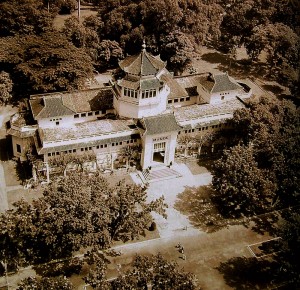

The Catinat Building today

This article was published previously in Saigoneer http://saigoneer.com

According to a recent article in the Dân trí newspaper, the Catinat Building at the corner of Đồng Khởi and Lý Tự Trọng streets sits on a so-called “gold land” block which has been earmarked for redevelopment to accommodate “services, culture, luxury hotels, finance offices, exhibition areas.” While it’s still standing, we take a look at the history of this old art deco landmark.

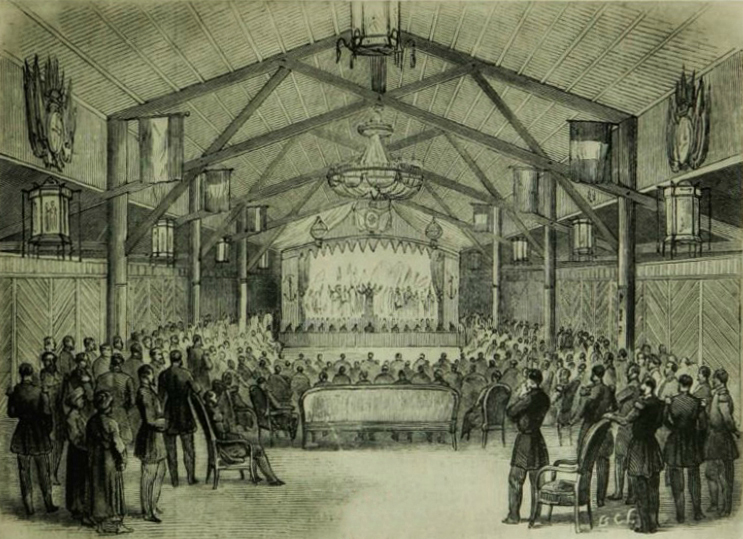

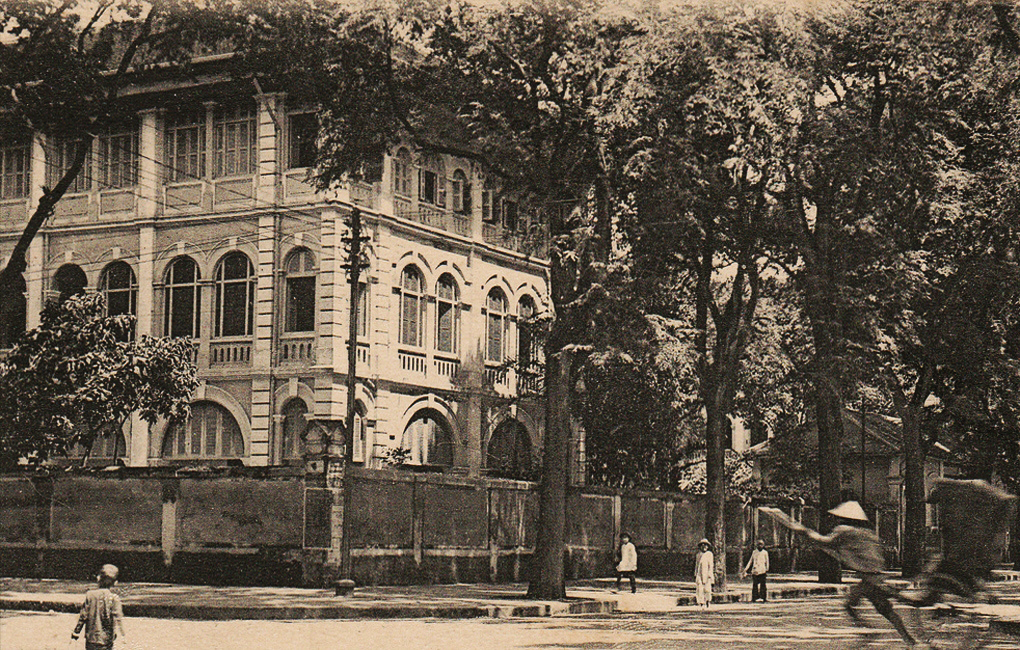

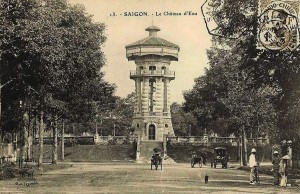

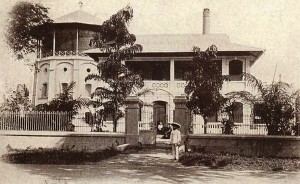

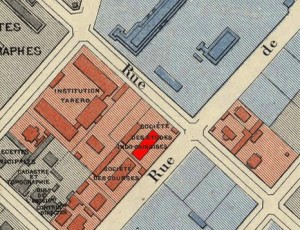

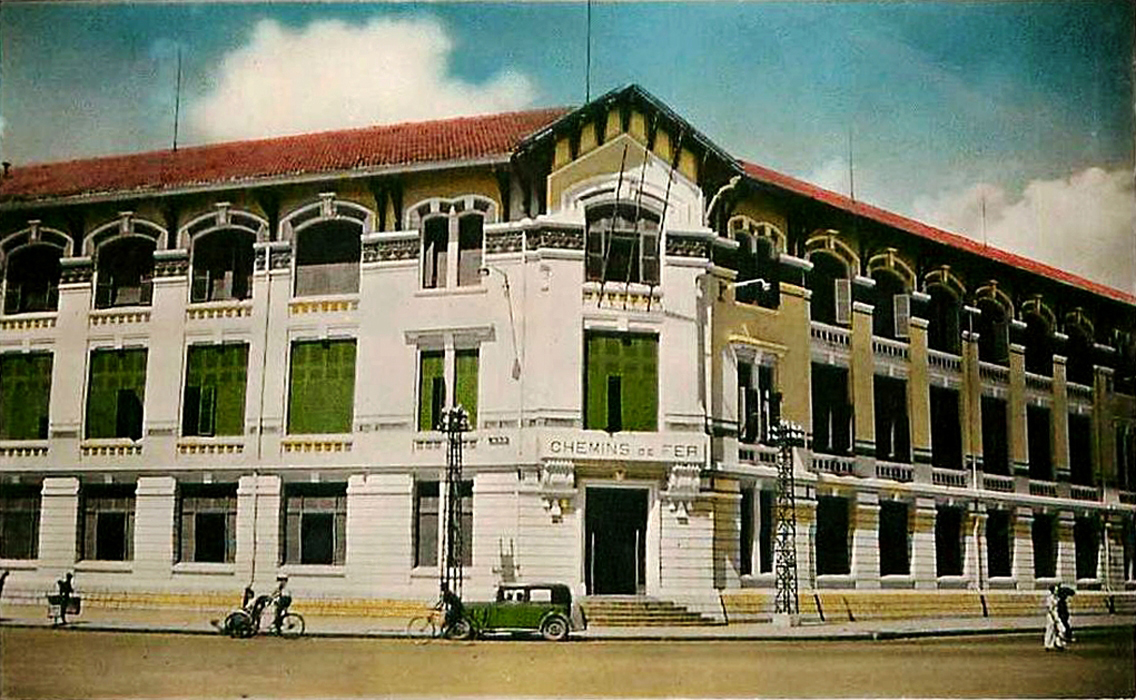

In the early 20th century, the villa which once stood on part of the Catinat Building site at 158 rue Catinat served a variety of functions. At various times it housed the offices of French companies such as the Société d’Oxygène et d’Acétylène d’Extrême-Orient and Pathé Cinéma. Between 1902 and 1905, the building and its garden even became the first home of the Cercle Sportif de Saïgon, offering a gymnasium, a fencing room and a small shooting gallery.

A Société urbaine foncière Indochinoise (SUFIC) plaque on the Lý Tự Trọng street side of the building

However, in 1925, both 158 rue Catinat and the adjacent plot on rue de Lagrandière were acquired by the wealthy Société urbaine foncière Indochinoise (Indochina Real Estate Company, SUFIC), which demolished the earlier structures to make way for the current building.

Being a five-storey block, the project involved the laying of deep foundations before construction got under way, and during the course of this work a fascinating discovery was made. The Bulletin de l’Agence générale des colonies of April 1926 reported this as follows:

“The discovery in Saigon of the remains of an ancient citadel

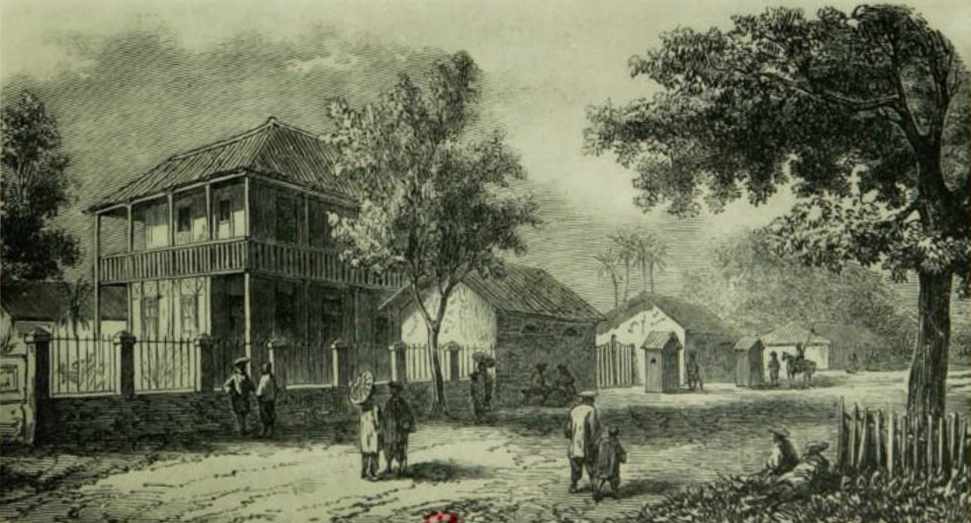

As we know, Saigon, capital of Cochinchine, was built on the ruins of the native town, which was completely destroyed by fire during the conquest.

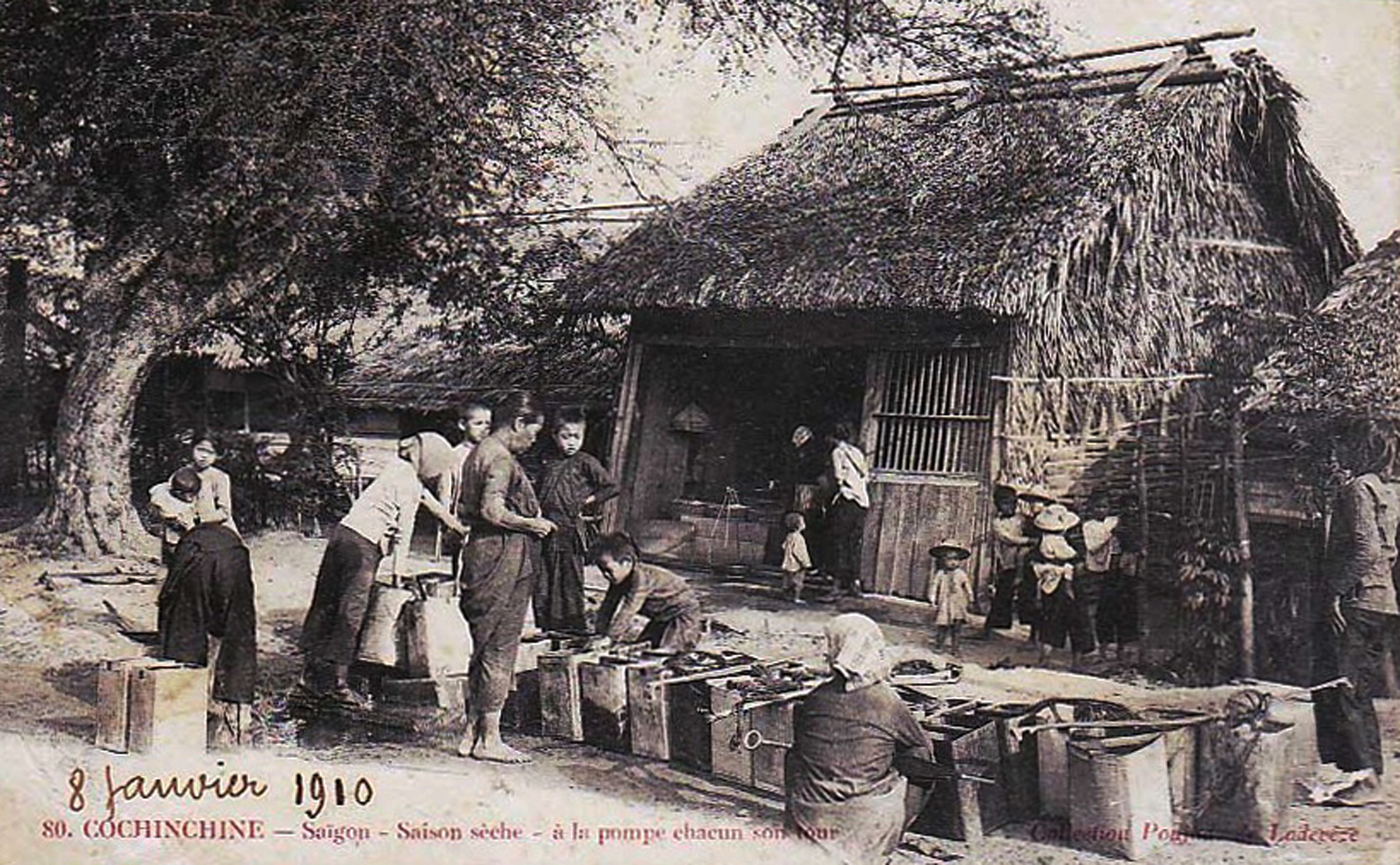

A colonial-era construction site in Saigon

However, our colleague from the journal l’Impartial reports that the city is, in fact, much older than we think. In this connection, he informs us of a chance discovery of vestiges of the ancient city: the remains of a building constructed in 1790.

This discovery was made at the junction of rue Catinat – the busiest and best shopping street in town – with rue de Lagrandière. For several weeks, this has been a vast construction site where, after demolishing the old buildings, workers have been digging the ground to prepare the foundations for a new one. However, having reached a certain depth, they encountered unexpected resistance. There they found strong walls made from enormous stones, with a very special appearance. Their existence at this depth surprised the engineers. Monsieur Jean Bouchot, the Government Archivist of Cochinchine, was immediately consulted. Thanks to early maps of the city, it did not take him long to identify the remains in question as remnants of the first citadel of Saigon, built in 1790. Monsieur Louis Finot, director of the École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) has confirmed this hypothesis.”

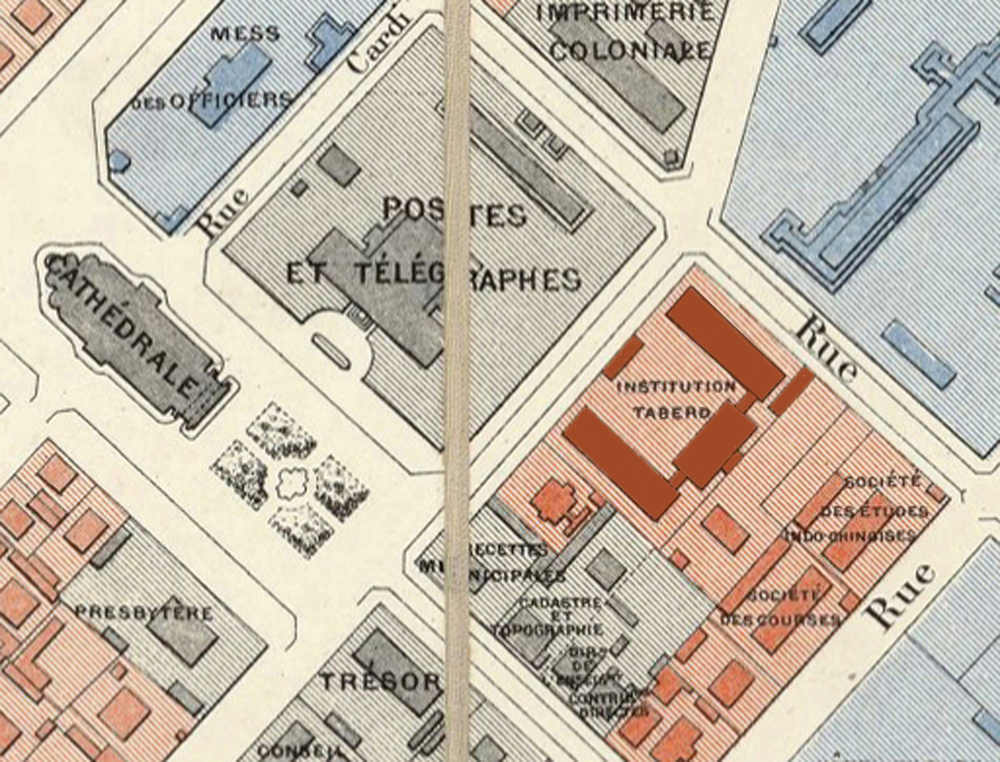

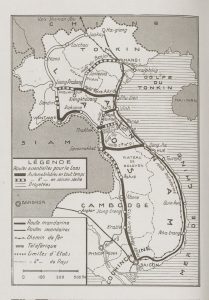

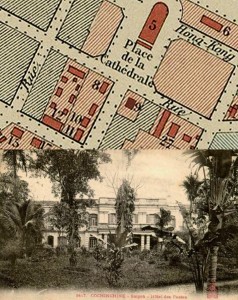

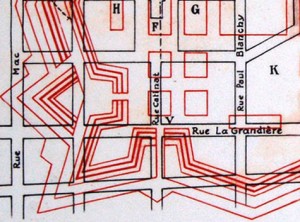

The rue Catinat/rue de Lagrandière junction as depicted on a colonial map which superimposes the lost 1790 citadel walls onto the French-era Saigon street layout

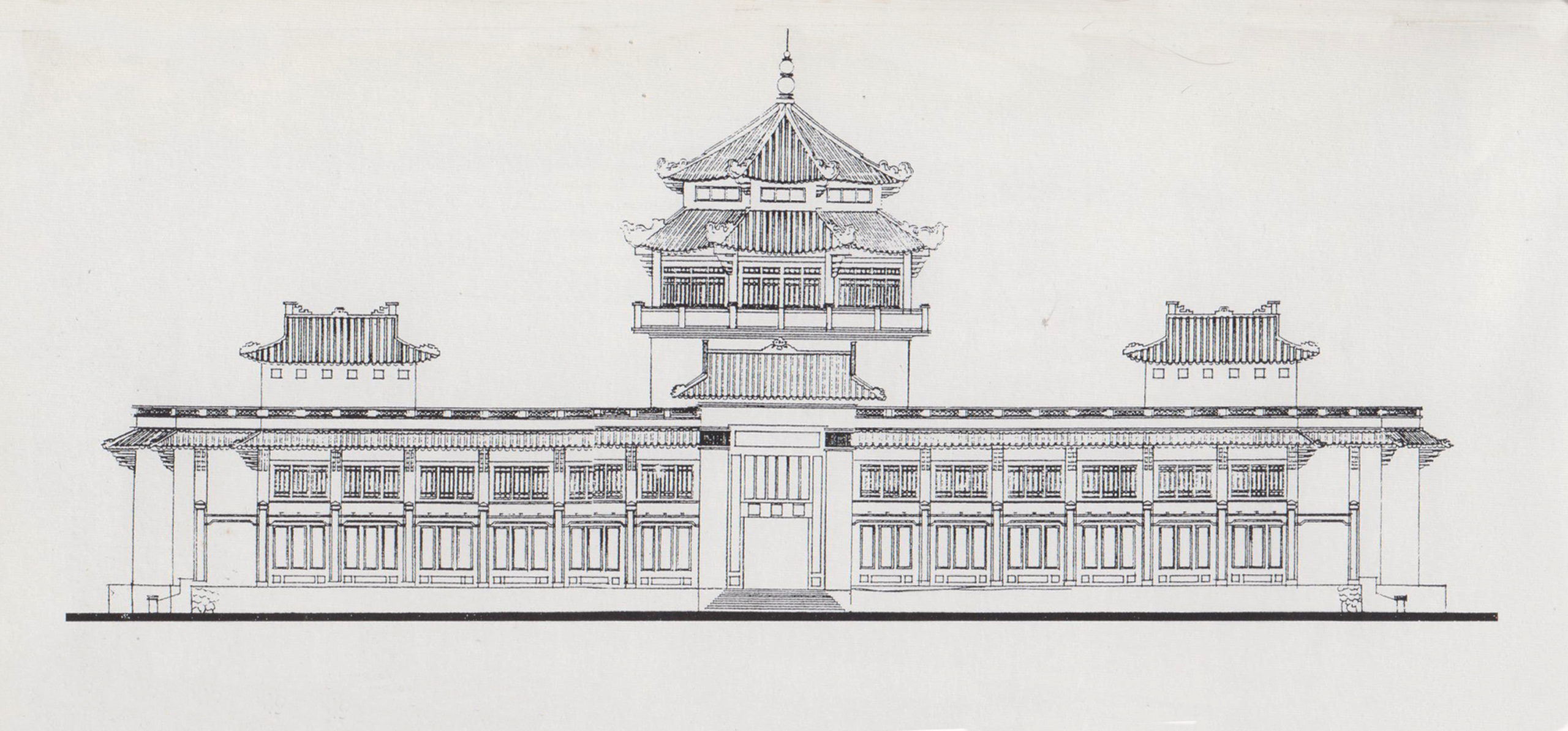

In fact, right down to 1835, the Càn Nguyên gate, main southern entrance to the 1790 Gia Định Citadel, stood on what is now Đồng Khởi street, between the junctions of Lý Tự Trọng and Lê Thánh Tôn. It is therefore most likely that the vestiges discovered in 1926 during construction of the Catinat Building were the bastions surrounding this gate.

Thereafter construction proceeded quickly and the Catinat Building with its main entrance at 26 rue de Lagrandière was inaugurated in early 1927. Plaques containing the names of its architects (the unnamed “architectes du Credit foncière de l’Indochine”) and its owner (SUFIC) were installed on the building’s walls.

Like the recently-demolished 213 rue Catinat, it was designed in art deco style as an up-market development targeted at a high-end clientele. In the 1930s and 1940s, its occupants included the Saigon offices of several rubber plantations – including the Société des Hévéas de Tây-Ninh, the Société Indochinoise des plantations Réunis de Mimot and the Plantation de Phuc-Ha.

A plaque crediting the unnamed “architectes du Credit foncière de l’Indochine” on the Đồng Khởi street side of the building (photo by Tom Hricko)

Other important tenants included the journals Revue Indo-chinoise illustrée and l’Impartial (which had broken the story about the citadel vestiges) and, from 1937, the city’s main tourist office, the Bureau officiel du tourisme Indochinois. In the 1940s, the building’s owner SUFIC and the Frigorifique company also took up residence here. From the outset, the ground floor corner was occupied mainly by restaurants and cafés.

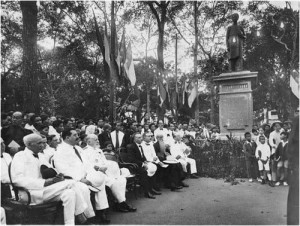

However, perhaps what really confirmed the status of the Catinat Building as one of the most desirable pieces of colonial real estate was the opening here in the early 1930s of the United States Consulate. This was the third home of the American diplomatic mission in Saigon after 4 rue Catinat (Đồng Khởi) and 25 rue Taberd (Nguyễn Du), and on 23 November 1941 it became the target of a devastating bomb attack – said to have been perpetrated by “Japanese gendarmerie” – which caused extensive damage to the Catinat Building. Just two weeks later, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and all US diplomats were expelled from Indochina. When the Americans returned in 1945, the US Consulate relocated again to 4 rue Guynemer (now Hồ Tùng Mậu street) before the opening of the first purpose-built US Embassy on boulevard de la Somme (Hàm Nghi boulevard) in 1950.

An iconic Hubert Van Es shot of the American helicopter evacuation of 29 April 1975 from the building next door

Intriguingly, it seems that while they were in residence, the Americans also acquired the building at number 22 next door, which remained US property right down to 1975.

By the 1960s it was known as the Pittman apartment building and housed the CIA station chief and several of his staff. On 29 April 1975, 22 Gia Long (Lý Tự Trọng) famously served as one of three main departure assembly points (the others being 192 Công Lý/Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa and 2 Phan Văn Đạt), from the roof of which American helicopter evacuations were made.

Since Reunification, the Catinat building has led a fairly uneventful life, its upper floors rented out as apartments and its prime ground floor retail spaces hosting in recent years an ever-changing array of bars, cafés and restaurants.

“Saigon, 24 November 1941: The State Department announced today that the US Consulate in Saigon, French Indochina, pictured above, was wrecked by a bomb last night. According to the Department’s announcement, no member of the staff was injured.” (US government press photo)

A LIFE magazine image of the Catinat Building in the 1950s

A modern view of the 22 Lý Tự Trọng rooftop taken from the Chi Lăng Park

Another external view of the Catinat Building today

Balcony ironwork in the Catinat Building (photo by Tom Hricko)

Window and handrail detail in the Catinat Building stairwell (photo by Tom Hricko)

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.