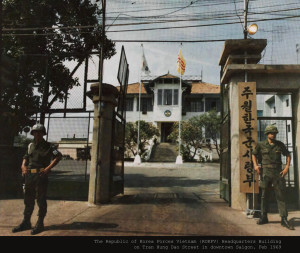

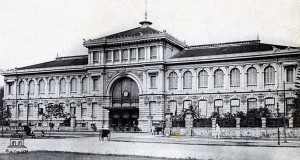

The main entrance to the Trần Phú Memorial Museum at Hồ Chí Minh City’s Chợ Quán Hospital

A Hospital for Tropical Diseases is perhaps not the most obvious visitor attraction, but a national historic site within the grounds of Hồ Chí Minh City’s Chợ Quán Hospital is worth a visit.

Founded in 1864 and managed until 1909 by the Sisters of Saint-Paul de Chartres, Chợ Quán Hospital, now known as the Hospital for Tropical Diseases (Bệnh viện Bệnh Nhiệt đới), is the oldest hospital in Hồ Chí Minh City.

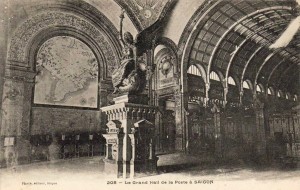

Inside the old secure psychiatric ward building

Focusing initially on the treatment of infectious diseases, it began specialising after 1904 in mental illness. Today this specialism is handled by the Psychiatric Hospital (Bệnh viện Tâm thần), located on the same campus.

As opposition to French rule intensified during the last few decades of colonial rule, the prison system became increasingly overcrowded, obliging the authorities to convert other public buildings into jails. One such building was the secure psychiatric ward at Chợ Quán Hospital, which by the late 1920s doubled as a jail where political prisoners were held for interrogation.

A group cell with a raised platform for the inmates to lie on with their legs in shackles

In the 1980s that ward was restored in period style and today it is open to the public as a small museum, dedicated primarily to the memory of its most famous inmate, Trần Phú, first Secretary General of the Indochina Communist Party.

Trần Phú (1904-1931) was born on 1 May 1904 at An Thổ village in Tuy An district of Phú Yên province. The son of a minor official, he attended the National School in Huế where his brilliant intellect soon became apparent. After co-founding the Việt Nam Revolutionary Party (Việt Nam Cách mạng Đảng) in 1925, Phú went to Guangzhou in the following year to negotiate his party’s merger with Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s Việt Nam Revolutionary Youth Association (Hội Việt Nam Cách mạng Thanh niên).

Trần Phú (1904-1931)

In 1927 he went to the Soviet Union to study Marxist-Leninist doctrine at the Eastern University in Moscow and in the following year he attended the sixth session of Communist International. When the Indochina Communist Party (Đông Dương Cộng sản Đảng) was set up in October 1930, Trần Phú was elected as its first Secretary General.

Trần Phú was among several members of the Indochina Communist Party tried and convicted in absentia by a court in Nghệ An on 11 October 1929. Captured by French police on 18 April 1931 while visiting the Party’s printing house at 66 rue Champagne (now 66 Lý Chính Thắng) in Sài Gòn, he was detained in several different locations before being moved to the secure psychiatric ward at Chợ Quán Hospital on 26 August 1931.

The cell where Trần Phú died on 6 September 1931, aged just 27

On his third day at the hospital he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and transferred into the isolation ward. He died 11 days later on 6 September 1931, aged just 27.

Many other revolutionaries were incarcerated at Chợ Quán Hospital during the years of resistance against France, including Hà Huy Tập and Trần Não. Another of its famous inmates was the founder of the Hòa Hảo sect, Huỳnh Phú Sổ (1920–1947), who was incarcerated here from 1940-1941 and is said to have converted his psychiatrist, Dr Tam to the Hòa Hảo faith.

After 1955 the South Vietnamese authorities continued to use the south wing of the prison ward to intern political prisoners.

In 1976 the old prison ward once more became part of the main hospital, but in the 1980s, because of its historic association with the revolutionary struggle, it was declared a historic site.

The Trần Phú Memorial Museum is located within the Chợ Quán Hospital compound, around 200 metres from the main entrance gate.

The yard in front of the building has been converted into a small memorial garden with a bust of Trần Phú and a stele in Vietnamese which reads:

The yard in front of the building has been converted into a small memorial garden with a bust of Trần Phú and a stele in Vietnamese which reads:

Mr Trần Phú, Secretary General of the Indochina Communist Party (now the Communist Party of Việt Nam), born 1.5.1904, sacrificed 6.9 1931 in this prison.

Before he passed away, he reminded his comrades: “Remain determined to fight.”

His last words tell of the heroic mettle of the communists who never succumbed to the violence of the enemy in whatever situation they found themselves. These words became a powerful weapon for the Vietnamese people to wield against enemy forces, helping them to overcome difficulties on the revolutionary road.

The former secure psychiatric ward – a U-shaped building with bare concrete walls and a tiled floor – is divided into both individual and group cells, each with a raised platform for the inmate or inmates to lie on with their legs in shackles.

Another of the group cells in the former secure psychiatric ward

The door of each room has a small peephole through which guards could monitor the activities of the inmates inside.

The main section of the prison ward contains a narrow area for female prisoners at the front and behind it a larger area for male prisoners. The female area contains three large cells, two individual cells, two windowless solitary confinement spaces and a bathroom, while the male area contains three large cells, one individual cell, two windowless solitary confinement spaces and a bathroom.

When Trần Phú first arrived at Chợ Quán Hospital, he was detained in the largest of the three main cells in the male section, along with around 20 other activists.

The south wing, used to intern political prisoners during the period 1955-1975

The north wing was once the isolation ward (Khu cách ly) and is made up of two large cells, four individual cells, two windowless solitary confinement spaces and two bathrooms. After it was discovered that Trần Phú had contracted tuberculosis, he was placed in one of the large cells here, together with fellow revolutionaries Nguyễn Văn Nhung and Châu Văn Sanh. When his condition worsened, he was moved into one of the individual cells and it was there that he died. A small shrine has been set up in his memory and memorial rites are often performed.

The south wing of the prison ward (Khu biệt giam) was the main area used to intern political prisoners during the period 1955-1975. Part of that wing has been turned into an exhibition facility containing photographs and documents (in Vietnamese only) recounting the history of the site and the life of Trần Phú. Visitors can also view two large and two small cells in the rear section of this wing.

The Trần Phú Memorial Museum at Chợ Quán Hospital was recognised as a national historic monument by the Ministry of Culture and Information on 16 November 1988.

Getting there

Address: Khu trại giam Bệnh viện Chợ Quán – Nơi đồng chí Trần Phú hy sinh, Bệnh viện Chợ Quán, 766 Võ Văn Kiệt, Phường 1, Quận 5, Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh

Directions: Entering the main gate, take the lane immediately to the right of the large sign containing the plan of the hospital – a signpost on a nearby tree tells you that this road leads to the Đơn vị khám chuyên khoa gan (Specialist Liver Unit). If you walk down this road (in front of the Bách Hóa Canteen) you will find the Trần Phú Memorial Site compound a bit further along on the right hand side, surrounded by flags.

Telephone: 84 (0) 16 5250 6566

Opening hours: On request 8am-11am, 2pm-4.30pm daily

Admission: free of charge

See also Off the Tourist Trail in Saigon – The People’s Army Delegation HQ

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.