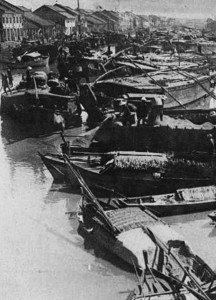

The Messageries maritimes quayside.

In mid 1888, wealthy French widow Louise Bourbonnaud set off alone on an extended voyage of discovery which took in India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Singapore, Cochinchina, China and Japan. She spent over a week in Saigon and her 1892 book Les Indes et l’Extrême Orient, impressions de voyage d’une parisienne provides us with a fascinating, if somewhat condescending, account of late 19th century colonial life. This is the second of a series of instalments from her book, translated into English.

To read part 1 of this serialisation click here.

Sunday 26 August 1888

Today is Sunday. At 7am it’s not yet daytime, but already my neighbours are facing their tasks: tailors, shoemakers and bleachers stitch, sew, wash and iron as if nothing had happened. It seems that these people have no respect for the Sabbath.

It’s only just sunrise. In the tropics, the sun rises late and the night comes early, almost without dawn and dusk: the days and nights are equal, and this remains surprising to Europeans who are accustomed to the days lengthening or decreasing, according to the season.

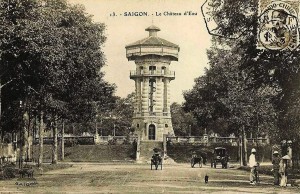

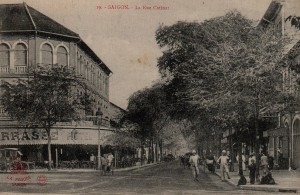

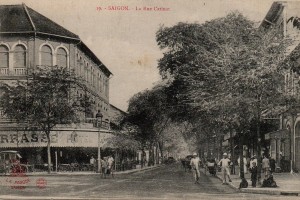

Rue Catinat, Saigon’s “boulevard des Italiens.”

The weather is gloomy, it ‘s still raining. It always rains!

But I didn’t come so far from France just to watch the rain falling from my hotel window. At 9am, I wrap myself in my waterproof, arm myself with a huge umbrella and walk bravely out onto rue Catinat.

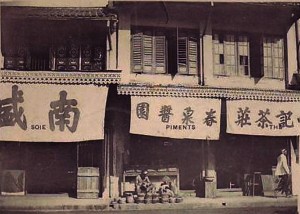

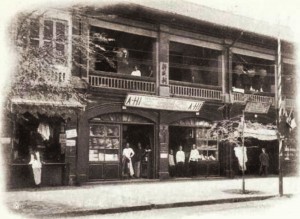

This beautiful road is the “boulevard des Italiens” of Saïgon; it begins at the quayside and ends at the Cathedral. It’s here that you will find all the beautiful shops and the beau monde, the City Hall, the Post Office, the Auction House, etc, etc.

In front of the Auction House, an Annamite man taps with a vengeance on a tom-tom. At least that’s a bit of local colour! I approach and I learn that this “tambourineux” of the Far East is announcing a sale being held this morning. I enter. Items of all kinds are being offered to the public, but most of them are European: mirrors, furniture, bedding, household utensils, various tools… alas, it seems that there is nothing worth bidding for.

I notice some pretty little model carriages drawn by cute little horses; but as I have a long way to go before returning to Paris, I have no intention of buying too many things. But wait! Here’s a pile of sheet music that would be right up my street! Just think, music purchased in Saigon! But this lot is to be auctioned later, says a police officer I ask for information. If I have time, I ‘ll come back.

The first Saigon Post Office on rue Catinat.

The Post Office [at this time still located on the site of the later Bót Catinat police station, now the Department of Culture, Sports and Tourism] is on my way. Time to see if my friends in France have not completely forgotten the poor exile.

No! they haven’t forgotten me. There are two letters addressed to me; in one of them, Miss B asks me jokingly if I’ve eaten swallows’ nests yet, a great delicacy, it seems.

No, miss, I haven’t tried it yet; I haven’t even heard it mentioned here, perhaps this dish is a less well known here than it is on the boulevard Montmartre. But I do not give up hope of tasting it one day or another, because when travelling you should never say never.

My kind correspondent writes that she envies me my lot and is somewhat jealous of me travelling the world. She wants to congratulate me on my courage and shudders at the thought that I have to endure the fatigues and dangers to which I am exposed.

Outside, I hear the Cathedral bells ringing; an elegant crowd throngs towards the holy place and I quickly join them to attend mass.

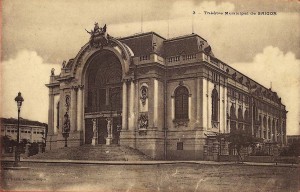

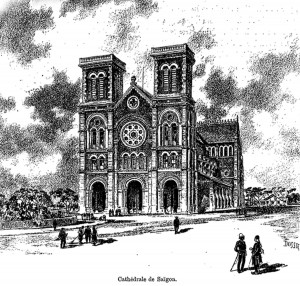

The Saigon Cathedral, inaugurated in 1880.

The Saigon Cathedral, which we can see from afar when first arriving in the capital of French Cochinchina, is built of pink brick which creates a curious effect. The building stands at the end of rue Catinat.

There are many ladies in full dress and many officers in uniform. The uniforms and the brightly coloured costumes cast a cheerful note on the proceedings – we are reminded that we are in the land of the sun. The bishop officiates, mitre and crosier; the ceremony is most impressive. Once mass is ended, I see in the crowd the English solicitor, former passenger on the Ava; but as I don’t much want his company right now, I hasten to join the congregation exiting the building before he notices me.

In any case, I must go to the sacristy to order a mass for the repose of my beloved late husband’s soul. The priest to whom I address this request asks me for a piastre and a half and gives me change in local sous. These are small round bronze coins, a bit larger than our two centimes pieces, and, like the Chinese sous, they are pierced in the middle with a square hole. They carry the words “Indo-Chine française,” and are, I believe, struck at the Paris Mint. They are called sapeks and it takes five to make a sou. He also gives me other, larger coins, weighing 10gm, called cents.

Leaving the cathedral, I decide to go back to the Auction House; but when I arrive, the sheet music that I noticed has already been sold. Too bad! At that moment, they are selling the miniature horses and carriages and I see a nice harness for the sum of 110 piastres.

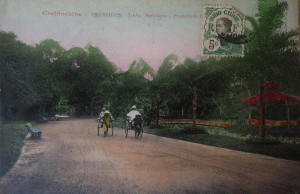

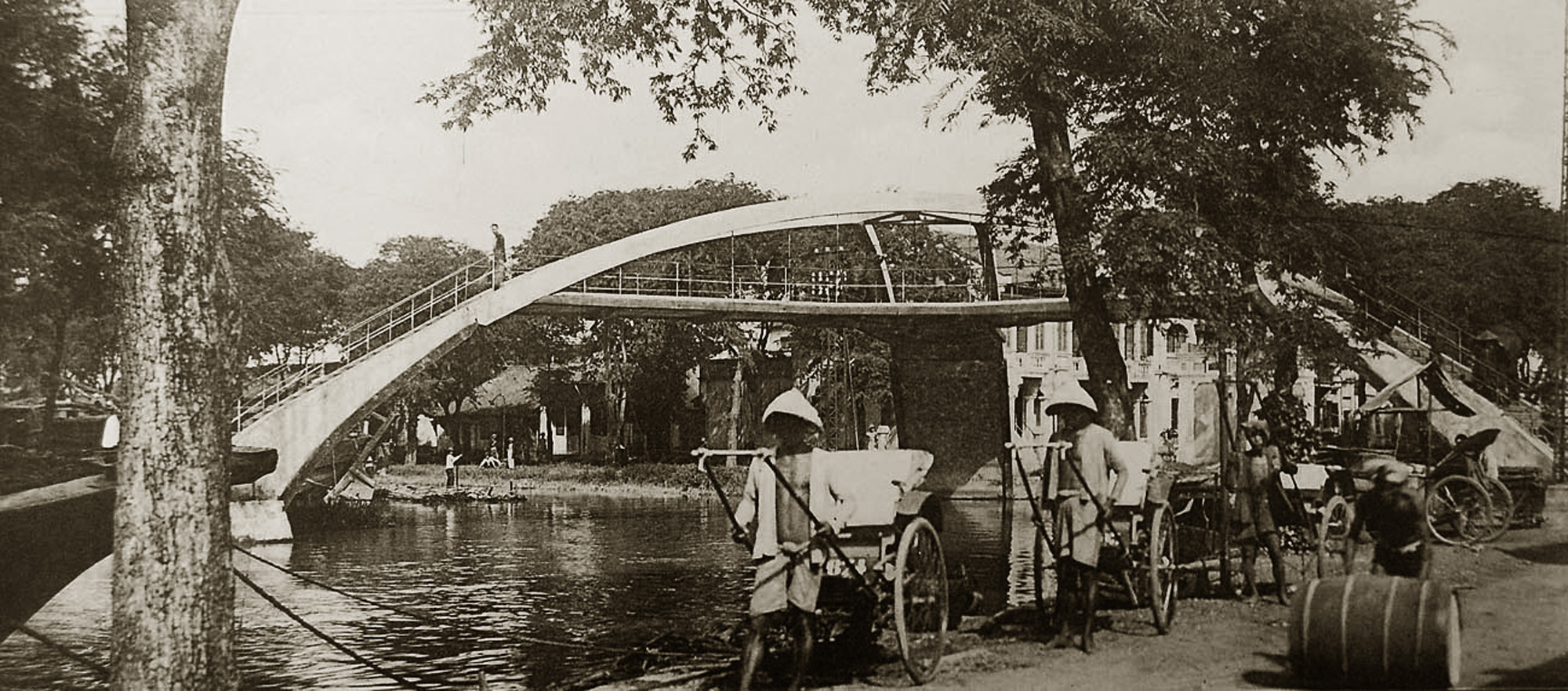

A malabar negotiates one of Saigon’s tree-lined boulevards.

What a pretty city Saïgon is! How graceful to see the houses hidden in the greenery and the wide boulevards lined with trees which cover the roads with beneficent shadow. The width of the streets is huge, the trees are so big, so tall and so thick that they cover everything. You must have visited this place to realise that there really is so much vegetation, because the traveller is always suspected of exaggeration.

The rain has stopped and the sun shines resplendently. Under the double shade of my umbrella and the thick foliage of the trees, with a prevailing wind, I feel a real sense of well-being; At every step I am amazed that there are so many people outdoors; many officers, some on foot, others driving themselves in carriages, and women dressed in the newest fashions brought by the last ship from France. I stand there, in the midst of the crowd, nailed to the spot in admiration, so amazing is the show. Ah! What a beautiful jewel of a colony France has here!

There are many reading rooms here, with signs indicating volumes for rent. But unfortunately, these French books are not read widely by the local people, as they seem to have no taste for the study of our language; it is rather our compatriots who assimilate the language of the country. However, there are honorable exceptions to this rule – like all rules – and many Annamite, Chinese and Malabar may be heard jabbering in the language of Voltaire and Victor Hugo.

I return to the hotel for lunch. The sun has gained strength and begins to create a stifling heat in the tree-lined avenues. In the dining room the punka fans have their work cut out for them.

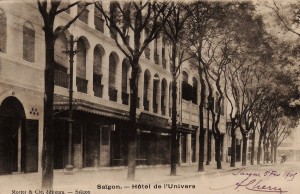

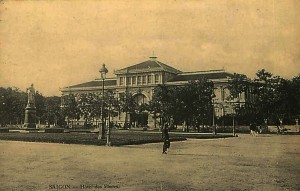

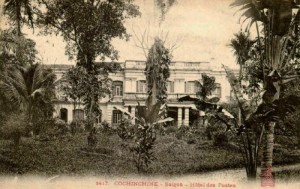

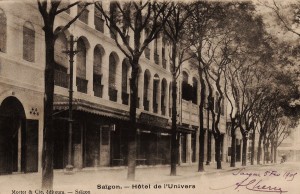

The Hôtel de l’Univers, where Louise Bourbonnaud stayed during her visit to Saigon.

I’m at the dining room table for barely a quarter of an hour when a gentleman presents himself to me on behalf of Mrs de X. I am invited to spend the rest of day and have dinner tonight with my amiable companions. This attention from people so highly placed in the official world of the colony touches me deeply, but I still want to keep my freedom today, so I tell the messenger that I cannot accept the gracious invitation that has been made until tomorrow.

From that moment, I realise that the invitation has improved my standing at the hotel; everyone redoubles their kindness towards me when they know I have such beautiful acquaintances among the authorities of the country. Mr de X. enjoys a magnificent position in the government: a high salary, a princely house furnished with all the refinements of comfort; senior officials, moreover, are allowed two servants; others below them must pay out of their own pocket.

I wait for the great heat to pass and at 4pm I take a drive in a carriage. A random trip, because I have no guide and the driver does not understand a word of French and cannot give me any explanation. He looks at me, rolling his large white eyes with a dazed expression and utters exclamations which naturally I do not understand either. I decide to let him drive me at will; after all, there are interesting things to be seen everywhere for a newcomer like me.

We first do a tour into the countryside, which is charming and animated. I pass through a village where I notice a beautiful peacock.

An elephant at the Saigon Botanical and Zoological Gardens.

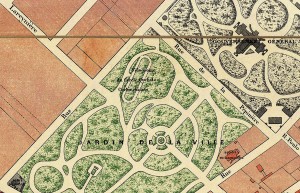

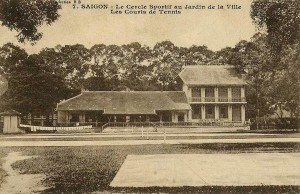

Then my driver takes me to the Jardin des Plantes [the Saigon Botanical and Zoological Gardens]. A good hour, at least! Here is a place that really deserves to be seen!

Firstly, it has elephants, and this is the first time I have seen any since my departure. I am pleased finally to contemplate these good creatures, which are as intelligent as strange and seem like vestiges of a bygone age. There are also tigers here, and beasts of every kind, as well as beautiful tropical plant collections. The animals and plants are all in their country of origin, in a climate that suits them, so they have an appearance of strength, health and vigour which we never see in the zoos back home amidst the cold, snow and fog.

The Annamites are, it seems, very fond of the flesh of the crocodile, an animal which abounds in some arroyos around these parts; but instead of hunting the animals, they prefer to raise and fatten them in specially-constructed pits, where, by using a noose, they can catch the overweight game easily and bring it straight to the pot.

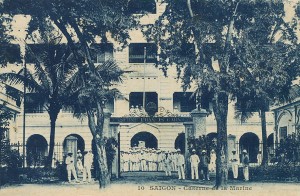

Here I am back on the quayside, where several warships are moored, amongst others the Loire. What a beautiful ship! I pass the Marine Arsenal, travelling along the rue de la Citadelle, a huge avenue which stretches far out of sight. This area has artillery barracks, supply stores, the Cercle des officiers – it seems that I’m in military terrain!

The French naval barracks on the Saigon riverfront.

In Saigon, like everywhere else of the same latitude, the shops are closed from 11am to 2pm, and only reopen after the owners have had their midday nap. It is very dangerous to walk in the hot sun at those hours of the day and the slightest carelessness can cost you dearly. But don’t believe that all local artisans, tailors or shoemakers stop working at this time. On several occasions when I found shops closed, I could still hear the noise of the sewing machine continuing inside.

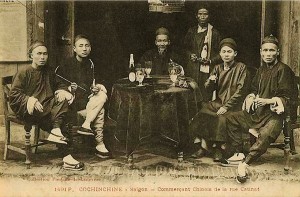

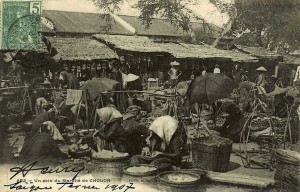

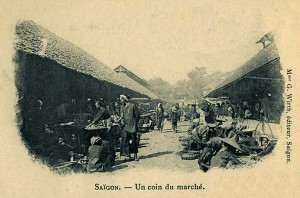

At about 4pm, everyone comes out onto their doorstep and begins to eat. I observe them and am surprised by the frugality of the menu: nothing but rice! These people, of course, eat to live and not live to eat. They don’t use plates, but rather a bowl which they bring towards their mouth with every bite, while, in the right hand, they manipulate their chopsticks with extraordinary dexterity.

Rice is the staple food of the Annamite and the condition of the crop is the subject of many conversations. Everyone rejoices when the rain falls in torrents, because it’s a sign that the harvest will be plentiful; because the rice is grown literally in the water, drought years are years of famine. Since the French occupation, those horrible famines that once devastated entire countries have become rarer and much less deadly. Thanks to the speed of modern communications, if there is a shortage of rice in one place, we can, without too much expense, go and buy elsewhere, where the harvest has yielded good results.

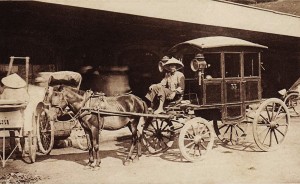

Carriages await the arrival of a ship in colonial Saigon.

In the streets, I meet many brave sailors who are enjoying their Sunday leave by coming ashore to stretch their legs a bit. They go here and there, legs apart, looking amazed to find their feet on ground that does not rock from side to side, seeking drinking dens where they can spend their pay. They are spoiled for choice, as drinking places are certainly not lacking in Saigon! And when the sailor reboards his ship after a day’s leave, you can be sure that he will no longer be as neat and tidy as he was when he landed in the morning; so he had better beware the coxswain!

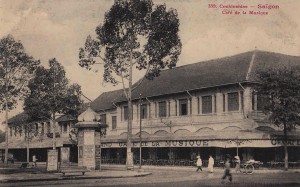

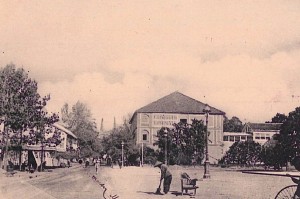

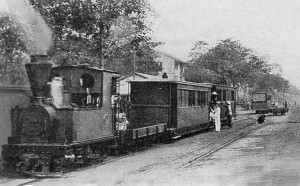

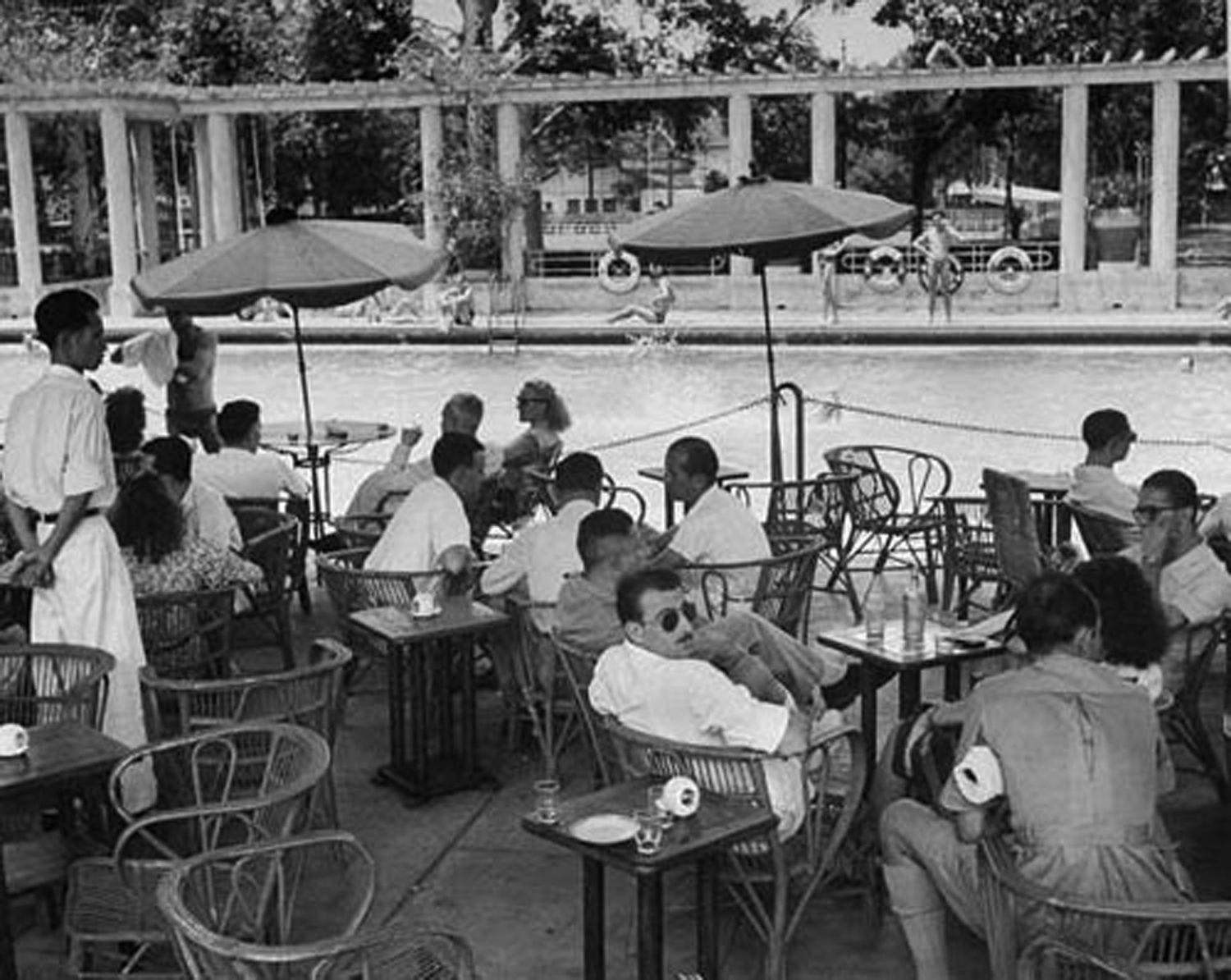

Music hour has arrived and no-one in Saigon’s belle société fails to attend “la musique.” It is mandatory!

The military concert takes place on the magnificent square opposite the Jardin des Plantes. As it only begins at 6pm, I first take a walk along the tree-lined avenues, where who should I bump into but… the rude Prussian who blew pipe smoke in my face on the Ava! I turn away in disgust from this character, who pretends not to recognise me.

Gradually, the world makes its way to the square, some people on foot, some on horseback, and others by carriage. Fashionable dresses, shiny uniforms, splendid carriages, coachmen and footmen, it’s like being at the lake in the Bois de Boulogne! The carriages fall into two files. Their occupants get out, greet each other. The gentlemen, wearing black or light cloth suits decorated with flower buttonholes and polished shoes, carry a cane or a whip in their hands. Some stylishly-dressed military officers arrive leading their own poney-chaise, carelessly throwing the reins to their servants as they begin to meet and greet.

French colons dressed in the latest fashions.

The ladies are dressed in the latest fashions; some outfits are quite garish, but here the world is naturally a bit confused. Blue, pink, green, purple and cream silk dresses abound, all light shades shining in the sunlight. It’s quite hard to believe that we are 2,000 leagues from the place de l’Opéra, even if the beautiful tropical greenery that frames this tableau is a constant reminder to the viewer of reality.

Two Annamite woman arrive in an open carriage. They are dressed in pink silk skirts and green silk blouses and their hair is kept in place by enormous tortoiseshell combs and brooches garnished with large pearls. Their hairstyles look a bit like those of the Japanese. On their feet they coquettishly wear small, lightweight shoes with pointed toes and open heels in green, pink and purple velvet, decorated with gold or silver embroidery. They are very pretty and, it seems, very rich.

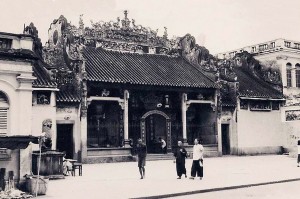

The senior local mandarins are also here, listening seriously to the music of Auber, Rossini or Herold, which I’m afraid they may not understand much, because their ideas of musical harmony are different from ours.

The Annamite men here wear their hair in a little bun in the manner of the Spanish bullfighter. They are dressed in similar outfits to the Annamite women, so it is very difficult, at first, to distinguish one from the other.

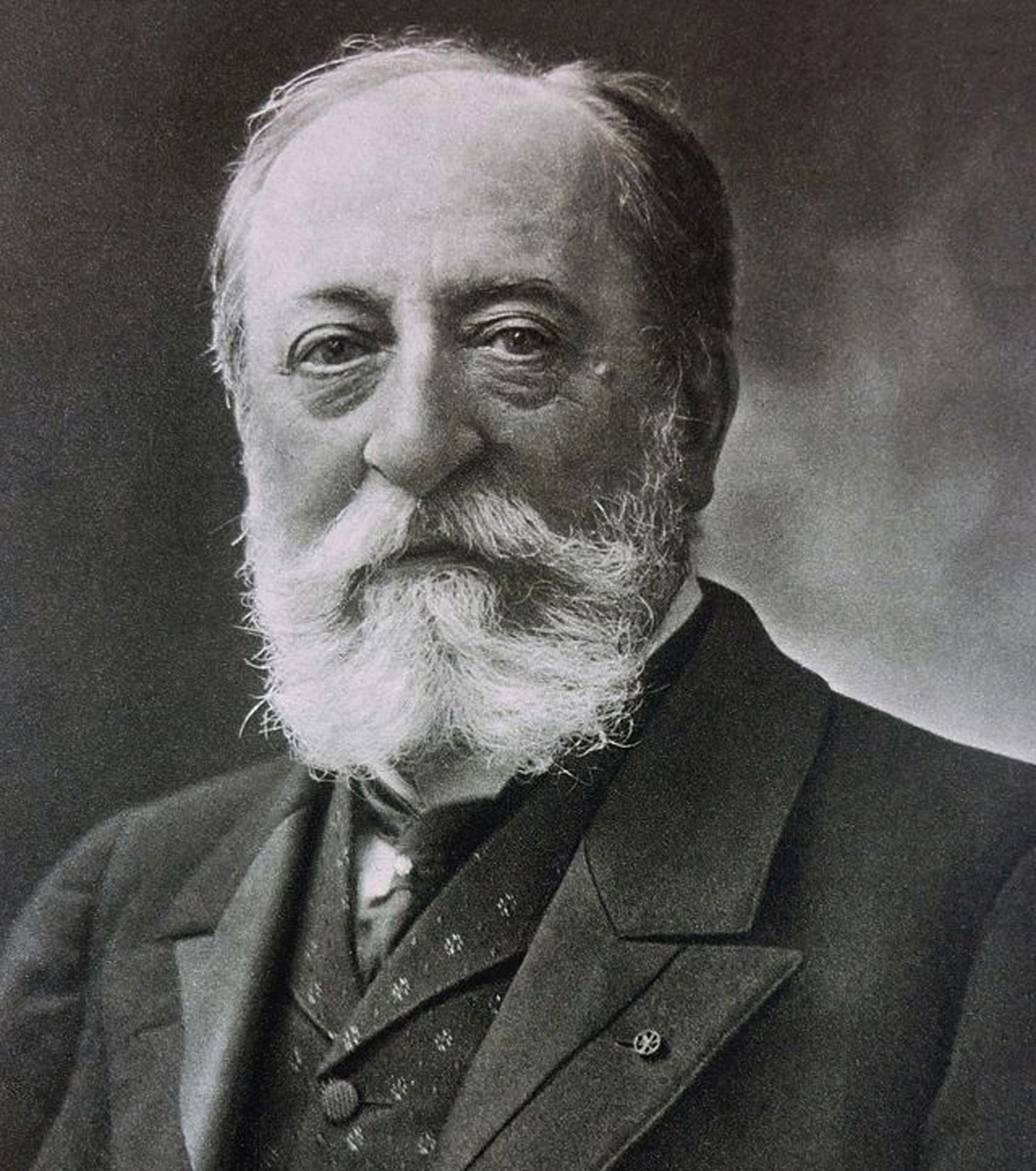

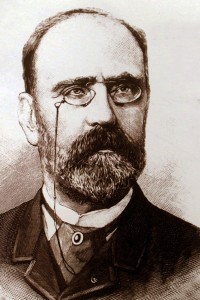

Étienne Richaud, who, after being appointed Résident général in Annam and Tonkin, succeeded Ernest Constans in April 1888 to become the second Governor General of Indochina.

All of a sudden, the crowd gathers respectfully around a large landau, on the high platform of which stand a coachman and a footman dressed all in white, with large gold buttons on their chests and enormous white helmets decorated with a tricolor cockade and a ribbon in the French national colours.

In the landau are two people: Mr Richaud, currently Résident-Général of the colony, and Mrs Richaud. The Résident-Général is a very handsome man, tall, well-cut, a colossus! His charming wife distributes left and right gracious greetings and waves of her hat. As this officer is the highest incarnation of French authority, all of the French and Annamite administrators bow respectfully to “captain six-gallons!”

I must explain here that the Annamite regards every European dressed for an official civilian or military function as a “captain” and grades his importance by the number of “gallons.” In this way, the simple sub-lieutenant is promoted, in the familiar language of the local people, to “captain one-gallon.” The lieutenant, who is entitled to a more respectful salute, is “captain-two-gallons.” As for a true captain, he is naturally “three-gallons.” The colonel and lieutenant-colonel lose out, but although they are designated by a title below that which is rightfully theirs, they nevertheless retain their respective rank in this improvised and exotic hierarchy, as “captain four-gallons” and captain “five-gallons.”

So much for the military, and so far nothing difficult in the designation of grades, since each of them corresponds with the number of gallons. But for civilians? Well, the Annamite also classifies a European civilian official who has under him a number of staff according to his importance, as two, three, four or five gallons!

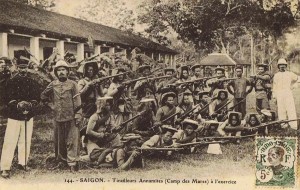

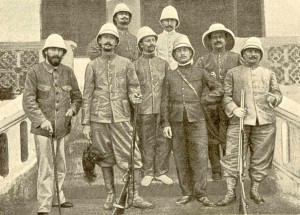

French military colons in the late 19th century.

And over the army of officers and officials, which includes most French colons including traders and industrialists, above all that world soars the Governor, the Résident Général, this unique “captain six-gallons” to whom we now bow low!

I meet the two youngest sons of Mr de X in a Victoria carriage drawn by two horses; driven by two coachmen dressed in blue cloth jackets and white helmets. This is the little outfit of army coachmen; an officer of a certain rank is entitled to this crew.

Ah! It seems that these people lead life to the full! But just because they have a lot of money, it doesn’t mean to say that they benefit from it, because in reality they are obliged to spend vast sums. Here in the colonies, they must give a lot of parties, dinners and balls; it’s all about who can eclipse his or her neighbour – especially a female neighbour! Fashions are dictated by the Louvre, Bon-Marché and Printemps; if you are rich, you employ some great couturier from the avenue de l’Opéra or the rue de la Paix, and every mail brings large quantities of dresses, lace, hats, etc. These ladies wear their dresses perhaps just three times and then give them to their maids, because they don’t want – for anything in the world – to look like they are saving money!

Then there’s the carriages – in the daytime they use a covered carriage, but if they are out in the evening it’s also necessary to have an open carriage. And of course, they never, ever walk – someone would notice!

A malabar waits for passengers

At that rate, we can see how the biggest salary packages are hardly enough and that it does not take long to be unable to make ends meet.

I haven’t been in Saigon very long and yet you’d easily believe that I’m already well known, because I’m greeted at every moment: they are passengers from the Ava, former companions, who came, like me, to the select rendezvous of “la musique.” I see, amongst all the others, the Agent des postes, lounging in a carriage alongside an army commander.

I return to the hotel to find a messenger from Mrs X, who has come to find me for the second time. The friendly lady, it seems, is furious with me; she waited for me all day. I apologise as best I can. Today is Sunday, I was afraid to disturb my new friends; in brief, I promise to visit them tomorrow, after the midday nap. Not that I intend to take a nap, oh no! I won’t waste my time sleeping during the daytime, but I cannot decently make a visit at the hour when everyone retires to the coolest room of their house to rest until the heat of the day has passed.

I dine quietly and take ice-cream after my dessert, I ask the manager of the hotel to come and keep me company for a moment.

Afterwards, I go back to my room, put my notes in order and record my impressions of the day. As I never stop, I keep going and coming, I have seen a great many things, and if I don’t note them down as I go along, I run great risk of forgetting them.

That done, I take a well earned rest.

To read part 3 of this serialisation click here

To read part 4 of this serialisation click here

To read part 5 of this serialisation click here

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.