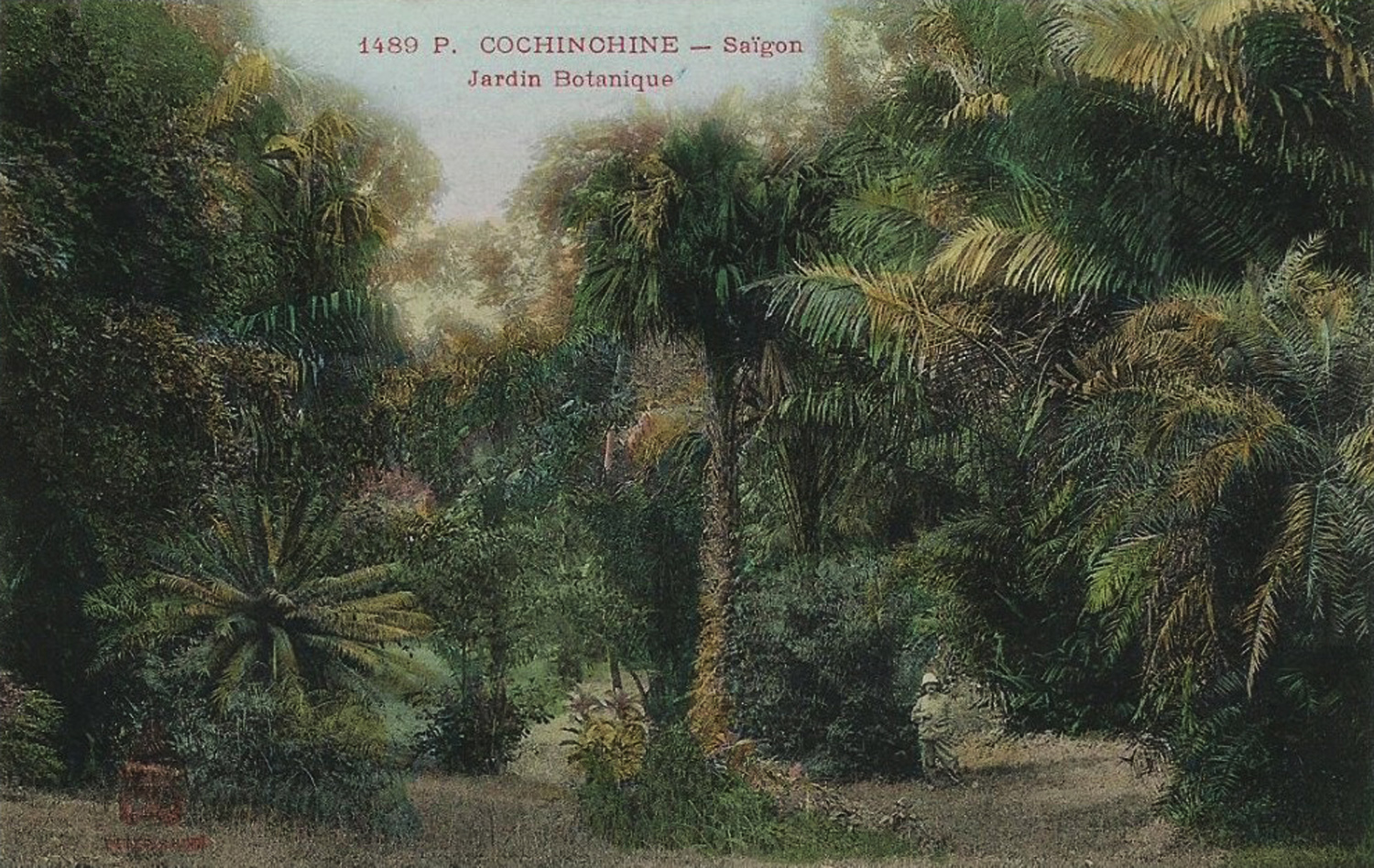

Saigon – the Botanical Gardens

Published on 3 June 1885 to coincide with the Antwerp World Fair (2 May-2 November 1885), Notices coloniales, publiées à l’occasion de l’Exposition universelle d’Anvers en 1885 contains the following description of Saigon, Chợ Lớn and other principal centres of population in French Cochinchina.

1. Saïgon

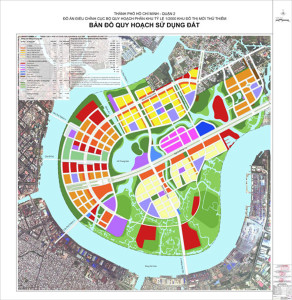

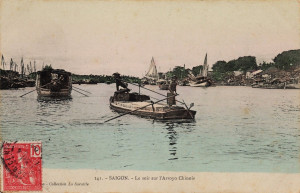

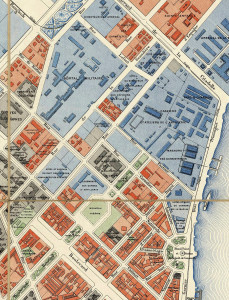

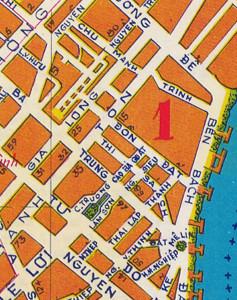

The city of Saigon is enclosed by an irregular trapezoid formed by the Saigon river to the east, the arroyo Chinois [Bến Nghé creek] to the south, the arroyo de l’Avalanche [Thị Nghè creek] to the north and the belt canal (canal de Ceinture) to the west.

The Grand Canal (now Nguyễn Huệ boulevard), pictured in 1882

Our conquest destroyed the old Saigon. The ambitious plan for the new city was more than just a resurrection; to realise this new creation, it was necessary to reduce the size of the plateau which dominated the settlement and to fill marshes which surrounded it, laying streets and building houses on shaky ground. This great work took several years.

The first street we created was the rue Catinat [Đồng Khởi], which was established on the path of an ancient Annamite street leading from the river to the citadel; all other major arteries run parallel to it. To the left of this street is the Grand Canal [Nguyễn Huệ], which permits boats loaded with freight to dock right in front of the main City Market. That market consists of eight large covered halls whose appearance would not look out of place in a large European city; here also, either side of the canal, are the quay Charner and the quay Rigault de Genouilly, which both extend as far as the rue d’Espagne [Lê Thánh Tôn]; and at the top of the canal we planted a lovely square on which a granite monument was erected to the memory of commandant de la Grée, leader of the Mekong expedition.

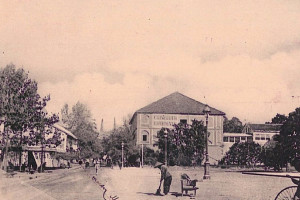

The City Market pictured in the 1880s before the filling of the Grand Canal

To the right of the rue Catinat is the rue Nationale [Hai Bà Trưng], a pleasant thoroughfare 20m in width, which departs from the Rond-point [Mê Linh square] and runs through the entire length of the city. A square has been built on the Rond-point, where five streets converge.

The boulevard de l’Hôpital [Thái Văn Lung] and the boulevard de la Citadelle [Tôn Đức Thắng] also lead from the quayside, running parallel to the rue Catinat. The boulevard de l’Hôpital stops at the rue d’Espagne, while the boulevard de la Citadelle continues as far as the arroyo de l’Avalanche, whence another avenue leads to Binh-Hoa [later Gia Định], seat of the Inspection of Saigon.

All of these roads run from southeast to northwest. They are intersected perpendicularly by many streets, whose direction is southwest-northeast.

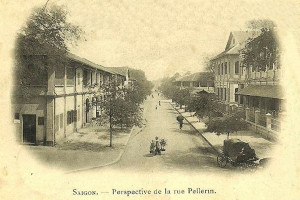

The rue Pellerin (now Pasteur street), pictured in the late 19th century

The most important of these are, starting from the quayside: rue Vannier [Ngô Đức Kế], rue de l’Église [Tôn Thất Thiệp], boulevard Bonard [Lê Lợi], a thoroughfare 50m wide, rue d’Espagne, rue de La Grandière [Lý Tự Trọng], the starting point of the “High Road” to Cholon, rue Tabert [Nguyễn Du], boulevard Norodom [Lê Duẩn], in front of the Palace of the Government, and finally the rue Chasseloup-Laubat [Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai].

Wide streets also lead north from the arroyo Chinois to the Plain of Tombs (plaine des Tombeaux). These are rue Ollivier [Pasteur], rue Pellerin [Pasteur], rue Mac-Mahon [Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa], which at its extremity runs in front of the Palace of the Government, and rue Boresse [Yersin]. In one section of the latter street, which borders the arroyo Chinois, we recently built a petrol store which holds the colony’s entire supply of petrol for two years; behind this store is the city abbatoir.

Saigon – the new quays and docks

All these streets are lined with beautiful sidewalks which cover the vast masonry sewers and have been shaded by the planting of various trees of remarkable vigour, such as tamarind, mango, sao, banana and teak.

The ships of the Messageries maritimes are moored at the entrance of the city, opposite the agent’s headquarters and other important buildings constructed by that company, with the aim of making Saigon the Southeast Asian shipping hub for China and Japan. A beautiful bridge over the arroyo Chinois [Eiffel’s pont des Messageries maritimes or cầu Mống] connects the Messageries to the city, in line with the rue Pellerin.

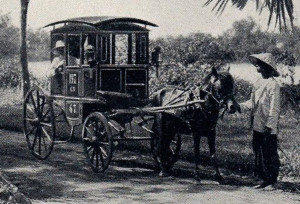

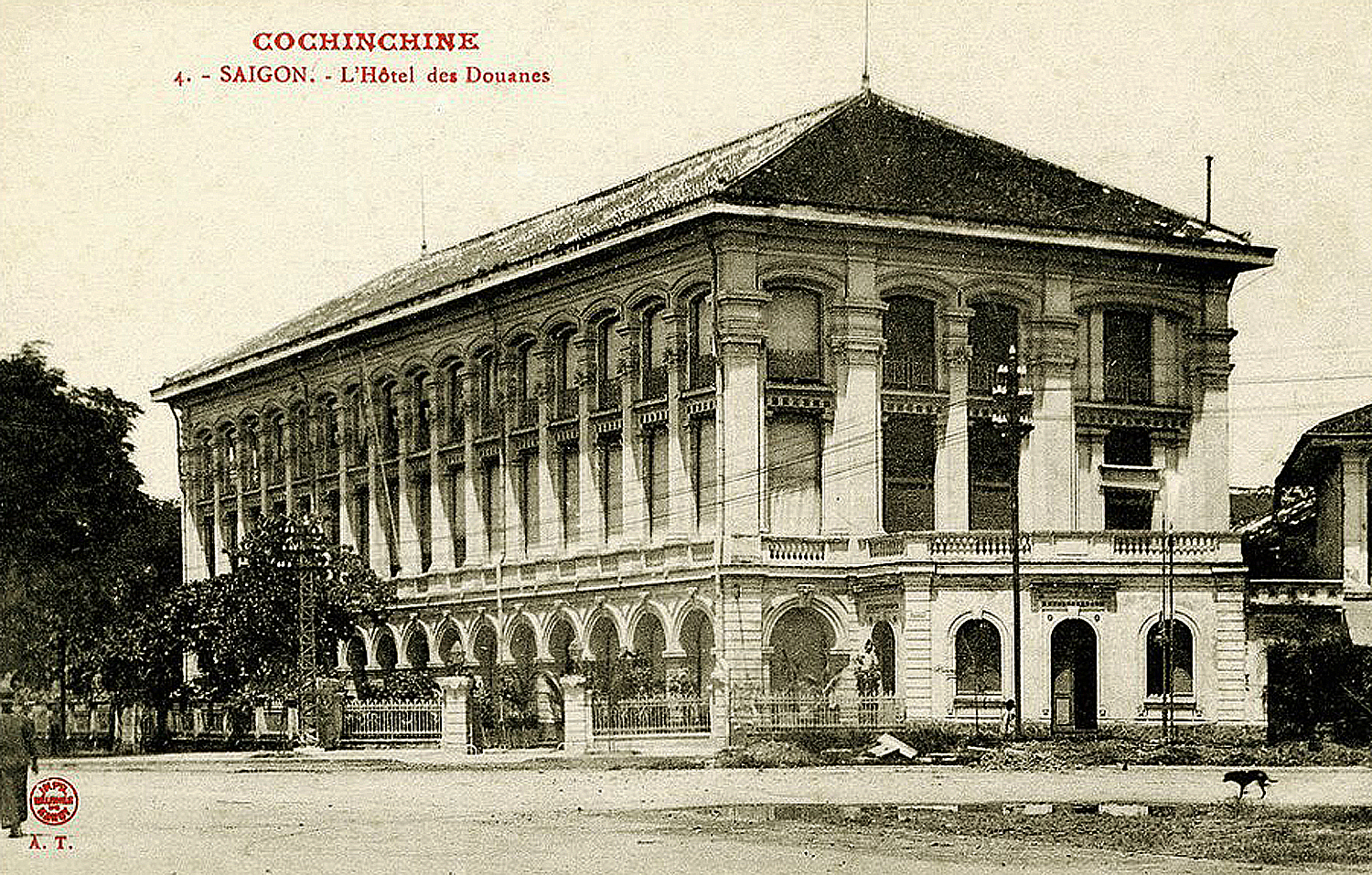

In front of the Messageries, at the junction of the Saigon river and the arroyo Chinois, are the Signal Mast and the terminus for the steam tramway which runs between Saigon and Cholon. From here, walking north along the quayside, one passes the offices of the Commercial Port Directorate and the Maison Wang-Tai, a massive construction raised by a wealthy Chinese, which now belongs to the Customs and Excise administration.

The main entrance to the Naval Artillery, pictured in the late 19th century

Beyond the entrance to the Grand Canal are many cafés, the headquarters of the Compagnie des Messageries de Cochinchine, the Port of War Directorate, and the shipyards and other facilities of the Marine Artillery. Then on the right, one passes the Naval Wharf and the Admiral’s flagship, the Tilsit, the Indochina station Manning Pool [naval barracks], and finally the Arsenal, which interrupts the flow of quays and continues as far north as the entrance to the arroyo de l’Avalanche.

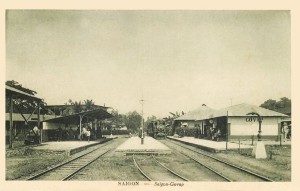

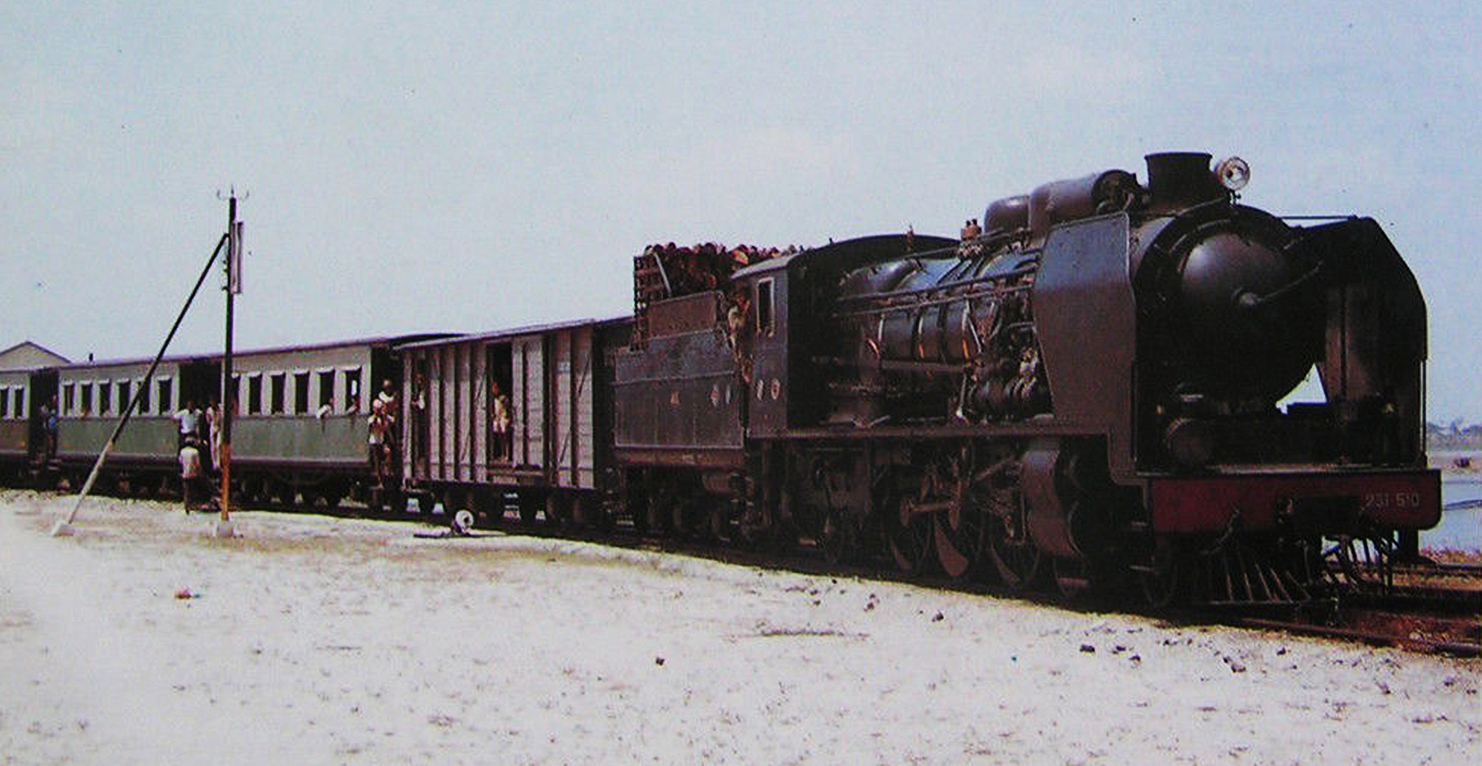

Between the Signal Mast and the commercial port is the Saigon Railway Station, installed by the company which will soon launch a new rail service between Saigon and My-Tho.

The Saigon Arsenal occupies an area of 22 hectares and measures no less than 950m at its greatest length. This is an establishment of the premier order, which employs more than 600 Chinese and Annamite workers.

The Sainte-Enfance (Holy Childhood) complex, run by the Sisters of Saint-Paul de Chartres, pictured in 1866

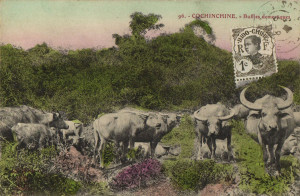

Behind the Arsenal are the Botanical Gardens, which house the pavilion of the director, an aviary containing specimens of all the birds of Cochinchina, enclosures housing herds of deer and buffalo, and ponds where many water birds frolic.

In front of the Botanical Gardens, on the rue de Tay-Ninh [Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm], is the collège d’Adran. Behind it, with their entrances on the boulevard de la Citadelle, are the Seminary of the Mission, the elaborate façade of which catches the eye, and the Sainte-Enfance [Holy Childhood], a vast and beautiful establishment run by the Sisters of Saint-Paul de Chartres. This is a building of mixed design, ornamented in indigenous style and flanked by a Gothic chapel, whose slender and graceful spire dominates the landscape and may be seen from afar. Opposite the Sainte-Enfance, on the boulevard de la Citadelle, is a convent of European and indigenous Carmelite nuns.

The Citadel is a large earthwork with bastions at each corner, measuring 870m on each side and now intersected by the modern rue Chasseloup-Laubat and boulevard de la Citadelle.

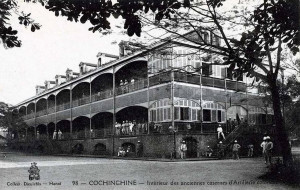

One of the Colonial Infantry Barracks buildings

At the time of our taking Saigon, the Citadel contained huge stores full of rice, which the necessities of war forced us to burn. Within the enclosure, our military engineering corps constructed two magnificent barracks buildings, built of iron and brick and each housing 800 men. These premises, destined for troops of the Naval Infantry, leave nothing to be desired in terms of hygiene and amenities.

The Military [later Grall] Hospital, built to the same architectural design as that of the barracks, with its main entrance on the rue de La Grandière, is a huge facility which consists of a series of large pavilions supported by cast iron frames, connected by covered corridors.

If, on leaving the Citadel, one travels from northeast to southwest, following the rue Chasseloup-Laubat, one passes on the left the old camp des Lettrés [Camp of the literati or Trường Thi, where royal mandarin examinations were once held], which has long served as barracks, and on the right, the Water Tower (Château d’eau) and supply basins. A little further along is the collège Chasseloup-Laubat or École normale supérieure indigene [Lê Quý Đôn High School], a vast building housing 300 students.

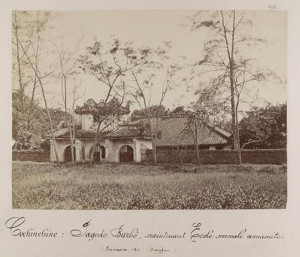

The Barbé Pagoda

Just behind it is the Barbé Pagoda [on the site now occupied by the War Remnants’ Museum], named after the captain who was killed there in an Annamite ambush. It was here that Minh Mang, son of Gia Long, was born; and it was Minh-Mang who originally built this pagoda in memory of his birth.

The Park of the Palace of the Government [later the Norodom Palace] and the City Park [Tao Đàn Park], located next to each other, border rue Chasseloup-Laubat opposite the collège Chasseloup-Laubat.

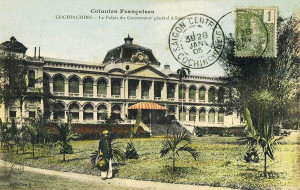

The front façade of the Palace of the Government measures no less than 80m in length. It consists of two pavilions at both ends and a central portion with a dome and covered access ramp. The ground floor, raised over a basement where the kitchens and other service departments are located, contains: on the right, the offices, including the Office of the Governor; on the left, the council meeting room; and in the middle, the dining room, telegraph office and privy council secretariat. Also in the middle is a magnificent vestibule, from which a double width marble staircase leads up to the first floor apartments. Beyond the vestibule is the beautiful and richly decorated events hall (salle des fêtes), which lies perpendicular to the rear façade of the palace and is easily capable of accommodating 800 guests.

The Palace of the Government, soon after its completion in 1872

Leaving the Palace of the Government by the boulevard Norodom, which extends in line with the central axis of the palace, one finds the Bishop’s Palace [on the site now occupied by the Department of Foreign Affairs], the Cathedral and the Cercle des officiers [now occupied by the District 1 People’s Committee], which serves as mess for the marine infantry. The latter is a vast and beautiful property which was established thanks to the solicitude of Admiral-Governor Duperré.

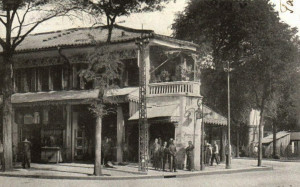

The Cathedral forms the centre of a huge square, in line with the axis of the rue Catinat. The upper part of the rue Catinat, the busiest street in Saigon, along with neighbouring parts of the streets it crosses, are home to all of the main government services. It is at the top end of this street that one may find the Treasury, the Post Office, the Secretariat General, the Land Registry and Mapping Office, the Directorate of the Interior and the City Hall. On the rue de La Grandière are located the Council of War, the Observatory, the Municipal Institution, the Central Telegraph Office, the Police Barracks, the Attorney General’s Office, the Law Courts and, a bit further along, the Prison.

Chettyar (Tamil) money changers in Saigon

The appearance of the streets of Saigon is very lively and curious; here live mixed populations from a range of different civilisations; French and other Europeans, Annamites, Chinese, Malays, Tagals and Indians – most of whom come from Pondicherry and Karaikal on the Coromandel coast – all elbow each other on the streets.

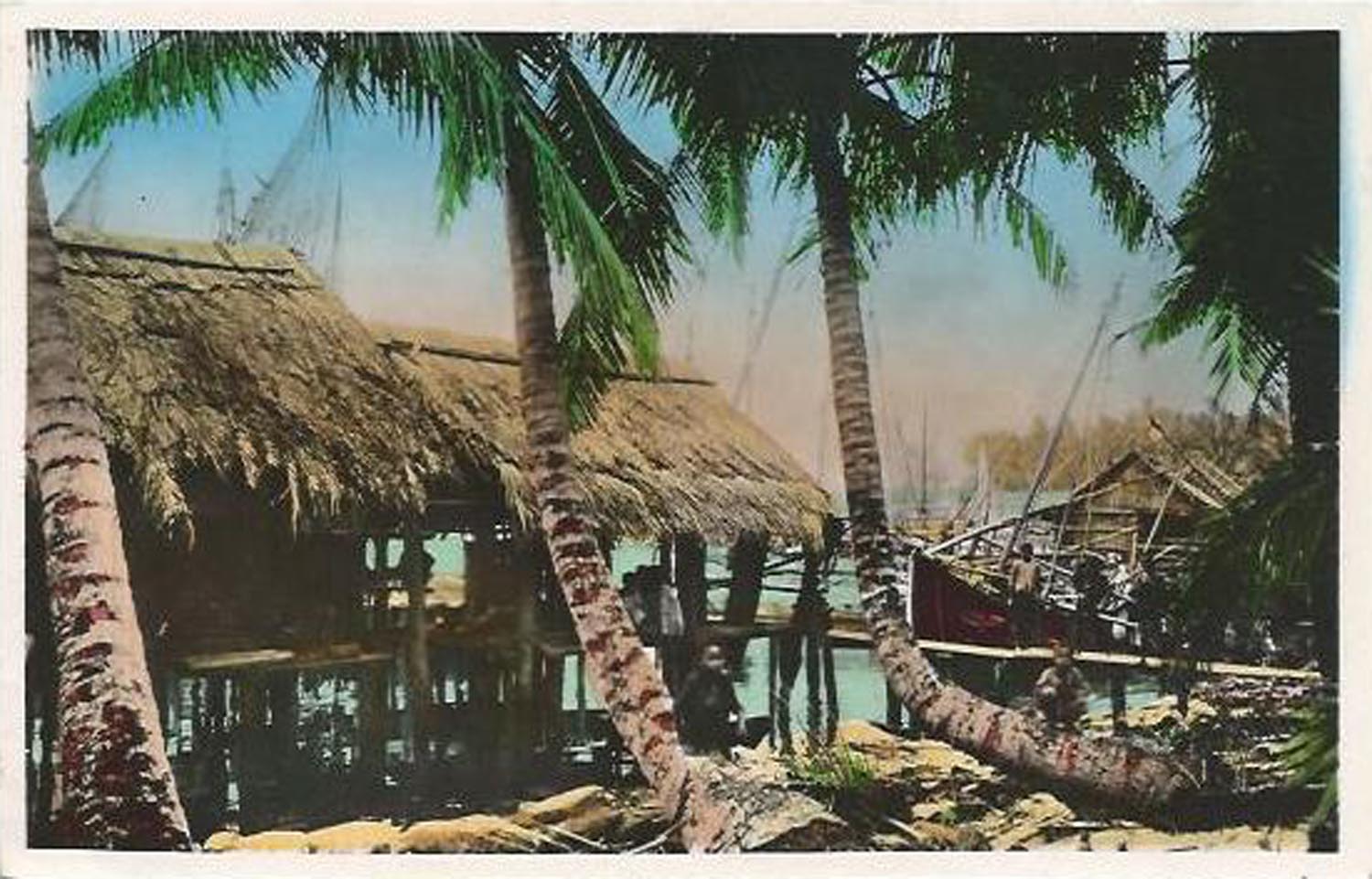

The indigenous population occupies the large suburbs, where it lives at will, building huts along the river, around the markets, or in the middle of small gardens with fruit trees. The Chinese, by preference, live in the lower part of the city, in the commercial areas, and most notably around the main market. The Indians are particularly fond of the areas surrounding the “High Road” to Cholon, the prison and the lower end of the route de Tongkéou [Cách mạng Tháng 8].

European traders are obliged to set up their shops and stores on the quayside or in the surrounding streets. As for government officials, they live mostly on the plateau which overlooks the Saigon river from a height of around 10m, in houses typically built with a front courtyard and a rear garden. The population of Saigon and its suburbs, including soldiers and sailors, government officials and the floating population, may be estimated at 65,000 to 70,000 souls.

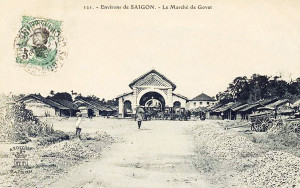

Gò Vấp Market in the late 19th century

The areas around Saigon offer the population many beautiful walks and pretty roads which, from 5pm each day, are lined with carriages; this is the time when one can go out without fear of sunstroke. Among the most popular are the roads to Cholon and to the big market at Go-Vap. The neighborhoods en route are populated largely by indigenous people who, having thrown their lot in with us from the beginning and having undergone the vicissitudes of conquest since the evacuation of Tourane, received a concession on the banks of the arroyo de l’Avalanche, between the second and third Avalanche bridges. On the left bank of the arroyo are large and rich villages such as Phu-Hoa and Hiep-Hoa, which provide Saigon with fruits and vegetables.

Leaving the market at Go-Vap and heading south, roughly parallel to the arroyo de l’Avalanche, one follows a magnificent route which, after the first Avalanche bridge, passes the buildings of the Inspection of Binh-Hoa, crosses the road to Hocmon, above the third Avalanche bridge, and continues as far as the route de Tongkéou, passing the tomb of Pigneau de Béhaine, the famous Bishop of Adran, author of the treaty of 1787 between France and Annam and advisor and friend to the Emperor Gia Long.

The Tomb of the Bishop of Adran in 1867

It was to this place, after the pacification of the country, that the bishop of Adran retired and cultivated a garden where he successfully grew the mangosteens he had brought from the islands of the Gulf of Siam. When Pigneau died in 1799, Gia Long gave him a magnificent funeral and ordered the construction, in the middle of Pigneau’s garden, of a funeral monument designed by a French architect in the style of a Cochinchinese pagoda. The tomb has always been respected by the local people, even when Annamite troops occupied the plain of Ky-Hoa in 1861. Later that same year, Admiral Charner declared the tomb to be national heritage.

One returns from the Tomb of the Bishop to Saigon [around 6km] by the route de Tongkéou, which crosses the Belt Canal, the famous lignes de Ky-Hoa, removed after the bloody struggle in 1861, and the arid and dusty Plain of Tombs.

2. Cholon

The city of Cholon is, after Saigon, the most important centre of the colony.

A street in Chợ Lớn

In 1778, a group of Chinese settlers, driven from My-Tho and Bien-Hoa by the invasion of the Tay-Son, came up the Tan-Binh river and founded, on a beautifully selected site, the city to which they gave the name Tai-Ngon. Through the activity and perseverance of the people, this soon became the most important commercial centre of the six provinces of Lower Cochinchina. The Annamites gave it the name Cholon, meaning “Big Market”.

The subsequent ban by the Annamite court on the export of all commodities other than rice, the edict which limited the number of Chinese, and the sumptuary laws which were applied to them, discouraged neither the skill nor the commercial genius of those hardy traders. These vexatious measures did not prevent them from building, at their own expense, stone piers over a length of several kilometres, and making a major contribution towards the upgrading of the canal connecting the Binh-Duong or Vam-Buc-Nghe [Bến Nghé creek] with the Ruot-Ngua which led to Rach-Cat [1819]. The Ruot-Ngua itself had been dug in 1772. At the same time, they completed the work of the arroyo de la Poste [Bảo Định canal], which was dug from 1755. From around 1820, Cholon became the necessary warehouse for all commodities of this rich region.

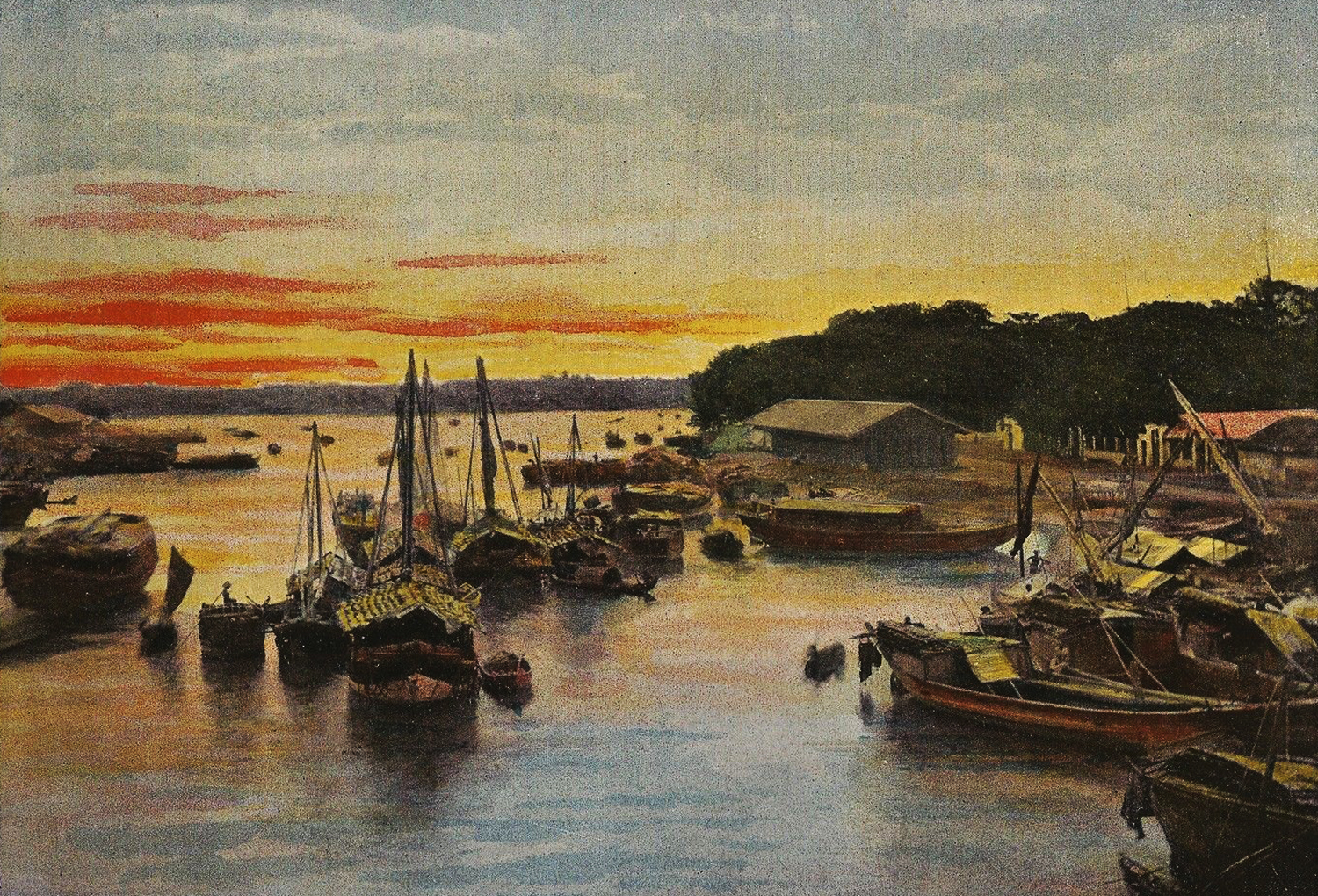

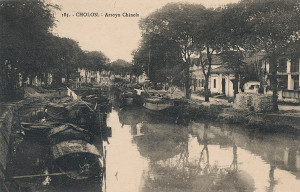

The Chợ Lớn creek (mislabelled “arroyo Chinois”)

The French occupation initially caused some apprehension among the Chinese merchants of Cholon, but the latter soon realised that it gave them more guarantees for the safety of their business, that they could forever be rid of the abuses of the authorities, and that it promised them the safeguard of equal law for all. Within a few years, the sphere of their transactions had increased tenfold.

Cholon is located 5km from Saigon at the crossroads of an ancient waterway, the Lo-Gom, and the canal which drains it into the arroyo Chinois. The city, regularly embellished and almost entirely rebuilt since our conquest, has quays of several kilometres in length, lined with houses of a beautiful appearance. Many bridges, raised high above the level of the quays to permit the junks and barges free circulation along the canals at any tide, give a unique aspect to this bustling city.

It is through the depot shops of Cholon that pass every year between 4 and 5 million piculs of rice for export; it is here that they are processed and placed in sacks to be taken to Saigon, so that steamships may convey them to China, Japan, Java, Singapore and Manila.

Junks on the arroyo Chinois in Chợ Lớn

Nothing could be more animated than the scenery to be enjoyed from the pont du Jaccaréo [once located near the modern Võ Văn Kiệt-Hải Thượng Lãn Ông junction]. The influx of junks, barges, sampans; in the background, the curtain of greenery around the Cây-Mai pagoda military post; and the docks where we see rushing and fussing labourers, compradors, dealers, store clerks and small merchants; all forming a striking ensemble on which those who still doubt the future of Cochinchina should reflect.

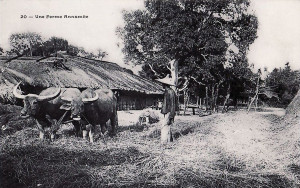

Out in the countryside, the aspect changes: there are retail stores, held by the Chinese if trade is important, and by Annamite women if the business is small. Among the shops belonging to grocers, fancy goods sellers, goldsmiths, restorers, pharmacists, tailors and food merchants, even those of the funeral directors and coffin manufacturers are no less pretty and elegant. Each store has at its door a sign with the merchant’s name in Chinese characters, artistically painted in black, red, blue or gold, according to the fortune or the whim of the master of the establishment.

The Fujianese Theatre in Chợ Lớn

At night, the shops of Cholon stay open. The streets, equipped with lamps which are lit by the municipality, are further illuminated by Chinese lanterns of the most varied shapes and colours, which bear in transparent letters the signs of the merchant. By this time, the hours of labour have ceased, making way for the hours of pleasure; crowds gather at the doors of Chinese theatres, and they all cram inside to attend the endless dramas that are the delight of this race, as eager for amusement as it is active and industrious.

Cholon has a population of at least 40,000 souls. The Chinese here are more numerous; the Annamite population seems to fear being absorbed by them, and tends to live far away from the noisy streets where traffic is too active. The city is regularly intersected by roads, all very neatly kept, and the French police have made the Chinese yield to our habits.

A beautiful market, paved in granite, occupies the centre of the city. One also notes nearby the very fine building constructed for the administrators of Indigenous Affairs.

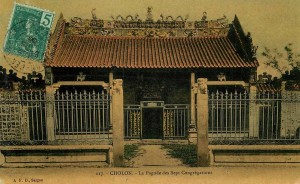

The Chinese have numerous very curious pagodas, among them that of the warrior gods and the Kouan-Chin-Whay, built by the congregation of Canton to the goddess Apho.

The “Pagoda of the Seven Congregations” in Chợ Lớn

The Chinese population of Cholon is divided between seven congregations which represent the different regions of China from which the Chinese settlers originate, each having its own customs and dialects. However, they agree among themselves, because they have adopted Annamite as their common language, and because ideographic writing is common to both the Annamites and the Chinese. A council of notables, chosen from various nationalities, operates under the direction of the first administrator, dealing with everything related to municipal interests. Cholon has a church, a pawn shop, an important school and a charity office.

There are two roads connecting Saigon with Cholon.

The first is the “Low Road” [route basse] or waterfront road, which follows the arroyo Chinois along its entire length. Half way along is the Choquan Hospital. The Low Road is intersected by several bridges, all in good condition, and offers throughout its course a most picturesque view of the arroyo. At high tide, the latter is covered by an infinity of vessels of all sizes – junks, barges, sampans and even canoes, the occupants of which row with equal quantities of animation and ardour.

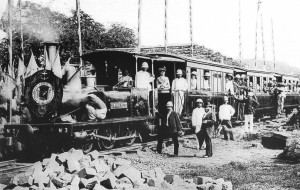

The opening of the Saigon-Chợ Lớn “High Road” tramway line in 1881

The second route, the route stratégique, is bordered, as it leaves Saigon, by European gardens, Chinese vegetable gardens and ancient Annamite gardens. It then passes the experimental farm known as the ferme des Mares, where one may see the remains of a royal pagoda, intended to perpetuate the memory of the illustrious men of the country. The route then continues to Cholon via the Plain of Tombs, the burial place of ancient Saigon. This plain is covered, over a distance of several kilometres, with brick or stone mounds; among them are some very remarkable monuments surrounded by high walls.

Cholon is also connected with Saigon by a steam tramway, which follows the old route stratégique and two paved roads.

3. My-Tho

My-Tho, capital of the district of the same name, and former capital of the Annamite province of Dinh-Tuong, is a very important town, both politically and commercially. It is located on the left bank of the northern branch of the Cambodian river, at the junction with the arroyo de la Poste. Formed from the two villages of Dieu-Hô and Dinh-Tao, My-Tho is located around 23 nautical miles by boat and 90km by land from Saigon, to which it will soon be connected by a railway line.

Mỹ Tho – boulevard Bourdais and the Inspection

My-Tho is the seat of an administrator of Indigenous Affairs and also has a courthouse. Its large Annamite citadel was transformed into a military barracks in 1877. Among the straw huts which line the quayside, one may also see many brick houses with tiled roofs.

The town also boasts a beautiful Catholic church, a first class medical clinic, a post and telegraph office, a treasury, a college, and a hospital for indigenous people. My-Tho has around 6,000 inhabitants.

4. Vinh-Long

Vinh-Long is the capital of the former province of the same name; the Annamites call it the “Garden of Cochinchina.” Vinh-Long is situated 26 nautical miles from My-Tho and occupies the angle formed by the Cochien and the Long-Ho, thus controlling the four arms of the Cambodian river.

Vĩnh Long – the quays

It is the place of residence of an administrator and the seat of a court; it also has a huge market and its port is frequented by many Annamite boats.

The city has a citadel, a military clinic, a post and telegraph office, a treasury and several important schools. Vinh-Long has around 5,000 inhabitants.

5. Chaudoc

Chaudoc is the capital of the district of the same name; it is the capital of the former Annamite province of An-Giang, and its citadel monitors the Cambodian border. Chaudoc communicates with Hatien by the Vinh-Te Canal and with the Mekong river by the Vinh-An Canal.

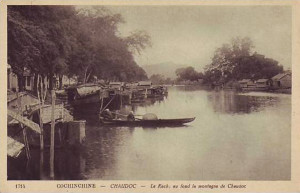

Châu Đốc – the creek at the foot of the mountain

It has a large market, an important military post, a citadel, an administrator’s residence, a courthouse, a post and telegraph office, a treasury and a clinic. Chau-doc has about 4,500 inhabitants.

6. Other Centres of Population

Most of Cochinchina’s other centres of population are the capitals of the various districts: Tay-Ninh, Thudaumot, Baria, Bien-Hoa, Tanan, Gocong, Bentré, Sadec, Long-Xuyen, Cantho, Hatien, Rach-Gia, Baclieu, Soctrang. Many date from the conquest and they are all expected to become more and more important in future.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.