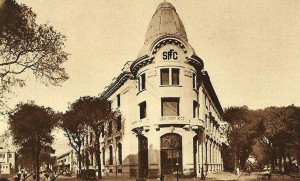

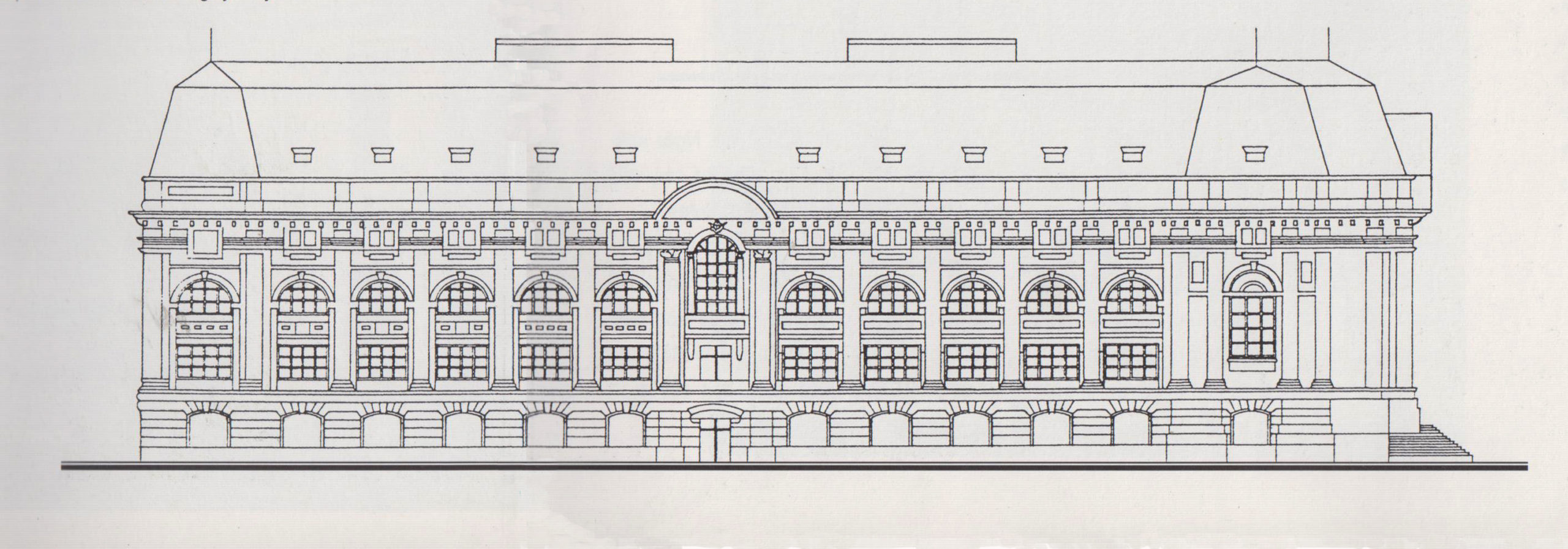

The main building of Bót Dây Thép

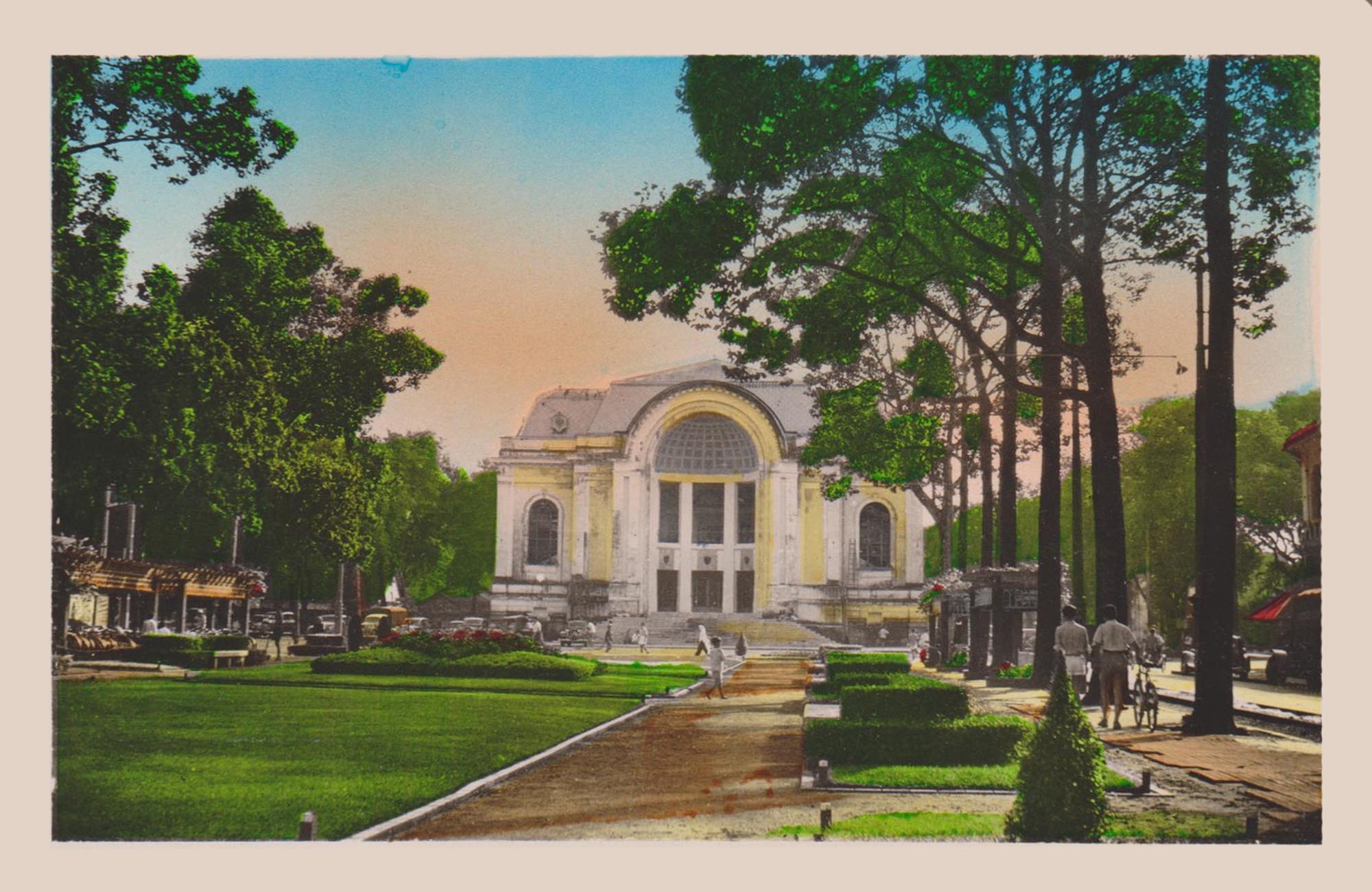

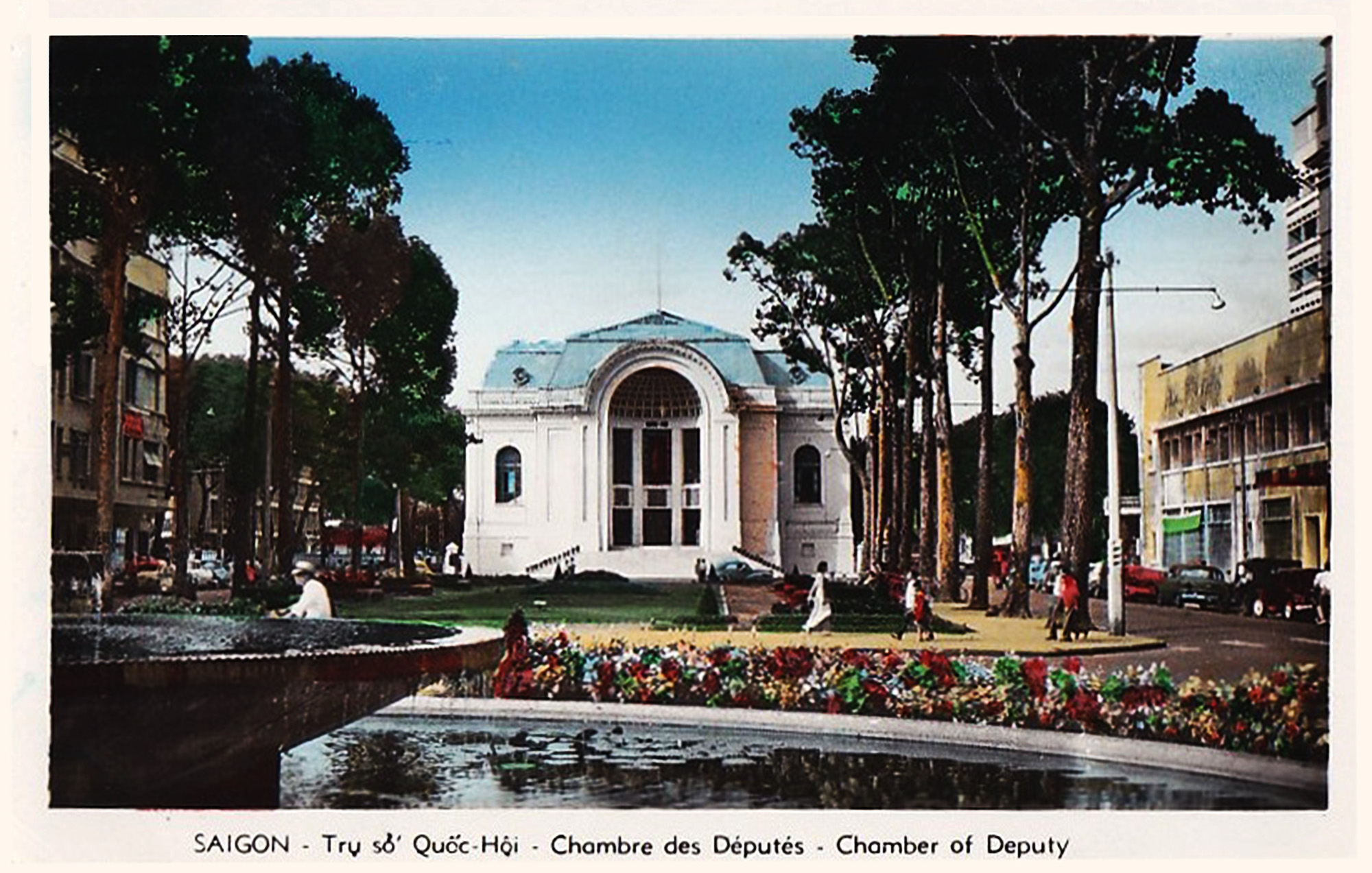

It’s surely only a matter of time before the Bót dây thép (“Steel Wire” Police Station), situated next to a main road in Hồ Chí Minh City’s District 9 east of Thủ Đức, joins the pantheon of so-called “dark tourism” destinations along with other infamous places of torture like the Medieval Crime Museum in Rothenburg, the Prison Gate Museum in The Hague and the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh.

Inside Bót Dây Thép

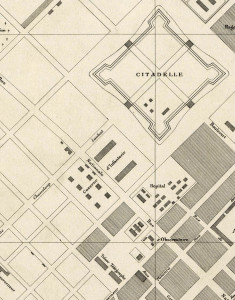

The complex originated in the 1920s as a French radio communications station, popularly known in Vietnamese as Nhà dây thép (literally “steel wire house”). The three 70m high steel antenna which once stood outside the complex have long since disappeared, but an old French water tower may still be seen near the entrance to the compound, which currently belongs to the District 9 People’s Committee.

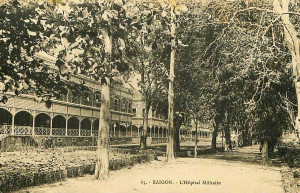

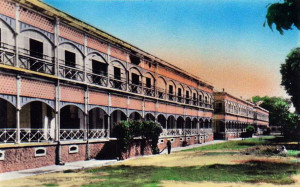

The main former police station building has been converted into a small museum, while its rear ground floor section is currently used as the District 9 Public Library.

The entrance to the temporary internment cellar

Bót dây thép was placed under the command of one Lieutenant Pirolet and his psychopathic deputy Ác râu (“Evil Beard”), who in 1946-1947 is said to have tortured and killed over 700 hundred Vietnamese political prisoners within its walls. The plaque outside the main building may be translated as follows:

After taking over the station in 1945, at the start of 1946 Lieutenant Pirolet transformed it into a police station which would bring horror to the people of Tăng Nhơn Phú and neighbouring districts.

The exterior of Bót dây thép

Under the authority of Pirolet and the bloodthirsty “Evil Beard,” the French set out every morning to the villages where they searched, pillaged and raped; they used barbed wire to bind together groups of innocent villagers, then they brought them back to the police station where they were imprisoned and subjected to various savage and barbarous tortures, turning this place into a hell on earth. They poured soapy water into the victims’ noses and mouths, hung them upside down from the ceiling and used red hot iron chopsticks to burn their bodies, hoping to find out about the activities of revolutionary soldiers. Though often tortured to death, the stubborn spirit of loyalty and steadfastness helped prisoners to remain silent to the last, making the French soldiers all the more furious because they could not achieve their objective. The bodies of the dead prisoners were decapitated and carried to Bến Nọc Bridge, where they were thrown into the river. Their severed heads were displayed on bamboo stakes outside the main gate of Bót dây thép to frighten the local community into submission. The remaining prisoners were then forced to lick the blood and eat the ears of the dead. Whoever refused to do this was also beheaded….

An ox cart used by the French to convey the decapitated bodies to the river for disposal

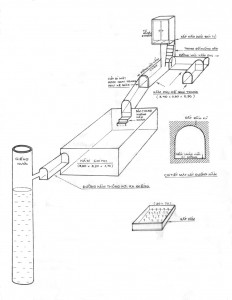

The main ground floor exhibition area incorporates a stairway which leads down into a small surviving section of the Hầm tạm giam (temporary internment cellar) and also displays a barrel used to hold the soapy water which was poured into the prisoners’ mouths and noses during interrogation sessions, a piece of wood (formerly part of a bed) used to hold prisoners’ heads in place so that “Evil Beard” could decapitate them, an ox cart used by the French to convey the decapitated bodies to the river for disposal and a boat used by local people to recover the bodies for burial.

The Special internment cellar

To the rear of the building is a small room which provides access to another former chamber of horrors, the Hầm biệt giam (Special internment cellar). The Vietnamese sign here reads:

This is a place in which the crimes of the French colonialists against the people of Tăng Nhơn Phú Ward and neighbouring areas have left a dark imprint.

A cover was installed over the cellar with a hole measuring 0.4m x 0.4m, just large enough for someone to be lowered in. Whenever they conducted interrogations, the French would lower the prisoners into this cellar with a rope lasso around their necks. Although the space below was very small, the French also held many people here at one time, in humid and putrid conditions, so that their bodies quickly became debilitated, then they were pulled up by ropes around their necks so that they could not breath.

The savage acts perpetrated by the French caused much tragic pain and injury to innocent people.

The upper floor of the building, which served from 1945 to 1947 as the main offices of the French police station, houses a meeting room and two small exhibition areas – one dedicated to District 9’s “Heroic Mothers” and the other to the victims of Pirolet and “Evil Beard.”

The final bas-relief on the wall of the Bến Nọc Memorial Temple shows Pirolet and “Evil Beard” being shot by revolutionary forces

Here visitors can see ropes, barbed wire and other items used to torture prisoners, spikes on which prisoners’ heads were impaled and personal details of many of the revolutionaries who died within the walls of the compound. This room also presents photographs, maps and artefacts outlining the anti-French revolutionary campaign conducted within the Thủ Đức area.

Around two kilometres east down the hill, next to the modern Bến Nọc Bridge, stands the Bến Nọc Memorial Temple (signposted Đền tưởng niệm Bến Nọc), erected in the 1990s in memory of the victims of Bót dây thép. The exterior walls of the temple are decorated with eight bas-reliefs which illustrate the entire story of the police station under Pirolet and “Evil Beard.” In the final panel we learn that they eventually got their come-uppance – both were killed by revolutionary forces during an attack on the compound.

Getting there

Address: Bót Dây Thép, Khu phố 2, Đường Lê Văn Việt, Phường Tăng Nhơn Phú A, Quận 9, Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh

Telephone: 84 (0) 8 3897 3064 (Mrs Thu Vân), 84 (0) 98 545 0654 (Mr Hưng)

Opening hours: On request 7.30am-11.30am, 2pm-5pm daily

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.