The second US Embassy building at 4 Thống Nhất (Lê Duẩn) in 1974 (photographer unknown)

As the international media descends on the city for the 40th anniversary of the fall of Saigon, travel companies report a growing demand from returning American veterans for tours which point out the buildings and installations they once occupied.

Over the past few weeks, tour companies in Hồ Chí Minh City have reported an ever-increasing number of requests by former US military and civilian personnel for bespoke city tours taking in the offices and bases in which they once worked.

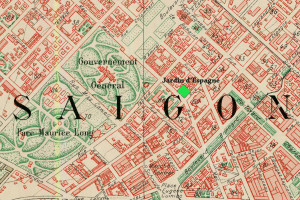

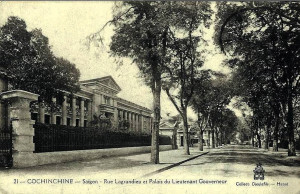

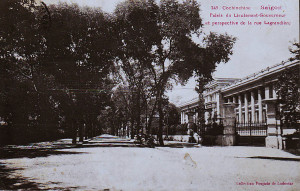

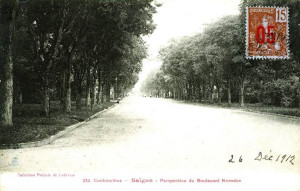

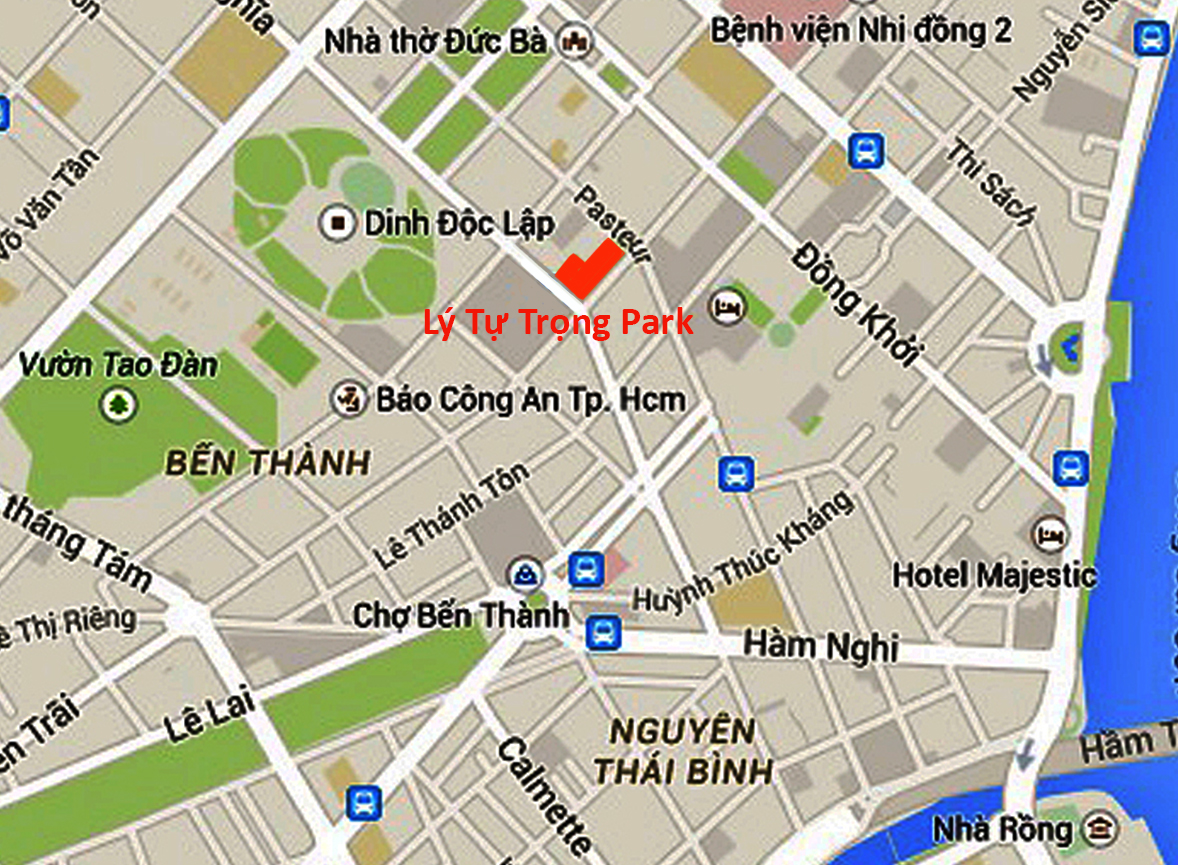

A typical starting point for most “US Vestiges tours” is a drive along Lê Duẩn (the former Thống Nhất) boulevard past the United States Consulate, which was built in 1998-1999 on the site of the historic 1967 American Embassy. In fact, the American diplomatic presence in Saigon may be traced back over 100 years, and several of the older US mission buildings still stand today.

The Catinat building at 26 Lý Tự Trọng, once home to an American Consulate which was car bombed by “Japanese gendarmerie” on 23 November 1941

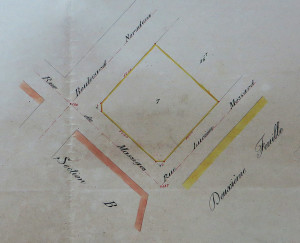

As early as 1907, a US Consulate could be found operating out of the old Denis Frères trading company headquarters at 4 rue Catinat (4 Đồng Khởi). Sadly, that old colonial edifice was demolished in 1985, but later US consulate buildings at 25 rue Taberd (25 Nguyễn Du, behind the Hotel Sofitel Saigon Plaza) and 26 rue de La Grandière (the Catinat building at 26 Lý Tự Trọng) may still be viewed today. On 23 November 1941, the latter became the target of a devastating bomb attack – said to have been perpetrated by “Japanese gendarmerie” – which caused extensive damage to the Catinat Building. Just over two weeks later, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and all US diplomats were expelled from Indochina. When the Americans returned in 1945, the US Consulate relocated yet again to 4 rue Guynemer (now 4 Hồ Tùng Mậu), before the opening of the first purpose-built US Embassy on boulevard de la Somme (Hàm Nghi boulevard) in 1950.

The first US Embassy building at 39 Hàm Nghi, bombed on 30 March 1965

The first US Embassy building at 39 Hàm Nghi was the model for the “American Legation” where CIA agent Alden Pyle worked in Graham Greene’s The Quiet American. On 30 March 1965, it became the target of another car bomb attack, this time by NLF Special Forces Team F21, which killed 22 and injured 183, prompting the relocation of the US Embassy in 1967 to a more secure location at 4 Thống Nhất (now Lê Duẩn) boulevard. Today, the building at 39 Hàm Nghi houses the Hồ Chí Minh City Banking University.

The second US Embassy building at 4 Thống Nhất (now the site of today’s US Consulate General at 4 Lê Duẩn) – a US$2.6 million fortress opened on 23 September 1967 – was famously breached in the early hours of 31 January 1968 by NLF Special Forces Team 11, as part of the wider Tết Offensive which involved attacks on over 100 towns and cities. A monument to this attack still stands today on the sidewalk outside the US Consulate compound.

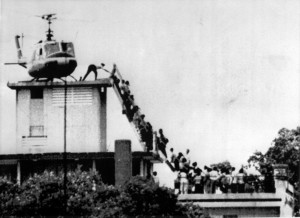

“Last day of Vietnam War: Evacuees mount a staircase to board an American helicopter near the American Embassy in Saigon” (Hubert van Es/AFP/Getty Images). Hubert van Es’s iconic image of people scrambling up a rooftop ladder to a helicopter at 22 Gia Long (now 22 Lý Tự Trọng)

Images of the second US Embassy were once more beamed around the world on 30 April 1975, when the destruction of the Tân Sơn Nhất Air Base runways by the approaching People’s Army obliged Ambassador Graham Martin to order a helicopter evacuation, and would-be escapees began thronging outside its gates trying to get in.

However, contrary to popular belief, the iconic image by Dutch photographer Hubert van Es of people scrambling up a rooftop ladder to a helicopter was taken not of the Embassy, but rather of the CIA’s “Pittman Apartments” at 22 Gia Long (now 22 Lý Tự Trọng).

Apart from the locations of former consulates and embassies, other extant former US installations in Hồ Chí Minh City include the headquarters buildings of the Military Assistance Command Việt Nam (MACV or “Macvee”) and its predecessor, the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG).

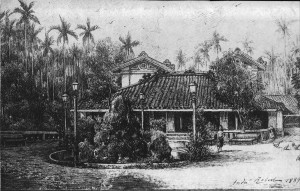

The former SAMIPIC villa at 606 Trần Hưng Đạo, which served successively as MAAG, MACV and Korean Forces HQ

Before 1962, the US military advisory effort in Việt Nam was co-ordinated by MAAG, which initially occupied the former SAMIPIC villa at 606 Trần Hưng Đạo in District 5. In February 1962, following the arrival of the first US Army aviation units, MAAG became part of the Military Assistance Command Việt Nam (MACV), which was set up to provide a more integrated command structure with full responsibility for all US military activities and operations in Việt Nam. MAAG survived until May 1964, when its functions were fully integrated into MACV. In May 1962, when MACV relocated to larger premises, the villa at 606 Trần Hưng Đạo became known as MACV II. Then in 1966, following the transfer of MACV operations to Tân Sơn Nhất Air Base, it was vacated by the Americans and became the headquarters of Republic of Korea Forces Vietnam, which remained there until the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1973. Today, 606 Trần Hưng Đạo is home to a number of local businesses, but the old villa is currently under threat of redevelopment – see Date with the Wrecker’s Ball: 606 Trần Hưng Đạo. UPDATE – This building was demolished in August 2018

The second MACV headquarters at 137 Pasteur

The second MACV headquarters in Saigon – an unassuming three-storey apartment building at 137 Pasteur in District 3 – has an interesting history. Before being taken over by the US military in May 1962, it served from 1955 to 1959 as the headquarters of the Michigan State University Group (MSUG), which was controversially engaged to advise President Ngô Đình Diệm on the reorganisation of his feared secret police. By 1966, MACV had outgrown this building too, so on 2 July 1966 it was relocated to the new purpose-built “Pentagon East” complex, adjacent to Tân Sơn Nhất Air Base. Between 1966 and 1972, 137 Pasteur functioned as the headquarters of the MACV’s Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG), a special operations unit tasked with covert warfare operations. When the last active-service US military units departed in 1972, all MACV operations in the south, including MACV-SOG, were subsumed within the Defense Attaché’s Office (DAO), a branch of the US Embassy. In the following year all DAO operations were transferred to the “Pentagon East” complex and 137 Pasteur was returned to civilian use.

The former Dodge City Bachelor Enlisted Quarters (BEQ) and a surviving building of the MACV Annex near Tân Sơn Nhất International Airport

Nothing now remains of the huge “Pentagon East” complex, which was formerly situated on the east side of modern Trường Sơn boulevard (the Tân Sơn Nhất International Airport approach road), between the Cửu Long and Hồng Hà street junctions. In its place today stand the CT Plaza Tân Sơn Nhất shopping mall and cinema complex, and next to it a very large building site. However, on nearby Hồng Hà street, visitors can still see the former Dodge City Bachelor Enlisted Quarters (BEQ) and one surviving building of the MACV Annex, both currently used by the Southern Airport Services Company (SASCO). UPDATE – The MACV Annex building was demolished in 2015.

In addition to the former MAAG and MACV buildings, the Saigon residences of the US generals who ran these two organisations have also survived intact.

The villa at 60 Võ Văn Tần (known before 1975 as 60 Trần Quý Cáp) in District 3 is said to have been built originally for a wealthy French wine importer, but it was later acquired by Prince Nguyễn Phúc Ưng Thi (1913-2001), founder of Vikimco Steel, who also built the Rex Hotel. In the late 1950s, he made the villa available to the United States of America to house its military commanders-in-chief.

The MACV chiefs’ villa at 60 Võ Văn Tần

Thereafter it became the residence of two consecutive MAAG Chiefs – Lieutenant General Samuel T Williams (November 1955-September 1960) and Lieutenant General Lionel C McGarr (September 1960-July 1962). In 1962, when MAAG was integrated into MACV, the head of MAAG was found new lodgings at 121 Trương Định (see below), while 60 Trần Quý Cáp became home to successive MACV Chiefs, including General Paul D Harkins (February 1962-June 1964), General William C Westmoreland (June 1964-July 1968), Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, Commander of Naval Forces Việt Nam and Chief of the MACV Naval Advisory Group (July 1968-1970), General Creighton Abrams (1970-June 1972) and latterly General Frederick C Weyand (June 1972-March 1973).

After MACV took over the mansion at 60 Võ Văn Tần/Trần Quý Cáp, the last MAAG Chief, Major General Charles J Timmes (July 1962-May 1964) was rehoused in another grand old colonial pile, just up the road at 121 Trương Định. Originally constructed as a managerial residence for the Diethelm import-export company, this building is now in poor condition, but it is still in use as the Hoa Mai Kindergarten (Trường mầm non Hoa Mai).

The former at US Naval Support Activity Saigon (NSAS) building at 218 Nguyễn Đình Chiểu

Midway between those two former residences, on the east side of the Trương Định/Nguyễn Đình Chiểu street junction, stands another relic of the US presence. In the late 1960s, the down-at-heel apartment building at 218 Nguyễn Đình Chiểu (formerly 218 Phan Đình Phùng) briefly functioned as the headquarters of US Naval Support Activity Saigon (NSAS). Unfortunately its close neighbour, the former Naval Forces Việt Nam (NAVFORV) building at 117 Nguyễn Đình Chiểu, didn’t fare quite so well – it was demolished a few years back to make way for a luxury apartment block.

At the outset, the United States devoted considerable resources to information and culture programs in South Việt Nam, and by the late 1950s the United States Information Service (USIS) Saigon office was one of the largest posts of its kind in the world. From 1956 to 1962, USIS Saigon was housed in the large grey building designed by modernist architect Arthur Kruze which still stands on the eastern corner of the Hai Bà Trưng/Lý Tự Trọng intersection, originally 82 Hai Bà Trưng but now designated as 37 Lý Tự Trọng.

The former USIS building at 37 Lý Tự Trọng

According to an American report of 1956, “The USIS occupies excellent, roomy quarters in three floors of a street corner building at a prime location in downtown Saigon, about a mile from the Embassy. It is completely air-conditioned. The facilities include a library (ground floor); 150-seat auditorium; radio studios; and film editing and recording rooms. The square footage totals 33,454.”

In 1962, the USIS expanded its operations, moving its administrative offices and Abraham Lincoln Library into the new Rex complex and transforming the building at 82 Hai Bà Trưng into an annex.

Built by Prince Nguyễn Phúc Ưng Thi (see above) in 1959, the Rex Hotel Complex at 141 Nguyễn Huệ was snapped up on completion by the American government. Down to 1964, it not only housed the USIS offices and Abraham Lincoln Library, but also provided hotel accommodation for many US military advisers. During this period it was also home to the first broadcasting studio of Armed Forces Radio Vietnam (AFRVN), which went on air for the first time at 6am on 15 August 1962. Two years later, AFRVN was found larger facilities at the nearby Brink Bachelor Officers’ Quarters (BOQ, see below).

The Rex Hotel

As the insurgency got under way and it became clear that US culture and information programs had failed to win widespread support for the Ngô Đình Diệm regime, the United States began to switch to a primarily military strategy. By 1964, the Abraham Lincoln Library had been relocated to a quiet villa at 8 Lê Quý Đôn (demolished in 2010), and in the following year, as the first US combat troops set foot on Vietnamese soil, the USIS operation at the Rex was subsumed into the Joint US Public Affairs Office (JUSPAO, also incorporating the Communications Media Division of USAID Việt Nam). The annex at 82 Hai Bà Trưng was then redesignated “JUSPAO 2.” Meanwhile the Rex Hotel became a BOQ for US military personnel.

At its height in the late 1960s, the Rex complex had around 600 employees and was frequented regularly by over 450 international journalists covering the US war effort.

The Caravelle Hotel

Between 1965 and 1972, JUSPAO and the MACV Information Office jointly hosted daily press briefings for foreign correspondents, which became known as the “Five O’Clock Follies” because, according to one cynical reporter, “they seldom bore any resemblance to the facts in the field.” Initially held in a 200-seat conference room on the ground floor of the Rex, these press briefings were moved in 1969 to the National Press Center building at 15 Lê Lợi (since redeveloped as the Opera View complex) opposite the Caravelle.

During the same period, the Caravelle Hotel, also opened in 1959, became the hostelry of choice for the US media. By the late 1960s it was home to the Saigon bureaux of numerous American news agencies, including NBC, ABC, CBS, the Washington Post and the New York Times, while its rooftop bar (now Saigon Saigon Bar) famously became an unofficial “press club” to which journalists such as Walter Cronkite, Neil Sheehan and Peter Arnett would retreat in the evenings.

A monument outside the Park Hyatt Hotel commemorates the car bombing of the Brink residence by NLF Special Forces on Christmas Eve 1964

The Park Hyatt Saigon Hotel, located behind the Municipal Theatre, also stands on a site of historical interest. An earlier hotel, constructed on this site in the late 1950s, was acquired by the American military and later transformed into the Brink BOQ at 103 Hai Bà Trưng. A residential block for US army officers with its own mess hall and in-house bakery, Brink also became home to the studios of AFRVN from 1964 to 1967. While the BOQ building no longer exists today, a monument on the corner outside the Park Hyatt Hotel commemorates the car bombing of the Brink residence by NLF Special Forces on Christmas Eve 1964, an event which killed two and injured around 60. The Brink BOQ and its radio station were subsequently repaired, and it was from here in 1965-1966 that the real Adrian Cronauer – immortalised by Robin Williams in the Hollywood film “Good Morning, Vietnam!” – broadcast his radio programmes to American troops.

The Kỳ Hoà Hotel at 238 Ba Tháng Hai in District 10, once the headquarters of the Free World Military Assistance Organization (FWMAO)

The Kỳ Hoà Hotel at 238 Ba Tháng Hai (formerly 12 Trần Quốc Toản) in District 10 is another building with a fascinating story to tell. In the 1960s and early 1970s, it served as the headquarters of the Free World Military Assistance Organization (FWMAO), which housed the various country liaison offices for allied operations during the Việt Nam War. In addition to co-ordinating the activities of military personnel sent to Việt Nam by Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, the Philippines and Thailand, FWMAO also managed the flow of non-military (medical, transportation, construction, agriculture) support by a variety of other nations. All of the “Free World Forces” received logistical support and operational guidance from the United States Military Assistance Command Việt Nam (MACV).

For foreigners who lived and worked here before 1975, the streets of Saigon remain a treasure trove of faded reminders of the American presence – from the old USAID buildings at District 1’s Cách mạng Tháng 8 and Nguyễn Khắc Nhu streets and District 3’s Ngô Thời Nhiệm street, to the former Pershing Field Ball Park (now the Military Zone 7 Stadium) near Tân Sơn Nhất International Airport, the so-called “Thieves’ Market” on Tôn Thất Đàm street and the numerous former BOQ and BEQ buildings dotted all over the city.

Many veterans have spent years trying to forget the horror and futility of the Việt Nam War, but tour guides report that those who have made the effort to return have found great solace in seeing for themselves just how much the country and its people have recovered and grown in the intervening years.

You may also be interested to read these articles:

American War Vestiges in Saigon – 60 Vo Van Tan

American War Vestiges in Saigon – 606 Tran Hung Dao

American War Vestiges in Saigon – 137 Pasteur

American War Vestiges in Saigon – Former “Free World” HQ

American War Vestiges in Saigon – Former USIS Headquarters

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

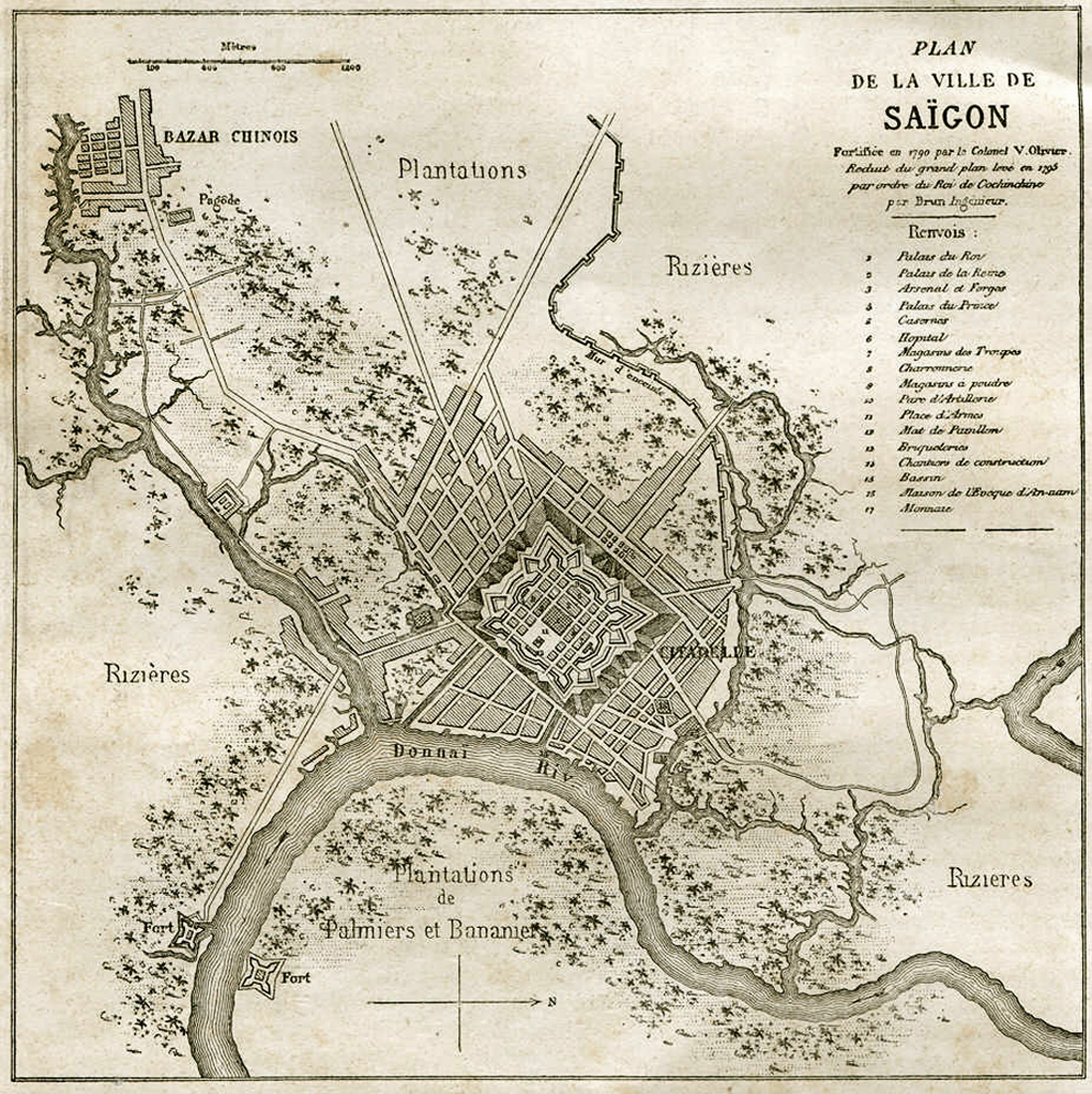

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.