Indochina Wars.

An aerial view of the “Y” Bridge in 1950

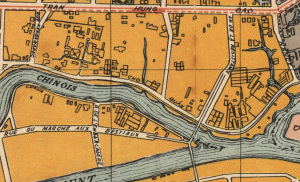

The “Y” Bridge was originally conceived by the French in 1937 as part of a scheme to build a new municipal abbatoir in Chánh Hưng, immediately south of the existing Arroyo Chinois (Bến Nghé/Tàu Hủ creek) in what is now District 8. Known to the French as the pont Tripode or pont en Y, the bridge formed a crucial part of this scheme, because the construction of the “Canal de dérivation” in 1906 and of the “Canal de doublement” in 1919 to relieve congestion on the Arroyo Chinois had left much of the Chánh Hưng area ringed by waterways.

The design was drawn up by modernist architect René Nguyễn Khắc Schéou, and in 1938 the Cochinchina authorities voted just over 400,000 piastres from their regional budget to pay for the construction of the bridge. Then on 28 October 1939, according to the Bulletin économique de l’Indo-Chine, “Mr Governor General Brévié laid the first stone of the pont Tripode to serve the future slaughterhouse.”

The “Y” Bridge marked on a 1952 map

In the wake of the Japanese invasion of 1940, construction of the bridge was placed on hold, but work eventually resumed and the pont Tripode was inaugurated on 20 August 1941. In the words of a Vichy government press release of 23 September 1941, “Its construction, carried out despite the circumstances, is a symbol of our constructiveness and confidence in the future. It meets multiple needs and will enable Greater Cholon to develop. With a length of 90 metres and a deck 8 metres wide, it required 8,900 tons of steel and more than 4,000 cubic metres of reinforced concrete for its construction. Its lateral and access roads required an additional 7,099 cubic metres of fill.”

Apart from its unusual configuration, the “Y” Bridge was regarded at the time of construction as a utilitarian work, and it may have lapsed into obscurity had it not been for the various battles which took place in its vicinity during the two Indochina Wars.

The “Y” Bridge in 1968

From as early as the 1920s, the neighbourhood immediately south of the bridge harboured various bands of thieves and outlaws. By the 1940s, it had become home to the Bình Xuyên, an organised coalition of gangs involved in racketeering, petty crime, river piracy and kidnapping.

After World War II, the Bình Xuyên emerged as a powerful military and political force, initially allying itself with the Việt Minh and staging a vigorous defence of the “Y” Bridge from 24 September until early October 1945 in order to prevent returning French troops from reoccupying the southern part of the city.

However, in 1947 it switched allegiance, offering money and military support to the French authorities and later to the State of Viêt Nam in exchange for legal recognition of its gambling, prostitution, money laundering and opium trafficking activities.

Following his rise to power in the spring of 1955, President Ngô Đình Diệm resolved to crush the Bình Xuyên, and during the subsequent “Battle for Saigon” (28 April-3 May 1955), VNA forces attacked its base of operations in Chợ Lớn, blowing up part of the “Y” Bridge to prevent Bình Xuyên reinforcements from entering Saigon. By the end of this operation, Bình Xuyên forces had been routed and driven from the city.

“Smoke rises from the southwestern part of Saigon on 7 May 1968 as residents stream across the “Y” Bridge to escape heavy fighting between the VC and South Vietnamese soldiers.” (AP Photo)

The “Y” Bridge was subsequently repaired, and in late May 1968 it once more became a battlefield during the National Liberation Front’s “Mini Tet” Offensive.

During six days of intense house-to-house fighting, the area around the bridge was devastated, but the bridge itself remained intact.

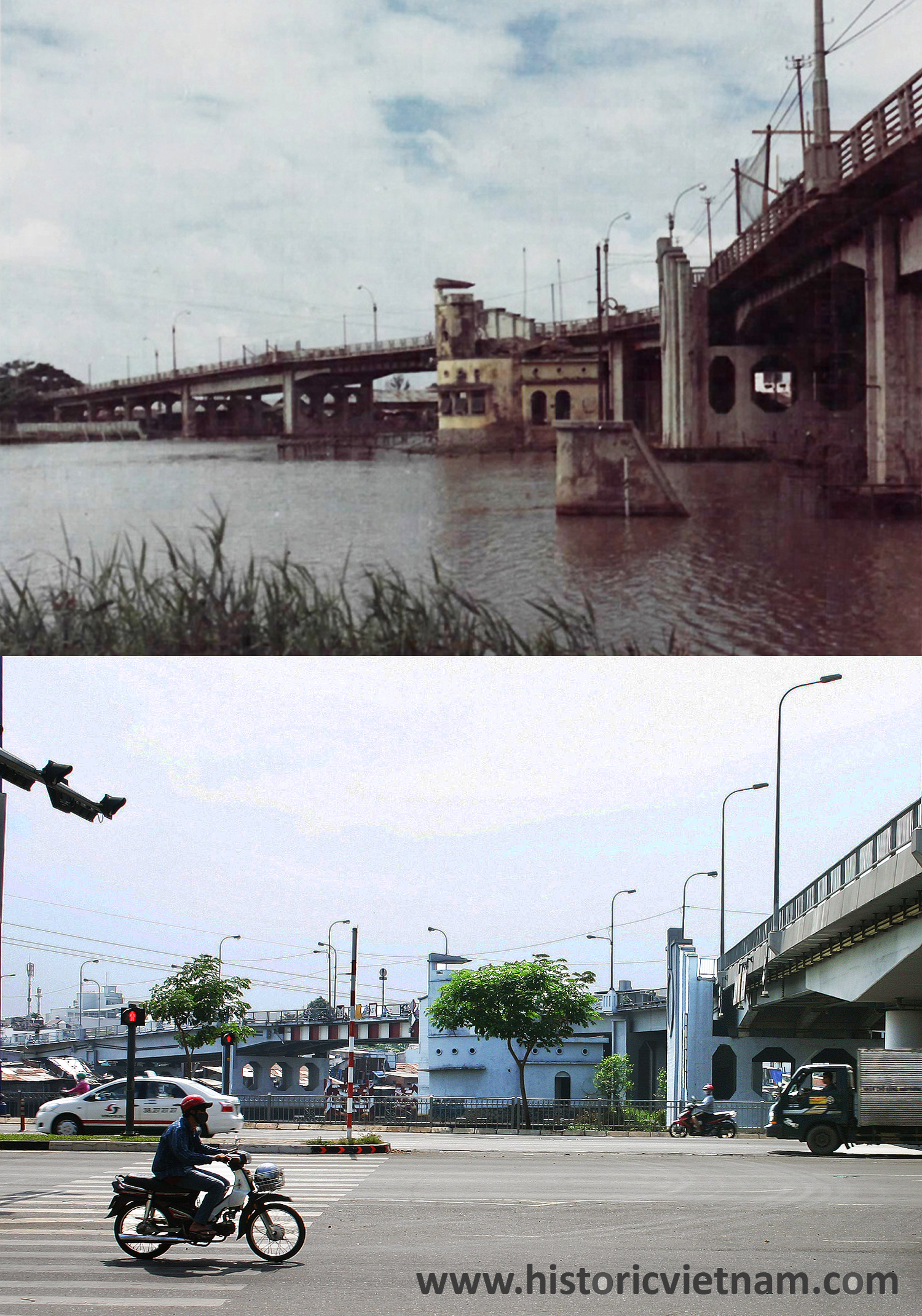

Refurbished in 1992, the old bridge was completely rebuilt in 2007 to permit higher clearance over the East-West Highway, retaining the original columns and abutments.

The “Y” Bridge in 2015 viewed from the East-West Highway

Traffic approaching the centre of the “Y” Bridge in 2015

The Y Bridge Then and Now

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.