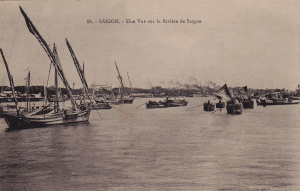

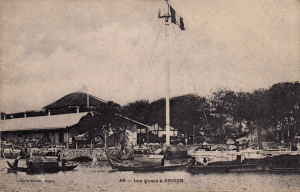

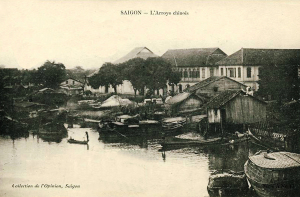

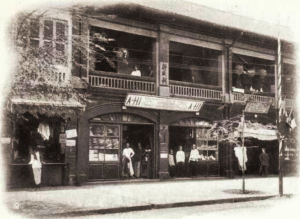

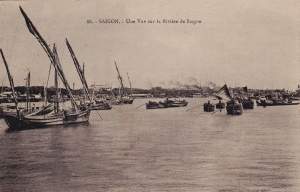

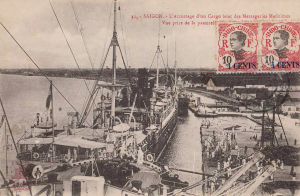

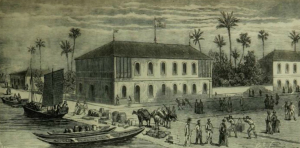

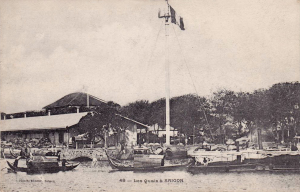

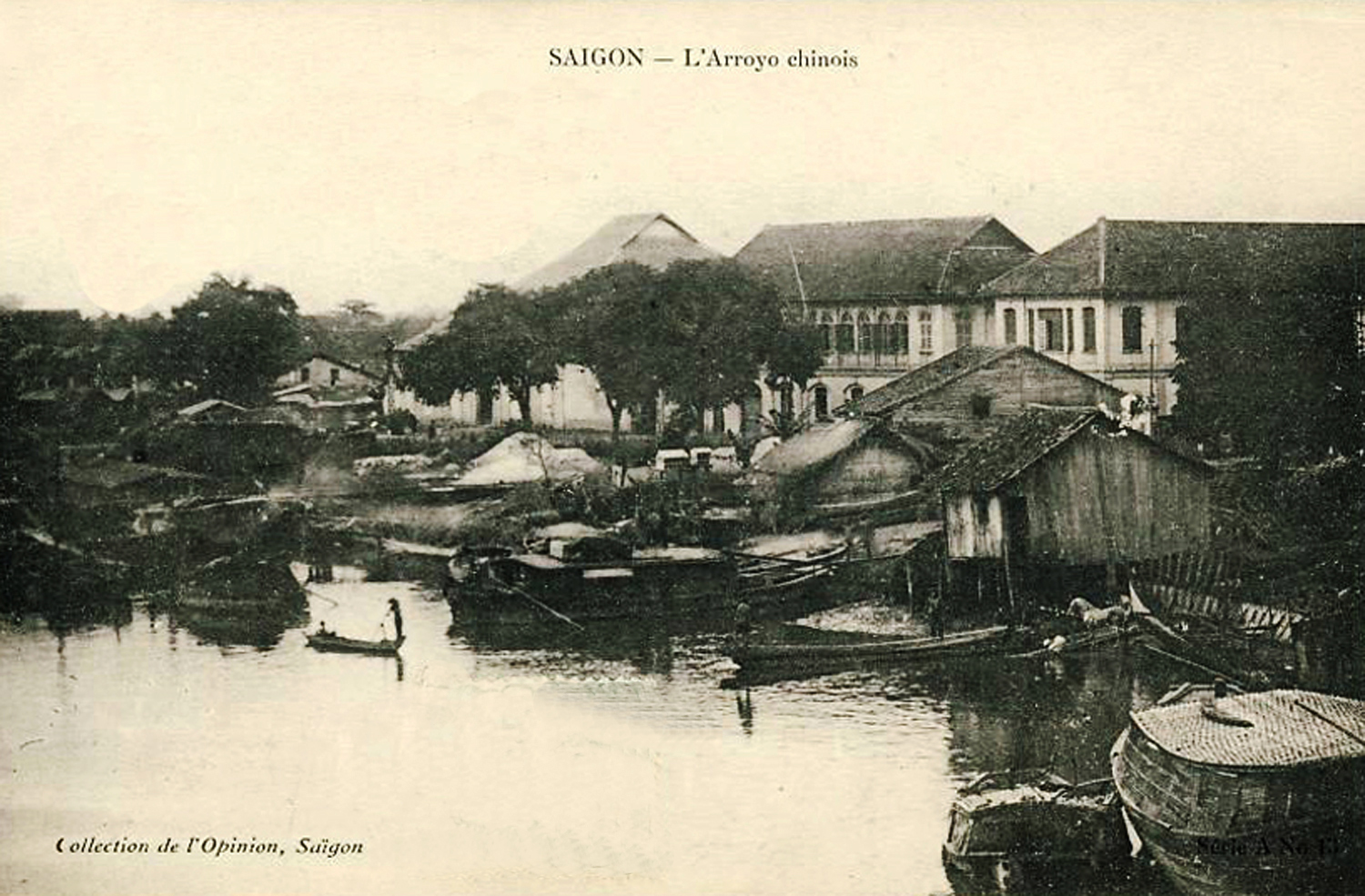

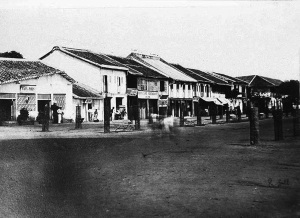

The “ville basse” or lower town viewed from the arroyo Chinois (Bến Nghé creek)

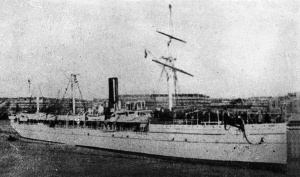

In March 1882, Arthur Delteil, retired Chief Pharmacist of the Navy, left Marseille on the Messageries maritimes vessel Oxus and travelled to Saigon, where he stayed for a year. This is the second of three translated excerpts from his book Un an de séjour en Cochinchine: guide du voyageur à Saïgon, published in 1887.

To read part 1 of this serialisation click here.

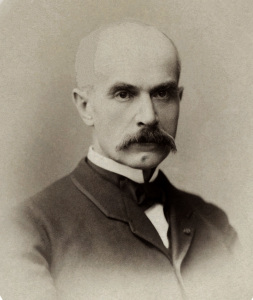

Cochinchina Governor Charles Le Myre de Villers (1879-1882)

The day after my arrival, I went to visit the Governor of the colony, M. Charles Le Myre de Villers [Governor of Cochinchina 1879-1882), who is now the Résident général in Madagascar. He received me and my fellow travellers with the utmost cordiality and invited us to join him for dinner the next day.

That first interview and the very frequent ones which followed have stayed with me, as M. Le Myre de Villers was one of the most welcoming governors I have ever known. I would therefore like to share my personal impressions of the man.

M. Le Myre de Villers carried out the high functions with which he was invested with great energy and dignity. Industrious, well-educated, familiar with all administrative and colonial questions, skilled in business, seeing and studying everything himself, and never resting unless strictly necessary, he devoted all of his strength and intelligence to the service of colony, which he sought to administer in a wise and progressive manner. Approachable and friendly to hard-working people, yet hard on the lazy and disorganised, this is how the man has been variously judged in the colony.

One may say that this civil governor was greatly loved by European officials of the Navy, by important traders and by the Annamites, criticised by some senior civil servants whose pretentions and jurisdictions he sought to diminish, and cordially hated by a small coterie of ambitious yet talentless people who raised their voice in quarrelsome opposition.

Charles Le Myre de Villers visiting a provincial centre in 1881

Physically, M. Le Myre de Villers was then a man of 50, tall, dark haired and lean, though of robust constitution. His stern demeanour, with strongly accentuated features and pale complexion, brought to mind that of Otto von Bismarck, with whom he shared a square face, broad forehead, black sunken eyes in a very pronounced brow, and strong black moustache covering the upper lip.

What dominated his whole person was an air of authority and decision-making which made one believe from the outset that this former sailor knew exactly what he wanted and was able to enforce his will with indomitable energy. His courage was up to all situations. When it involved stifling an insurrection fomented by the Chinese and Annamese in a distant province, he went there accompanied by just a single aide-de-camp. Finding himself suddenly in the midst of the rebels, he bravely arrested the instigators of revolt, and very soon everything returned to normal. His presence and moral lead sufficed to achieve this result.

On the occasion of the last cholera epidemic, which raged so cruelly amongst the Annamite class, how many times did I see the Governor himself enter the villages which had been infected by this scourge to visit the sick who had been abandoned by everyone else, reviving them with good words and distributing to these poor people all the relief and medicines that they needed! In instances such as this, nothing could stop him, neither the fear of sunstroke in a country where the sun can kill you as surely and sometimes as quickly as a gunshot, nor the prospect of a forced march through a filthy swamp.

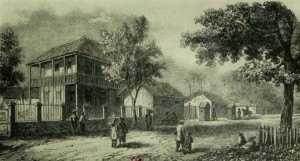

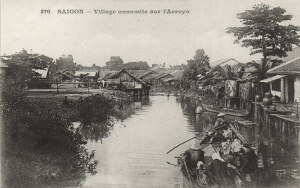

A village on the arroyo

He once said proudly that a colonial governor should be the first to place himself in danger, in order to set a good example to his officials and to the population; for only in this way would the Annamite people learn to love or at least to respect the nation that had conquered them.

M. Le Myre de Villers has often been described as a hardened authoritarian, yet this description of him is not quite accurate. He was a superior man of fixed opinions, who, for the successful completion of the work he had been commissioned to do, did not let himself be impressed by the clamour of a small clan of malcontents, nor by those who sought to impede improvements which were detrimental to their personal interests. In any case, isn’t every great man necessarily a little authoritarian? History tells us that. And in the last analysis, this Governor of Cochinchina was as good a diplomat and politician as he was a good administrator.

Only once did he fail to measure up to the task and was led to commit an act which in part caused his recall to France. Even in these circumstances, the metropolitan government supported him, because the initial damage did not come from his side, and it was felt that we should look twice before depriving such a large colony as Cochinchina, for such a trivial reason, of a Governor who had rendered such great services and was so appreciated. Attempts have since been made to remedy the injustice that was committed against him at that time, and he has recently been sent to La Réunion as Résident-general, a position which requires the utmost energy, capacity and patriotism.

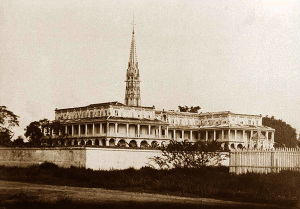

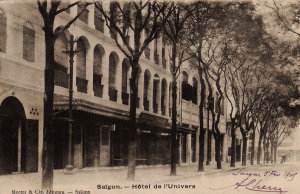

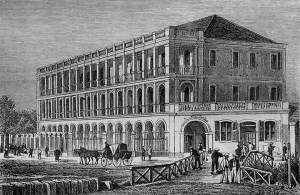

The Palace of the Government

M. Le Myre de Villers will, of course, be up to this task, and the Republic will not have to repent of having placed its trust in a man of such value. He will worthily represent France, forcing the Malagasy and foreigners to respect our protectorate and establish our influence in a country that we so often watered with our own blood, and from which our good friends the English would have us evicted.

In Saigon, the seat of his government, M. Le Myre de Villers had a simple way of receiving guests, which contrasted with the habits of his predecessors.

In the past, governors were content to give several grand formal dinners during the year to members of the Colonial Council, the main authority of the colony, but they rarely interacted with the “mere mortals” who were their constituents. However, M. Le Myre de Villers proceeded quite differently. He still received his Colonial Councillors in full regalia once or twice each year; but every evening he had at his table five or six guests chosen indiscriminately from amongst the civilian and military communities, ranging from simple sub-lieutenants and office clerks to generals and high administrators.

Here is how things usually went. One paid a first visit, which was always invariably followed by an invitation to return for dinner. So we went to the Palace of the Government in uniform or dressed in black. There, M. Le Myre de Villers, immaculately dressed in black coat and white tie and surrounded by his two aides-dc-camp, received us in the kindest way, with a hearty handshake.

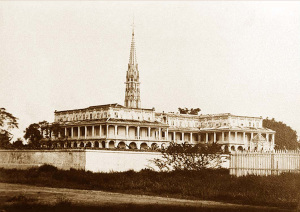

The front gate of the Palace of the Government on boulevard Norodom

At 7pm exactly, a maître d’hôtel came to inform the Governor that dinner was served and we went into the dining room. In the middle of the beautifully-prepared dinner table was spread a basket of flowers almost the size of a small flowerbed. Each diner was placed at table in order of precedence; this was one of the most difficult functions of the aides-de-camp. Dinner, without being excessive, was very delicate and worthy of the householder who received us.

The conversation was sometimes a bit cold, since some of the guests were not known to us, although the governor did his best to animate the conversation. But the essence of his character is very serious and he has little love for banalities, so that despite all the freedom of speech we enjoyed, everyone remained within the limits of respectful politeness.

After dinner we went into the events hall, which was decorated in a profusion of tropical plants, making it look almost like a greenhouse of colossal proportions. There were whist and écarté tables, and in the centre a large billiard table which was used to play cochonnet (a type of indoor boules), in which the governor excelled. He chose three willing opponents, and for half an hour he made windfall after windfall, soundly beating his novice companions in the art of this rather outmoded game.

The salle des fêtes (events hall) of the Palace of the Government

At 8pm, a dozen more people arrived to talk with the Governor. Like all great workers, he did not like to receive his staff in the daytime and waste his time in idle conversation. On the contrary, he reserved his evenings for all those who might have to speak to him. He devoted about 10 minutes to each person, talking in a playful and familiar way. Meanwhile, his dinner guests enjoyed greater freedom, playing card games, smoking and drinking cold beer which the Chinese servants brought frequently on trays.

At 10pm we took leave of the Governor; this was the time he set aside to plan new invitations for the following day.

We soon found that if we paid regular daytime visits to the Palace of the Government, we were pretty sure to be invited to dine there twice a month.

It was during these intimate evenings, in a relaxed environment and on “neutral ground,” that I was able to get to know the outstanding persons or notables of the colony.

General Louis Eugène Alleyron (1825-1891)

People like General Alleyron, Commander-in-Chief of Troops, a friendly but rather sickly old man who had been posted here after a glorious career in the service of his country.

M. Belliard, Director of the Interior, who on his own merit and through his strong work ethic had risen from the modest position of sub-officer to the eminent position he now occupied. He was a cold, uncommunicative man, with an iron constitution that had already withstood 15 years of residence in the colony.

M. Bert, Attorney General, head of the judiciary of the colony, a kind and well-educated man whom I had known previously in La Réunion.

Dr. Chastang, Chief Medical Officer of the Navy and one of my old colleagues. He was an energetic man and an informed and conscientious doctor, thoroughly acquainted with the diseases in this country.

M. Sergeant, Chief of the Navy’s Administration Service, the most charming, jolly and healthy-looking of all senior officials of the colony. Despite spending several years in Cochinchina, he had retained a magnificent appetite and a robust state of health on which the climate of Saigon seemed to have no effect.

M. Cornu, Mayor of Saigon, one of those men who are indispensible to the colony: honest, hard-working, respected by all, a man of boundless devotion to the interests of a town he has lived in almost since the conquest. He and his younger brother made their fortunes mainly from the rice trade and are now two of the city’s leading businessmen.

Colonial marine infantry officers

M. Denis, the representative of a large trading house from Bordeaux, who like the Cornu brothers enjoys a prestigious position and a great fortune honestly acquired from his large commercial interests.

It was at the Palace of the Government that I also made the acquaintance of M. Nortel, Inspector of Indigenous Affairs, and now Governor of New Caledonia; Colonel Bichot, who has since won his General’s stars thanks to his brilliant conduct in Tonkin; and M. Silvcstre, who rendered such brilliant services in Annam and Tonkin by organising the civil administration there.

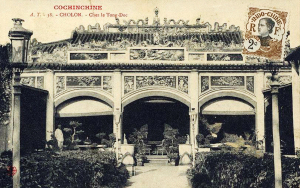

After completing my social duties, I formed a plan to visit the cities of Saigon and its neighbour Cholon. I will try to describe as quickly as possible the appearance of these two cities, their principal monuments and the most interesting places to see.

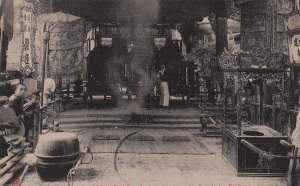

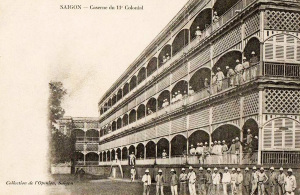

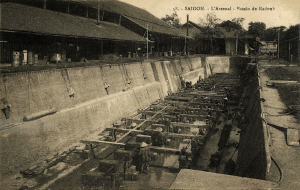

The present city of Saigon is scarcely 25 years old. When Vice Admiral Rigault de Genouilly seized Saigon on 17 February 1859, the Annamite city consisted of the citadel, the camp des Lettrés [the Trường Thi field where the triennial Mandarinate examinations were held] and some dirty and poorly-built huts scattered here and there in a mess that was far from being a work of art. Almost all of the area now occupied by the docks, the market, boulevard Bonard and the centre of the city was a vast swamp intersected by muddy arroyos.

It took the deployment of true creative genius to fill this swamp, firm the soil, dig sewers, create wide tree-lined boulevards with spacious squares and water fountains, and build elegant homes and remarkable monuments, in such a short period of time.

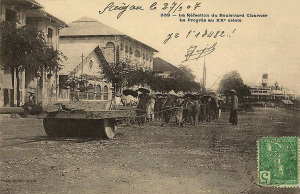

Surfacing boulevard Charner (Nguyễn Huệ boulevard)

To bring together all of these components and create a city which is partly oriental and partly European, elegant, beautiful, convenient to live in, full of life and movement and now occupied by a population of 35,000 souls.

It was the combined efforts of Admiral-Governors Rigault de Genouilly, Charner, Donnant, de la Grandière, Dupré and Duperré and Civil Governor Le Myre de Villers which brought about this rapid transformation. With their efforts, a muddy and filthy cesspool became one of the most beautiful and healthy cities of the Far East!

It took just 25 years to complete such a work, not to mention the civil, political, military and financial organisation of an entire colony of 2 million souls. Is this not a real tour de force?

I wonder if any of the nations who are considered the most skilled in colonisation would have achieved more or better in such a short time. The English, who think themselves more righteous than us in these matters, though jealous of our progress in Indochina, have repeated so often that we performed true wonders in Cochinchina in the few years that elapsed between our conquest and its definitive organisation. Sadly, there are still some French people who all too often like to disparage our work with a lightness and silliness that borders on a complete lack of patriotism.

Planting trees on the riverfront

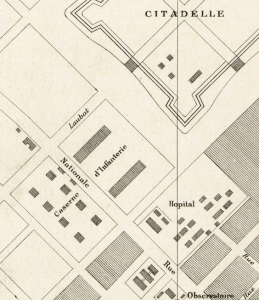

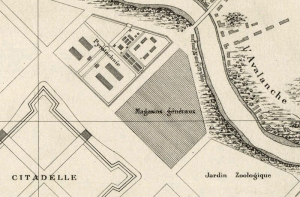

Taken as a whole, the city of Saigon is bounded to the north by the arroyo de l’Avalanche [Thị Nghè Creek] and the Saigon River; to the south by the arroyo Chinois [Thị Nghè Creek] and to the west by the vast sandy Plain of Tombs, so named because the Annamese have buried their dead there since time immemorial.

All of the streets are straight, wide, parallel to each other and connect with the quays which line the Saigon River and the arroyo Chinois. Many cut at right angles across other streets, forming spacious squares containing the busts or statues of admirals whose names are closely linked with the conquest or the grandeur of the colony.

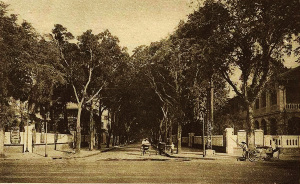

To provide shade for pedestrians, we had the good inspiration to plant double rows of trees – mainly tamarind, almond and teak – along most of our streets and boulevards. Intelligent sollicitude can never be excessive in a country where the sun is so hot and dangerous!

Now let’s follow a route through the city which will take us to the most interesting places to visit.

To read part 3 of this serialisation click here.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.