The title page of The mission to Siam, and Hué, the capital of Cochin China, in the years 1821-2. From the journal of the late George Finlayson … With a memoir of the author, by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, F.R.S (1826)

In 1821-1822, Lord Hastings, the Governor-General of India, sent a British trade mission to Siam and Cochinchina led by John Crawfurd. Scottish naturalist George Finlayson (1790–1823) accompanied the mission, and his journal, published posthumously in 1826 as The mission to Siam, and Hué, the capital of Cochin China in the years 1821-2, provides some fascinating observations about Gia Định under the governance of Viceroy Lê Văn Duyệt.

August 28th-29th: At 6pm we left our ship, a salute being fired on the occasion, and the ship’s crew giving us three cheers. The Annamite [Vietnamese] barge selected for our transportation was comfortably as well as elegantly finished. Continuing to row all night, notwithstanding that it rained incessantly, by daylight we were but a short way from Saigon, and reached it at 9am. The boat was furnished with a suitable number of officers. The discipline of the men rested chiefly with the second, whose rank may have been equal to that of sergeant or corporal. He cheered the rowers by the repetition of a few wild cries, which could scarce deserve the name of a song, beating time to the stroke of the oar by means of two short sticks of hard wood. The discipline of these soldiers is severe, for even this petty officer had the power of inflicting several hundred lashes of the rattan stick for the slightest offence. The rattan stick was kept in constant exercise, as we found on our arrival at the town.

The Crawfurd mission travelled in the John Adam, a ship similar to the one depicted in William Anderson’s painting Shipping on the Thames off Deptford, oil on panel, National Maritime Museum, London

The river of Saigon is about the size of that of Siam, but appears to carry a greater body of water. It is navigable to ships of all sizes. It is less tortuous than most rivers, and its waters are less turbid. Its banks are mostly covered with mangrove. We found among them a very elegant species of rhizophora [a genus of tropical mangrove], but observed no cultivation until we were within 20 or 30 miles of the town. The number of boats that we passed was but infrequent.

As we approached the town, we were surprised to find it of such extent. It is built chiefly on the right bank of the river. We had already passed a distance of several miles and were still in the midst of it. The houses are large, very wide, and for the climate, very comfortable. The roofs are tiled, and supported on handsome large pillars of a heavy, durable black wood, called sao. The walls are formed of mud, enclosed in frames of bamboo and plastered. The floor is boarded, and elevated several feet from the ground. The houses are placed close to each other, disposed in straight lines, along spacious and well-aired streets, or along the banks of canals. The plan of the streets is superior to that of many European capitals.

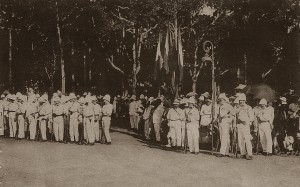

We were conducted to a house that had been prepared to receive us. Several thousands of the people, besides a numerous guard of soldiers armed with lances, were collected to receive us. The crowd conducted themselves with a degree of propriety, order, decency, and respect, that was alike pleasing as it was novel to us. All of them were dressed, and the greater number in a very comfortable manner. They all appeared to us remarkably small; the rotundity of their face and liveliness of their features were particularly striking. The mandarin who had accompanied us on the barge conducted us to our house and placed us in the hall, seated upon benches covered with mats, opposite each other. A number of people were in attendance to take up our baggage, and to make such arrangements in our quarters as we should deem necessary.

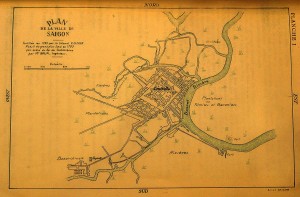

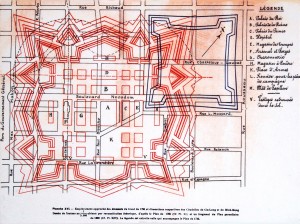

This 1793 map of Saigon shows the location of the 1790 Gia Định Citadel

The house was one of the best in the town. It was difficult to say whether it partook more of a temple, or of a court of justice. In every house, in every building, whether public or private, even in the slightest temporary shed, is placed something to remind you of religion, or, to speak more accurately, of the superstitious disposition of the people; and as the emblems of this nature have for the most part a brilliant appearance, they produce an effect as agreeable to the first glance as it is striking. At one end of this hall was an altar, dedicated to Fo, ornamented with various emblematical figures, and hung round with inscriptions. It was easy to perceive that affairs of state and of religion were inseparable here. Each partakes of the same gold and the same varnish.

Immediately behind the hall were placed our private apartments. A crowd of soldiers at all times filled the court and the ante-room, and a guard was placed in attendance at the gate and wicket.

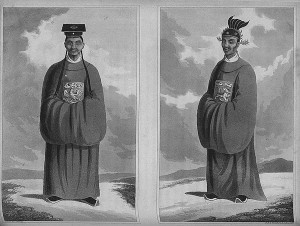

At noon, two mandarins of justice came to confer with the Agent of the Governor General. We received them upon our benches, immediately in front of the altar of Fo. They were men who had passed the age of 50, short in stature, of easy and affable manners. They were dressed in black turbans, and black robes of silk. They commenced the conversation by making enquiries about our accommodation; then they turned to the objects of the mission, asking how long it had been since we had left Bengal; whether the letter for the King of Cochin China was from the King of England, or from the Governor General of India; what were the precise objectives of the mission; whether we had orders to visit Saigon, or the contrary; and if we had been at the court of Siam. To all of these queries, the answers were so plain and so candid that it seemed impossible that they could either misunderstand or misrepresent them. However, on one or two subjects, they showed the greatest anxiety. We were earnestly and repeatedly asked if we came into their country with friendly or hostile intentions. This subject was urged with so much earnestness that it was impossible not to forgive their fears, though groundless, and to participate in feelings which appeared to proceed solely from the love they bore for their country.

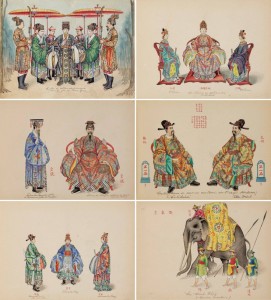

French-era illustrations of Nguyễn dynasty court scenes

They now requested that the letter to the King of Cochin China should be sent for, in order that the Viceroy of Saigon might be enabled to forward a translation to court, together with a full report upon the subject of our visit, but it was thought improper to comply with this request for the present. They seemed quite satisfied with the answers that were given, and continued the interview for nearly six hours, conversing almost all the while on matters of business. Before their departure, they ordered provisions for our use; and soon after, a live pig, ducks, fowls, eggs, sugar, plantains and rice were delivered to us.

In the evening, we were visited by Monsieur Diard, a lively and well-educated Frenchman of the medical profession, who had been led into these countries by his desire to prosecute subjects of natural history. He had already traversed most of the Indian islands, in which he had made numerous and valuable zoological discoveries, the subject which had principally attracted his attention. Already he had discovered four or five new species of primate, and as many species of the genus sciurus [squirrel]. In Java, he discovered that the large deer of that place was a species altogether unknown to naturalists. He thought that he had discovered a fourth species of rhinoceros, and was satisfied that the Sumatran species is a distinct one. The number of new species of birds which he has discovered is very considerable.

Monsieur Diard is evidently a man of great enterprise and acuteness, and admirably qualified for the arduous pursuit in which he is engaged. He is fond of adventure and ingenious in overcoming obstacles. From him we may expect a full account of the zoology of these countries. He has wisely assumed the costume, and adopted the manners of the people among whom he resides. If there be anything amiss in the character of Diard, it is (and it is with hesitation and doubt that I make this remark), perhaps, a disposition to over-rate the number, extent, and value of his discoveries; and perhaps too, an ardour of zeal which may be apt to lead one beyond the precise limits of accurate observation. He has been about a year in Cochin China, and four months at this place. It is with the greatest difficulty that he can obtain from the government permission to visit any part of the interior. He had but very few objects of natural history, in consequence, to show us.

August 30th: On going out in the morning, the guard placed at the gate seemed doubtful whether he ought to let me pass. On my approach, however, he drew back respectfully; but he strenuously objected to allow any of our people to pass the gate, until, seeing me wait for the painter, he permitted him to accompany me. An early visit to the market places served to confirm the observations I have already made respecting the manners of the people.

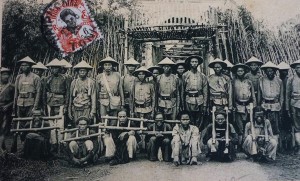

A royal mandarin being carried in procession

The Cochin Chinese cannot, I think, be considered as a handsome people in any way, yet, among the females, there are many that are even handsome, as well as remarkably fair, and their manners are engaging, without possessing any of that looseness of character which, according to the relation of French travellers, prevails amongst this people. The conduct of both sexes is agreeable to the strictest decorum. Chastity, in which they have been accused to be wanting, would appear to be observed, in the married state, with as much strictness as amongst neighbours, or any other Asiatic nation. The breach of it is held criminal, disgraceful, and liable to punishment. It is not so, however, with regard to young and unmarried females. Here the utmost latitude is allowed, and, for a trifling pecuniary consideration, the father will deliver up his daughter to the embraces of the stranger or visitor. No disgrace, no stigma, attaches to the character of the female, nor does this sort of connexion subsequently prevent her from procuring a suitable husband.

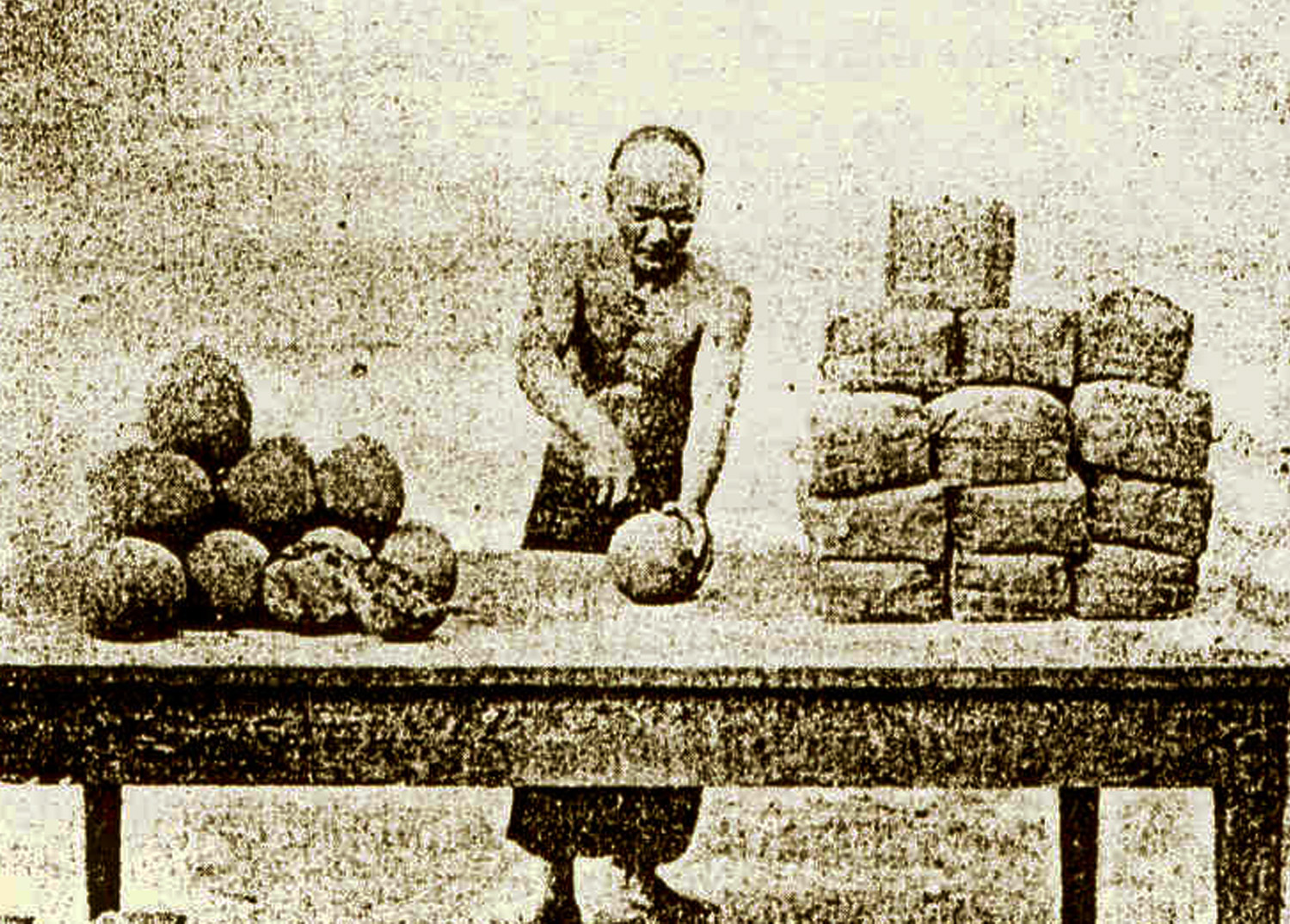

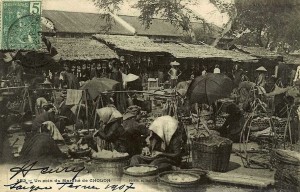

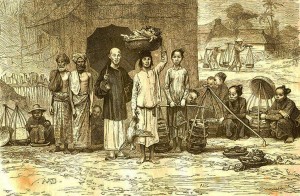

Such commodities as are used by the natives are to be found in great abundance in every bazaar. No country, perhaps, produces more betel or areca-nut than this. Betel-leaf less abundantly; fish, salted and fresh; rice, sweet potatoes of excellent quality, Indian corn, the young shoots of the bamboo, prepared by boiling. Rice, in the germinating state, coarse sugar, plantains, oranges, pomelos, custard apples, pomegranates and arid tobacco were to be had in the greatest quantity. Pork is sold in every bazaar, and poultry of an excellent description is very cheap. Alligator’s flesh is held in great esteem, and our Chinese interpreter stated that dog’s flesh is also sold here.

The shops are of convenient size, in which the wares are disposed to the best advantage. One circumstance it is impossible to overlook, as it exhibits a marked difference of taste and manners in this people from that of the nations of India. Articles of European manufacture have, amongst the latter, in many instances, usurped the use of their own; and you can scarce name any thing of European manufacture which is not to be had in the bazaars. Here, with the sole exception of three or four case bottles of coarse glass, there was no article whatsoever to be found that bore the least resemblance to anything European. A different standard of taste prevails. A piece of cotton cloth was scarce to be seen. Crepes, satins and silks are alone in use, the greater number of them the manufacture of China or of Tonquin, there being, in fact, little or no manufacturing industry here.

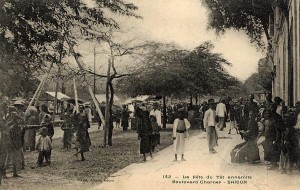

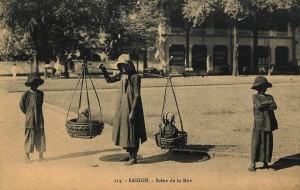

An engraving of a Saigon market scene

The articles which they themselves had made were not numerous. I may specify the following: handsome and coarse mats, matting for the sails of boats and junks, coarse baskets, gilt and varnished boxes, umbrellas, handsome silk purses, in universal use, and carried both by men and women; iron nails, and a rude species of scissors.

Everything else was imported from the surrounding countries. In exchange, their territory affords rice in abundance, cardamoms, pepper, sugar, ivory, betel, etc.

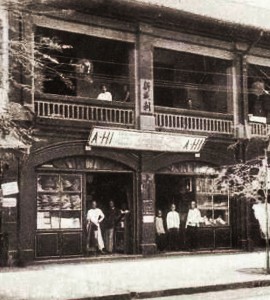

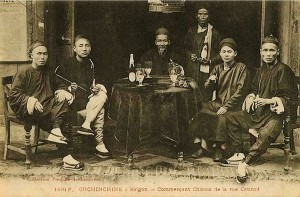

There are a few wealthy Chinese who carry on an extensive trade here; the bulk of the people are miserably poor, and but few amongst them are in a condition to trade but upon the most limited scale.

Few of the shops in the bazaars appear to contain goods of greater value than might be purchased for 40 or 60 dollars, and the greater number are not worth half that sum.

It is difficult to conceive that a population so extensive can exist together in this form, with trade on so small a scale.

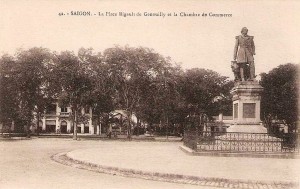

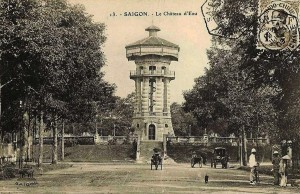

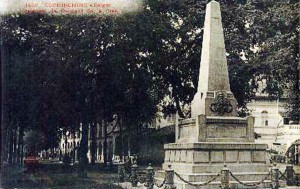

There are, in fact, two cities here, each of them as large as the capital of Siam. That more recently built is called Bingeh [Bến Nghé, later Saigon]; the other, situated at a distance of a mile or two, is called Saigon [Tai Ngon or Dī Àn 堤岸, literally “embankment,” the name used from the 1780s until the 1860s to describe Chợ Lớn].

The former is contiguous to a fortress which has been constructed of late years on the principles of European fortification. It is furnished with a regular glacis, a wet ditch and a high rampart, and commands the surrounding country. It is of square form, and each side is about half a mile in extent. It is in an unfinished state, no embrasures being made, nor cannon mounted on the rampart. The zig-zag is very short, the passage into the gate straight; the gates are handsome and ornamented in the Chinese style. We could not procure any information respecting the population of the two cities.

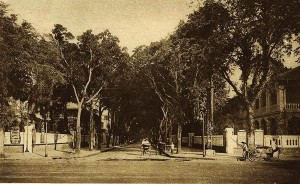

This late 19th century map drawn shows the location of the 1790 and 1835 citadels in relation to the colonial street plan of Saigon

A mandarin of higher rank, together with the two we saw yesterday, came to transact business with the Agent of the Governor General; a protracted conversation, in all respects similar to that which had taken place yesterday, was commenced by him. He insisted that the letter, as well as Mr Crawfurd’s credentials, should be sent for; this point was acceded to, and a boat was immediately despatched to the ship for the letter to the King of Cochin China. The mandarins continued with us till a late hour in the evening.

August 31st: At 11am the letter arrived, and in the course of an hour thereafter, the mandarins who had visited us first came to ascertain its authenticity and to report upon its contents. It was late in the evening before they could be made to understand the subject of it, or the nature of the Governor General’s proposals respecting commerce. An English copy of the letter, and translations in Portuguese and Chinese, were furnished to them. Monsieur Diard was present at, and took a part in, the conferences that were held with the mandarins.

September 1st: It would appear that the Viceroy had no objections to offer upon the subject of the documents which had been furnished yesterday; a mandarin now returned for copies of them, stating that those which had first been furnished were to be despatched immediately to Court. As soon as these had been furnished, we set out in a boat with Monsieur Diard to visit Saigon [Chợ Lớn].

The distance of this town from the Citadel is about three miles, but there are houses along the banks of the river the greater part of the way. The paucity of junks and coasting vessels in the river was accounted for by the lateness of the season. The number of boats that were passing and repassing was, however, very considerable. The country here presented the appearance of extreme fertility; the banks were covered with areca and coconut trees, plantains, jackfruit and other fruit trees.

This 1815 map shows the “Chợ Saigon” or Saigon Market in what is now Chợ Lớn – the name comes from Tai Ngon or Dī Àn 堤岸, literally “embankment,” which was used from the 1780s until the 1860s to describe Chợ Lớn, but was later appropriated by the French to rename Bến Nghé

Numerous navigable canals intersect the country in every direction, offering every facility for the increase of commercial industry. Here, as in Siam, the more laborious occupations are often performed by women, and the boats upon the river are in general rowed by them. A practice, as ungallant as it is unjust, prevails both here and in Siam; that of making females only to pay for being ferried across rivers, the men always passing free. The reason alleged for this practice is that the men are all supposed to be employed on the King’s service. It is lamentable to observe how large a proportion of the men in this country are employed in occupations that are totally unproductive to the state, as well as subversive of national industry. Every petty mandarin is attended by a multitude of persons.

The town of Saigon [Chợ Lớn] is built upon a considerable branch of the great river, and upon the banks of numerous canals. It is the centre of the commerce of this fertile province, the town of Bingeh [Saigon] being but little engaged in such pursuits. A few settlers from China carry on trade on an extensive scale, but the Cochin Chinese are for the most part too poor to engage in occupations of this nature.

We landed in about the middle of the town, and after proceeding a short way, we entered the house of a Chinese. He received us with great civility, and invited us to partake of refreshments; he said that he was anxious for traffic with the English, and had now upon his hands commodities suited for that trade.

We passed several hours in visiting various parts of the town, and returned to our quarters in the evening highly gratified with all we had seen, and with the most favourable impression of the manners and disposition of the people. The attention, kindness and hospitality we had experienced so far exceeded what we had hitherto observed of Asiatic nations, so that we could not but fancy ourselves among a people of entirely different character. We were absolute strangers who had come to pass a few hours only in the town; yet in almost every street we were invited by the more wealthy Chinese to enter their houses, and to partake of refreshments. They could not have known beforehand that we were to visit the place, yet some of the entertainments laid out for us were in a style of elegance and abundance that bespoke the affluence, as well as the hospitality, of our hosts.

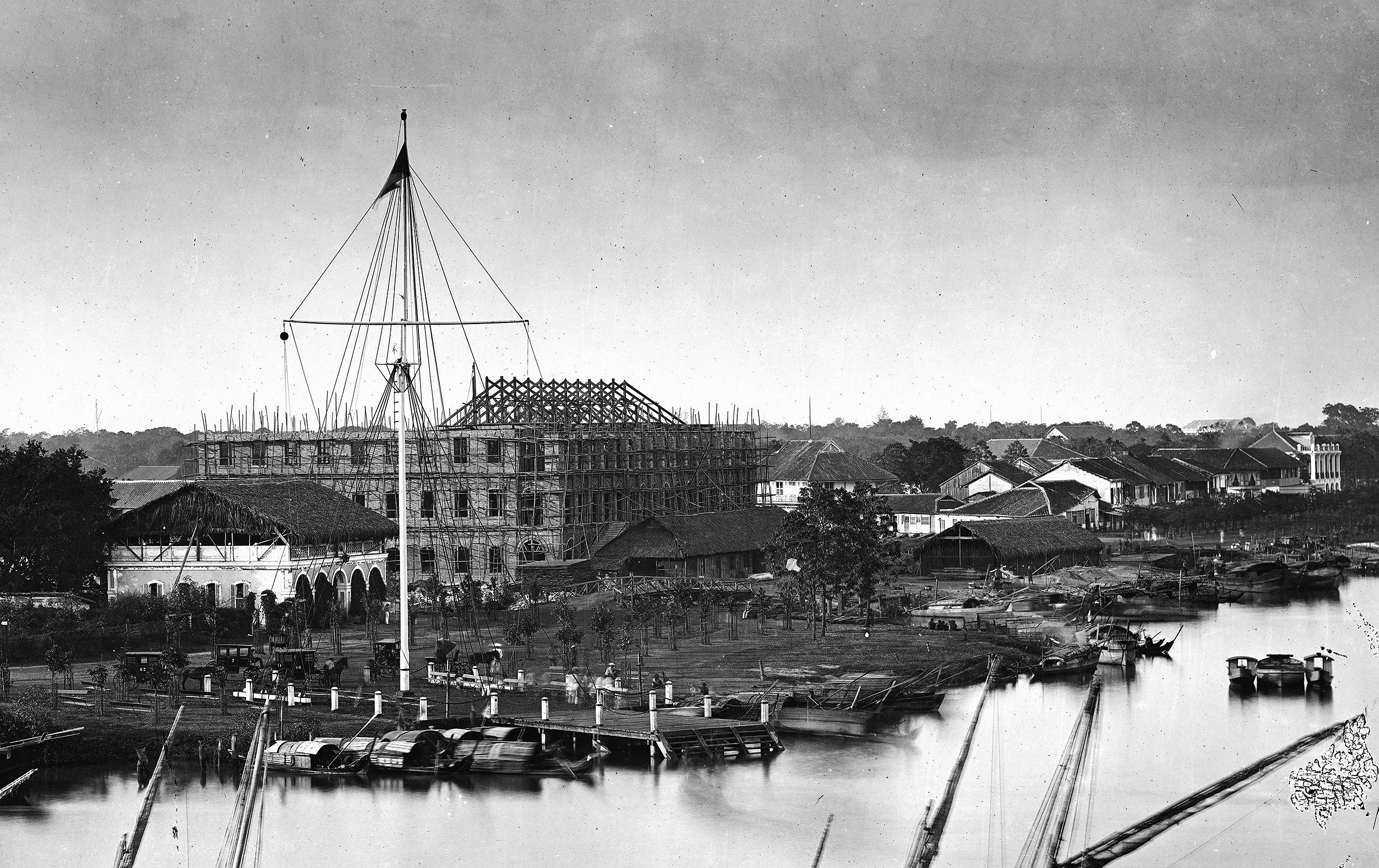

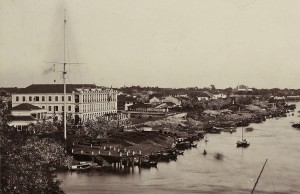

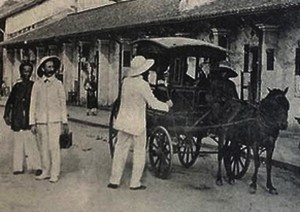

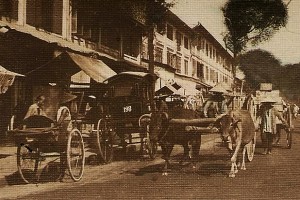

An early colonial shot of the Saigon River by Emile Gsell

Amongst others, we were invited by three brothers who had been settled in the country for some time. They wore the Cochin Chinese dress, and in appearance differed but little from the native inhabitants. Their manners were engaging, perfectly easy and polite; their house was both handsome and spacious, nor did anything appear wanting to render it a very superior mansion, even in the opinion of a European. They received us in a large, well-furnished ante-room; a table was soon covered with a profusion of fruits, the most delicate sweetmeats, and a variety of cakes and jellies. They insisted upon attending us at table themselves, nor could they be induced to seat themselves while we were present. Tea was served to us in small cups; a large table was also spread for our followers, who were supplied with sweetmeats in profusion. Our hosts conversed but little; they were apparently as much pleased with our visit as we were with the kind reception they had given us.

Let others say from what motives so much hospitality and attention were bestowed upon perfect strangers by these intelligent and liberal-minded Chinese; for my own part, I must do them the justice to believe that they were of the most disinterested nature.

The bazaars of Saigon [Chợ Lớn] contain in greater abundance all that is to be found in those of Bingeh [Saigon]. Coarse China and Tonquin crepes, silks and satins, Chinese fans, porcelain, etc, are the more common wares in the shops. The streets are straight, wide, and convenient, the population extensive. We entered a very handsome Chinese temple, built in good taste and highly ornamented. The Cochin Chinese temples, though apparently dedicated to the same objects of worship, are of inferior appearance.

September 2nd: We were told that the Viceroy would give an audience to the Agent of the Governor General at an early hour. At about 10am, the mandarin who had conducted us from the ship came to say that the Viceroy awaited our arrival.

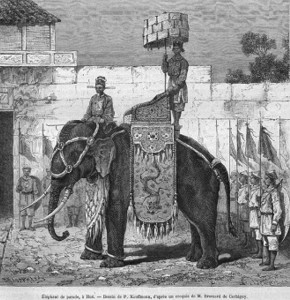

Being asked what conveyance had been prepared for us, he said that we must proceed on foot. This being objected to, five elephants were sent for. These were furnished with howdahs, such as are used by the natives of India.

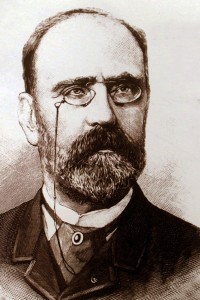

Royal Viceroy Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt (1763 or 1764–3 July 1832)

A few minutes’ journey brought us into the Citadel, where the Viceroy resides. His house, though large, is plain, and without ornament, in the interior or exterior. It is situated nearly in the centre of the fort, in an open space. When we had arrived within 50 yards of the entrance, we were requested to descend from our elephants and to proceed the remainder of the way on foot. A crowd of soldiers, armed chiefly with spears, occupied both sides of the court. The Viceroy, surrounded by the mandarins, was seated in a large hall, open in front. We advanced directly in front of him, and, taking off our hats, saluted him according to the manner of our country. Chairs had been provided and we took our seats a little in front, and to the right of the mandarins. In the back part of the hall sat the Viceroy, upon a plain, elevated platform, about 12 feet square, and covered with mats, on which were laid one or two cushions.

On a lower platform to his left, and a little in front, was seated his Deputy, a fine looking old man, who appeared to have passed the age of 70. Directly opposite to the latter, about a dozen mandarins dressed in black silk robes were seated in the Indian manner, on a platform similar to that opposite; and behind these stood a number of armed attendants, crowded into one place. In front of the Viceroy, two Siamese, who had come hither on their private affairs, lay prostrate on the ground, in the manner that they attend upon their own chiefs.

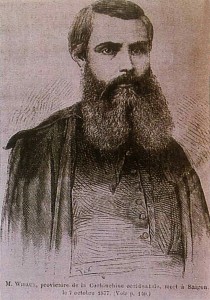

The Viceroy of Saigon [Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt] is reputed to be a eunuch and his appearance in some degree countenances that notion. He is apparently about 50 years of age, has an intelligent look and may be esteemed to possess considerable activity both of mind and body: his face is round and soft, his features flabby and wrinkled; he has no beard, and bears considerable resemblance to an old woman: his voice, too, is shrill and feminine; but this I have observed, though in a less degree, in other males of this nation. His dress is not merely plain, but almost sordid, and to the sight as mean as that of the poorest person.

He had requested that the letter from the Governor General of Bengal should be brought with us to the audience. Seeing it in my hand, he enquired what it was I held; and having examined the gold cloth in which it was contained, he returned it, at the same time observing that having, according to the custom of the country, taken copies, it must not be again opened.

Civil (left) and Military (right) Nguyễn dynasty Mandarins (about 1820), an illustration from John Crawfurd’s own Journal of an Embassy to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China, exhibiting a view of the actual State of these Kingdoms, London, 1828

He now enquired how long it was since we left Calcutta, and what our respective ages were. He observed that it was customary only for kings to write to kings. “How then,” asked he, “can the Governor General of Bengal address a letter to the King of Cochin China?”

He seemed to comprehend what the objects of the mission were and to view them in a favourable light. “All ships,” he observed, “are permitted to trade with Cochin China. “If,” he continued, “the subjects of the King of Cochin China visit Bengal or any other British settlement, it is right that while there, they should be amenable to the laws of the country and be judged by them in like manner that the subjects of other nations resorting to Cochin China should be governed and judged by the laws in use in that country; and that otherwise there could be no strict justice.”

He asked if we were going direct to Turon [Tourane, now Đà Nẵng] or to the port of Huế, and what conduct the Agent of the Governor General meant to pursue on arriving at that place. He was told that a report of our arrival should be immediately forwarded to court from that place; on which he observed that the Mandarin of the Elephants was in charge of matters of this nature, and would give all requisite information on the subject of commercial affairs.

I have described above, in general terms, the nature and extent of the conversation that transpired. The mandarins appeared to be perfectly at ease in the presence of the Viceroy, exhibiting neither fear nor awe of any kind. They frequently addressed questions to us during the interview. The conversation was carried on through the medium of the Portuguese language, by means of a native called Antonio.

Towards the close of the conversation, Monsieur Diard came in, dressed in the style of a mandarin, and took his seat beside us. Tea was offered to us, according to the usual custom.

Elephant and tiger fights remained a popular recreational activity at the Nguyễn dynasty court well into the 20th century, as shown in this illustration from the Small Illustrated Newspaper of 9 October 1904

In front of the hall was a cage containing a very large tiger, which the Viceroy had caused to be caught, in order that he might exhibit to us a fight between that fiercest of animals, and the elephant. We were asked if the spectacle would be agreeable to us, and on our replying in the affirmative, he gave the necessary directions on the subject.

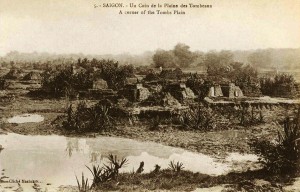

In the midst of a grassy plain, about a half a mile long and nearly as much in breadth, about 60 or 70 fine elephants were drawn up in several ranks, each animal being provided with a mahout and a howdah, which was empty. On one side were placed convenient seats; the Viceroy, mandarins, and a numerous train of soldiers being also present at the spectacle. A crowd of spectators occupied the side opposite.

The tiger was bound to a stake and placed in the centre of the plain by means of a stout rope fastened round his loins. We soon perceived how unequal was the combat; the claws of the poor animal had been torn out, and a strong stitch bound its lips together, preventing him from opening his mouth. On being turned loose from the cage, he attempted to bound over the plain, but finding all attempts to extricate himself useless, he threw himself at length upon the grass, till seeing a large elephant with long tusks approach, he got up to face the coming danger. The elephant was by this attitude, and the horrid growl of the tiger, too much intimidated, and turned aside, while the tiger pursued him heavily, and struck him with his fore paw upon the hind quarter, quickening his pace not a little.

The mahout succeeded in bringing the elephant to the charge again before he had gone far, and this time he rushed on furiously, driving his tusks into the earth under the tiger, and lifting him up, gave him a clear cast to the distance of about 30 feet. This was an interesting point in the combat; the tiger lay along on the ground as if he were dead, yet it appeared that he had received no material injury, for on the next attack, he threw himself into an attitude of defence, and as the elephant was again about to take him up, he sprung upon his forehead, fixing his hind feet upon the trunk of the former.

The elephant was wounded in this attack, and so much frightened that nothing could prevent him from breaking through every obstacle and fairly running off. The mahout was considered to have failed in his duty, and soon after was brought up to the Viceroy with his hands bound behind his back, and on the spot received a hundred lashes of the rattan.

A Nguyễn dynasty elephant parade

Another elephant was now brought, but the tiger made less resistance on each successive attack. It was evident that the tosses he received must soon occasion his death. All the elephants were furnished with tusks, and the mode of attack in every instance, for several others were called forward, was that of rushing upon the tiger, thrusting their tusks under him, raising him and throwing him to a distance. Of their trunks they evidently were very careful, rolling them cautiously up under their chins. When the tiger was perfectly dead, an elephant was brought up, who, instead of raising the tiger on his tusks, seized him with his trunk, and in general cast him to the distance of 30 feet.

The tiger fight was succeeded by the representation of a combat of a different description. The object of it was to show with what steadiness a line of elephants was capable of advancing upon and passing the lines of the enemy. A double line of entrenchments was thrown up, and in front of it was placed upon sticks a quantity of combustible matter, with fireworks of various descriptions, and a few small pieces of artillery. In an instant, the whole was in a blaze, and a smart fire was kept up. The elephants advanced in line, at a steady and rapid pace, but though they went close up to the fire, there were very few that could be forced to pass it, all of them shuffling round it in some way or other. This attack was repeated a second time, and put an end to the amusements.

The Viceroy now called us to the place where he was seated, and said it would be agreeable to him if we would remain another day to see the city; and that a comedy should be prepared for our amusement. However, Mr Crawfurd stated our reasons for wishing to depart, and we took our leave of him, much gratified with the attention he had shown us.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.