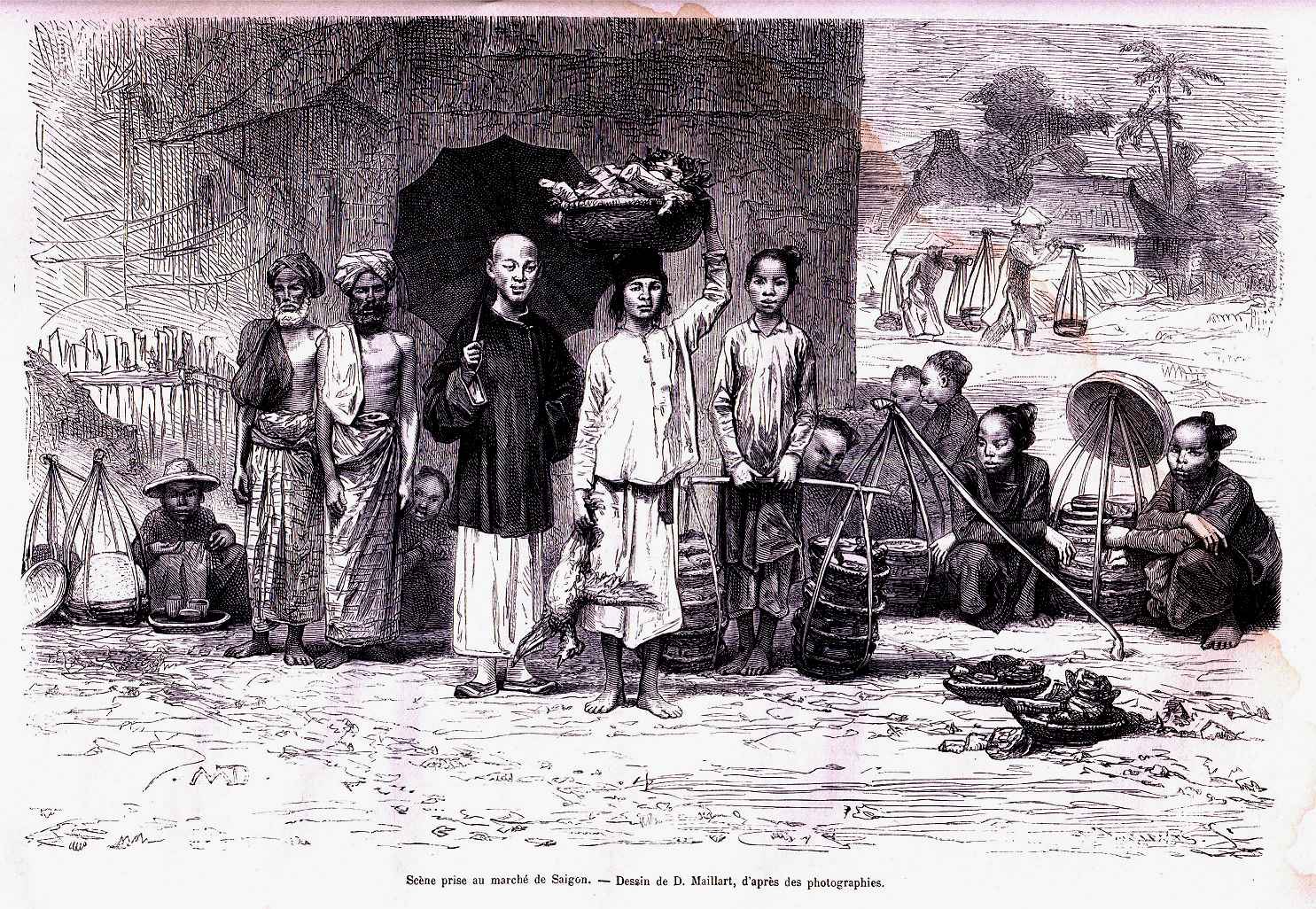

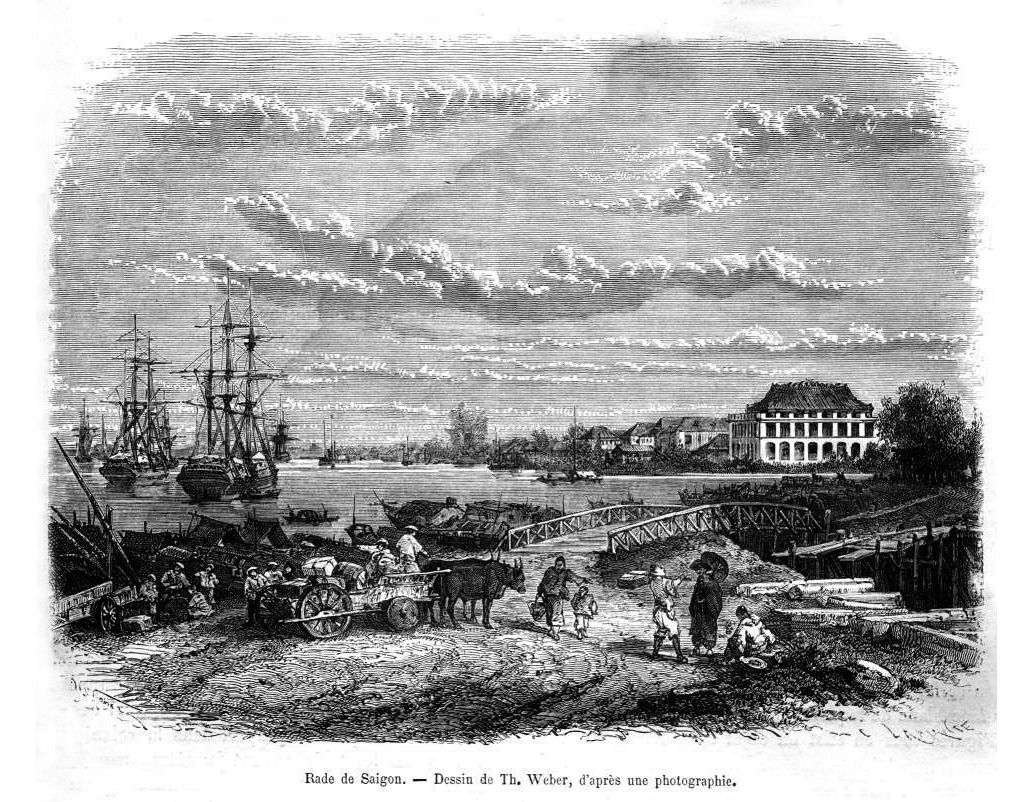

A Saigon market scene in 1875 drawn by D Maillart from a photograph

Voyage en Cochinchine, an account of naturalist Dr Albert Morice’s 1872 visit to Saigon, Chọ Lớn and the Mekong Delta, was first published in the geographical adventure magazine Tour du Monde. This is the second and final extract, translated into English.

To read Part 1 of this serialisation, click here.

Despite the hot sun and the onset of prickly heat, I still walked around the city to satisfy my curiosity, and that’s how I became acquainted with some curious specimens of Saigon fauna.

A street scene in late 19th century Saigon

In the bush, and especially in the grasslands of the city near the Carmelite Convent, I often met the Asian grass lizard (Takydromus sexlineatus), which has a tapered tail three or four times the length of its body. Its skin is dry and rough, but the scales on the tail are very sensitive to touch. Its general colour is rather difficult to define; it is a dull brown, on which run darker longitudinal bands, which in males have a tint of metallic green. It weaves its way through the tall grass with astonishing rapidity. Its character is sweet; once caught, it doesn’t try to bite, but tosses and turns between one’s fingers, waving its tail in an attempt to whip the unjust hand which holds it prisoner.

On the tamarind trees of the streets of Saigon, and often also in the middle of flowerbeds where it watches the insects, we meet the Oriental Garden Lizard (Calotes versicolor) the “Bloodsucker” of British India. This is a lizard similar in size to our green lizard, but perhaps shorter. Its tail is thin, its body rough and scaly, and its hind legs are long, allowing it to jump. Its fingers, five in number, are long with hooked nails. It has a dorsal crest and its throat is adorned with a goiter. When the animal is excited, this goiter, along with the front legs, the head, the neck and the crest, turn a beautiful green or azure colour. Behind the eye, there is a yellow or black spot. The head is large, flat and heart-shaped, covered with very small scales; the jaws are armed with very sharp and evenly-sized teeth, apart from two upper and lower canines which are powerful enough to pinch painfully, but not draw blood. When one catches this lizard by the tail, it will not foolishly leave this important appendage in the hands of its attacker, but instead will await its fate, motionless, with its mouth ready to bite. Its manner of climbing trees is curious: if it sees you, it flattens itself against the bark and crawls slowly round to the opposite side; if you approach, it quickly climbs higher by spiralling around the trunk, stopping occasionally to tilt its head towards you.

I nimbly placed my left arm above the animal and tried to catch hold of it with my right hand. But it jumped over my arm and escaped. When I tried again, it jumped onto my shoulder and then leapt back onto the tree. It is, so to speak, the familiar spirit of all the tamarind trees of Saigon; this lizard has for enemies most types of tree snake, which value it as food, despite the thorns of its crest.

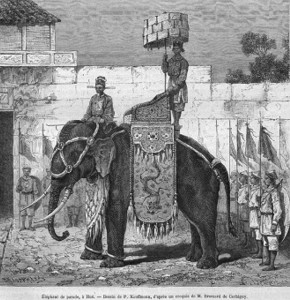

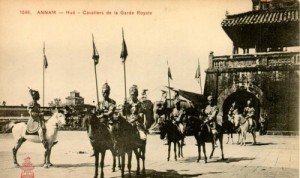

Annamite soldiers

A troupe of Annamite riflemen in Saigon

A number of Annamites have been conscripted by our government as soldiers; some, the “Linhtaps,” wear the same costume as our own marine infantrymen and are armed with chassepots [a type of bolt-action breech-loading rifle used by the French army in the late 19th century].

They are commanded by French officers and form what is called “indigenous companies.” It is interesting to see both the pride and the embarrassment with which they wear a costume that bothers them terribly. The shoes seem to be their real torture, and they take them off whenever they can. However, as they have a great deal of self respect, they are keen not to be dominated too much by Europeans and are in fact quite good soldiers, if a little difficult. What upsets them most is being forced to cut off their luxuriant hair.

The second body of Annamite soldiers we have organised is that of the Matas. These are the soldiers of the administrators. White calico pants, bare feet, a wide red belt with tobacco and betel pouches, a blue jacket with yellow trimmings and lettering indicating the Inspection to which they belong, and a small salaco with copper studs holding in place the traditional bun – this is the costume of these soldiers, among which may be found some very good individuals, but also some real rogues. They are armed with native spears and muskets.

They stand guard at the Inspections, distorting as much as possible the usual cry of warning: “Stand to attention!” We choose from among them the local NCOs: the corporals (cais), the sergeants (dois), and the quartermasters (tholaïs).

Finally, other Annamites serve on the gunboats of the state, where they often become good sailors.

Betel and tobacco

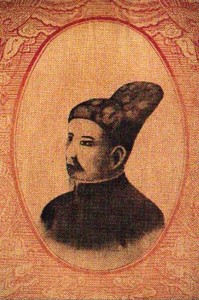

A “Cochinchinois notable” in 1875 drawn by E Ronjai from a photograph

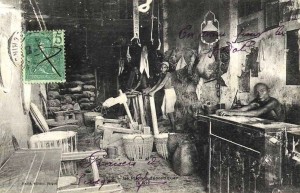

Among the vices of the Annamite race, there are two which deserve special mention: I am referring to betel and tobacco. Two thirds, perhaps, of the population of Asia and Oceania chew betel. Throughout India, all of Indo-China, and the Sunda Islands, whether they are worshippers of Brahma, Buddha, Allah or Jesus, whether they are the Caucasian or Mongolian, and regardless of age or sex, all make daily use of this complicated preparation.

The betel quid consists of the following ingredients: a betel leaf, a piece of areca nut (or the fruit of the areca palm for some wild populations), and finally a little slaked lime – white for the poor, pink for the rich. The lime is spread onto the leaf that wraps the nut; one only has to chew. The pink lime is subject to significant trade between Siam and Cochin-China, which is conducted mainly from Ha-Tien; it seems that the manufacturers use turmeric to give the lime its beautiful colour. To these three quite refined ingredients, some – especially the Hindus – add a little tobacco.

This habit, which may have some useful consequences like reducing thirst and cleansing the breath of these fish-eating populations, has the great disadvantage of rotting and decaying the teeth, colouring the saliva bright red, and condemning the user to the constant spitting of quite disgusting brick-coloured phlegm. It’s above all to the lime that these adverse effects must be attributed.

Annamites of a certain rank, especially those of the younger generation, are a little less fanatical about this perpetual rumination. As for tobacco, while the Chinese almost exclusively smoke a cigar and pipe, the Annamites prefer cigarettes. The paper is too thick, and the tobacco itself has a special smell that is immediately recognisable. The best local brand is Long-Tanh, but it’s claimed that one of the modes of preparation used by this company involves the sprinkling of buffalo urine. I give this information with all possible reserve; however, one thing’s for certain – few Europeans smoke it.

The Annamite language

The Gia Định Báo

The language of the Annamite people, monosyllabic, is enriched with many words borrowed from the Chinese language, but the basic vocabulary is absolutely different. Its mechanism is very simple, but the main difficulty is pronunciation. One understands quickly why it’s important to know the correct intonation when one realises that most words can have five or six different tones. If one’s not careful, one can make frequent gaffs which cause merciless laughter from the Annamite, who is always ready to see the humorous side of things.

A long time ago, Portuguese priests accomplished a revolution which may yet have the happiest consequences for Annamite civilisation and progress. They substituted the writing of Roman characters for Chinese characters; and thanks to the care of our administration, there are, in all centres of some importance, free schools where children are forced to come to learn to read and write in Roman characters.

In Saigon, an Annamite language newspaper known as the Gia-Dinh-Bao is printed in these characters, and there is perhaps not one 10-year-old Annamite child who does not know how to read it correctly. If one could carry out a similar revolution in China, it would be the best way to pull that huge empire out of its lethargic admiration of the past. Chinese characters, modified somewhat due to the necessities of the Annamite language, are still used for many commercial transactions, for litigation and for diplomatic documents. But their use is increasingly restricted, and that’s progress we can note with satisfaction.

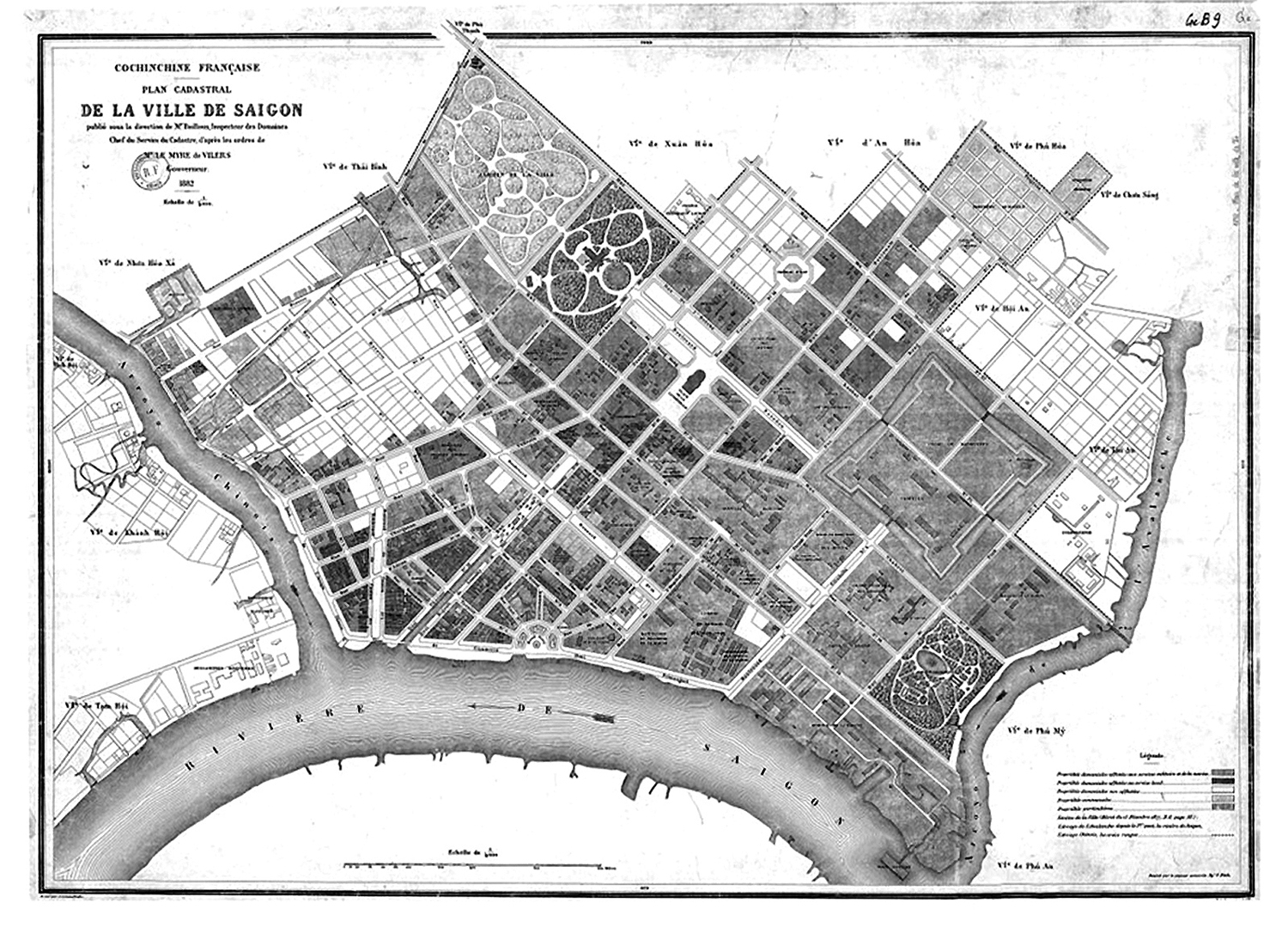

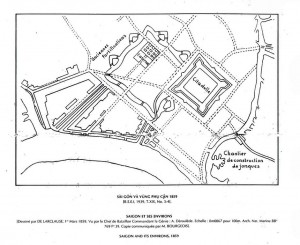

The Botanical Gardens, the Plain of Tombs and the Pigneau de Béhaine Mausoleum

Among the city’s newest and most interesting creations, we must mention the beautiful Botanical Gardens, located on the east side of Saigon. One reaches it by a street in which may be found, right next to the Sainte-Enfance [Convent of Saint-Paul de Chartres], a huge banyan tree. Thanks to the care of its director, Monsieur Jean-Baptiste Louis Pierre, the Botanical Gardens is an institution which would be worthy of adorning any of our greatest cities in Europe. This is one of the walking areas most beloved of the Saigonnais; our officers and traders come here every evening to enjoy the fresh breeze.

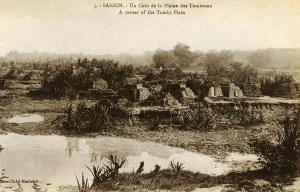

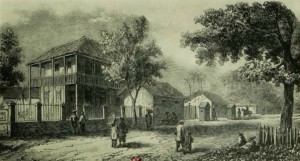

A corner of the Plain of Tombs

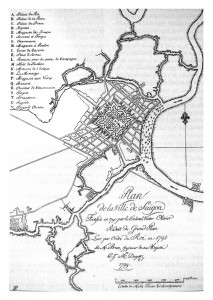

An immense plain, dotted with many rice fields and called the Plain of Tombs, extends nearly as far as the Botanical Gardens. It was there, long ago, that the battles were fought which gave lower Cochinchina first to the Annamites, and later to the French. The name of the plain derives from the numerous tombs which may be found scattered there, breaking the uniformity of its immense extent. Modest or rich, these tombs are very interesting to study. Built of clay or brick, they are covered with a kind of plaster or concrete, on which are painted fantastic animals and plants in bright colours, along with the names and titles of the deceased.

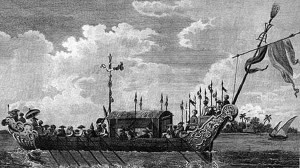

One day, while crossing this plain, I witnessed an Annamite funeral; these burials are always made with a certain luxury, and on this day the deceased was accompanied by a large retinue. The coffin was placed in the centre of a small and brightly-painted portable house, carved with strange shapes. Twenty porters carried this miniature temple, pressing their shoulders against the bamboo frame which supported it. Bearers of torches and gold and silver paper threw prayers to Buddha onto the road and set light to them. Behind the corpse walked a procession of relatives and friends.

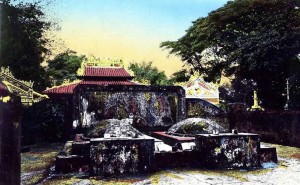

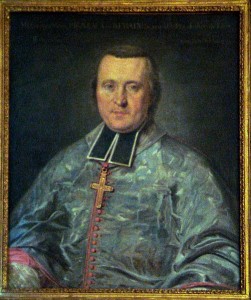

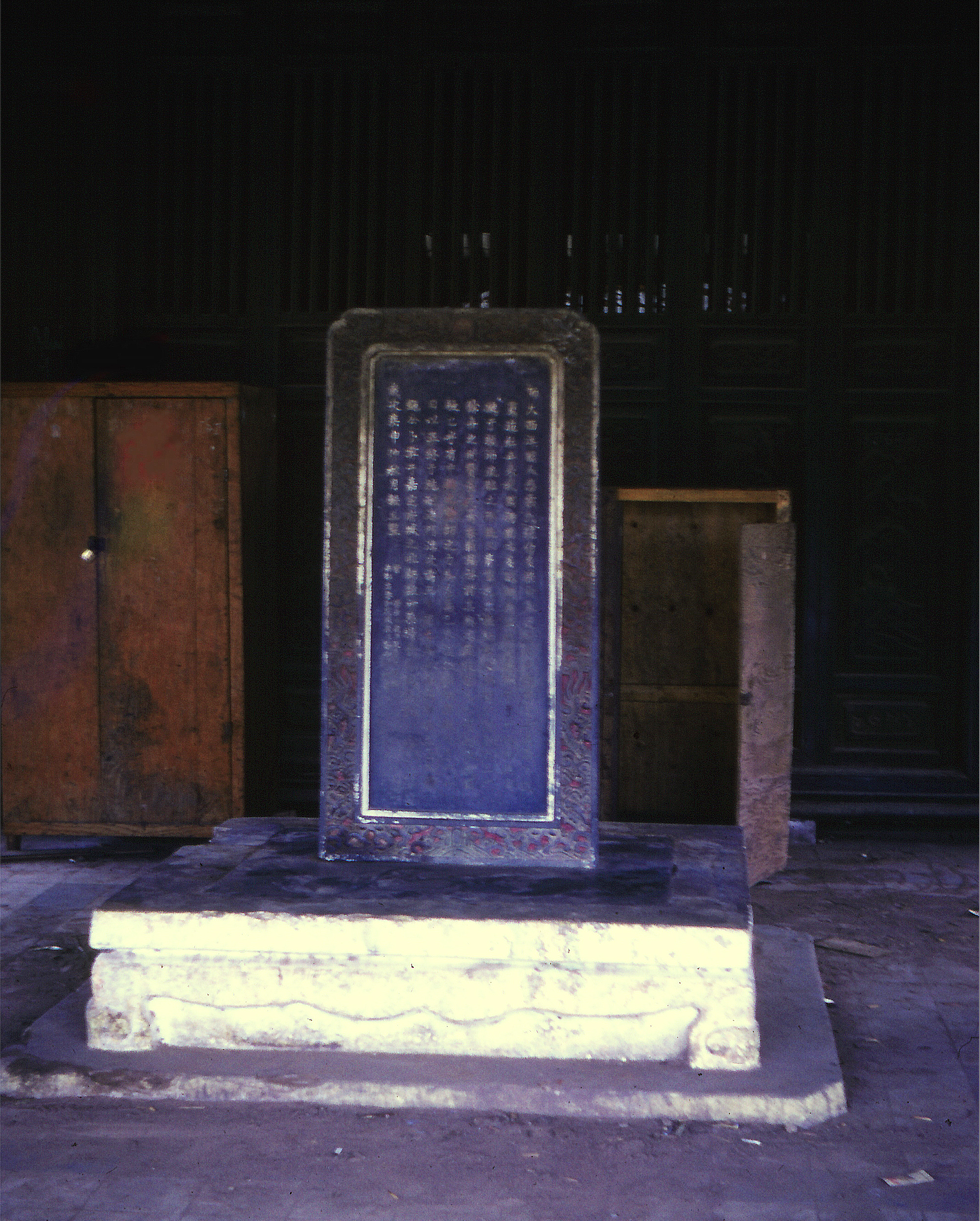

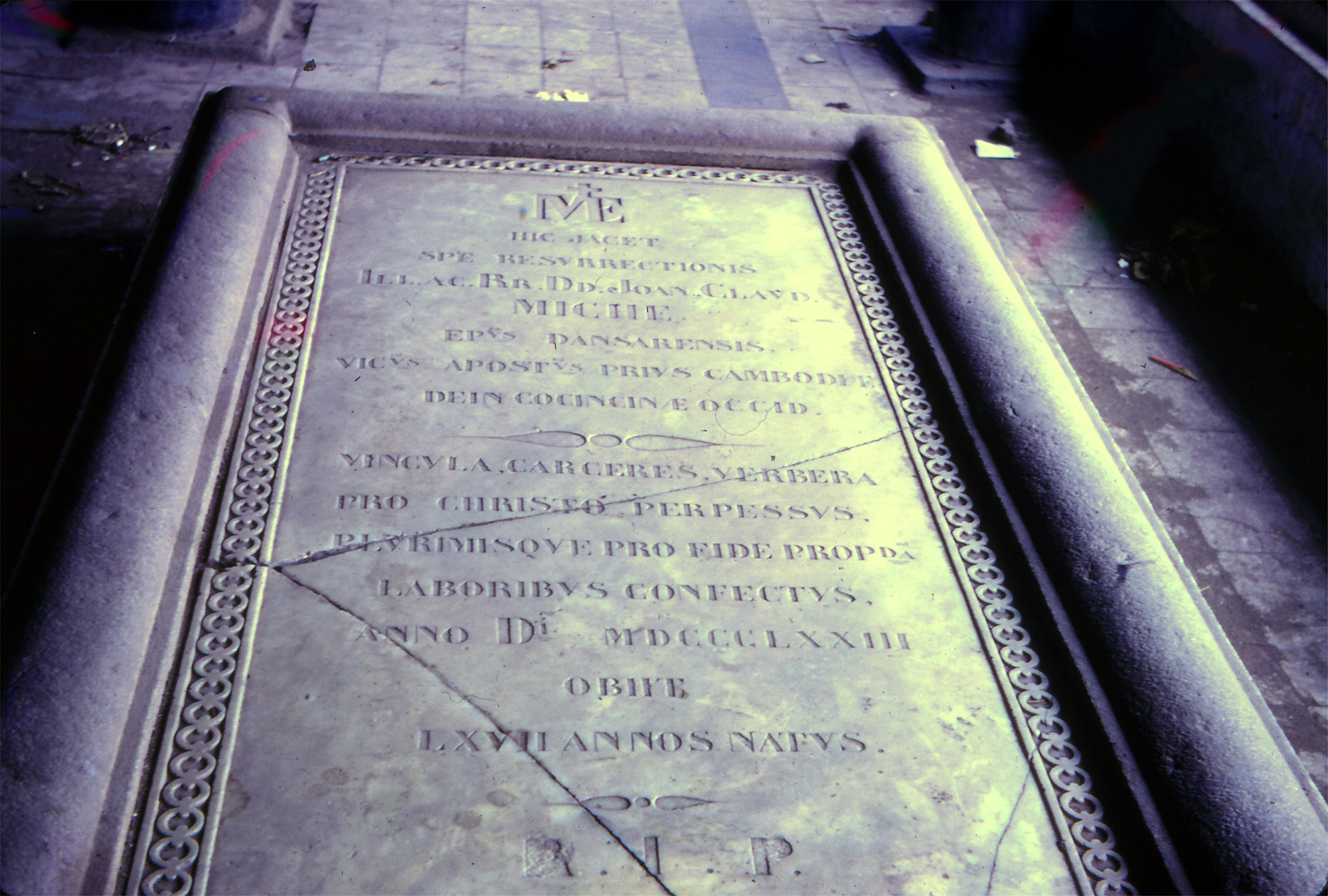

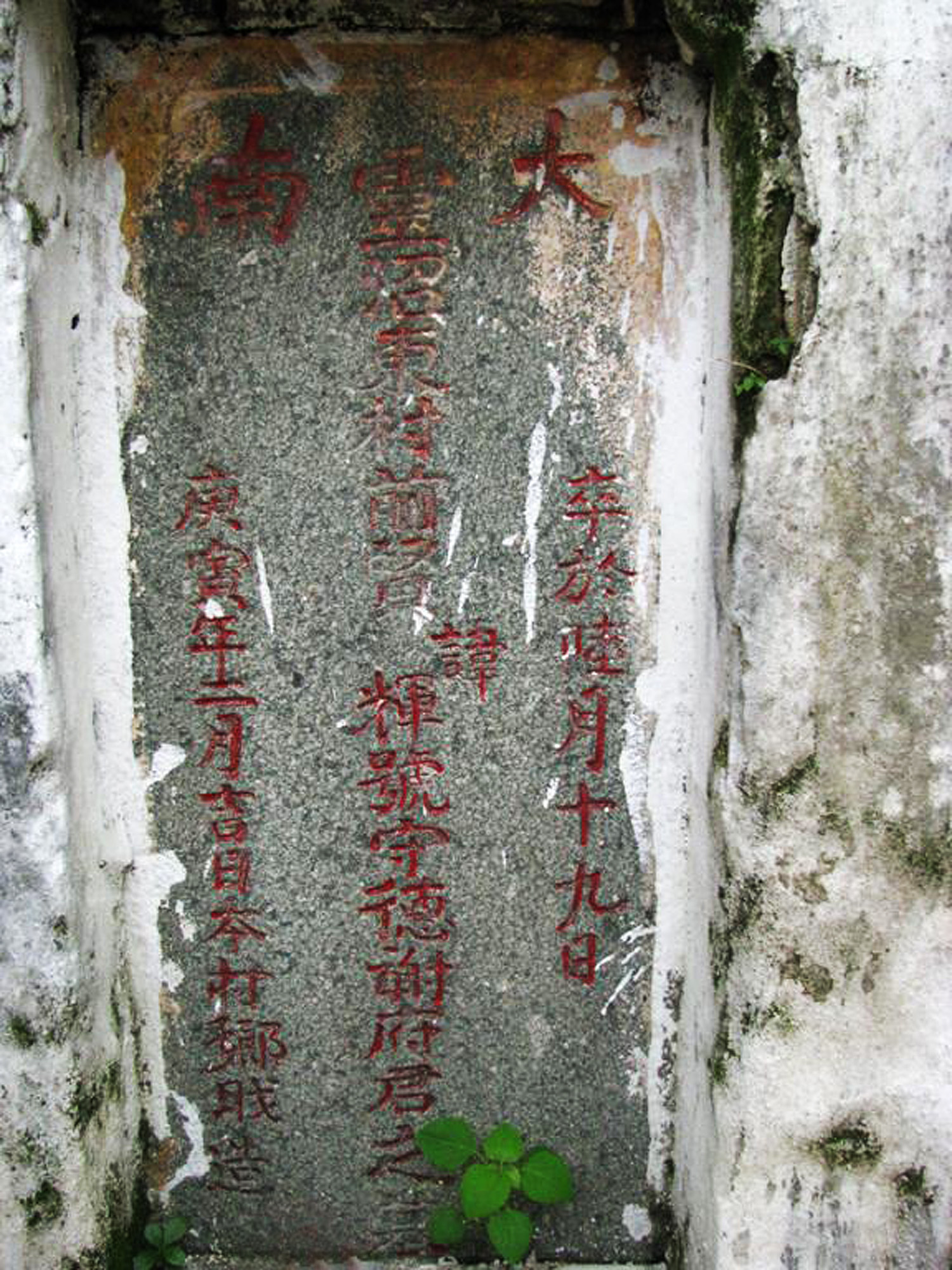

A tomb of a style similar to those of the Plain of Tombs, but much more interesting to visit, is that of the Bishop of Adran, Pigneau de Béhaine, who left lasting memories in Cochin-China. It is not far from Saigon, near the road to Go-Vap. This monument (because it deserves that name) is located within an enclosure and looked after by an attendant who opens the gate on request to visitors. The strangest frescoes by Annamite artists decorate the walls of the temple; I still remember a huge tiger with a bright yellow body and black stripes, looking menacingly at me with two large glass eyes. A large inscription in Chinese characters gives the titles and deeds of the bishop, who sleeps beneath this land which owes him so much.

The tomb of Pigneau de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran

I saw a few geckos there, which seemed to be the guardian spirits of the tomb. Living in forest and rubble, as well in the houses of both the Annamites and the French, this lizard – very common in Cochinchina – is one of the animals which give the fauna of this country its unique character. Just imagine a gigantic terrestrial salamander; on its bluish-gray skin, a number of small tubers protrude from the middle of an orange spot; its big wide eyes have a golden yellow iris, and thanks to the adhesive pads on the underside of its feet, which act like suction cups, it can walk on the smoothest surfaces, seemingly contrary to the laws of gravity. Its call, which has given the animal its name in all languages, is a very strange sound; the first time one hears it, one is almost scared. The gecko is a home-lover by nature, and never deviates much from the house it has chosen. Despite its ugliness and its call, which can be noisy when one has 10 or more of the creatures in the house talking to each other, it can be an involuntary ally of man, and as such deserves to be respected.

Another animal of the same group – though much smaller and very reminiscent of the tarente of which the Toulonnais are so afraid – is the margouillat (con-tan-lan in Annamite). These lizards live in trees and houses. Every night, by the light of the candle, we see them walking on the ceiling, where they lie in wait for insects, uttering from time to time their little cry of satisfaction, which translates as the syllable “toc” repeated 10 times. They also love sugar, and when I lie on my chaise longue after dinner, I quite often see margouillats licking the edge of a spoon or the bottom of a cup. Bitter enemies of mosquitoes, these animals are respected by all.

The Chinese theatre

Now a word about the Chinese theatre, the popular distraction of Europeans in Cochin-China. There are two kinds: one known across the world, and the other, far more interesting in my opinion, which has been less discussed; this is the puppet theatre.

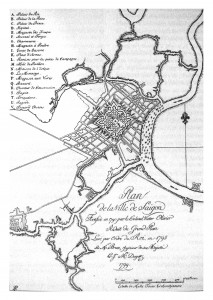

The arroyo Chinois (Bến Nghé creek)

How often, in Saigon, did I mingle with the crowd of Chinese workers who went every night to laugh at the heroic-comic scenes of these incomparable actors! The tiny puppet theatre, just four feet square, is located at a crossroads behind the Arroyo chinois [Bến Nghé creek]. Bamboo torches light the front of the small stage, and everywhere one smells coconut oil and the special odour of Chinese tobacco. No matter, I braved the disgusting smell! These puppets are much better and more finely made than ours; everything moves in them – legs, hands, head – and the fingers on the back of the hands even reverse, a feature which surprised me. It seems that many Chinese women can actually dislocate their fingers in this way.

The most common scenes in the repertoire were those of cheating spouses, battles and judgments, all presented in the alternately guttural and shrill voices of the Chinese players. The music accompanying the play, performed on flutes and squeaky stringed guitars, continuously repeated the same air, and when the action unravelled, vigorous drum strokes punctuated the insolent triumph of vice or the reward of virtue.

It was the day of a religious festival when I visited the other theatre, the one in which men (because the woman does not perform on the Chinese stage) usurp the place that should be taken by the puppets. Since representatives of the French authorities were present, along with many of the ladies of the colony, they toned down the usual crudity of the performance.

Behind the actors sat the musicians, while on both sides on the stage, resembling the marquises in the plays of Molière, strutted the rich Chinese traders who had paid for and hosted this entertainment. These gentlemen had carefully prepared beer, liquor and cigars, which were distributed profusely to all members of the audience.

Chinese opera performers

I took care not to attend the whole performance: it lasted about 10 hours! I only remember some episodes, including a very beautiful scene of spousal jealousy, and in particular a very well simulated fight between a troop of amazons and a genie armed with a short sword and a huge shield, under which it sometimes hid like a shell.

A hunting trip

From time to time, I went on hunting trips around Saigon, of which the most interesting took place in Pointat, game territory familiar to the Saigonnais. That day, at about 10am, as the sun got too hot, we went a pagoda surrounded by vast fields of pineapples, where our boy had prepared lunch. We were resting when two or three old men, with their white beards and emaciated cheeks, came in to worship the Buddha. At the sight of our liquor, their wrinkled old faces lit up with soft smiles and they stood behind us with envious admiration.

One of them offered me a cigarette, having previously smoked it a little in order to light it; I accepted, despite its betel-tinted end. In return, we offered them absinthe and vermouth; that’s what they had been waiting for, and they didn’t waste any more time praying before swallowing several glasses of liquor in quantities which would have left a European dead drunk. They, however, only became more expansive, and we held close company.

As we got up to leave, we heard the creaking of the wheels of a buffalo cart and we soon saw a huge vehicle advancing. It had large solid wheels, each made from a single piece of wood, and one of the old Annamite men told us that the noise made by these wheels had the effect of scaring tigers and other wild animals away. In many parts of the interior, this is the only means of transportation.

Cho-Quan Hospital

On another day, we went to visit the very handsome Cho-Quan Hospital; here they treat leprosy, one of the most dreadful diseases which is all too common in Indo-China. An interesting feature which can be noted is that leprosy never seems to strike Europeans; however, among the natives, it seems particularly tough on the Annamites, an essentially ichthyophage [fish-eating] people.

Chợ Quán Hospital

I saw one of these unfortunate people who had lost all the fingers of each hand, except his thumbs; his legs were swollen and bleeding, and his face was a mixture of deep grooves and hideous blisters. Another, a former temple guardian in Cholon who we named Quasimodo, suffered from a form of leprosy which had resulted in abnormal growth of the face, known as leontiasis; others had legs covered with so many ulcers that they were unable to walk. Besides leprosy, the Navy doctors of this hospital treat many skin diseases, which are very common in Cochin-China.

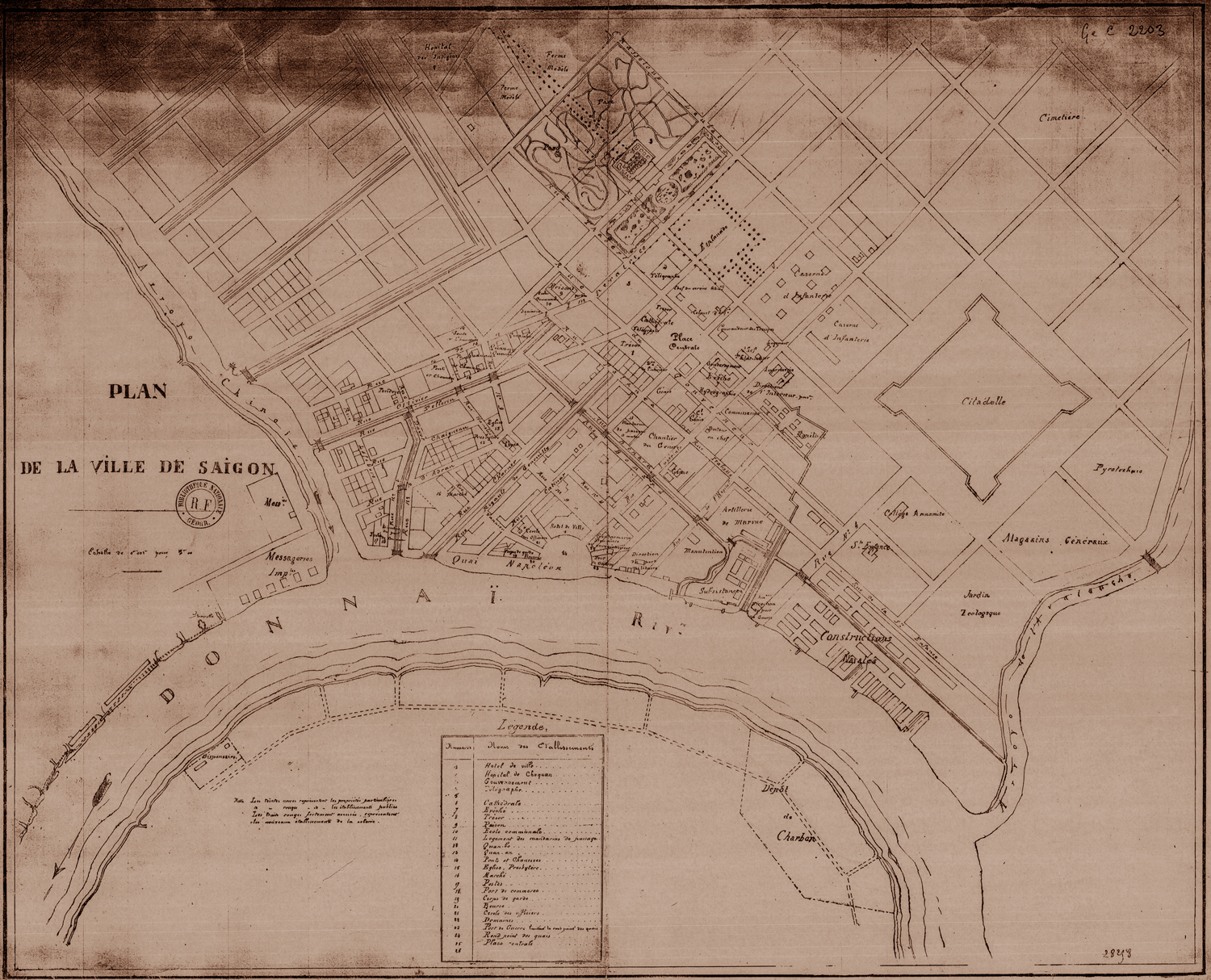

We lunched at Cho-Quan with colleagues, and after the obligatory nap in comfortable armchairs on the huge veranda of the hospital, we went to visit Cholon, from which we were about 3 kilometres distant. After Saigon, it is the largest town in the colony. Its population is about 80,000.

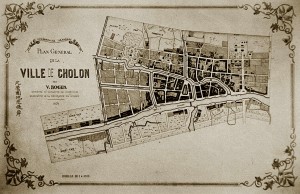

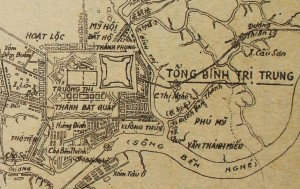

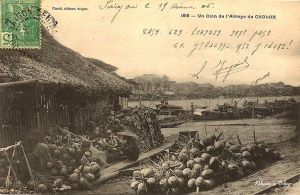

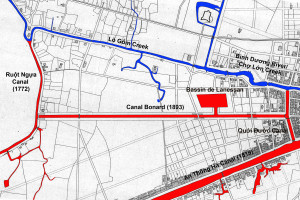

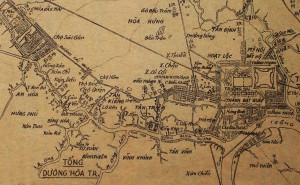

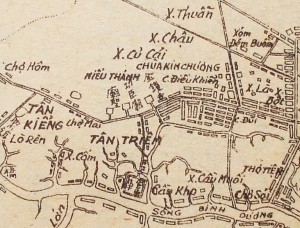

Cholon

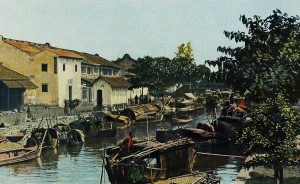

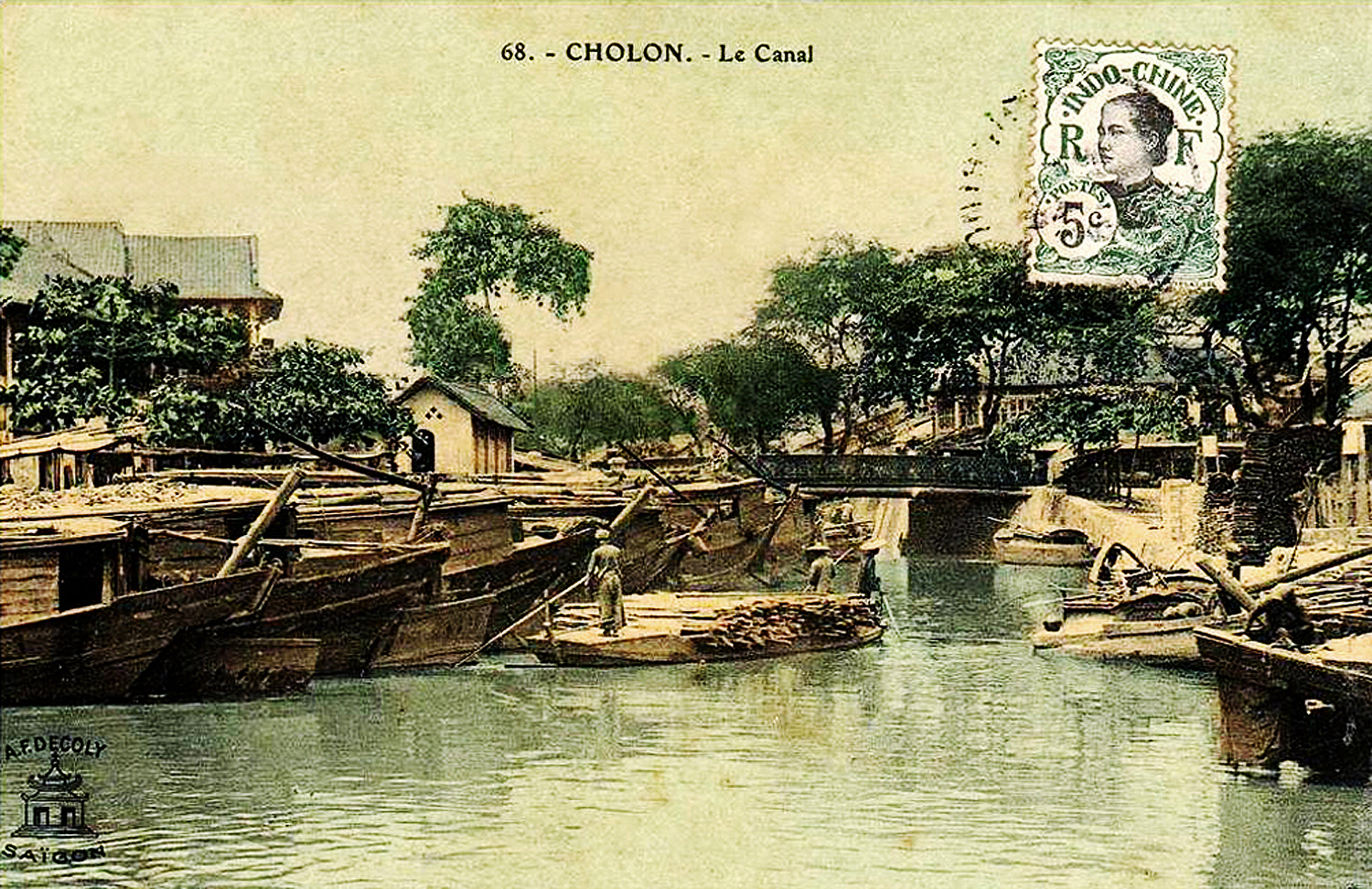

Cholon is separated from Saigon by a distance of 5½ kilometres, but linked to the European city by an uninterrupted row of villages, country houses owned by rich merchants of the “Celestial Empire,” and pagodas that serve as places of rest. Cholon is the centre of all Chinese trade in the colony. The amount of rice, fabrics and other Chinese products sold here exceeds the imagination; furthermore, the hustle and bustle in the streets, and the amount of Chinese and Annamite junks and sampans that fill the arroyo, are truly remarkable.

Among the features of Cholon which warrant particular mention are its crocodile parks. Along the banks of the arroyo, one finds a series of muddy enclosures, each measuring up to 20m² and flooded regularly by the high tide. Each of these enclosures is home to anything from 100 to 200 swarming crocodiles.

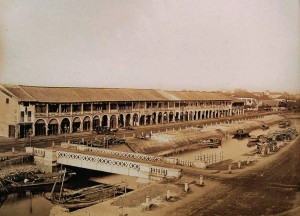

The quays in Chợ Lớn

When it becomes necessary to sacrifice one of these monsters for its meat, two stakes are raised, a noose is placed around the neck of the largest of the pack and it is pulled outside. The animal’s tail is held down, its legs are constrained and finally it is turned onto its back and tied with rattan. Another piece of rattan holds the jaws closed, and such is the strength of this plant that, despite the huge saurian’s prodigious strength, it cannot struggle and is killed without incident.

As for the flesh, though it is a little tough, it seems it has its value and is not impregnated with the smell of musk that so many travellers complain about. This meat is a very well received on the Annamite table.

After a three-month stay in Saigon, I must begin my wanderings through Indo-China.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.

![L0055713 Cochin China [Vietnam].](http://www.historicvietnam.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Plaine-des-tombeaux-by-John-Thomson-1867-Wellcome-Library-London.-Wellcome-Images-300x218.jpg)