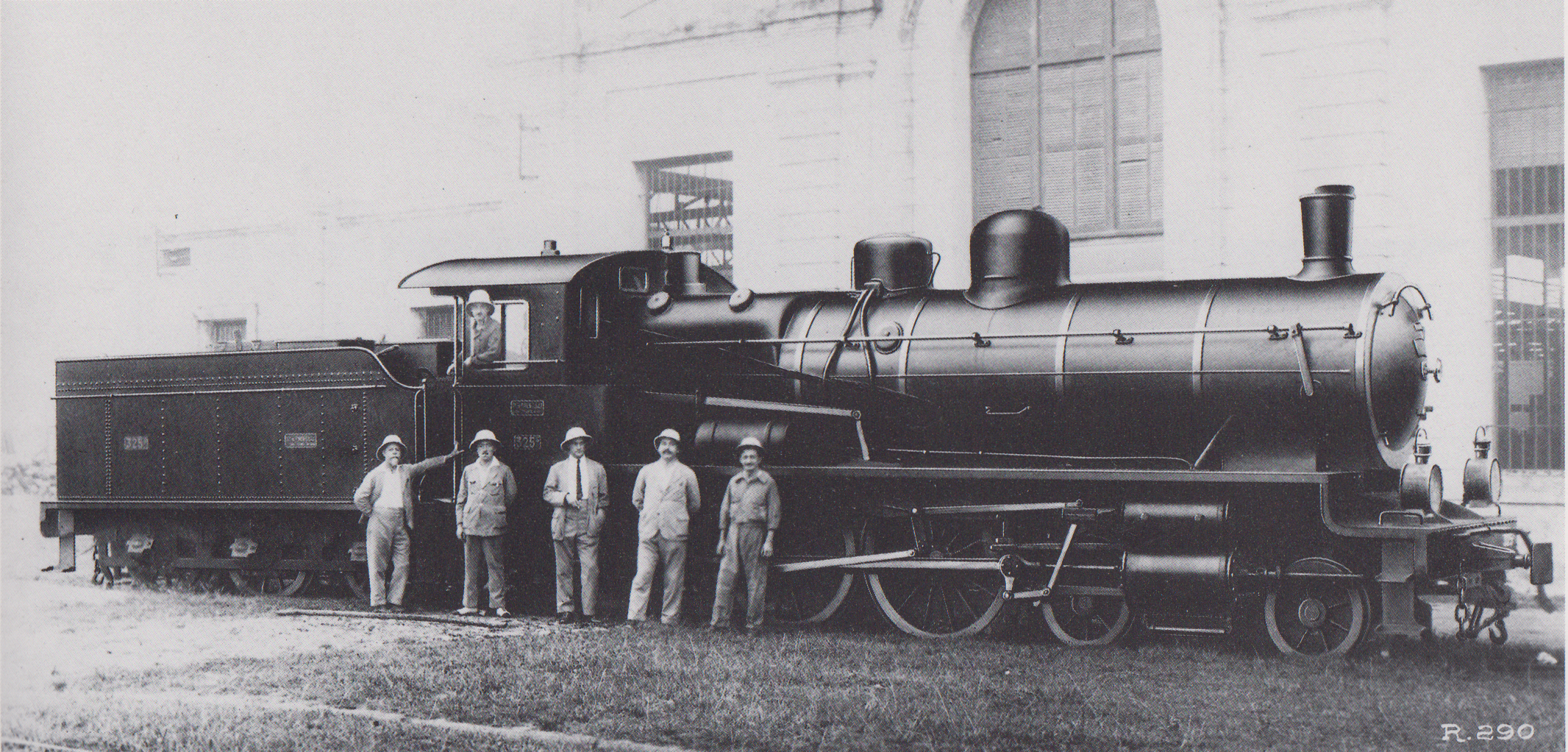

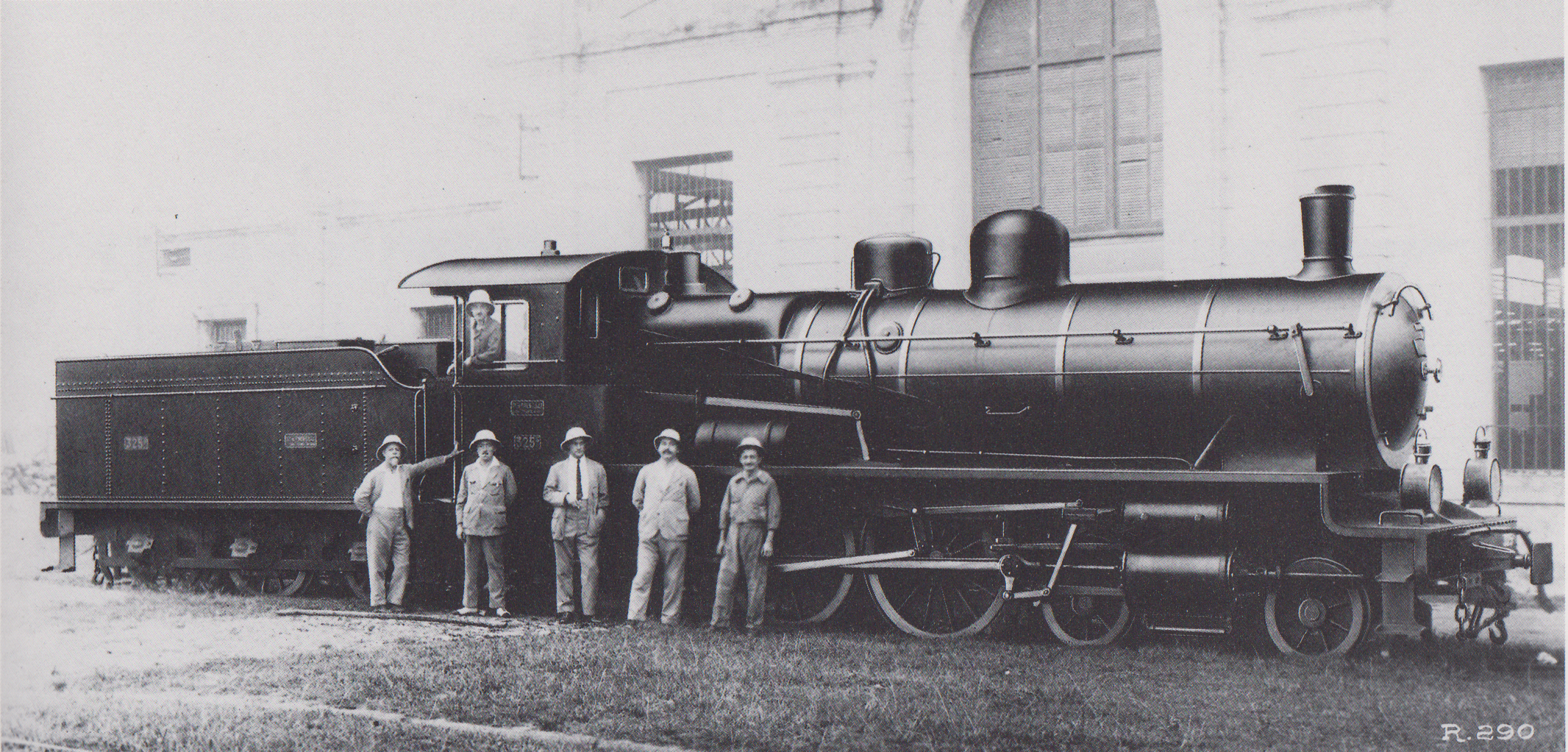

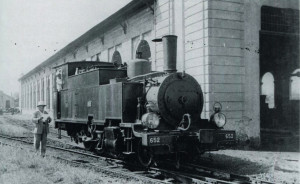

J F Cail 4-6-0 “Ten wheel” locomotive No 235 pictured in the works before delivery to Indochina

Translated from an article in Revue générale des chemins de fer, July 1928

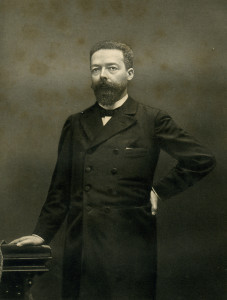

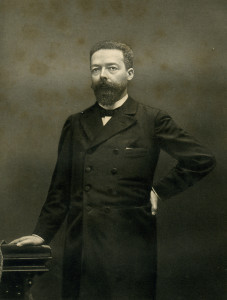

Paul Doumer (1857-1932)

It was in 1897, with the arrival of Paul Doumer as Governor-General of the Colony, that the issue of Indochina Railways began to be studied seriously. At the time of his arrival, only two railway lines had been built, namely, the one running from Saigon to My-Tho and the one running from Phu-Lang-Thuong to Lang-Son, both of which will be discussed later.

Governor-General Doumer developed a comprehensive plan for an Indochina Railways network. He envisaged the creation of “a network to cross the whole of Indochina from Saigon to Tonkin, connecting the ports of the coast with the rich valleys of Annam, connecting the sea with the major navigable reaches of the Mekong, and penetrating China by the Red River Valley.” The planned length of this network reached 3,200km, and according to the available capital, it was thought that we could immediately build between 600 and 1200km of railways, chosen from amongst the lines considered most useful for colonisation.

Notably included in the overall plan were the following railway lines, whose construction, considered especially urgent at the time, was only recently completed, due to the long delays inflicted on all our enterprises by the Great War.

– Haïphong to Hanoï and Lao-Kay at the frontier with China

– Laokay across the frontier to Yun-Nan-Sen in China

– Hanoï to Nam-Dinh and Vinh

– Tourane to Hué and Quang-Tri

– Saïgon to Khanh-Hoa and the Langbian plateau

– My-Tho to Vinh-Long and Can-Tho

Merchant shipping on the arroyo Chinois in Saigon

The potential usefulness of this network was stated clearly in the explanatory memorandum on the aims of the project, which was appended to the law authorising its construction. It stated:

“In Indochina, the forests of Upper Cochinchina, of Cambodia, of Laos and of Upper Laos, the mines of Laos, and the upper valley of the Red River, are all unexploitable due to the absence of transportation. Neither can rice from Cambodia, nor the varied products of Annam, access the rivers or ports from where they could be exported to markets where demand abounds.”

On the other hand, the region of Annam has recently been suffering from famine, and while rice was accumulating in large quantities in neighbouring provinces, it was physically impossible to transport it to the worst affected areas.

We also see that vast new lands have been placed under our sphere of commercial influence, but as yet, French products cannot reach these lands due to lack of roads and inexpensive forms of transportation.

To find out why it is necessary to build an extensive network of railways, you need look no further than the map of Indochina, which shows that while some of its rivers and waterways are suitable for navigation by sail and steam ships, many others are inaccessible to boats of even the smallest tonnage for much of the year.

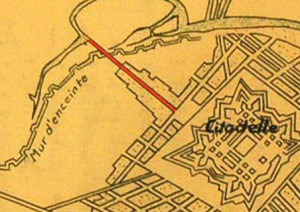

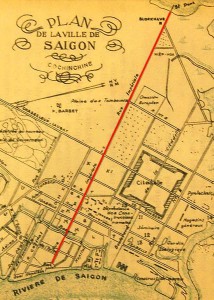

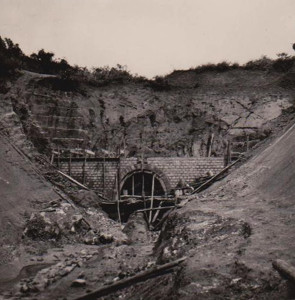

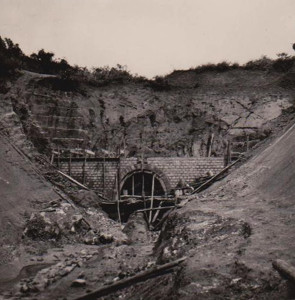

Construction of the Saigon-Mỹ Tho line

To the economic considerations that affect everyone, we must also add the political and military considerations which it is not necessary to dwell upon.

The railway has, moreover, the advantage of opening up to both colonial settlers and Vietnamese people the higher regions, where temperature and soil are favourable and Europeans may find a climate in which they can live and work healthily.

We can now understand more fully how, from the earliest days of our Colony, the creation of railway lines has appeared desirable.

Before 1898, there were, as we said, only two railway lines, those running from Saigon to My-Tho in Cochinchina and from Phu-Lang-Thuong to Lang Son in Tonkin.

The scheme to build the line from Saigon to My-Tho was drawn up in around 1880. Conceded to a concessionaire company in 1881, the line, with a total length of 70km, was put into service in 1885 and initially gave very disappointing results. Then the operation passed to another concessionaire company, the Compagnie des Tramways à Vapeur de Cochinchine. Currently it is the Colony itself which ensures the line’s exploitation.

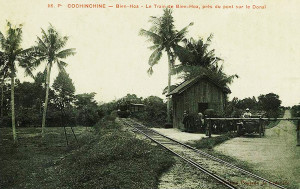

A train leaves Mỹ Tho for Saigon

Running entirely through populated parts of Cochinchina, it connects the two important cities of Saigon and My-Tho via the great city of Cholon, almost entirely populated by Chinese immigrants who hold a monopoly on the export of rice. As a result of this fact, its traffic per kilometre is now much higher than that of all the other lines of Indochina. It cuts through a country of wide rivers, and its route includes several major iron bridges which were built in difficult conditions, given the nature of the soil in this great plain of Cochinchina, formed by the alluvial deposits of the Mekong. The total cost of construction reached 11.6 million francs, corresponding to a cost per kilometre of 165,000 francs.

As for the line from Phu-Lang-Thuong to Lang Son, which eventually became the line from Hanoï to Na-Cham on the Chinese frontier, it was first built in response to military concerns, to ensure easy transportation and supply of French troops taking part in the conquest of Tonkin, pacifying the North and Northeast along the Kouangsi border. Strong garrisons were maintained in these areas and we were thus led, in 1889, to build this line, which was deemed essential.

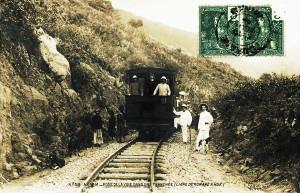

A Decauville 0-4-0 locomotive on the original Phủ Lạng Thương–Lạng Sơn 0.6m gauge railway line in the 1890s

When it was first built, the line did not reach as far as Hanoï, stopping instead at Phu-Lang-Thuong village, which was connected by river with Hanoï and Haïphong. Its primitive 0.60m Decauville rails were replaced in 1896 by 1m gauge track, and at that time it was also decided to extend the line to Hanoï. To this end, in order to cross the Red River near Hanoï, we built the famous Doumer bridge, with a total length of 1,682 metres between abutments, which represented an expense of about 6 million francs. With the completion of this bridge in 1902, the line from Hanoï to Dong-Dang was placed in operation throughout its length. More recently, an additional 17km stretch was built to connect Dong-Dang with Na-Cham on the Chinese border. This line, thus completed, extends over a length of 179km. Its construction cost 45,300,000 francs, approximately 246,000 francs per kilometre.

Let’s return to the 1898 programme, the implementation of which involved the construction of all the lines currently open to exploitation. It provided for the creation of two major arteries:

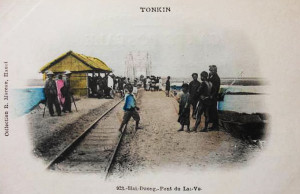

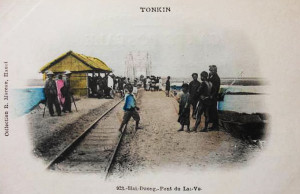

The Lai Vu Bridge, Hải Dương

(i) The Yunnan line – a line of penetration into the large Chinese province of Yunnan, made possible by the Franco-Chinese Convention which was negotiated after our intervention in favour of China at the conclusion of the peace treaty which ended the Sino-Japanese War. Running parallel to the Red River, this line runs from Haïphong to Hanoï, crosses the border at Lao-Kay (384 km) and terminates at Yunnan-fu, its total length being 859km.

(ii) The Transindochinois – a coastal line, bringing together the various territories of the Colony, which will eventually become a great artery running from Hanoï to Hué, Saïgon and Phnom-Penh.

To this effect, the Law of 25 December 1898 authorised the colony to be issued with a loan of 200 million francs, repayable at 3½% over a period of 75 years, not guaranteed by the French state. This 200 million franc loan was to be used as follows:

– Haïphong to Hanoï and Laokay: 383km, 50 million francs

– Hanoï to Vinh: 326km, 32 million francs

– Tourane to Hué and Quang-Tri: 175km, 24 million francs

– Saïgon to Khanh-Hoa and Langbian: 650km, 80 million francs

– My-Tho to Vinh-Long and Can-Tho: 93km, 10 million francs

– Total: 1,627km, 196 million francs

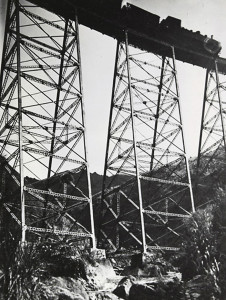

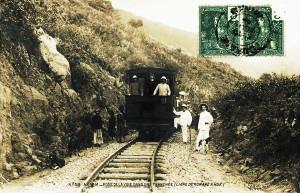

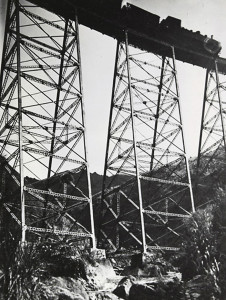

A train passing over the pont en dentelles (“steel lace bridge”) at km 83 on the Chinese stretch of the Yunnan line

Under the terms of the concession agreement to the private company running the Yunnan line, the concessionnaire had to build, at its own expense, the Chinese-section from Lao-Kay to Yunnan-fu (not mentioned above), with the help of the Colony.

It was in 1901 that work began on all of these diverse lines, the expenditure on which is given below:

1. Haïphong to Lao-Kay

Length: 384km

Year commenced: 1901

Year opened to exploitation: 1903-1906

Total construction cost: 78,000,000 francs

Construction cost per kilometre: 203,500 francs

2. Hanoï to Vinh

Length: 326km

Year commenced: 1901

Year opened to exploitation: 1905

Total construction cost: 43,000,000 francs

Construction cost per kilometre: 132,000 francs

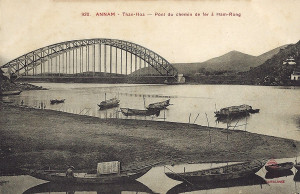

3. Tourane to Hué and Dong-Ha

Length: 175km

Year commenced: 1901

Year opened to exploitation: 1908

Total construction cost: 31,800,000 francs

Construction cost per kilometre: 181,500 francs

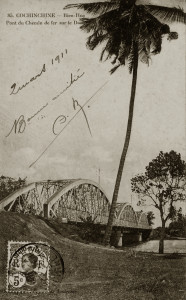

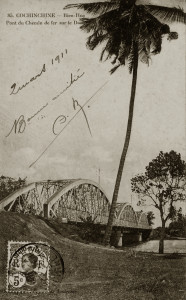

The Bình Lợi Bridge outside Saigon

4. Saigon to Khanh-Hoa and Langbian

Length: 466km

Year commenced: 1901

4.1 Saigon to Tan-Linh (km 132)

Year opened to exploitation: 1908

4.2 Tan-Linh to Khanh-Hoa

Year opened to exploitation: 1913 (except for the Langbian branch, which has only recently been partially executed and opened to exploitation)

Total construction cost: 69,000,000 francs

Construction cost per kilometre: 353,000 francs

As we can see, the construction work was much more expensive on the line from Haïphong to Lao-Kay and Yunnan-fu than on the others. The first section from Haïphong to Lao-Kay crosses the Tonkinese Delta, then travels up the Red River Valley. As for the second part, built in Chinese territory and running from Lao-Kay to Yunnan-fu, its construction met many difficulties, in the recruitment of a poor-quality workforce, in the adverse conditions of both climate and security, and finally in the topography of the area, which required the construction of many important works. It is thus that in the 465km section from Lao-Kay to Yunnan-fu, we had to build 155 tunnels with a total length of 17,864m, and no fewer than 3.422 viaducts, bridges and aqueducts. It is understandable, therefore, that under these conditions, the price of construction could reach a sum so large, the largest for all of our colonial lines and that one could rightly say that this line of Yunnan was the “museum” of the difficulties encountered by engineers in the construction of our railways.

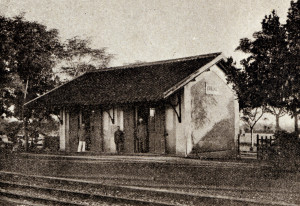

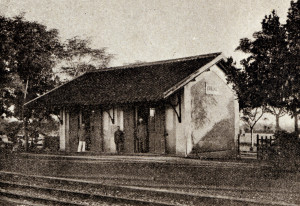

Phủ Lý Station

As for the coastal section of the Transindochinois from Hanoï to Vinh (Annam), this line first ran through the Red River delta before crossing the Tonkin-Annam border at Bim-Son (km 142). It then traversed the deltaic region of Thanh-Hoa, terminating at Vinh (321 km) in the Song-Ca Valley.

The profile of this line is very rugged. An almost entirely rice growing area, the region it passes is populated and prosperous. A 5 km branch line connects Vinh with the port of Ben-Thuy.

The section of the Transindochinois from Tourane to Hué and Dong-Ha is divided into two parts: the first 50km stretch is quite hilly and includes many bridges. The rest of the line travels along the coastal plain, serving another fairly well populated region.

Finally, in the southernmost section of the Transindochinois, from Saigon to Khanh-Hoa and Langbian, the line runs through producing areas between Saigon and Bien-Hoa, then across heavily forested lowland to rejoin the coast of Annam at Muong-Man, a station from where a 12km branch leads to the region’s largest fishing port of Phan-Thiet. From Muong-Man, it follows the coast of Annam as far as Nha-Trang (409 km). It is to this line that the Krongpha-Dalat branch is connected, opening the doors to the Langbian plateau.

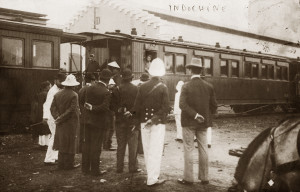

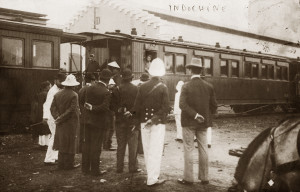

Railway managers supervising construction of the line from Tourane to Huế

These lines, which have been briefly described, are now all in operation. The expenses of building and equipping the lines met by the network are as follows:

Northern Network (Réseau Nord)

Réseaux non-concédés (Non-Conceded Networks)

Total expenses: 88,300,000 francs

Length of lines in operation: 505km

Construction cost per kilometre: 175,000 francs

Annam-Central Network (Réseau Annam-Centre)

Réseaux non-concédés (Non-Conceded Networks)

Total expenses: 31,800,000 francs

Length of lines in operation: 175km

Construction cost per kilometre: 181,500 francs

Southern Network (Réseau Sud)

Réseaux non-concédés (Non-Conceded Networks)

Total expenses: 80,600,000 francs

Length of lines in operation: 536km

Construction cost per kilometre: 150,400 francs

An unidentified CIY Société des batignolles 4-4-0 “Légère” at Hà Nội Station in 1927

Sub Totals, Non-Conceded Networks

Total expenses: 200,700,000 francs

Length of lines in operation: 1,216km

Construction cost per kilometre: 165,000 francs

Compagnie du Yunnan

Réseaux concédés (Conceded Networks)

Total expenses: 243,500,000 francs

Length of lines in operation: 859km

Construction cost per kilometre: 283,500 francs

Totals, Non-Conceded and Conceded Networks

Total expenses: 444,200,000 francs

Length of lines in operation: 2,075km

Construction cost per kilometre: 214,000 francs

We see that the total expenditure far exceeded the 200 million franc loan of 1898, and furthermore that it only provided for an incomplete programme of railway building. Only the construction of the line from Haïphong to Lao-Kay and Yunnan-fu was completed in accordance with the 1898 plan, which provided for a link between the important Chinese province of Yunnan and the international port of Haïphong.

J F Cail 4-6-0 “Ten wheel” locomotive No 316 at Tuy Hòa (CAOM)

Moreover, apart from in Tonkin, our interior rail communications are not yet well assured and the meeting of various territories has only just been begun with the building of three separate sections (North, Annam Central, South) of the Transindochinois.

New loans were thus sought with the purpose of completing the first stage of the 1898 programme and studying and building new lines. But because of the outbreak of the Great War, these enterprises unfortunately experienced significant delay. It’s thus, for example, that the line connecting the Northern and Annam-Central Networks from Vinh to Dong-Ha, begun in 1913, has only recently been opened to exploitation; its length is 299km. The same may be said for the Krongpha-Dalat (Langbian) branch on the Southern Network, which was incorporated in the 1898 programme but is still only partially open to exploitation. Its 84km route incorporates steep gradients of 12% and it is equipped with rack and pinion equipment on some sections.

Having thus reviewed the lines of the partially-completed 1898 programme, the exploited length of which currently reaches nearly 2,400km, let’s now say something about the lines which are projected or under study, in accordance with the overall programme to develop our colonies introduced in 1921 by M. Albert Sarraut.

Việt Trì station

In fact, it is now more necessary than ever to develop our railway network. However, construction of new railway lines should now be less of a challenge than it was originally, from the point of view of financing and construction as well as with regard to the expected results of operations. It is no exaggeration to say that the lines currently under consideration will influence the development of the Colony much faster than the first lines which were built, because much of the 1898 Doumer programme was in fact a foundation which must now be completed in order to produce its full effect.

The new lines which the 1921 programme envisaged as essential to the development of the colony are:

1. The Tan-Ap to Thakhek line, 186km

2. The Tourane to Nha-Trang line, 550km

3. The Saigon to Phnom-Penh and Siam line, 632km

4. The My-Tho to Vinh-Long, Can-Tho and Bac-Lieu line, 285km

These comprise a total of 1,653km of railway. which, in addition to the approximately 2,400km already in operation, will bring the total length of our Indochina rail network about 4,000km.

Société Franco-Belge 4-4-0 “Américaine” locomotive No 220 arriving at Vinh station (CAOM)

The first of these lines, from Tan-Ap to Thakhek, will link the Vinh to Dong-Ha section of the Transindochinois at Tan-Ap station with the navigable reaches of the Mekong in Thakhek, on the Lao-Siamese border; its route will cover 53km in Annam and 133km in Laos, with gradients of 15mm on the Annamite side and 8mm on the Lao side. As it is expected that freight carried on the line will mostly be export traffic, heavy trains will only have to climb the lowest gradients on the Lao side. The cost of building this line has been estimated at 15 million piastres (in 1927 the average exchange rate for the piastre fluctuated at around 12.75 francs), giving a cost per kilometre of 80,000 piastres.

The Nha-Trang to Tourane line, construction of which will mark the completion of the Transindochinois, responds to a pressing need. Urgently requested by the elected body of Cochinchina, it should indeed permit important exchanges between Tonkin and Cochinchina (eg the movement of agricultural labour to the south) as well as the transportation of crops from the irrigated plains of Central and South Annam to the north. This section of the line, with its total length of 550km, will cost 38 million piastres, or 70,000 piastres per km. Definitive studies and operations on site have been ongoing since 1923.

Weidnecht 130-T locomotive No 652 at Hà Nội Depot (CAOM)

The line from Saigon to Phnom Penh and the border of Siam, which should serve the north of Cochinchina and reach the Siamese border through the western part of Cambodia, also meets an urgent need. It crosses fertile areas which are already under cultivation, but, for lack of transportation, cannot be properly developed. On the other hand, the existence of the neighbouring Siamese rail network threatens to divert all traffic from one part of Cambodia (Battambang region). Our new line will link the Indochinese and Siamese networks, facilitating trade and movement of travellers between Bangkok and Saigon, which can only grow in future. Implementation of this 632km line should cost around 45 million piastres, or 71,200 piastres per km.

The construction of the last new line, from My-Tho to Vinh-Long, Can-Tho and Bac-Lieu, will be be less urgent than the previous ones, although it was planned long ago. It corresponds to an expense of 20 million piastres of expenditure for 285km, or 96,000 piastres per kilometre. This high figure is due to the large metal structures which will need to be built in order to cross the Mekong, Cochien and Bassac.

Constructing the final Tourane-Nha Trang stretch of the Transindochinois

One wonders whether this large expenditure will be sufficiently remunerated by a traffic that we do not expect to be very important, dependent as it will be upon merchants whose goods already flow easily on the canals which criss-cross the country, and travellers who increasingly use automobiles or public buses.

The four railway lines which we have described will thus have an overall cost of 118 million piastres. A sum of 100,000,000 piastres has already been assigned to them as part of the programme developed in 1924 by the Government General, which spreads over 10-15 years a set of major works deemed necessary to develop the colony.

After this summary of current routes operated and those whose construction is planned, we should say something about the other railway lines under consideration. For once the four lines of the 1921 programme are complete, it is highly likely that other lines will be commissioned, enhancing the value of our Far East possessions.

Constructing the final Tourane-Nha Trang stretch of the Transindochinois

For example, one may also envisage, in Annam, the construction of a branch line leading off the Transindochinois in the region of Tuy-Hoa (on the section from Tourane to Nha-Trang) and travelling across the Djaraï plateau to Pleiku. Perhaps the colonisation of this ethnic minority region may also require a line from Saigon heading up to Bandon via Loc-Ninh and Bu-Dop, with an additional branch from Loc-Ninh to Kratie. Equally, we may be able to realise a railway line from Phnom Penh to Kampong Thom, which crosses northern Cambodia and the province of Bassac, extending as far as Pakse and Savannakhet, and connecting two lines already in the planning stages, namely those from Saigon to Phnom Penh and Siam and from Tan-Ap to Thakhek. It’s easy to see the great advantages which could accrue to the Colony from such an increase in its means of transportation, in parallel with the development of all other means of production.

Technical considerations – The Indochina railway network is equipped with 1m gauge track; the trackbed width is 4.40m, in anticipation of a rolling stock body width of 2.80m.

A station scene in the late 1920s

The maximum curve radius is 100m and the maximum gradient is 15mm, except on some parts of the Langbian line, which are equipped with rack and pinion equipment. In Chinese territory, the gradients of the Yunnan line reach 25mm.

Smaller structures are built with ordinary masonry. Major works incorporate metal decking. Concrete has been widely used on recent lines. Bridges are built for both road and rail traffic.

The rail itself weighs, according to the lines, 20, 25 or 27kg per metre. On those lines which remain to be built, the rail weight is 30kg and gradually the other lines will be equipped with this sturdier rail. The metal sleepers now employed on the Yunnan and many other networks give the best results. The weight of a sleeper with its accessories is 40kg and one kilometre of line is equipped with 250 sleepers. Wooden sleepers, used first in forested areas, tend gradually to be abandoned.

Văn Xá Station, north of Huế.

Smaller stations are of simple design and comprise only one building for freight and passenger usage. The most important stations are more like those of the métropole. The issue of signage, of little concern until recently, is currently being studied further, because of ever-increasing traffic.

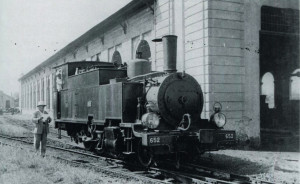

Locomotives used most widely are those with six coupled driving wheels and an adhesive weight of 30 tonnes. They can haul loads of 300 tonnes at 40kmh and 370 tonnes at 20/25kmh.

On the Yunnan network which, as we have said, has long gradients of 25mm, more powerful locomotives with eight coupled driving wheels and an adhesive weight of 40 tonnes are used. The Langbian (Krongpha-Dalat) line uses mixed adhesion and cog rail systems.

Finally, locomotive boilers are heated by coal in Tonkin and Yunnan, where this fuel is abundant, while in the heavily forested Annam-Central and Southern Networks, a more economical heating solution is found by using wood.

Chemin de fer de l’Indochine. Intérieur d’un wagon de 4ème classe

Travellers have a choice of four classes. Most often, the first three classes are grouped in mixed carriages with corridors. The fourth class is almost exclusively used by local people, who provide over ⅘ of total passenger revenue.

Unlike others, the carriages of this class do not include compartments, but are fitted with longitudinal benches fixed against the side walls, leaving the central portion free for luggage.

The weight of the passenger carriages, all of which have two bogies, is about 16 tonnes.

Freight rolling stock is of the current type for 1m gauge railways.

In the technical field, steady growth in traffic has led to consideration and implementation of many improvements, specifically, increasing the quantity of locomotives and rolling stock, replacing old vacuum brakes with automatic brakes, installing modern signalling systems, strengthening existing track, and providing more appropriate equipment for stations. The programme established for this purpose will be fully realised quite soon, for a price we have estimated at about 5 million piastres.

La montee du Col des Nuages (Annam)

Consideration of commercial exploitation – where the operation of the railway is concerned, we must first of all consider separately the railways of the Colony (the Réseaux non-concédés or Non-Conceded Networks) and the railways franchised to concessionnaires (the Réseaux concédés or Conceded Networks), of which the Yunnan line is the only current example.

The former are grouped into a “circonscriptions” of operation, each under the authority of a Chief Engineer who reports directly to the Inspector General of Public Works of Indochina. Each circonscription has its own budget, fed by operating revenue. It also has special funds outside the budget, working capital (supply of materials and funds), a special fund for additional works and supplies, and reserve funds to cover insufficiency in deficit years.

The internal organisation of the private company which has been granted the franchise to run the Yunnan line offers no unusual features. The financial regime for exploitation provides for the reimbursement of all actual expenses incurred in the maintenance and operation of the line; it also provides a special fund for additional works of exceptional importance.

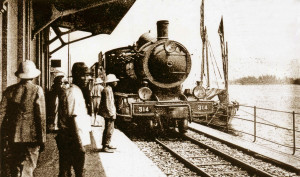

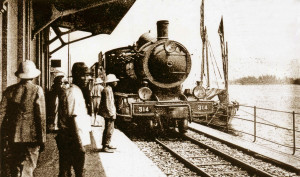

J F Cail 4-6-0 “Ten wheel” locomotive No 314 entering Tourane Marché station

Surplus operating revenues are first used in the service of committed capital and to cover central administrative costs. Any left-over surplus is then shared, under certain conditions, between the Colony and the company. Talks were recently scheduled to establish a new operating system for conceded networks.

Overall, the railway is staffed by Europeans in senior executive positions and Vietnamese at officer-level and below (station managers, train and machine operators, workshop employees and track maintenance staff). The Yunnan Company employs a higher proportion of European staff than the Colony.

The main features of railway operation are:

Passenger traffic was relatively high following the opening of the first lines, and showed a steady increase from 1908 to 1920. However, since 1921, it has manifested a downward trend, due to very active competition from motor transportation, which has been increasingly developed in recent years. In fact, between 1920 and 1925, rail passenger traffic suffered a reduction amounting to around 30%.

A northbound train heads through Biên Hòa

The current success of the automobile is explained because at present the Vietnamese traveller undertakes only short trips; long journeys have not yet become part of his habits. This situation will certainly change with the completion of Transindochinois, creating very large currents of long-distance traffic which the railway alone can service. Against this trend, we have also successfully developed measures to persuade local people to use the railway more – specifically through reduced ticket prices, which have significantly increased revenue.

As for freight traffic, it is constantly increasing. For both networks (Colony and Yunnan), in 1924 this traffic represented more than 140% of that in the pre-war period. The number of kilometric tonnes, which stood at 86 million in 1920, increased to 123.3 million in 1924, increasing by approximately 44%. The continuous growth in freight traffic has been so rapid that the rolling stock, which could meet all needs back in 1920, is now clearly insufficient. This failure has cost the railway part of the traffic it could normally service, and to remedy this, we have had to order large numbers of new wagons and locomotives.

Deraillement causé par un éléphant

Regarding ticket prices, it appears that, overall, the prices of the Colony’s railways are rather low. This, perhaps, to some extent explains why the lines of Indochina see much more intense traffic than other colonial networks. Indeed, before 1914, when the piastre exchange rate was on average 2.50 francs, the number of passengers per kilometre on the Indochinese lines was reported to be half of that reported on other French colonial lines, and the tonnes per kilometre of freight transported in Indochina amounted to just a quarter of that transported on our African lines.

Currently, because of the high value of the piastre, the comparison would be less conclusive.

However the fact remains that the Indochinese rail ticket prices are much lower, when compared to those of railways elsewhere in the Far East, operated in similar conditions.

If we make a comparison with Siam, a country similar in all respects to our colony, we find that the average freight revenue per tonne on Siamese lines is twice that on our Indochinese lines, while a traveller, who yields to Siam two hundredths of a piastre per kilometre, yields less than one hundredth of a piaster per kilometre here in Indochina.

Thanh Hóa Bridge

This is why, despite their superiority in traffic intensity, the railways of our Colony show a certain inferiority when it comes to their receipts.

The receipts per kilometre in recent years amounted to, on average, between 3,560 piastres per annum for all lines (4,800 piastres for Yunnan, 2,750 piastres for the colonial network).

The corresponding expenditure per kilometre amounted to 2,850 piastres (3,500 piastres for Yunnan, 2,400 piastres for the colonial network).

The average operating ratio stood at 74% on the Yunnan network, 87% on the Colonial network, and 80% overall. In order to explain the lower operating ratio of the conceded company, it must be explained that its tariffs are higher in general than those on the Colony’s network.

The overall situation of our Indochina railways is quite satisfactory and in future it cannot, it seems, but improve. No doubt currently the net profit is not enough to compensate, as appropriate, the capital outlay; but it is expected to do so soon, as long as traffic continues to follow the progress of recent years.

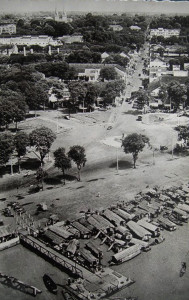

Saigon Station in 1929

We should not, however, measure the value and success of the railway solely according to the financial results. It should be considered that the railway, even more than the road, is a tool for the exploitation and development of the colony, and not a stand-alone fiscal instrument. The characteristics that we have been able to demonstrate – that the relatively weak financial performance of the Indochinese rail network does not derive from the country’s poverty, nor from the lack of traffic, nor from over-expensive operation, but only from the extremely low level of prices – constitute a very reassuring finding. Thus it is that the receipts the railway has failed to generate may be found, stronger, in many other areas, the product of increased economic activity which has only been made possible thanks to inexpensive rail transportation. This is why a general increase in ticket prices, always a delicate operation considering its potential impact on traffic, has been considered with extreme caution in Indochina, especially if one takes into account the extent of competition from waterway and automobile.

Hà Nội Station booking hall in 1927

As currently managed, the Indochina railway is an instrument for the development and prosperity of the country through which it passes, since it is only by the mere increase in traffic that it can improve its financial performance. This traffic, which has increased significantly since 1920, will soon be able to grow even more, thanks to the availability of new wagons and locomotives. But it will not achieve its full potential until the Indochina rail network has been fully realised in line with the programmes of 1898 and 1921.

Tim Doling is the author of The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, Bangkok, 2012) and also gives talks on Việt Nam railway history to visiting groups.

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group Rail Thing – Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam for more information about Việt Nam’s railway and tramway history and all the latest news from Vietnam Railways.

You may also be interested in these articles on the railways and tramways of Việt Nam, Cambodia and Laos:

A Relic of the Steam Railway Age in Da Nang

By Tram to Hoi An

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Vietnam Railways Building

Derailing Saigon’s 1966 Monorail Dream

Dong Nai Forestry Tramway

Full Steam Ahead on Cambodia’s Toll Royal Railway

Goodbye to Steam at Thai Nguyen Steel Works

Ha Noi Tramway Network

How Vietnam’s Railways Looked in 1927

“It Seems that One Network is being Stripped to Re-equip Another” – The Controversial CFI Locomotive Exchange of 1935-1936

Phu Ninh Giang-Cam Giang Tramway

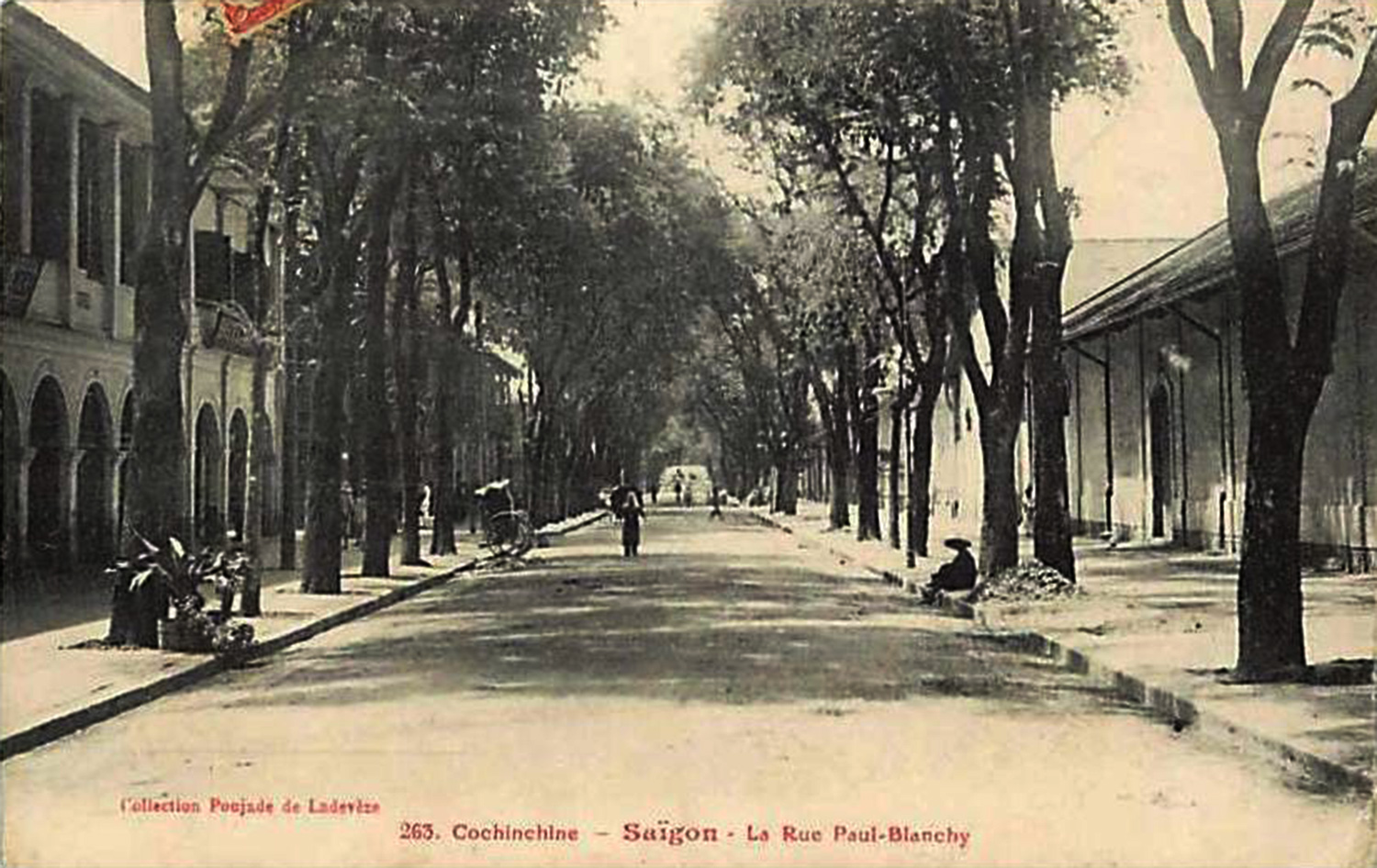

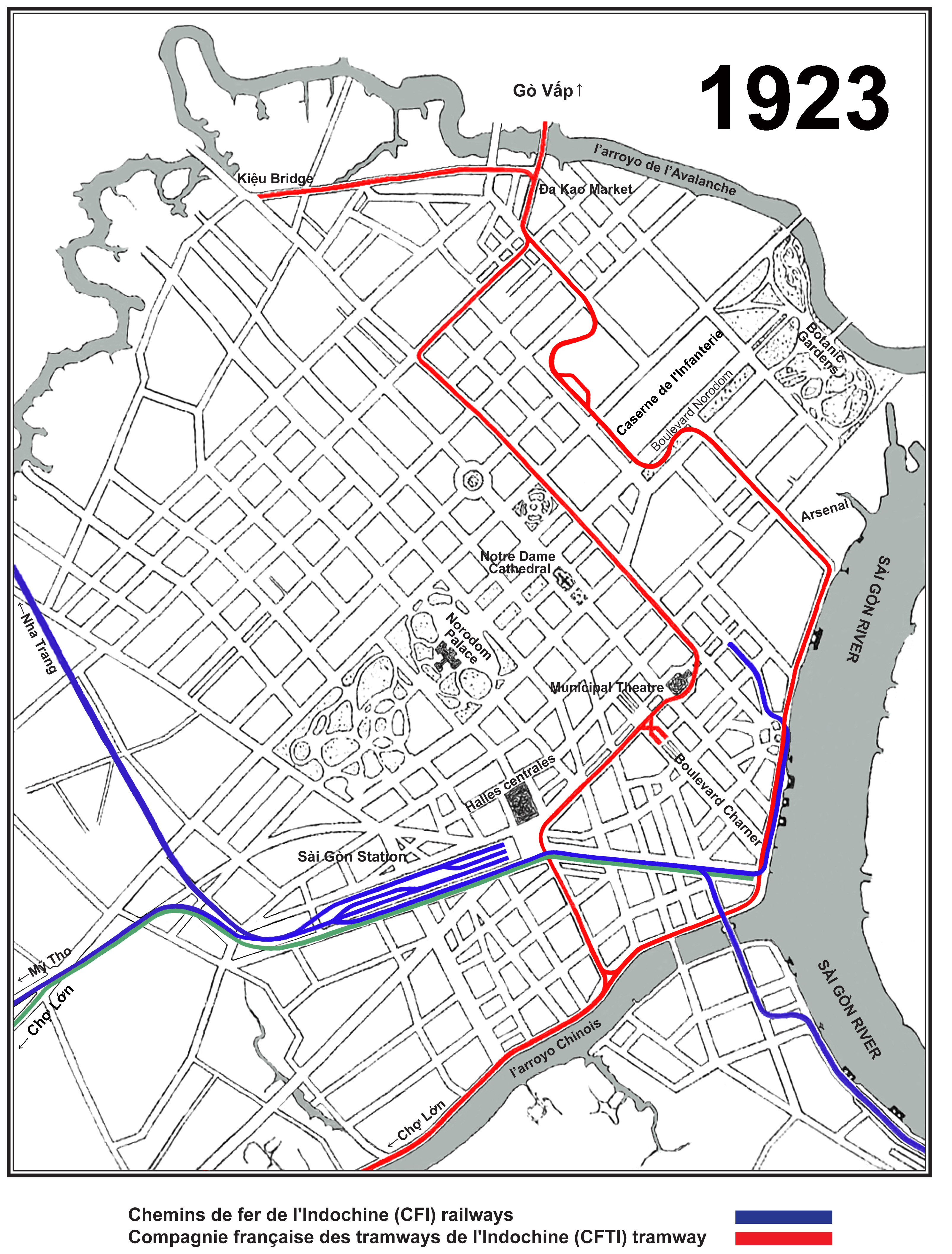

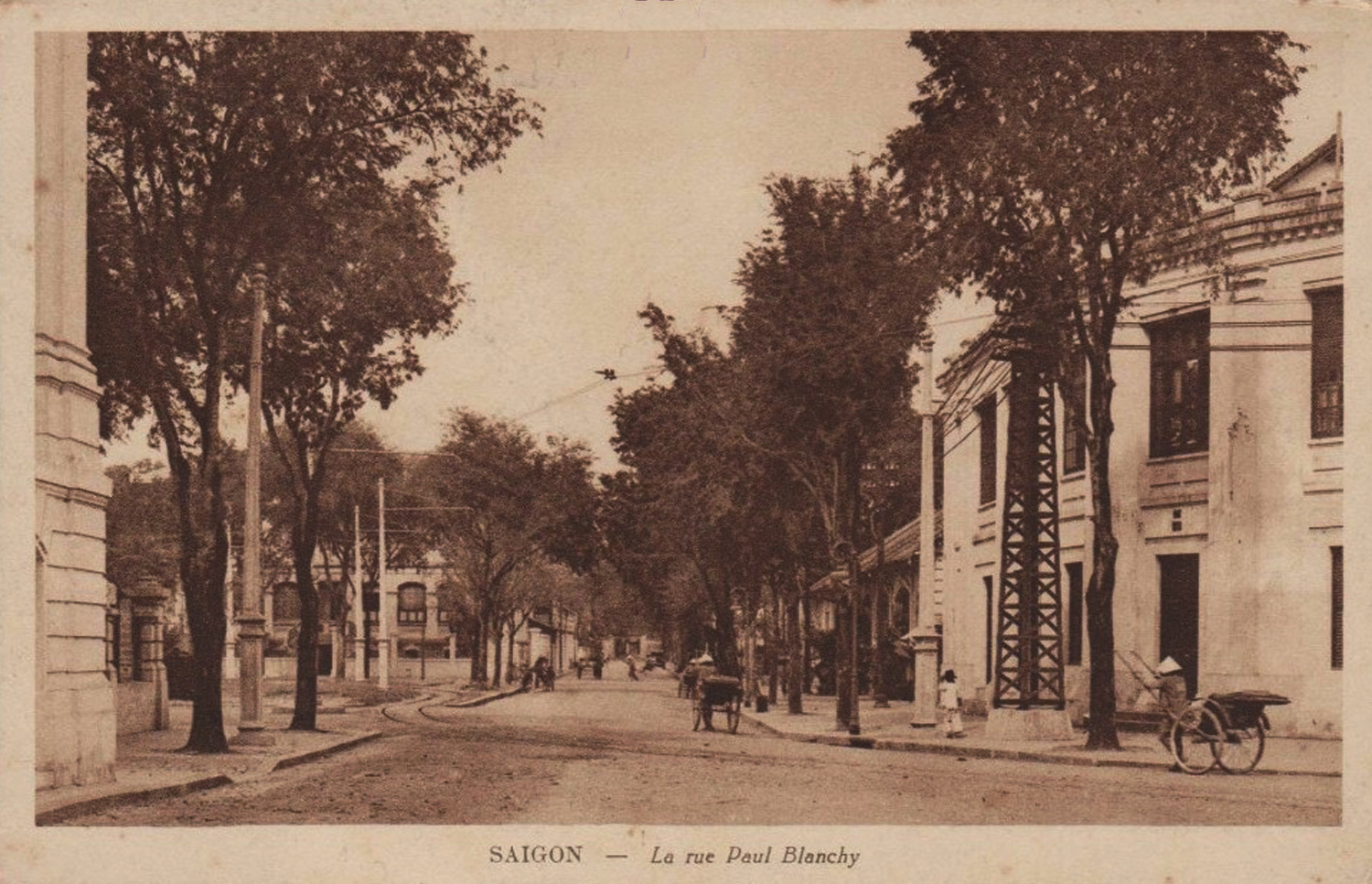

Saigon Tramway Network

Saigon’s Rubber Line

The Changing Faces of Sai Gon Railway Station, 1885-1983

The Langbian Cog Railway

The Long Bien Bridge – “A Misshapen but Essential Component of Ha Noi’s Heritage”

The Lost Railway Works of Truong Thi

The Mysterious Khon Island Portage Railway

The Railway which Became an Aerial Tramway

The Saigon-My Tho Railway Line