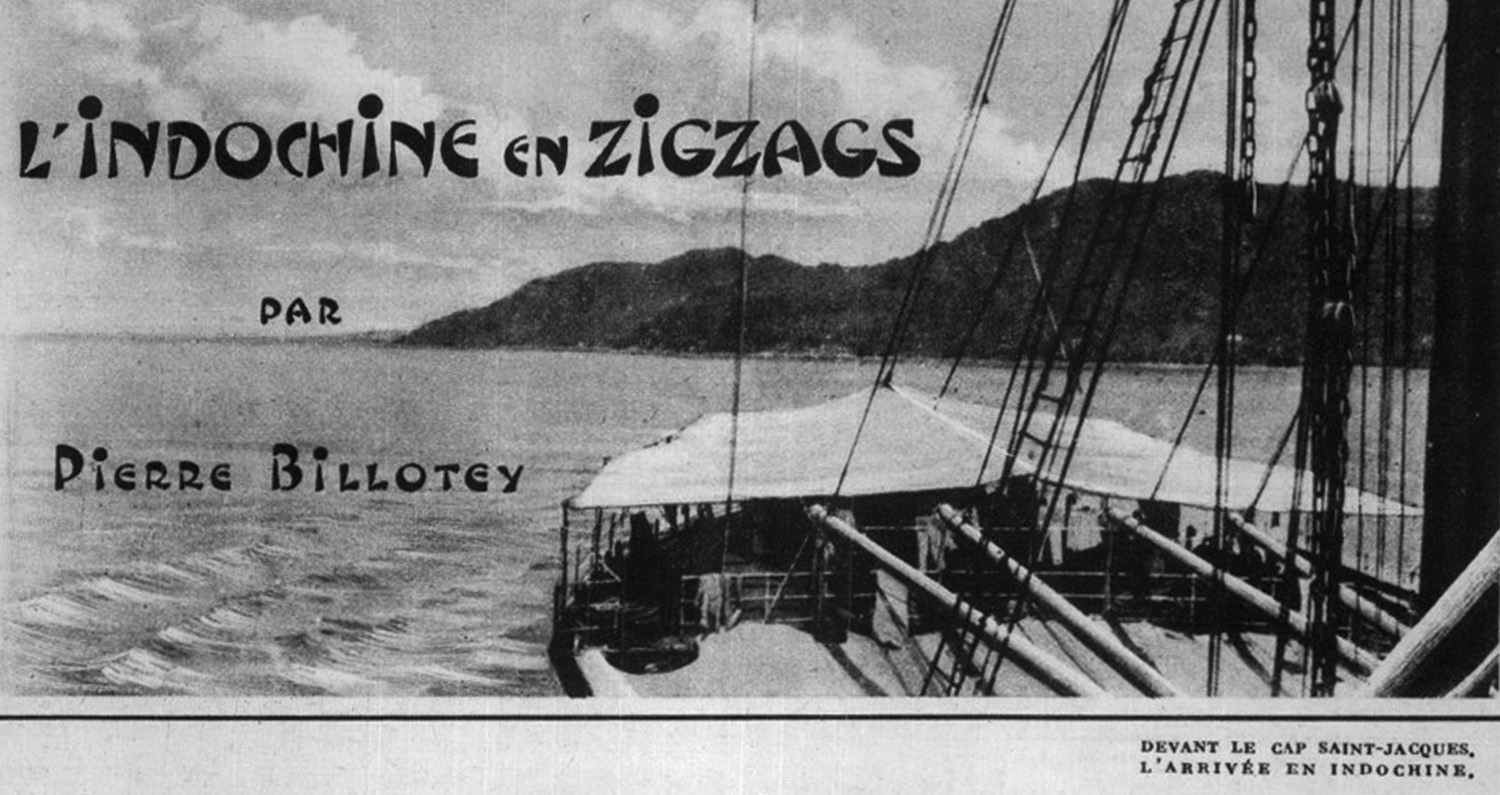

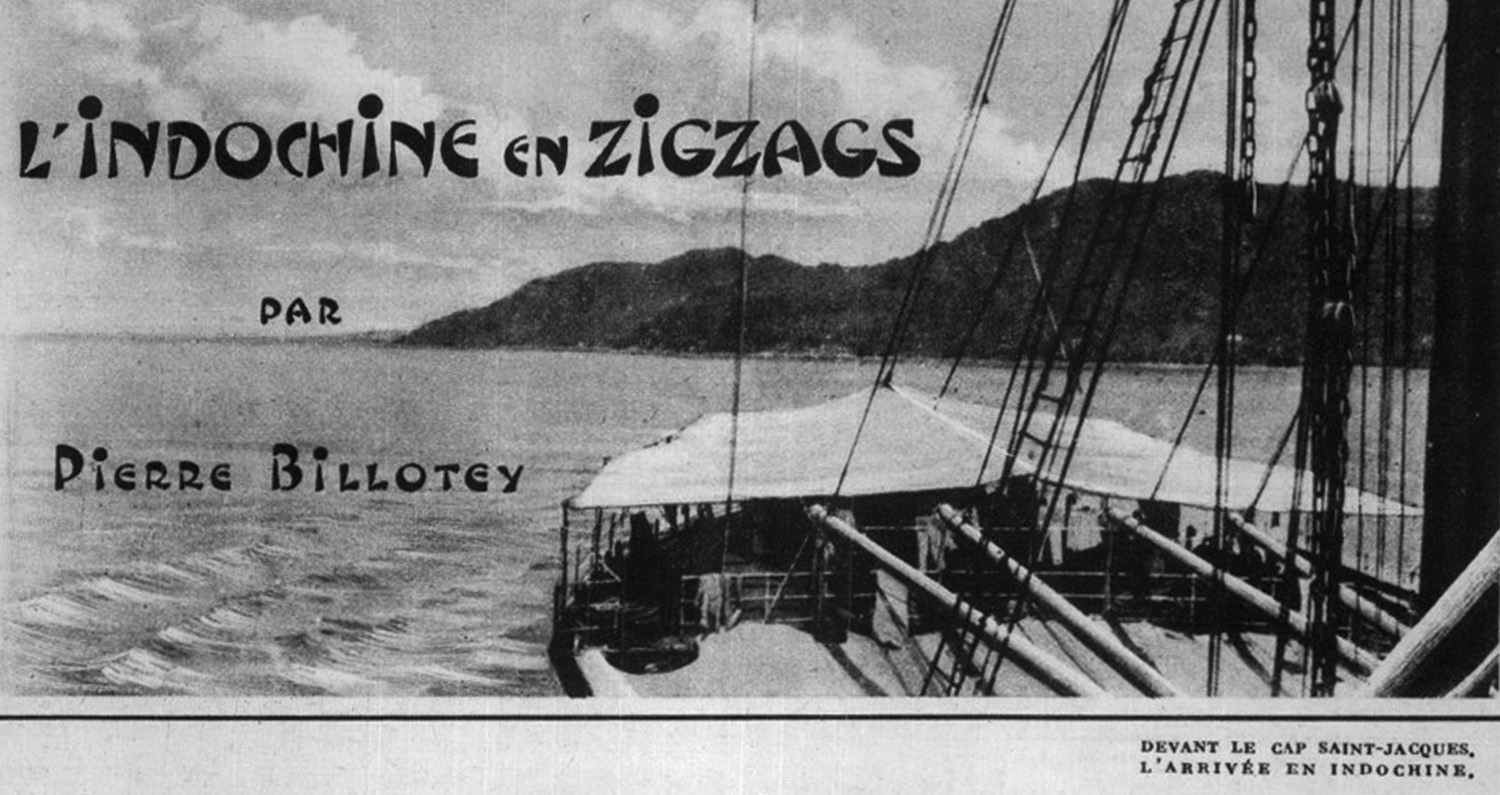

After touring Southeast Asia in 1927-1928, French novelist Pierre Billotey (1886-1936) was inspired to write his most famous novel, Sao Keo. But he also penned a series of articles entitled “Indochina in Zigzags” for the monthly review Les Annales politiques et littéraires, describing his travels in Indochina. Here is a translated excerpt describing Billotey’s visits to Saigon and Đa Lạt.

Cap Saint-Jacques beach with fishermen

Our ship comes to a standstill off the coast of Cap Saint-Jacques [Vũng Tàu], a mountainous promontory with a lighthouse on top of one of its three peaks. The flag is hoisted as we wait for the tide so that we can enter the Saigon River which leads into Indochina…

The water is a thick and green, like absinthe or even pureed peas. On either side, there is nothing but low plain. Each bank supports a thin line of black soil in which sprout the brilliant but monotonous mangroves.

Here and there, we see fishing junks moored. Several of them, standing near the shore in front of native huts, are decorated with French tricolour flags. Why? This is almost certainly a wedding. The native people of Cochinchina have the habit of marrying under French colours!

The river narrows and begins to turn yellow as it negotiates a bend. Behind our ship, we leave long golden waves in which green and purple reflections of the sky shine in concentric ovals, creating what look like huge peacock feathers. Proceeding with the flow of the current, we pass through the little islands of Loc-Binh, which are surrounded by floating plants with beautiful blue flowers and leaves almost similar to those of our lilies. This Loc-Binh is, however, a scourge for navigation: it often paralyses the propellers of the most powerful steamships.

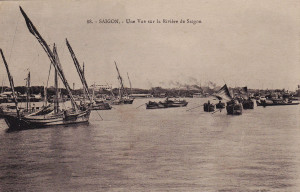

A view of the Saigon river

Now, only mangroves and short palm trees border the shoreline. Beyond them spread the endless expanse that we take, in early October when the rainy season ends, for splendid pastures. No, these are the rice fields of Cochinchina, which we view under the vivid light – I would even call it Italian light – of late afternoon. Meanwhile, next to the soft, clean earth, the river, now crowded with sampans and junks, draws ever more complicated curves.

Then suddenly, amidst the purple smoke of the city, we see the two towers of Saigon Cathedral rising in the distance.

When one has spent nearly a month travelling from sea to sea, feeling the growing distance from one’s native land and gradually coming to the realisation that most of the world is ruled by the English kingdom, this sudden glimpse of the spires of a French cathedral makes a very great impression indeed.

The ship has docked. Night descends. Insects whirl around the electric lights which illuminate the bridge. Not without farewell, nor without emotion, I disembark after four weeks of travel. We certainly had the time to get used to it. I soon miss the quiet and comfortable life on board that great ocean liner of the Chargeurs Réunis, which, even in a storm, hardly rocked more than a riverboat on the Seine.

A few minutes later, I am walking in the rue Catinat: France rediscovered!

La rue Catinat

Yes, Saigon is a great and beautiful French city, set in lush tropical greenery. I wasn’t expecting anything like this. Many of the descriptions I’d read or heard were spoiled by a superfluous and sometimes ridiculous exoticism.

Here on the rue Catinat, the shops are lined up almost in unbroken sequence. They include those selling European products, as well as those of the Malabar (Hindus of French India, settled in large numbers in Indochina), the Chinese and the native Annamites. Elsewhere, especially in the huge area known as “le Plateau,” one sees villas and public buildings, all surrounded by flame trees, bamboo thickets and palm trees of every kind. And what flowers – whole clusters of gorgeous roses and liane antigone, baskets of orange canna lilies, splashes of scarlet hibiscus and climbing bougainvillea, a thousand purple petals crowded against each other in gigantic bouquets.

It’s not very long ago (1859) that the conquerors, the admirals who created Saigon and Cochinchina, found nothing here but a vast swamp intersected by arroyos with houses on stilts. Thereupon they plotted the city. The arroyos were filled to create today’s beautiful and vibrant avenues, the boulevards Charner, Bonnard and Galliéni, as well as boulevard Norodom, which is somewhat reminiscent of our avenue du Bois. But the trees here are far more grandiose than those back home. Tamarinds, teak, mango and many others, always green.

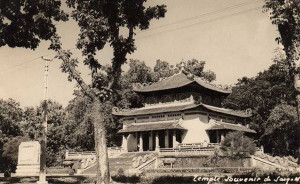

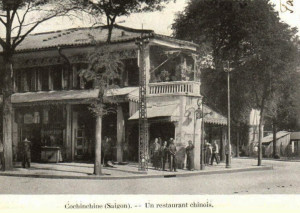

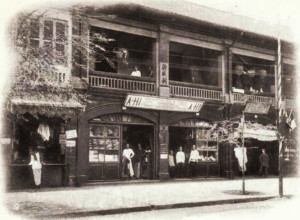

Saigon – a Chinese restaurant

After having visited all those British colonial cities, with their rectangular buildings, so ugly in their weighty pride, and their pleasant but isolated and selfish bungalows, what a delightful impression Saigon makes – offering visitors a real welcome and a glimpse of genuine civilisation – urbanity and urbanism!

And what animation we see! We pass Chinese men wearing white trousers, Annamites in black jackets which gleam like oilcloth, and Malabars wearing turbans, or more often red or white caps, and enrobed from head to foot in garish patterned fabric. All of them, without exception, walk barefoot. Yes, even the native pousse-pousse (rickshaw) driver. The shoe trade would certainly not prosper here! Also barefoot are the pretty rich Annamite women who wait outside the stores for their luxury automobiles.

The cars! How many there are! Most of the French settlers have one. A number of Chinese and natives also own automobiles. And the pousses-pousses! Here in Saigon there is an entire population of rickshaw drivers, each sporting a towel or headband and a conical hat over his eyes, dressed sometimes in basic shorts and sometimes wearing a coat. He runs along at a frenetic pace, dodging large vehicles and occasionally shouting a faint cry to warn passers-by to get out of the way.

Le Grand Hôtel de la Rotonde (Neurdein/Roger Viollet/Getty Images)

While he waits expectantly outside places like the Grand Hôtel de la Rotonde, hoping for a customer, one may observe the pousse-pousse driver closely, squatting oddly on the curb between the two bamboo poles of his lightweight carriage, watching with a keen eye the Europeans he surmises are nearly ready to leave their restaurant tables. There is nothing more delightful than to take a journey in one of these vehicles. Remember that they are equipped with pneumatic tyres. These, of course, sometimes burst. Then we see the driver with his head bent low, slowly and sadly taking his vehicle to be fixed.

Do not complain too much about the hard life of the rickshaw drivers. They make a pretty good living. And the humanitarian philosopher who speaks of getting rid of this trade would have them to answer to.

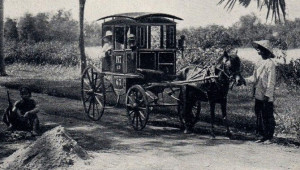

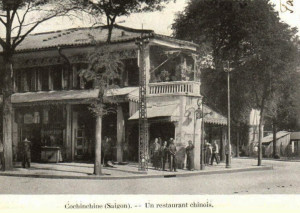

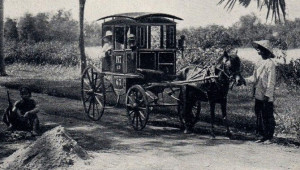

From time to time, amidst the flood of automobiles and pousses-pousses, one also sees carts pulled by two tiny oxen, or the occasional Malabar, that baroque box of painted wood suspended on four wheels, which is very reminiscent of our coaches of yore.

Saigon – a “Malabar” in the Botanic Gardens

French people promenade through the streets wearing white or grey canvas suits, followed by half-naked domestics and native administrative staff whose dress is very often more elegant than one’s own. Then come Annamite women wearing long flowing black silk tunic and trouser suits and carrying children on their hips. This particular Saigon street, especially after sunset, offers a continuous and very entertaining show!

Right in front of one’s eyes, in the course of just one minute, it is possible to see anything up to a hundred different and contrasting sights, which blend perfectly together to give the viewer an impression of harmony, difficult to define, yet strongly felt. Here one will find all the charm of the French city – or large provincial town, if you will – under an East Asian sky, together with all the splendour of wonderful tropical vegetation, and the amazing variety of races which live here.

Through the windows of my apartment, round like large portholes, I take in the green lawns, red soil driveways, beautiful palm trees and clumps of bamboo which stand at least 20m high. However, by now a storm is raging, and in this season it’s a daily occurrence. A double rainbow may be seen amidst dark clouds, from behind which lightning flashes everywhere.

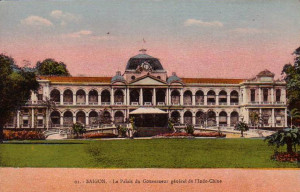

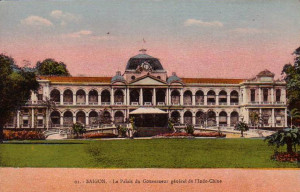

The Palace of the Government

Right in the middle of this “Parc-Monceau of the tropics” stands the imposing and graceful Palace of the Governor General. It constitutes, of course, the best of Indochina’s colonial architecture. I love its large porches, lofty halls and two long galleries which overlook the city. Here one may really believe oneself to be on the deck of a large ocean liner.

It is in a pleasant wing of this castle that I am housed during the few days before my departure for Hanoi and Upper Tonkin, China perhaps, and especially for that mysterious Laos, so little known here and which I have been told is very difficult to access.

During my first hours in Saigon, I meet my friend and colleague MH, who was formerly the editor of a Paris newspaper, and now runs one of the largest papers in Indochina. It is with this very fine and knowledgeable observer that I first tour Saigon, its harbour and walks, shops, new buildings and smokey factories, ending up at an automobile garage so vast and so well equipped that one might have difficulty finding a similar facility back home, even in Paris.

“Huh!” Says my guide at every step, “didn’t you expect to see this?”

“Well, no. Saigon is really a very modern city.”

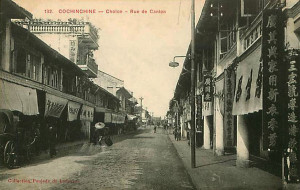

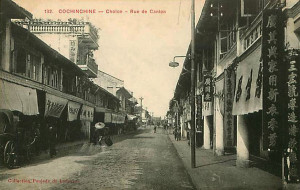

Cholon – rue de Canton

“When Lord Northcliffe arrived here, he was as surprised as you are, and yet he’d just completed a round-the-world tour. He wrote that there could never be enough praise for a creation like Saigon which was developed so quickly and so happily.”

I walk through Cholon with MH on several occasions, day and night. Who doesn’t know about this Chinese city, the nearby annex of Saigon, since Roland Dorgelès spoke so well of it? But perhaps Dorgelès, who once judged Loti to be too poetic, was also guilty of poeticising Cholon? This commercial town is mainly populated by Chinese, sympathetic, always smiling, gentle and dignified, and who, if they are not all good people, at least know how to give the impression that they are.

Cholon is clean, Cholon does not smell bad, Cholon is not truly Chinese. You just need to wander through the fetid alleys of Singapore, with their hovels of humid rotten filth, to measure the difference, to understand that our Cholon is almost Frenchified. Above all, it is a large industrial and mercantile city. And its traffic, which passes through the port of Saigon, contributes in no small way to making the latter France’s sixth most important port, just below Rouen.

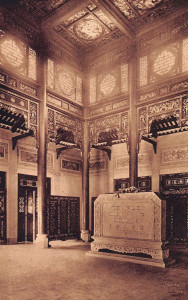

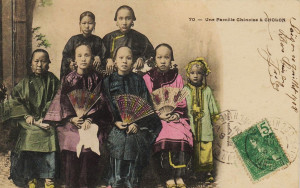

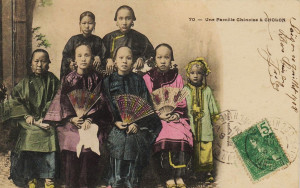

A Chinese family in Cholon

It is not that Cholon has no secret life, or disturbing and bizarre legends. But let us be silent on those. Let’s permit Cholon to keep its last mysteries. You Chinese princes of paddy, I will not denounce your saturnalia…..

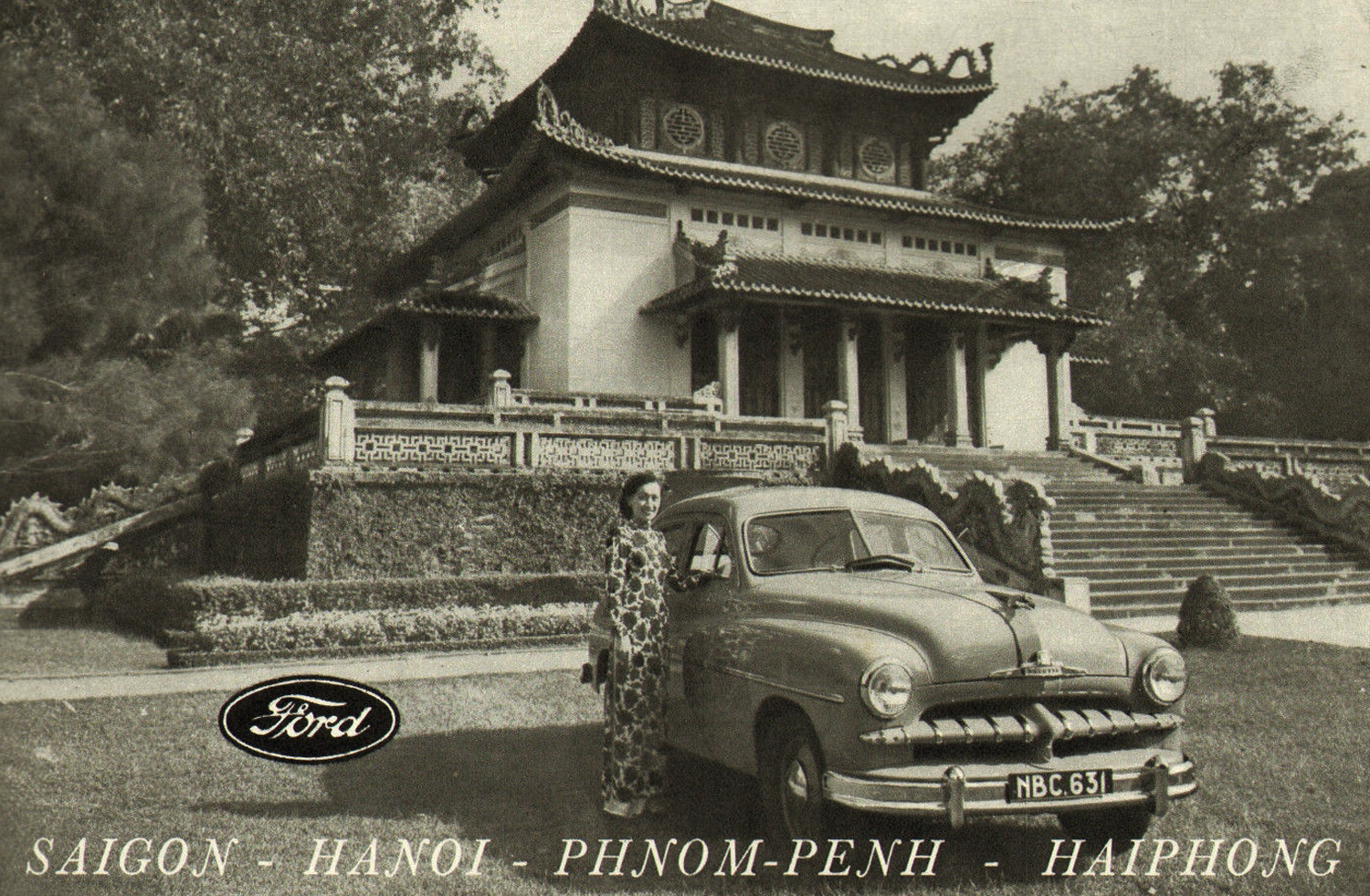

Time to leave. Before me I have a 1,800km road between Saigon and Hanoi. This is nothing. This does not count, since many others have followed this road before me. The government has lent me an excellent car with a proficient driver. Thus, with just myself and the spectacle, what an admirable promenade I will take through Annam and up to Tonkin!

But the day before I leave, I am introduced a very amiable man who had landed a few hours earlier, and also wishes go to Hanoi.

“Look,” he tells me, “You can see that I’m not fat, so I won’t take up much room. And don’t you think that for such a long trip it would be better that you don’t travel alone?”

He adds that he knows some of my family, and, hand on heart, he swears that travelling with me will be an unforgettable pleasure for him.

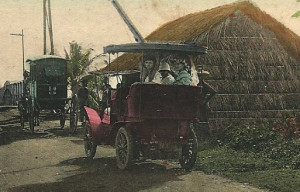

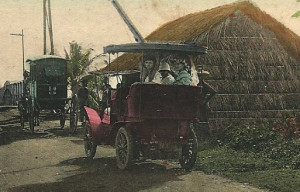

Setting off for the north

About himself, he gives me a few details. In a Gascon accent, he tells me that he is a Basquaise named Sigognac.

“And I am,” he finishes with gravity, “an artist of great talent.”

It doesn’t take me long to decide. The next morning I send the car to get him. But when it comes back, I begin to think that I will have to give up my seat altogether. The astute Sigognac has completely filled the back of the car with suitcases, those of his charming cousin and himself. Thanking the gods, I manage to find a seat in front, next to the driver.

From that trip, what I remember most are the Annamite villages, the first I’d ever encountered. All of them the same, or nearly so – whitewashed, single-storey houses and thatched huts.

But the most essential thing to see is the multitude of beautiful covered markets which the administration has built everywhere for the native people. The Annamites meet, buy, sell, eat and talk there at any time, day and night. They are so many of them! Some sleep while the others chatter. And then they swap places. What a noise!

Collecting rubber sap

The other day, sailing up the river to Saigon, I contemplated the immense rice fields, which constitute the main wealth of Cochinchina. Now, as we head north, there appear the rubber plantations, the second most important fortune of this country. Line after line of rubber trees stretch into the distance until they are no longer in sight. On each trunk hangs a wooden bowl flowing with latex – this is the nascent rubber which pays the interest on so many shares. Sometimes, one catches sight of a worker going down the aisles, emptying the wooden bowls into a bucket.

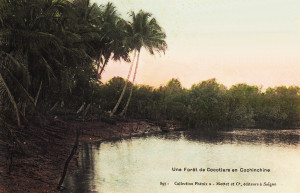

And, now we find ourselves in the great forest. The trees have fluted trunks which look like cathedral pillars and are of the same stone grey colour, while their layered canopies reach prodigious heights. Bamboos bow and bend, forming bridges across the road, while any gaps are filled so perfectly by creepers and other vegetation that all one can see either side of the road are two sparkling green mountains, so dense that the undergrowth is completely hidden.

This is the forest of South Annam, which every now and then gives way to a clearing. I’m sure I was told that it’s home to gaurs – Asian aurochs – as well as elephants, rhinos, leopards and tigers. But I see only doves … and then a large lizard basking in the middle of the road, which amusingly nods its flat and pointed head at us.

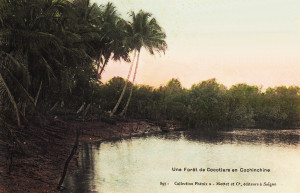

A forest of coconut trees in Cochinchine

And what rivers! Before each river crossing, a prudent and charitable sign warns us:

“Attention: Hazardous Bridge.” The bridge boards, not nailed down, bounce up and down under the wheels of our automobile, making a noise like castanets. We negotiate 14 or 15 bridges like this, in quick succession. However, it seems that they are not that dangerous, since none of them collapses under our weight.

Suddenly the trees disappear. To our left, in the far distance, we see violet-tinted mountains, silhouetted against the pale cobalt sky. And then we arrive in Phan-Thiet.

I had been told the day before: “Phan-Thiet? It’s of no interest.” Yet Phan-Thiet interests me. Firstly for its swarming Annamite population. And secondly because it is a port.

Large and yellow, the river which runs through the town before reaching the sea is covered right up to its mouth by hundreds and hundreds of large fishing junks, grey in colour, each with one or two masts and decorated sails. These vessels also line the seashore, where they are parked alongside the sandy beach. A little above the town, small boats, sampans, rattle against each other.

Fishing boats in Phan-Thiet harbour

When night falls, I notice that the central living quarters of each boat has a copper lamp which illuminates the tiny space where a whole family is accommodated.

One invisible yet very striking thing marks out the character of Phan-Thiet. It’s the frighteningly nauseous smell which spreads across the town from the nuoc-mam factory installed there. This Annamite national condiment, appreciated by few Europeans, is a kind of essence of fish – rotten fish, say those who do not like this strange product. It is the latter whom one must one warn in advance to wear nostril plugs before walking through this town…

Early next day we leave Phan-Thiet. Sigognac has left his largest bags there. Turning our back to the coast, we advance again, and soon find ourselves once more in the middle of boundless jungle.

This time, the road begins to climb the mountain, rising through masses of rock and earth, the colour of the latter ranging from Venetian red to the most intense purple. In front of us, the road forms a scar through the bright green forest.

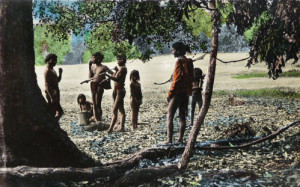

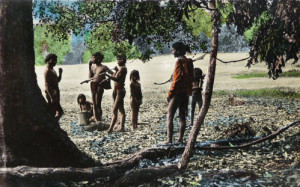

A montagnard family in the central highlands

Frequently bordering a precipice, the road continues to climb, twisting its way through huge trees, those trees which cannot be named, and which, when compared to ours, seem like giants to little children. High on a branch, parrots chatter. As we pass, birds of enamel blue, green pigeons and grey doves take flight.

On several occasions we pass montagnards, walking in small groups. To all intents and purposes they are naked – because a simple string tied around the waist to support a square of cloth like the tiniest of handkerchiefs can hardly be described as clothing. Most of the women do not even wear that – they wear nothing at all, just a basket on their back.

The men, these creatures of prehistory, walk in single file, spears in hand, bows on their shoulder. Since Phan-Thiet, we seem to have gone back in time six thousand years.

Later, speaking to me of the region’s montagnards, someone told me:

“They aren’t wicked, these montagnard hunters. If they hate the Annamites, they have their reasons. With us, they get along very well. They only ask that we respect their customs and their women.”

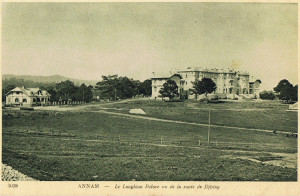

The Lang Bian mountains

“How?” I mused,“They are jealous of their women, and yet they let them walk around like that?”

The forest, always the forest… Sometimes, on the side of a peak, one sees a group of bamboo huts on stilts, with lofts of straw or woven reeds. These are montagnard villages, enclosed by palisades. All around, buffalo with black ringed horns are grazing.

Soon, those strange tropical trees disappear. Beyond a certain altitude, one encounters only pine trees, as majestic as those of our Pyrenees.

But in France, the pine forests have something sad, almost deathly about them. And they remain silent, the soil around them covered only with a layer of dead needles. Here, in contrast, vegetation abounds between the scaly pine trunks. High clusters of red flowers bloom in the bushes. And the forest is alive with wildlife. Birds flutter, monkeys scream, branches stir without one knowing what agitated them. Nearby, a torrent runs down the hill. Further on, it becomes a waterfall as it meets a precipice and plunges into an abyss.

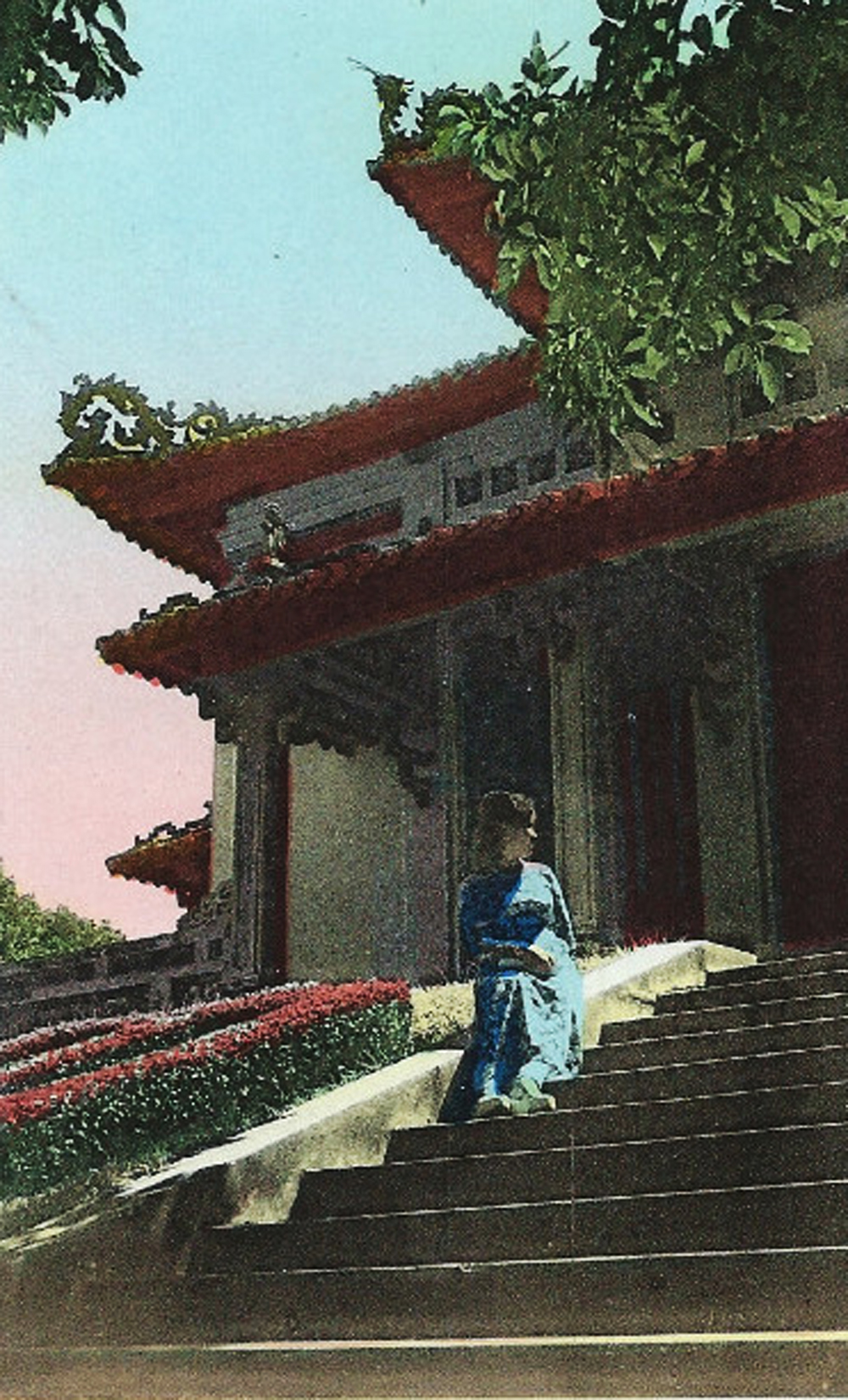

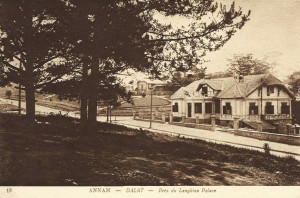

Dalat

We’ve arrived in Dalat, the famous and much lauded Dalat. After the splendours we sighted on the journey, all new for me, this city of nascent waters, with its palace, its villas, its lake, and its plateau enclosed to the west by the peaks of Lang Bian, leaves me feeling indifferent. I’ve already seen this, or nearly so, in Font-Romeu or Savoie…

However, we must remember that Dalat is a most precious hill station where Europeans – especially women and children – who are anaemic and sometimes almost wiped out by the excruciating heat and humidity of Cochinchina and the coast of Annam, come to regain their health in the cool and crisp air.

But what surprises the traveller most is not feeling the cold after having been so hot. Rather, it is the striking contrast in scenery. For hours and hours, one has climbed through high forest and wild mountain, meeting naked hunters armed with stone-age spears and bows with poisoned arrows. Then suddenly, the road arrives at a palace worthy of Cannes or Biarritz, where black-coated domestics serve lunch in an ultramodern dining room.

The Langbian Palace Hotel, Dalat

“Whether you like it or not,” says the director of this palace, “Dalat will one day be the capital of the Indochinese Union. Is it not madness to have chosen Hanoi, so far from the centre and so close to China?”

Hearing this makes me smile. But later, in Hanoi, I would hear one of the highest officials of the colony say much the same thing. And then I would not smile. For I would see in that comment the sign and the desire for capitulation, for the abandonment of a once grand design. When a governor, in 1902, had decided that Hanoi would be the capital, when he undertook the construction of that great thing which we now call the Yunnan Railway, it was because he then believed, beyond any doubt, that Yunnan would sooner or later be part of Indochina.

My companion Sigognac interrupts the conversation. Pointing to the walls, he suggests that they would be more attractive to the eyes if they were covered with large decorative paintings, executed with great skill, just like those which he, Sigognac, considers himself capable of producing.

“There is no rush to decorate the walls,” replies the director. “But wait (at this juncture, he turns to look outside), can you see that bare rocky outcrop? If you could paint that white for me, it may give my guests the impression of snow…”

Dalat viewed from the Langbian Palace Hotel

The real surprise for me, arriving in Dalat, is not finding a growing town 1,500m above sea level, amidst a savage country, far from everything, nor – I’m ashamed to say – the admirable efforts which have created everything I see here.

No, after travelling so many leagues across a forest so grand that it becomes overwhelming, what makes me suddenly so pleased is to discover a delicate and unexpected thing: beautiful pink roses, fragrant and in full flower.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebooks Exploring Huế (2018), Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (2019) and Exploring Quảng Nam (2020), published by Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.