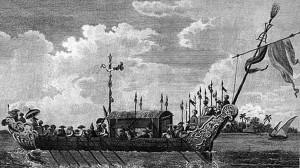

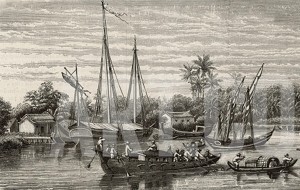

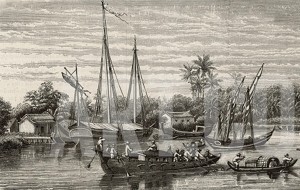

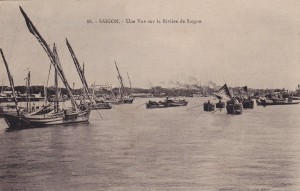

The arrival of a courrier vessel in Saigon

C Vray is the pseudonym of an anonymous Frenchwoman, wife of an unknown French marine infantry captain, whose first book, Mes Campagnes, par une femme. Autour de Madagascar, became an unlikely best-seller in 1894. Her equally popular second book, Mes Campagnes, par une femme. Cochinchine et Chine (J Girieud, Rouen, 1904), includes another fascinating, if in parts condescending, account of early 20th century life in colonial Saïgon, here translated into English.

Arrival in Saïgon

Many on our “floating city” rejoice when they signal that we’ve arrived off cap Saint-Jacques and on the horizon we can make out the low range of little mountains which border the coast, garlanded in green, with their reddish peaks gilded by the sun.

Many, I tell you, who with pleasure have travelled by these China Seas, rejoice at the prospect of a two-day stopover in this, the most attractive of cities in the Far East.

The cap Saint Jacques lighthouse

For the rest of us – captive birds whose wing feathers have been cut and who will only be released in two years time – we are in no hurry to land.

With that passage ends the attractive part of the trip, and there now commences the part which, despite everything, I call “exile.”

It takes us five hours to travel up the river and reach Saïgon.

This river is as wide as the most beautiful rivers in the world and divides into many other waterways that spread their arms throughout the surrounding lands, taking with them to their natural limits countless mangroves.

The mangrove, perhaps the most widespread plant in the world, but unknown to the people of Europe, reigns supreme throughout the lower region of this country.

This was the first “agent of conquest” of firm land over ocean; it was this which, pushing into the shallows, began to stem the rivers, striking its roots all around into the alluvium, gradually piling up and creating the beginnings of the continents.

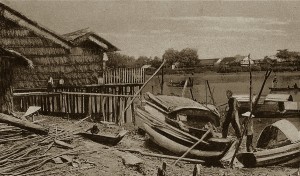

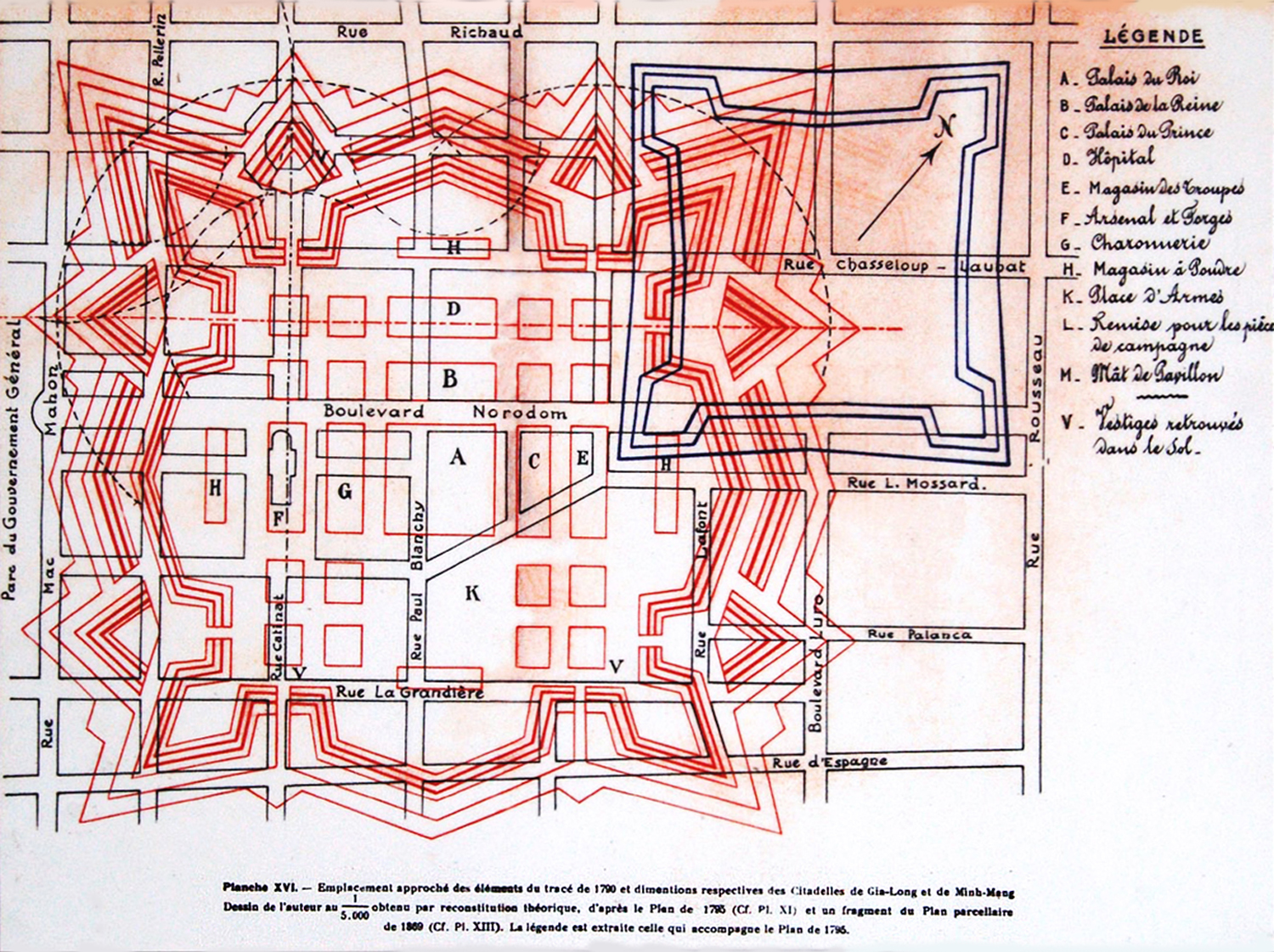

The Saigon River in 1904

It was onto land of sufficient height, uncovered at low tide, that the Annamite [Vietnamese] arrived and raised his dykes, successfully protecting this new ground from the flow of water and installing his rice fields on it.

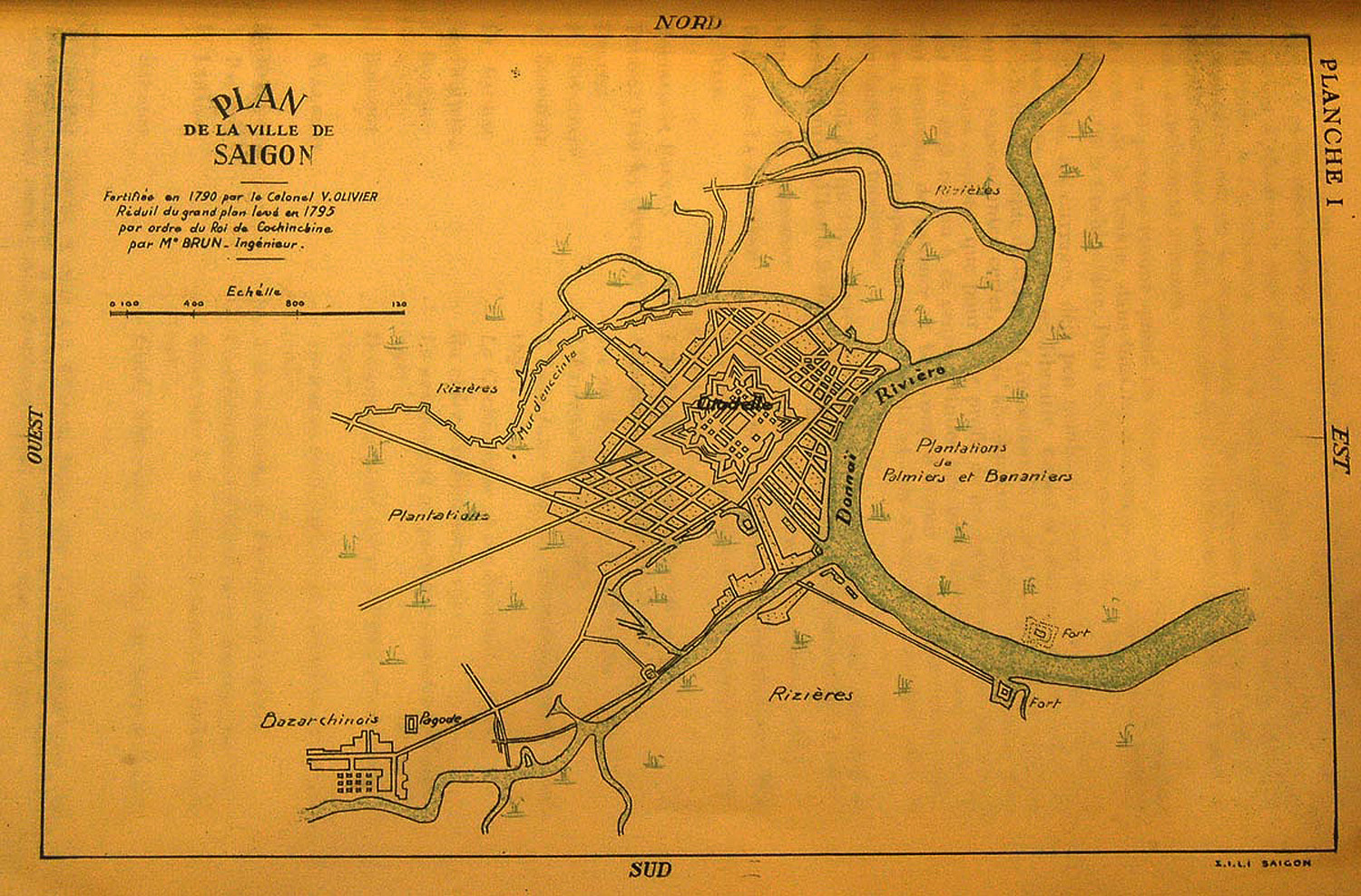

One has, in continuing up the Donai river by one of its many mouths, immediate and eloquent demonstration of this slow process, the work of many centuries, and one sees here the full progression of the conquest of the land, the conquest of man over the oceans.

Throughout the first part of the journey up river, we glide between two banks of greenery.

At first, the mangroves are completely in water, but then bit by bit, eddies produced by our ship begin to break onto mudflats.

There is still no-one living next to the river here, just groups of monkeys swinging from branch to branch through the trees.

Then we see the first, imperfect rice fields; the soil is so soft that it is hard for the native to raise his modest crops, even on one of the drier corners which he has secured with who knows how much toil! His house appears to be resting on the water.

A view of the Saigon River taken between 1900 and 1910

And yet, passing his time in the silt, he has found a way to cheat the ground, and also to find its complement of food from fishing.

The mangroves do not stop, and we see fishermen all along the river, penetrating, in their sampans, the innumerable small channels created by the currents in the midst of this sea of vegetation.

Our ship rises high above this scene; by now we are almost shaving the banks of the river, and if it had been a sailing ship, the masts would have caught in the trees, but as we speed along we have only our chimneys, the smoke from which loses itself in the canopies of the coconut trees.

We pass the “four arms,” this gigantic confluence that forms like a sea, and almost immediately, some old Cochinchinois gentlemen on board points out to us the twin towers of the Saïgon Cathedral, which stand out like two tiny points on the horizon.

But since much else on the river is attracting the attention of the passengers, there is a continual back and forth from one side of the ship to the other to show those who have not yet noticed the famous towers, now the focus of everyone’s opera glasses.

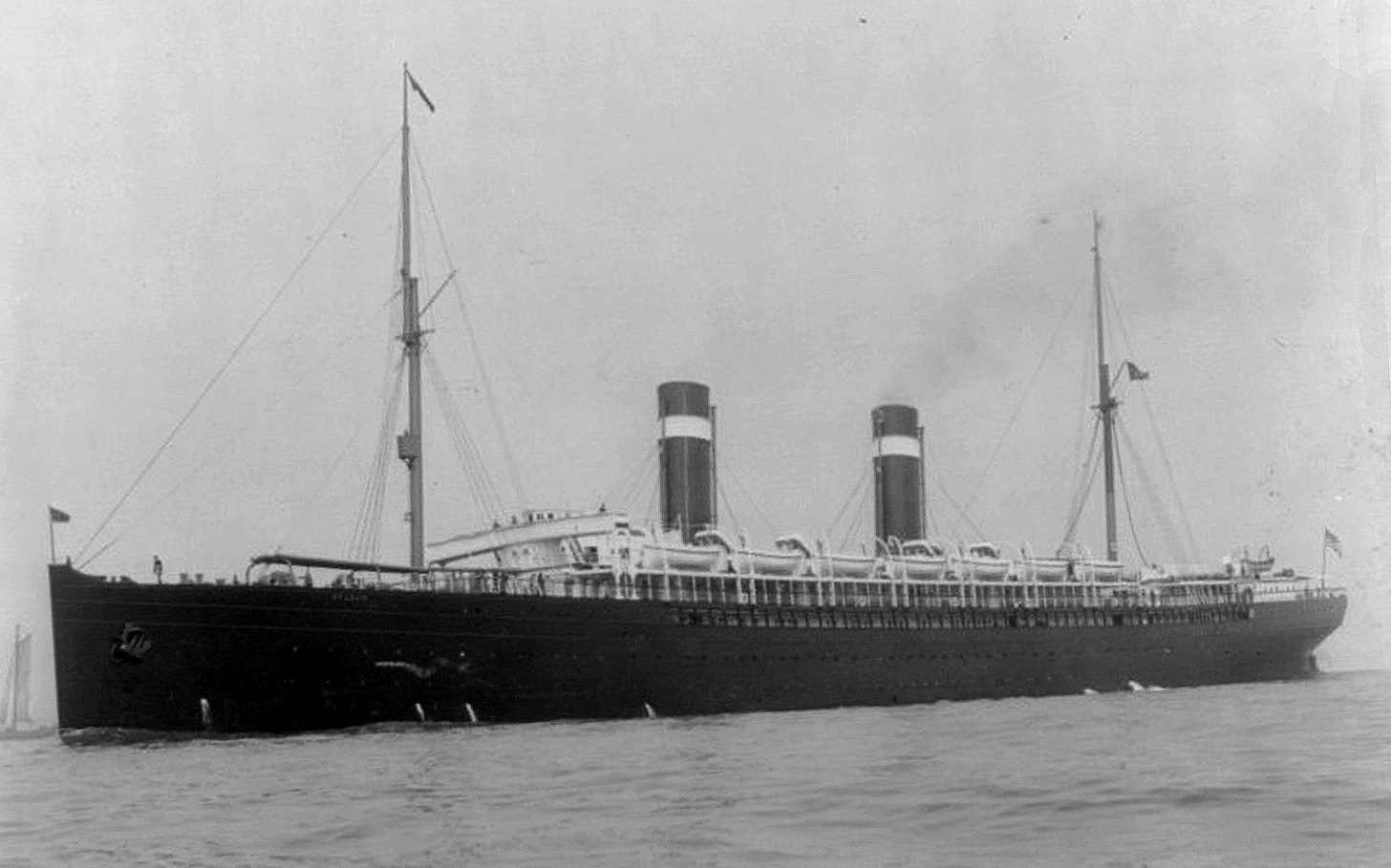

The Galissonnière-class ironclad steam frigate La Triomphante, which ended her days in Saigon

Finally we have nearly arrived. We leave the Donai to enter the Saïgon River.

Sampans gather around us and the city begins to take shape; we can see the buildings of the Sainte-Enfance and the masts of the Triomphante, an old French steam frigate which now serves as a pontoon.

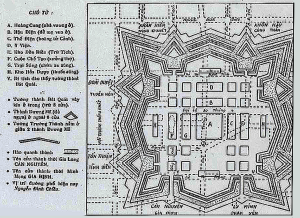

We are surprised by a sudden cannon shot; it is our post ship signalling its arrival, as we pass the Fort du Sud, an old Annamite fortification.

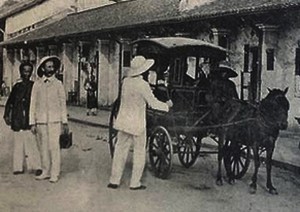

Saïgon, paralysed with the heavy sleep of the siesta, seems insensitive to the arrival of the French boat which carries us and the news from home, which is always so eagerly expected. Only a few carriages are waiting at the dock: malabars, rickshaws and victorias.

One of the latter is in charge of us and our many packages, and after we have bade farewell to the ship, we take the road into the city.

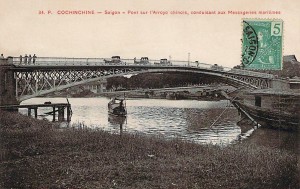

At the outset, the ride is not particularly enchanting; we travel first through a poor indigenous village comprising huts built over the swamp, which has almost a savage aspect, so we breathe a sigh of relief as soon as we see the huge bridge [the Pont des Messageries maritimes] constructed over the arroyo Chinois, which separates this suburb from the city.

Eiffel’s pont des Messageries maritimes (1882)

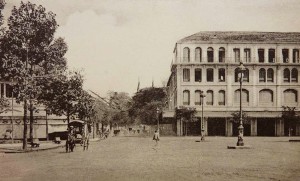

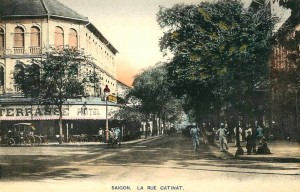

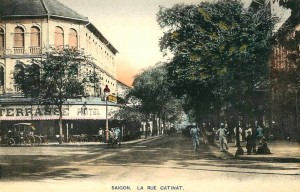

Those who have already stayed in Saïgon – and there are many, since the organisation of the colony will always return the same officials – feel their heart beating as they see again the familiar corners of this beautiful colony: the pointe des Blagueurs, the café de la Rotonde, and of course, the famous rue Catinat [Đồng Khởi street]. This latter street leads from the quayside into the heart of the city.

Despite the oppressive heat, I am suddenly gripped by the urge to take a short trip around our new garrison and I am amazed at all that I see there.

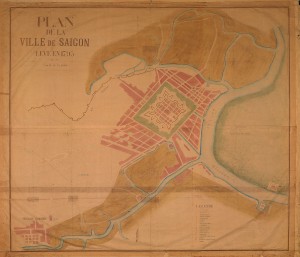

Saïgon, in short, is a very beautiful city which seems to have been created within an immense park.

The way she was designed – the grace of her lines, her curves, if one may explain a city in this way – is one of her best qualities.

Yet it is as the crow flies that the city ought to be seen, high above its monuments, its beautiful avenues with trees planted so prettily. We need to hover high above this city to understand it better.

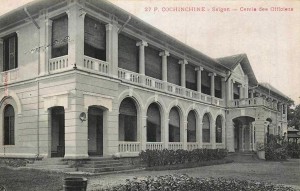

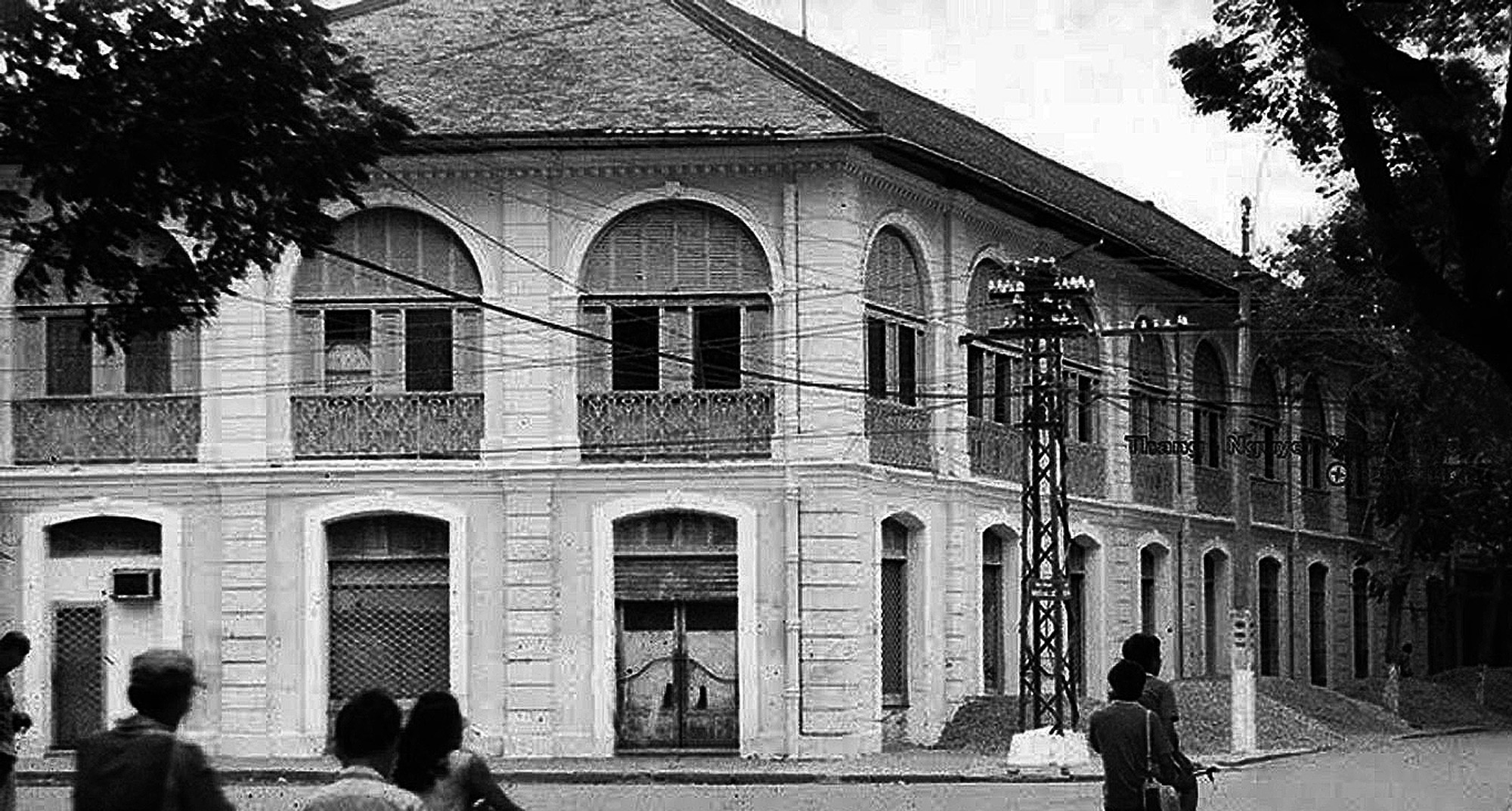

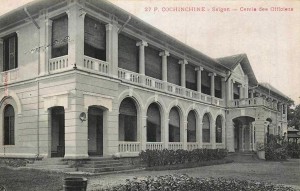

The Officers’ Club (Cercle des Officiers), built in 1878

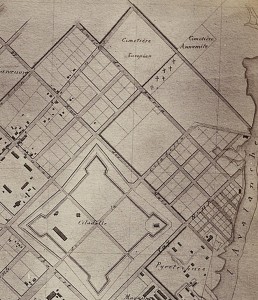

All of its streets are wide, spacious and lined with beautiful trees and squares. Its remarkable monuments include a Post Office, the like of which cannot be seen in many cities in Europe; the Cathedral, charming in its simplicity with its two bell towers; the Governor’s Palace; the Courthouse; the Military Hospital, its buildings located amidst lush gardens; the Officers’ Club, situated on one of the finest boulevards; the Infantry Barracks on the same road; the immense and beautiful public gardens; and the Municipal Theatre. All of this ensemble denotes a plan skilfully designed from the outset and executed with a rare consistency, and at the same time gives us a complete impression of French good taste.

Life in Saïgon

There is one particular hour of the day when we can experience something which would never be seen during the hot hours of the siesta.

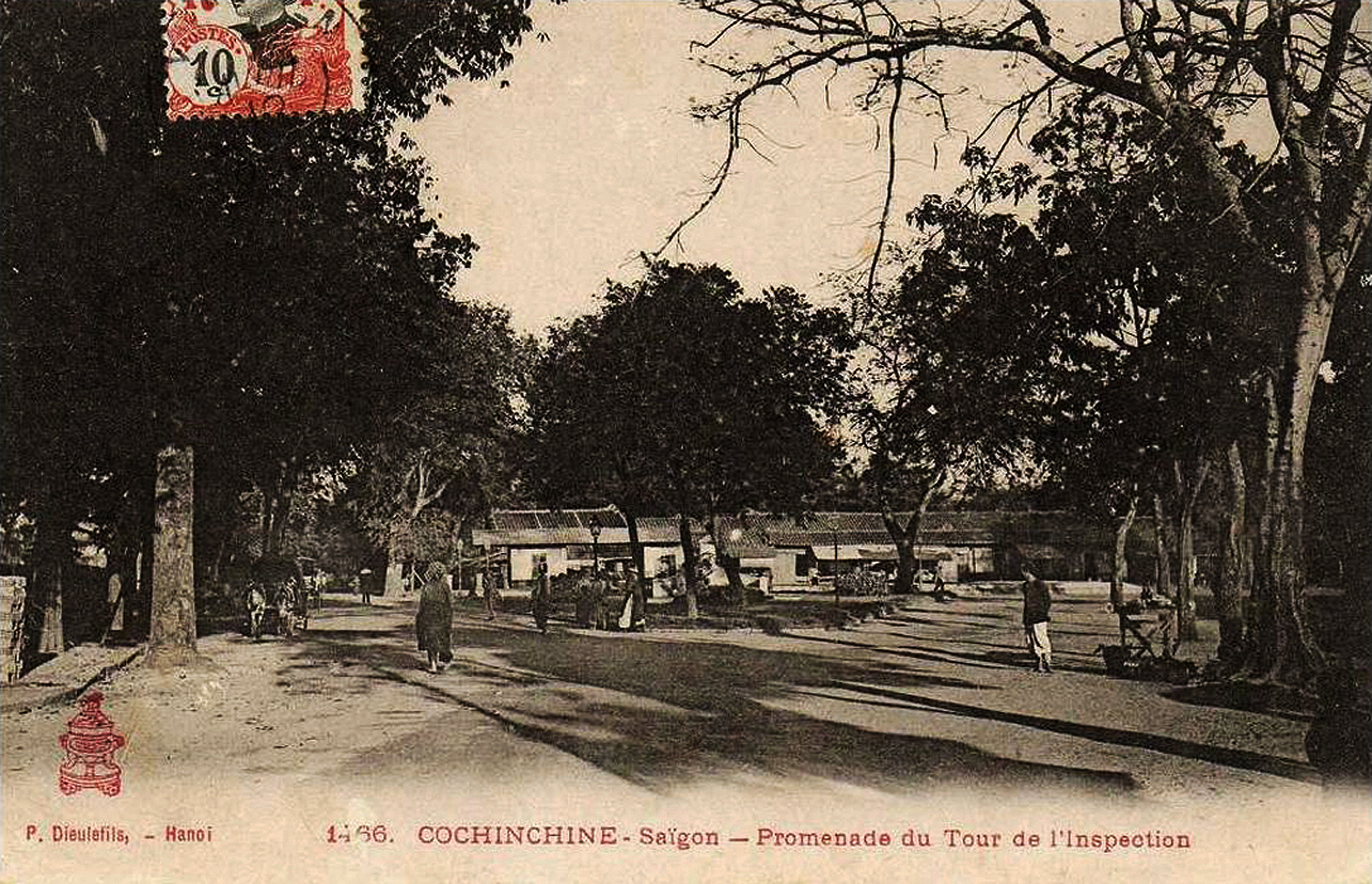

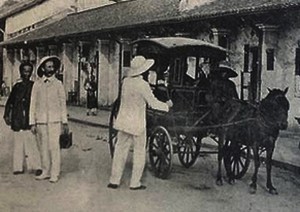

At around 5pm, the offices empty and the avenues begin to fill with people. Carriages drawn by strong little horses and driven by horsemen in smart white suits gather for the traditional promenade, the tour of Saïgon, which is known as the Tour de l’Inspection, because it takes a circular route which passes the Inspection de Gia-Dinh, situated in the nearest village.

The Aviary of the Botanical and Zoological Gardens

We travel first through the Botanical and Zoological Gardens, one of prettiest places in Saïgon, where wild beasts are graciously presented – in cages, don’t worry! – hidden behind clumps of bamboo or flower beds.

The aviary, which contains a comprehensive selection of the country’s birds, is a small house with a circular verandah, paved with mosaics and covered with creeping vines.

The monkeys, as always, bring joy to every child.

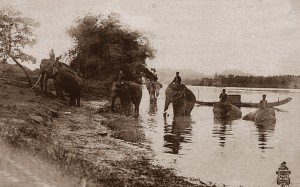

The elephant is an animal of spirit who appreciates what you give him. He is trained to take money from visitors, with which he then “buys” bananas from his keeper, but he will only accept sous, not sapeks, which he considers unworthy of him!

Leaving the Botanical and Zoological Gardens, we cross the beautiful arroyo de l’Avalanche [Thị Nghè Creek] and the Tour de l’Inspection brings us suddenly into the open countryside of Cochinchina, with its rivers and indigenous farmers.

In the early 20th century, much of the area north of the Thị Nghè Creek was open countryside

On one section of the road, beautifully kept as are all of Cochinchina’s roads, the carriage crews stop, the cyclists and horse riders slow their pace, and everyone takes the opportunity to breathe a little fresh air. With great politeness, everyone greets those passing in the opposite direction.

Both male civilians and soldiers are in the habit of wearing suits of white cloth, of which only the buttons and braids permit a distinction between the two. Meanwhile, for the French women here, maintaining their elegance takes precedence over everything (who can blame them) and they are true slaves to fashion.

At this hour of worldliness, each one dresses and adorns herself as elaborately as she would in Paris: wavy hairstyles, small hats, high collars, leather shoes; it’s all about who is the most attractive and most charming woman in the pretty capital that is Saïgon.

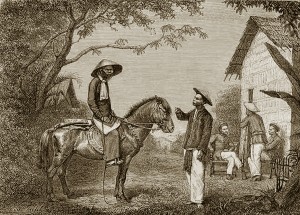

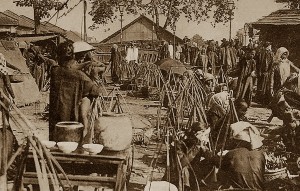

Colons arriving in Chợ Lớn

And yet it is so hot, the air is so heavy and oppressive, that I can’t help but admire, without ever hoping to match, the way in which the women of my country have adapted to this setting.That which chills your heart, however, is the pale complexion and anemic appearance of large and small alike who spend any length of time in the colony. It is a far cry from the rosy cheeks of the newcomers.

After the Tour d’Inspection, we almost always stop at one of the city’s most popular cafés, the Hôtel Continental, where the spacious terrace grants asylum to many consumers. Many bring their families here, to meet friends, to greet the new arrivals and those who have just returned from Tonkin, and we choose to do that too, in order to get to know our new military and civilian companions better.

From one end of the terrace to the other, the tables are set and a swarm of Chinese waiters, properly dressed in white, freshly shaven, pigtails at their back, run silently back and forward for syrups and ice.

Annamite flower sellers arrive with Bengal roses and jasmine bursting out of their large baskets. Chinese curio dealers try to tempt us, wantonly spreading their silks, porcelains and ivories.

The Hôtel Continental, pictured in 1905

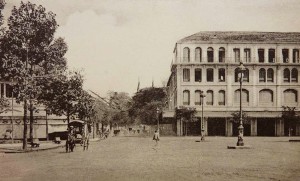

At this hour, rue Catinat is fully animated; this street by itself represents all the trades of Saïgon: attractive boutiques with the latest Paris fashions, jewellers, stationery and book shops, novelty shops, etc.

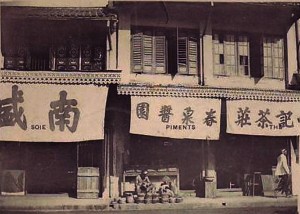

Further along, Chinese traders, grouped together as a corporation, are involved in a variety of trades for the delight of the Europeans. Their entire world – silversmiths, shoemakers, tailors, basket weavers, carpenters – may be found at the lower end of rue Catinat, where their small shops form a series of arches without doors, placed under a long gallery and spreading out onto the sidewalk.

When you walk past their stalls, all you can hear is the noise of machines, the hammers tapping against leather, it’s a real hive of activity; in front of each door swings a huge lantern-shaped balloon, decorated with Chinese characters representing the name of the owner.

And at night, after the Europeans have closed their shops and gone home, the Chinese shops remain open and brightly lit and we can still see their industrious workers toiling away until a very late hour.

The ship has docked and orders are not lacking; the old tailors can run off white suits and white shoes within as little as 48 hours, sometimes less.

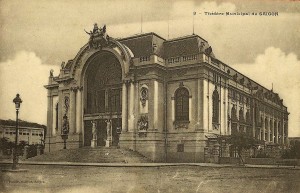

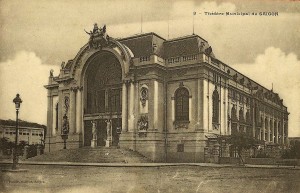

The Théâtre de Saigon, inaugurated in 1900

Night comes quickly here without twilight, and Saïgon, thanks to electricity, lights up as if by magic.

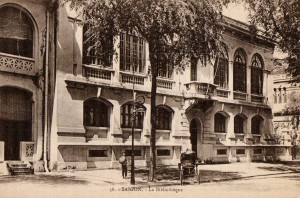

Nothing is lacking in this extra-civilised city, not even a theatre. Every year, a group is sent out from France to bring to the colony the very latest in music and literature. A new Municipal Theatre, a true artistic monument, was inaugurated in 1900.

Foreign colonies and neighbours blame us enough, but after all, the French people have literate, cultivated minds, and the French businessman of Saïgon who sells haberdashery or runs a grocery store all day long, feels the need for cultural enrichment in the evening, such as a little music, perhaps a new piece.

It can take three or four days to settle into a new house, install the furniture and recruit the necessary servants, in short to make a home where one’s brood can feel comfortable, because it is essential in this unhealthy country to have, if not luxury, then at the very least, comfort.

The civilian component of the colonial population, generously paid thanks to the wealth of the colony, and staying here for many years, albeit with leave every three years, can be settled in great comfort: house, pets, carriages, electric light and ventilation, indeed all the great conveniences of the times. However, for us wanderers, always under the threat of deplacement, we live as travellers, not daring ever to pitch our tents in a stable manner. With a colony still in its infancy, nothing other than the bear necessities seems appropriate for those of us living the military life.

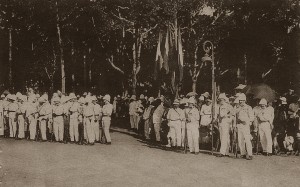

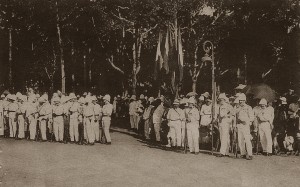

A group of French military servicemen in Saigon

The matter of domestic staff is, as everywhere, an important matter, and here we have the choice between Annamite or Chinese; The two compete with ardour to be the most deceitful towards us, and it is fair to say that both succeed well. Well trained, they are both likely to become good domestic servants; the Chinese, however, must be paid double, and if, for reasons of luxury, you choose him, you can be sure that while being a little better served, despite everything you will also be doubly robbed.

As for the children of the colony, one finds in Saïgon, to their great regret, but to the delight of parents, all desirable educational resources – colleges, religious institutions run by the Christian Brothers, a Sainte-Enfance for girls.

Once everyone goes about their business, we see a well-ordered everyday existence; the rhythm of life is established, controlled, precise, almost monotone, a real garrison life, to the delight of some and annoyance of others.

In the morning, one usually takes a healthy ride on a horse or a bicycle, according to taste, and this is followed, especially for women, by a tour of the shops in the city, the sun forcing you, from 9am, to return to the house.

The rue Catinat in the early 1900s

The heat, heavy and humid, leaves you no rest, day or night. Only the punkah fans that are wafted over the table during meals give you the courage to eat, and when, by chance, if it is not providential, the rope breaks in the hands of the native in charge of this high office, one feels like one is falling into a fiery furnace; this impression has no equal, other than the experience of waking at night under a mosquito net with a sense of suffocation, sometimes despite having a fan in one’s hand.

Yet here, one tries to fight against this temperature, against the unhealthy, debilitating and often fatal climate, by seeking pleasure in a high dosage; one gives soirées, balls, parties, big dinners; one laughs, one tries to forget the evil that lurks here, and this artificial joy becomes, sometimes, a real need.

Saïgon is the Paris of Cochinchina, it’s the city of luxury and temptation, and how many, failing to resist, have foundered miserably in a whirlwind of pleasure? One spends too much money, one spreads one’s wealth here. It’s all about who spends the most and the best in this high society life where everything can be procured at a price.

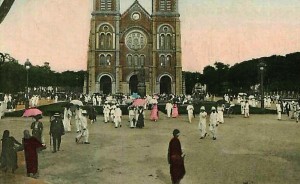

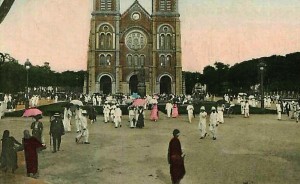

The congregation exits the Cathedral after Sunday morning mass

Every Sunday, at the 8am mass, where the bishop officiates in style, all of Saïgon’s faithful crowd into the beautiful and spacious cathedral. There, side by side, kneeling devoutly, we see the elegant Frenchwoman; the Indian dressed in silk and jewels under her discreet veil; the Annamite, graceful in her long-sleeve black silk tunic, quiffs of hair smooth like crows’ wings and retained by small silver pins; and the happy Chinese woman, who benefits from the blessings of Christian civilisation which enable her to walk freely, and who is also decked out in a silky jacket with wide sleeves and jade jewelry.

French and indigenous babies alike gurgle in front of the Lord, and throughout the gathered congregation, the sound of the wafting of fans may be heard, like the light beating of birds’ wings.

The Governor’s palace well deserves the name “Palais Norodom” which is currently given to it.

Admirably located at one end of boulevard Norodom, which opens out in front of it giving it a grandiose perspective, this princely residence, surrounded by immense gardens, offers the arriving Governor of Indo-China all the luxuries of installation that this rich colony has accumulated; on his arrival, he finds a large and well-trained staff and sumptuous carriages awaiting him at the dock, even before he lands.

The Norodom Palace illuminated at night time

But it is especially on the great festival days that one can judge this beautiful building and its happy situation, because it becomes the central point of all the festivities, and that’s where all the combined efforts to achieve success are concentrated.

On the evening of 14 July, for example, both sides of the boulevard are lined with white chandeliers and the trees in the palace garden are enflamed in multicoloured lights, while in the background, the palace itself is lit up in luminous silhouette.

It’s on this same boulevard that, for three days and three nights, one finds market stalls and Annamite theatres, a real fair which is the joy of the people; it’s also here that the great military parades take place, where one can see the Annamite riflemen marching alongside our brave marsouins.

Cholon, the Chinese city

Although the Chinese have almost a small town of their own in the vicinity of the main Saïgon market, it’s to Cholon, that great Chinese city located 4km from Saïgon, that we go shopping for silk, porcelain, tea, etc.

Travelling through countryside, we cross the entire width of the vast Plaine des tombeaux (Plain of tombs), arriving in Cholon in the evening to walk through its illuminated streets.

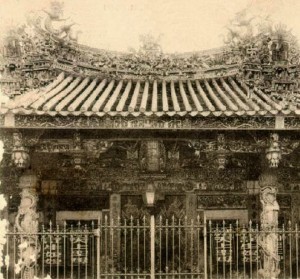

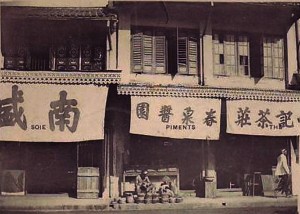

Shops in Chợ Lớn

Cholon, a Europeanised Chinese city with multi-storey houses properly aligned along wide, airy streets, has nothing in common with the cities of China.

Only a few pagodas with their multi-layered roofs decorated with dragons and curved corners, the commodities of the country, the people and the stale smell of opium, remind you that you are thousands of miles away from your country.

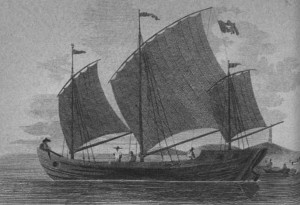

In Cholon there is a huge trade in rice and wood, and the arroyo which runs through the city, leading to Saïgon, is continuously cluttered with big junks and smaller wooden boats coming from the interior of the country via the countless canals that criss-cross it.

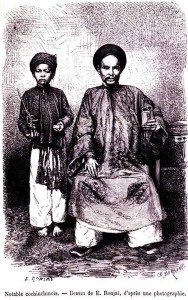

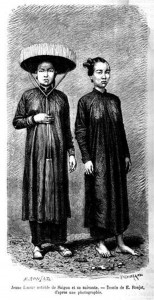

The Phu (mayor) of Cholon [Đỗ Hữu Phương] is the most important character in this place. His house, very Annamite in design, contains many treasures which he takes great pleasure in showing to his visitors.

He is a very nice man who speaks French well enough and has raised his son so completely that he was able to become a military officer and to marry a Frenchwoman. I saw her there with her babies, on holiday with her in-laws.

Governor Đỗ Hữu Phương

The Phu’s daughters are lovely Annamite women, always neat and elegant in their native dress, their small delicate hands adorned with rings; they wear pretty gold-trimmed necklaces around their necks and do the honours of their homes with as much tact and grace as the most correct young girls elsewhere in the world.

At around 10pm, the city is in full swing, with theatres, gambling houses and opium dens teeming with people. Outside, the vendors prepare the open-air restaurants, installing on the streets tables garlanded with many small and shiny lights that transform them into a veritable illumination and permit hardly any carriages, rickshaws and pedestrians to circulate.

If you want to visit an Annamite theatre, it’s best to choose that of the Phu. That amiable mandarin will receive you in a special box and offer you champagne and other refreshments. Then you can admire at leisure the actors with their fantastic colourful warrior costumes, who shout and gesticulate, declaiming before you a series of pieces which you will not understand.

But if you prefer to see the true Chinese Theatre, also embued with local colour, join the crowd which, at about 11pm, makes its way to the Chinese Theatre in the main street of Cholon. Arriving there, you will be equipped with a small lantern, which is sold to you at the door of the theatre and permits you to move at ease in its dark corridors.

The Annamite Theatre in Chợ Lớn

The entrance fee is very modest, and if you are not satisfied, simply go out and try a second or third facility; there are several in Cholon.

Whoever had the honour of receiving our merry band fails to warn us that, unlike our theatres, it is more like a huge hangar, dimly lit by the lights of the stage.

After stumbling down the shaky stairs, we place our lanterns in a corner and instal ourselves in the midst of the Chinese rabble, who seem quite at home there, well at ease, half-lying on the seats and nonchalantly smoking their long pipes of opium and tobacco; the more well-to-do rent special boxes where pure opium is smoked.

The simplicity of the staging and the lack of restraint of the actors are a joy to see.

A small orchestra consisting of a flute, a two-string violin and tom-toms, take their place below the stage, following only approximately the action of the play and pausing occasionally to attend to their own affairs.

The main Chinese Theatre in Chợ Lớn

Nothing is too difficult for the actors to perform; if they have to cross a river, they make mock rowing gestures with a stick and pretend to hoist the sail of an imaginary boat; if they want to kill someone, they make the sign of death and the doomed character falls to the ground.

The greatest quality of the players is their amazing voice, and it is on the strangeness of intonation that we judge their merit.

The play, it seems, is successful, because everyone shows his contentment with cries and great disorder. Some spectators are even moved to get up onto the stage themselves during the performance.

Eager to share with us this joy, one of our Chinese neighbours offers to explain the play in French, and nothing is funnier than the intrigues and the good or bad feelings portrayed by this good man.

That night, we see a group of sailors in the company of marine infantrymen; Chinese mothers breastfeeding their babies; many children; and above all, a very happy people.

An actress from the Chinese Theatre in Chợ Lớn

A little later, we enter another theatre. This time, an actor in colourful costume swallows swords, eats fire, juggles, and makes sparks appear from the noses and mouths of his surprised peers; he is a magician working within all the rules of the art.

At the exit, all the spectators, delighted with their evening, gather before small tables, where foodstuffs of all kinds are waiting: green, yellow and pink jellies, soup with seaweed, croquettes, macaroons, and various fruits, including oranges, bananas, watermelon and other unknown varieties appreciated only by the natives; then pale and colourless tea served in tiny cups and accompanied, for lovers of rice wine, by the traditional choum-choum.

Leaving the Chinese city to its noisy merriment, we return to Saïgon, this time along the riverfront, where some heavy sampans loaded with rice glide silently, drawing onto the sky the outline of their dark veil.

It is with joy that we experience the quiet of the night, this mysterious beauty of the tropics where the stars may be seen with an unbelievable clarity, where the starry night sky illuminates the sleeping earth.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.