Đỗ Hữu Phương (1841-1914) pictured in the late 1890s after his retirement

One of the most famous mandarins of the early French period, Đỗ Hữu Phương (1841-1914) became the second richest man in Cochinchina…. and dinner at his palatial residence in Chợ Lớn was once one of the most sought-after invites of the day.

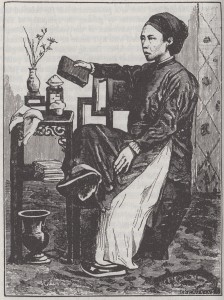

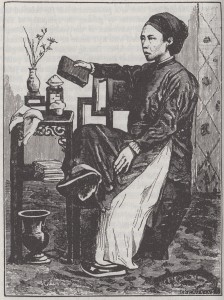

Đỗ Hữu Phương (1841-1914) pictured in the early 1880s (from Charles Lemire, l’Indochine, Paris, 1884)

Born in 1841 at Chợ Đũi (Saigon), Đỗ Hữu Phương was the eldest son of a regional government mandarin from the mixed-race (Vietnamese-Chinese) Minh Hương community and grew up speaking fluent Vietnamese and Chinese. His early education at a French mission school also gave him a grounding in French which served him well in his later career.

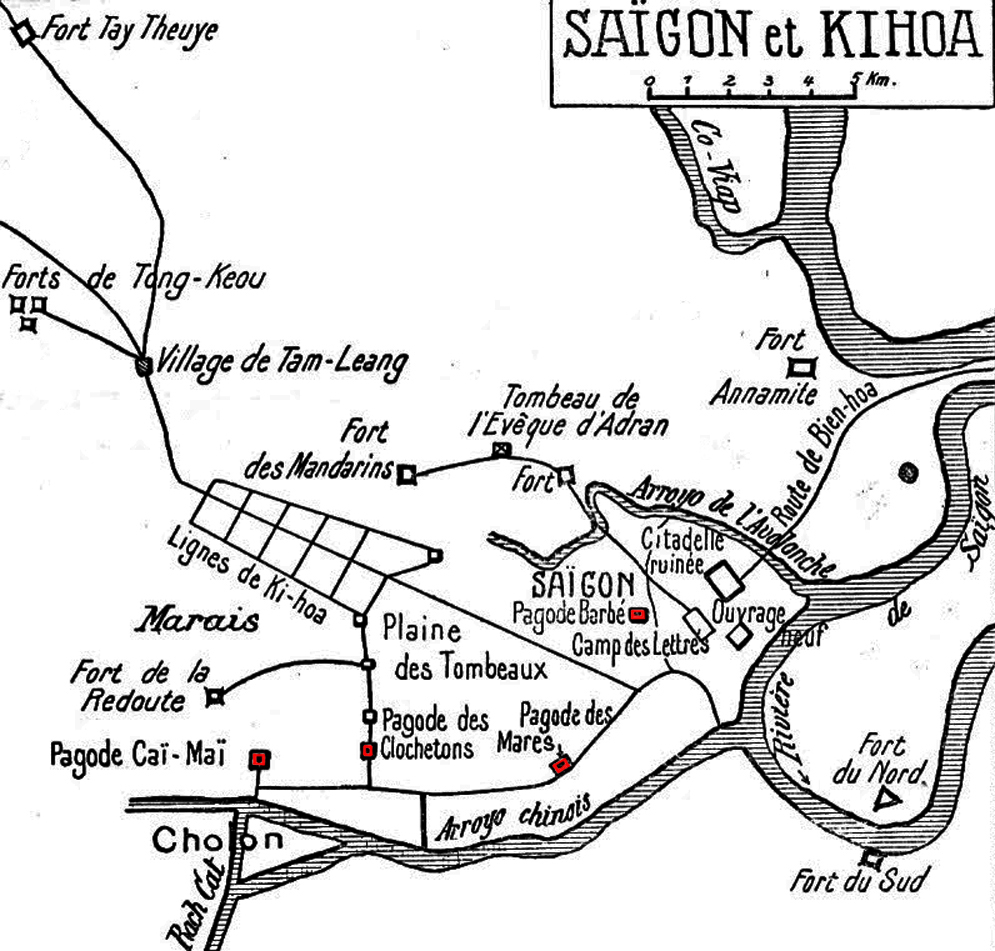

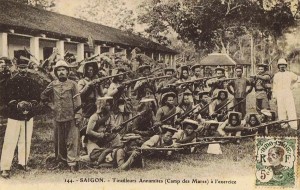

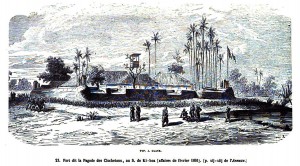

When French forces attacked Saigon in 1859, Phương initially participated in the resistance, but following the decisive 1861 French victory at the “Lignes de Khi-Hoa” (Chí Hòa), he “rallied to the French cause” and became a colonial militia leader.

In subsequent years, Phương took part in a number of key engagements as the French extended their control over the six provinces of the south, including the retaking of Rạch Giá from Nguyễn Trung Trực in June 1868.

Phương’s career as a colonial mandarin began in earnest in 1865, when he was rewarded for his loyalty with the post of Hộ trưởng and made responsible for law and order in Chợ Lớn. In 1872 he became a member of the Chợ Lớn Municipal Council and later that year he was appointed Đốc phủ (governor). Promotion to Đốc phủ sử (provincial governor) followed.

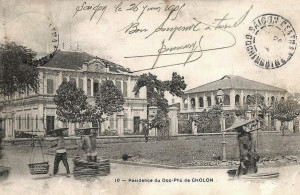

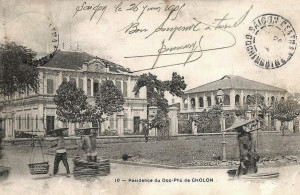

The palatial residence of “Tổng đốc” Đỗ Hữu Phương, pictured at the turn of the century

It was during this period, according to the popular late 19th-century saying Nhất Sỹ, nhì Phương, tam Xường, tứ Hỏa – “First Sỹ, second Phương; third Xường and fourth Hỏa” – that Phương became the second richest man in the south. His wealth was accumulated, not from trade and commerce, but by skilfully exploiting his close links with senior colonial administrators to function as an intermediary between Chợ Lớn’s leading Chinese merchant houses and the French civil service.

During this period he is said to have amassed large tracts of land in what is now District 8 – the Ông (Mr) in the names rạch Ông Lớn, cầu Rạch Ông and chợ Rạch Ông is believed to refer deferentially to Đỗ Hữu Phương, the former landlord of that area.

In subsequent years, Phương eagerly adopted a quasi-French lifestyle, assiduously cultivating the image of a man who “moved at ease and confidence through a life that was half Vietnamese and half French.”

When the colonial authorities issued a decree in 1881 permitting the naturalisation of Vietnamese citizens, Phương was one of the first to apply. In 1883, following the establishment of the Société des études indochinoises in Saigon, Phương was elected as its first president and for several years acted as the editor of its French-language journal.

When the colonial authorities issued a decree in 1881 permitting the naturalisation of Vietnamese citizens, Phương was one of the first to apply. In 1883, following the establishment of the Société des études indochinoises in Saigon, Phương was elected as its first president and for several years acted as the editor of its French-language journal.

Phương made extended visits to France on no less than four occasions (1878, 1884, 1889 and 1894), prompting the scholar Trương Minh Ký (1855-1900) to write a satirical poem in Vietnamese which described Phương sitting in the Café de la paix in Paris, chatting with leading colonial personages such as Bonnet, Blanchy and Morin.

Today, Đỗ Hữu Phương is remembered above all as the genial host who invited many high-ranking French colonial settlers into his home and introduced them to the joys of Vietnamese cuisine.

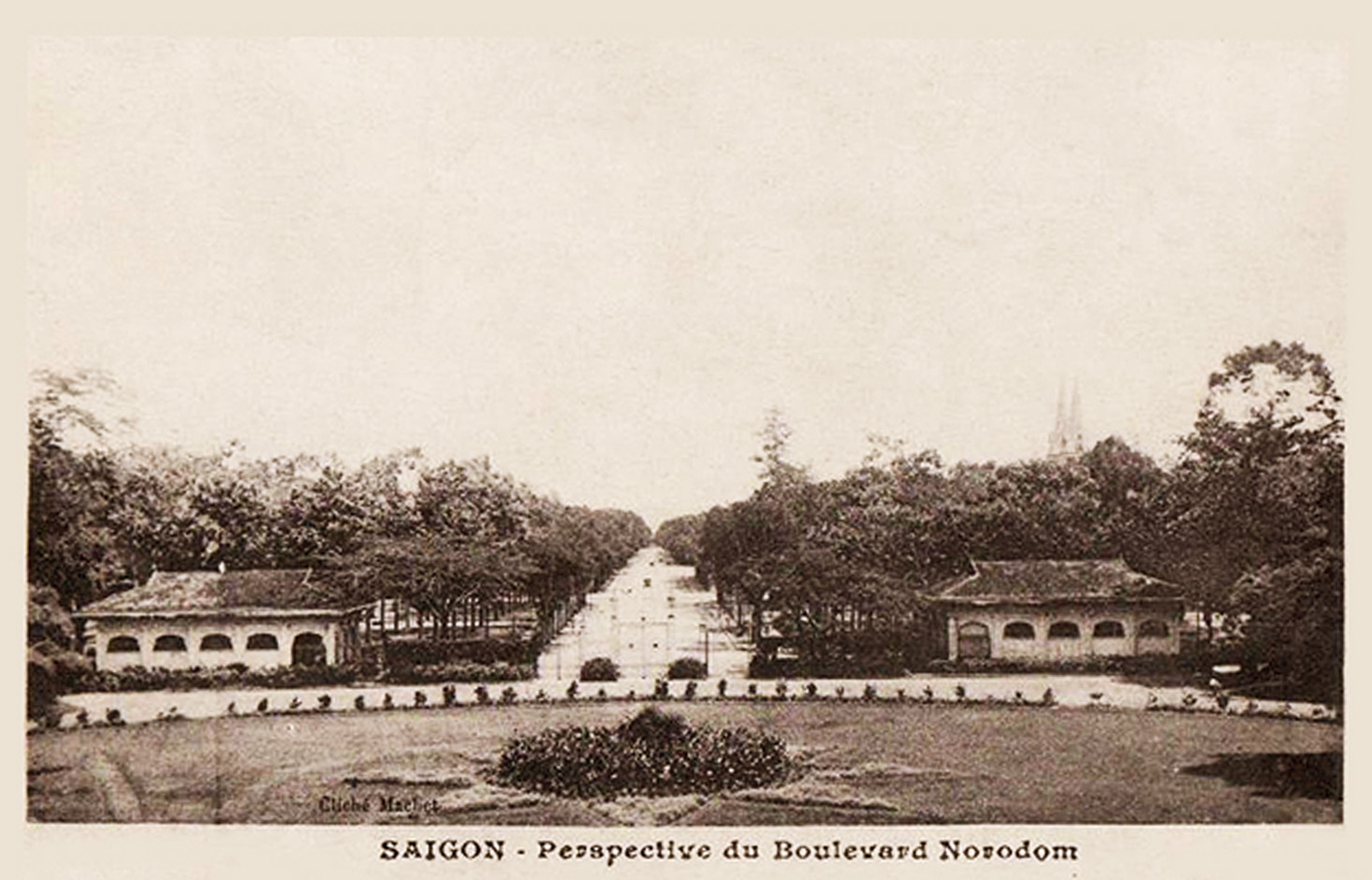

In the late 1870s or early 1880s, Phương built himself a palatial home on quai Testard (the former Phố Xếp canal, now Châu Văn Liêm street). Comprising buildings of both colonial and traditional design surrounding a central courtyard, this subsequently became a must-see destination for many French visitors and expatriates.

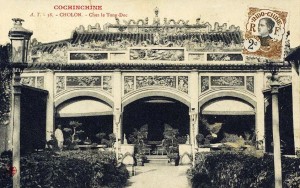

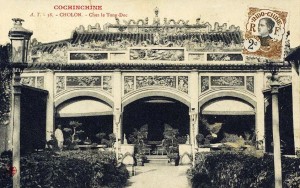

The family temple of “Tổng đốc” Đỗ Hữu Phương’s residence

Several French writers of the period wax lyrical about the beauty of Phương’s “princely residence,” in particular the family temple, an “incomparable work” which “surpasses the imagination” with its intricately carved and inlaid wooden panels and “beautifully decorated roof supported by columns of hard black wood, each formed from a single tree trunk and carved with scenes featuring characters of the greatest fineness.” Apart from the family shrine, the temple building is said to have housed “a real museum of antiques,” including large quantities of “old and very beautiful inlaid furniture.”

By the 1890s, however, the real attraction here was not the residence itself, but the lavish Vietnamese banquets hosted in it. After 1893, an invitation to dine with Phương seems to have become one of the hottest tickets in colonial Saigon-Chợ Lớn – his dinner guests included all the great and the good of colonial society, including Governor General Paul Doumer (1897-1902), who became a close family friend. Phương’s banquets became the stuff of legend and were described in numerous French travel books and journals of the period, including the review Tour du Monde (1893), Alfred Coussot’s Douze mois chez les sauvages du Laos (1898) and George Dürrwell’s Ma chère Cochinchine, trente années d’impressions et de souvenirs, 1881-1910.

In her Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam: Food and Drink in the Long Nineteenth Century (2012), Erica Peters argues that by introducing his high-ranking guests to Vietnamese cuisine, Đỗ Hữu Phương “shook up colonial assumptions, pushing his French guests to reconsider their obsession with eating French food in the colony.”

Đỗ Hữu Phương (1841-1914) pictured in the late 1890s after his retirement

Writing in 1897, Alfred Coussot describes in slightly shocked tones how he and his fellow diners were encouraged to eat their “first ever exclusively Annamite [Vietnamese] meal” with “ no cutlery and no bread,” but with “traditional chopsticks and rice bowls” – something hitherto regarded as unthinkable for most colonial settlers. Contemporary French accounts of the cuisine offered at Phương’s table not surprisingly focus on the more exotic dishes offered, such as “grilled palm tree grubs” and “still-born pig,” noting, nonetheless, that Phương would take pity on those with a less adventurous palate by serving them huge steaks cooked in the western style, thereby ensuring that everyone left his home satisfied.

Đỗ Hữu Phương was made a Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur in 1872, an Officier de la Légion d’honneur in 1881 and a Commandeur de la Légion d’honneur in 1890. However, perhaps the apotheosis of his career as a colonial mandarin was the honorific post of Tổng đốc (general governor), bestowed on him by the French authorities to mark his retirement in 1897. At this time, the boulevard on which his residence was located was named rue Tong-Doc-Phuong, a name it retained right down to 1955.

Throughout his life, “Tổng đốc” Phương spent much of his time engaged in charitable work. One of his particular interests was the establishment of a school for Vietnamese girls in Saigon, and it was largely thanks to Phương’s influence and philanthropy that the Collège de jeunes filles indigènes (later the Lycée Gia Long, now the Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai Secondary School on Điện Biên Phủ street) was founded in 1915.

Đỗ Hữu Phương also funded the 1879 construction work which transformed an old communal house into the Nghĩa Nhuận Assembly Hall, one of Chợ Lớn’s most elegant Minh Hương temples at 27 quai de la Distillerie (now 27 Phan Văn Khỏe). His sons would later continue to make regular donations towards its upkeep throughout the colonial period.

Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai Secondary School owes its existence to Đỗ Hữu Phương

Đỗ Hữu Phương died of pleurisy on 3 April 1914. His grand public funeral on 19 April was attended by “almost the entire European settlement and a huge Asian crowd”…. “all Annamite dignitaries and notables were present” and an address was given by Joost van Vollenhoven, Secretary general of the Cochinchina government.

Đỗ Hữu Phương and his wife Trần Thị Điều (1842-1921) had four sons and two daughters.

Two of his sons remained in Cochinchina – Đỗ Hữu Trí became a magistrate, while Đỗ Hữu Tỉnh worked in the colonial Treasury. Meanwhile, Phương’s two daughters, who were both well educated and spoke fluent French, are said to have mixed widely in colonial society. One, Đỗ Thị Nhàn, later married the Hà Đông governor Hoàng Trọng Phu (1872-1946).

However, his other two sons, Đỗ Hữu Chẩn (1872-1955) and Đỗ Hữu Vị (1883-1916), are best remembered today. Both were educated at private schools in France and both graduated from the famous Saint-Cyr military academy.

Đỗ Hữu Chẩn became a colonel in the French colonial infantry, serving in Tonkin and Algeria before being sent to the front in World War I. A Commandeur de la Légion d’honneur who received the Croix de guerre for bravery, Chẩn served after the war as a military chief of staff in Rouen.

Đỗ Hữu Phương’s famous aviator son Đỗ Hữu Vị (right), pictured in France in early 1915

Đỗ Hữu Phương’s most famous offspring was Đỗ Hữu Vị, still celebrated today as Việt Nam’s first pilot. After an early military career with the French Foreign Legion in Morocco, he retrained as an aviator in 1910 and became one of the pioneers of military aviation in Morocco – to this day, a street in Casablanca still bears his name. On the outbreak of World War I, Vị was posted to France, where he flew several missions before a crash in 1915 left him severely crippled and no longer able to fly. Rejoining the French Foreign Legion, he served briefly in the trenches of the Somme as commander of the 7th Company, but was killed on 9 July 1916 while leading his troops into battle. Initially buried in France, his remains were returned to Cochinchina in 1921 and reburied with great ceremony in the family plot on the Plaine des tombeaux (Plain of tombs), modern District 10.

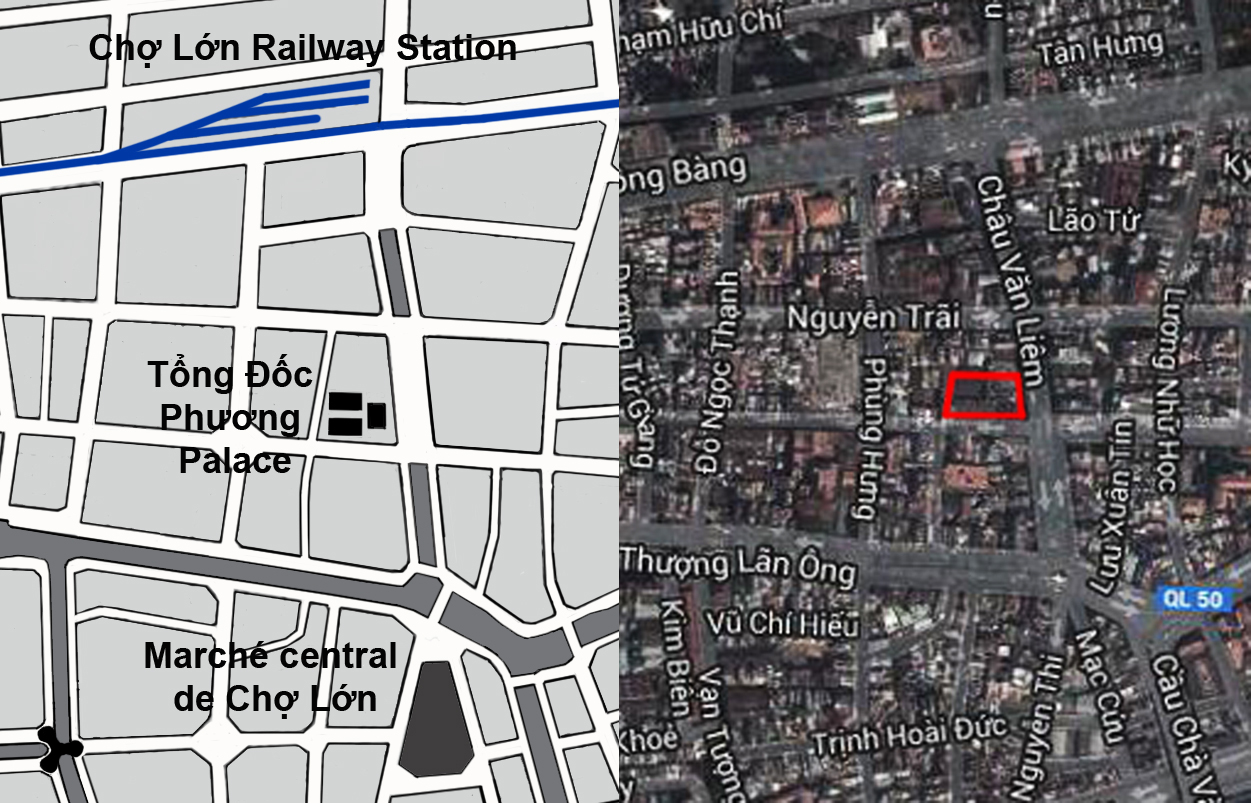

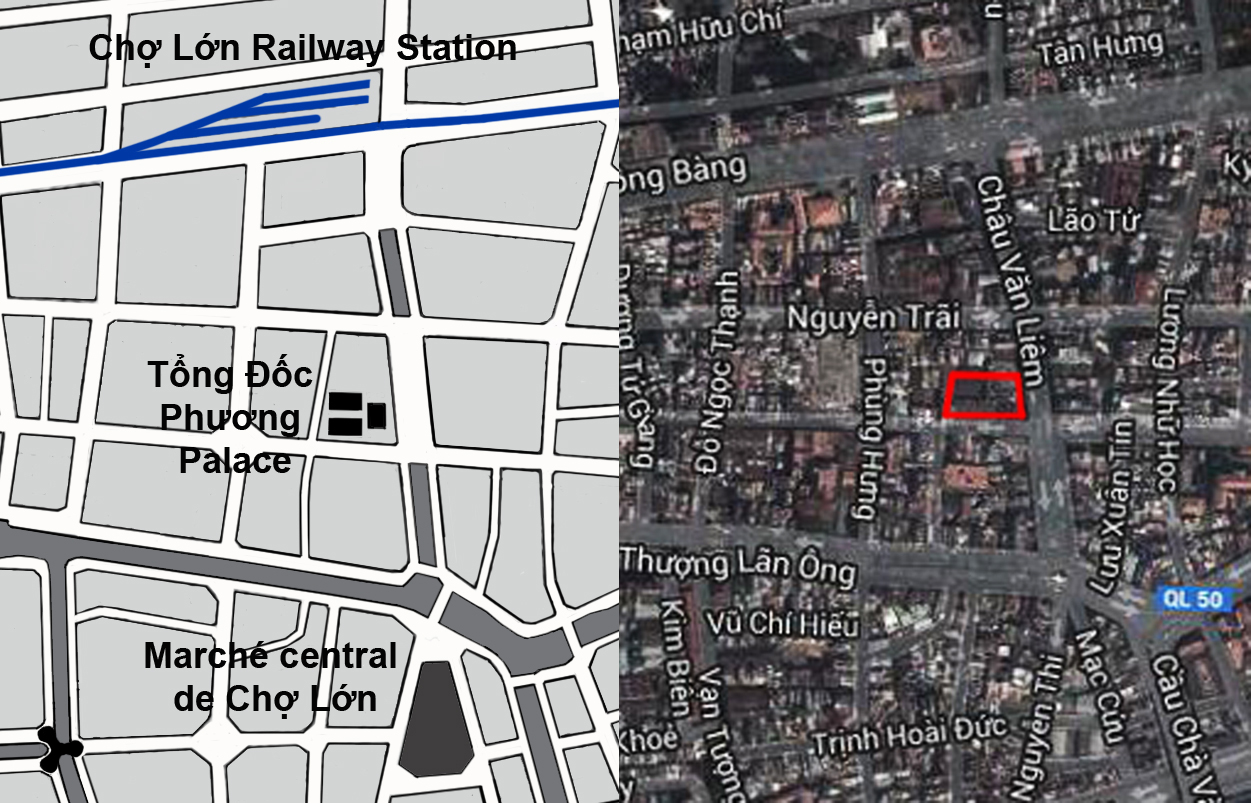

After the death of Đỗ Hữu Phương’s wife in 1921, the family decided to sell the palatial mansion on rue Tong-Doc-Phuong in Chợ Lớn and in subsequent years it was demolished so that the whole block could be redeveloped. Today there is little to suggest that this extraordinary complex ever existed, apart from one of the former out-houses which may still be seen in an alley off Trần Hưng Đạo B street.

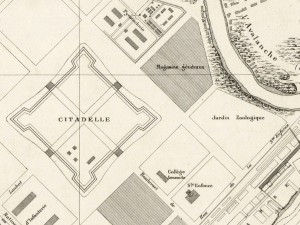

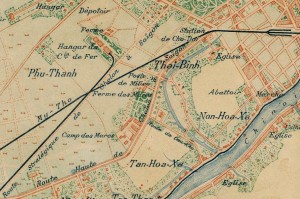

A map (left) showing the location of Đỗ Hữu Phương’s residence on quai Testard in the 1890s and a Google map (right) showing the same location today

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.