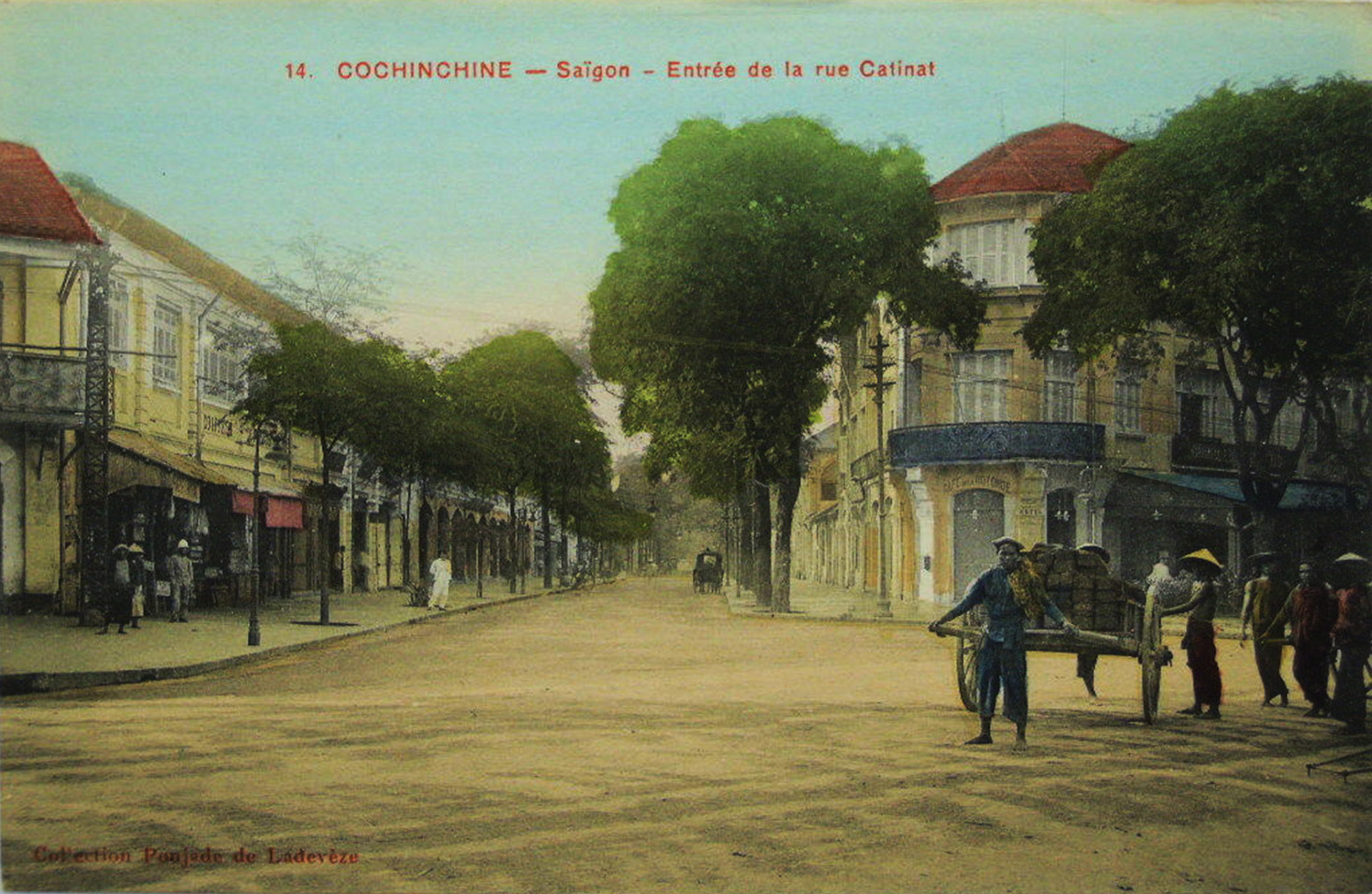

The lower end of Saigon’s rue Catinat

In 1899, en route for the Philippines, China and Japan, journalist and amateur photographer Henri Turot (1865-1922) toured Indochina as a guest of Governor General Paul Doumer. This translated excerpt from his 1901 book “Indo-Chine, Philippines, Chine, Japon: d’une gare à l’autre” (Indochina, Philippines, China, Japan, From One Station to Another) describes his short visit to Saigon and Chợ Lớn.

Two days of crossing, and another two days of hardship still separate us from Cochinchina!

What joy, therefore, when at about 3pm on 24 January 1899, land is sighted and the steep, wooded shores of Cap Saint-Jacques begin to grow on the horizon. It’s already too late for us to proceed up the Saigon River this afternoon, but the delay gives us the good fortune to spend a few enchanted hours at the Cap.

Cap Saint-Jacques (modern Vũng Tàu) with the Governor General’s villa in the foreground

The view is charming. Before us is a circle of wooded hills, surrounding a gracefully cut bay; the sun disappears and this sober but captivating landscape is bathed in red and purplish light.

In the foreground, at the centre of the bay, the simple and very elegant new villa of the governor general sets a cheerful tone amongst the green foliage.

We’re eager to go ashore, and after taking the first boat we are soon setting foot on the earth of Cochinchina.

Cap Saint-Jacques is really a most delightful place. Now under the leadership of the administrator M Outré, it’s a pleasant seaside resort to which colonial officials come from time to time to escape the oppressive heat of Saigon.

The family of the Governor General lives there for part of the year; they will soon take possession of the villa I mentioned above, which was completed during M Doumer’s trip to Paris, and inaugurated on the evening our arrival.

The Messageries maritimes vessel “Sydney,” pictured in Australia after 1895

Within hours, a lavish dinner is improvised. Most of the passengers of the Sydney gather at a luxurious table, around which well-groomed waiters circulate, silent and alert. M and Mme Doumer do the honours, surrounded by Admiral Courrejolles, Generals Borgnis-Desbordes and Delombre, and a retinue of officers of all ranks and functionaries of all levels.

It’s undoubtedly very flattering to sail in such distinguished company, but I would advise travellers who enjoy more exuberant crossings to choose a less official vessel.

We leave the dinner table, keen to take the delicious night air, which is far removed from the stifling evenings of Saigon. I take a long walk along by the sea, listening to the legitimate grievances of an engineer.

“What a shame,” says my interlocutor, “to have spent so many millions of Francs creating Saigon, while cap Saint-Jacques could so easily have become an admirable commercial port and a pleasantly situated capital. To stopover, ships wouldn’t have needed to waste four hours sailing up the Saigon river, which as you know is only navigable at high tide.” But what point is there lamenting past mistakes; let’s forget what might have been done, and concentrate only on the work which has already been accomplished – let’s go and see Saigon.

Chinese junks on the Saigon River

We leave at night. The river, which is navigable for ships of the largest tonnage, is winding and very wide; but the banks are monotonous and desolate, lined only with stunted mangroves in which large seabirds roost, uttering mournful cries.

Frequently we encounter large Annamite junks and small commercial steam vessels, few of which – alas! – carry the French flag.

Why, in our own colony, is cabotage in the hands of foreigners? The reason is simple, they tell me. Ships which navigate under the French flag, even in the Far East, are subject to French maritime registration requirements, that’s to say the entire crew – captain, sailors and mechanics – must be French.

Meanwhile, a vessel sailing under the German flag may have only a European master and an entirely Chinese crew. As a result, the costs for a German ship owner are much lower, and ships of that nationality may carry cargo at a more moderate price than ours; in fact, German ships transport much of our rice exports to Hong Kong and many Chinese ports.

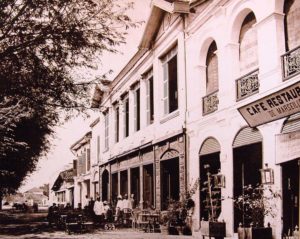

Saigon River waterfront cafés in the 1880s

For us, red tape; for the Germans, profit!

Alas! How many times during my trip have I noted our almost absolute lack of practicality, how completely helpless we seem to be in the face of the commercial activity and initiative of our competitors!

The view of Saigon offers some consolation; it really is a beautiful city, with wide boulevards, wide tree-lined avenues, beautiful walks and imposing palaces.

That of the Governor General is certainly the most beautiful building in the Far East. Its exterior has a grand air, and the ballroom and reception areas must impress all those who are admitted.

This is where M Doumer works with indefatigable perseverance, for the prosperity of our colony.

His efforts have already been rewarded with valuable results, and the fiscal situation is now improving every day; at the same time, under his energetic impulse, officials of all grades are working far more efficiently.

By the way, let me do justice to a man who was so passionately attacked for some time – I speak of M de Lanessan.

Governor General Paul Doumer

Certainly, the work of M Doumer is considerable; thanks to him, Indochina has attained the homogeneity and unity indispensable for its development; thanks to his skill and firmness, pacification is almost complete in all parts of our Indochina possessions; thanks to the boldness of his ideas, and to the confidence they inspire, a railway network soon will connect the main centres of exploitation to the coast; and thanks finally to the authority he has been able to exert over all around him, military leaders dare not enter into conflict with our civil power.

But it would be fair to extend to M Lanessan a large part of the praise given to his successor (here, I do not forget that M Rousseau’s administration stands between that of M Lanessan and M Doumer, but its action was almost nil).

Everyone in Indochina has excellent memories of the current Minister of the Navy, and I have heard many talking about his foresight and achievements; it was indeed he who began the task which has been continued so well by M Doumer.

Unfortunately, neither man was able to improve the state of sanitation in Saigon, which still leaves much to be desired.

One is painfully impressed on landing by the sight of the city’s emaciated, anemic and pallid colons. In fact, this is due not so much to the hateful climate than to the imprudence of the Saïgonnais. Nowhere, in fact, have I ever seen anyone absorb absinthe in such huge quantities; day and night, the cafes are full of consumers who imbibe horrible “purees” of the stuff on ice.

Absinthe time at the Hôtel des Nations bar-restaurant

Everywhere, alcohol can be harmful, but here in the tropics, it is especially dangerous, and the pavement cafes of the rue Catinat are certainly more deadly than the rays of the merciless sun, or the pestilential miasmas of the swamps.

Anyhow, let’s go in search of a refreshing breeze on the “Tour de l’Inspection,” the elegant promenade plied by so many Victorias, those dainty English carriages which convey Annamite “congayes” in bright dresses.

On our return journey, we travel through the Botanical Gardens, which are quite pretty, with green lawns, shady trees and small lakes with still waters.

The day is at an end. All that’s left is to go back to the stuffy hotel room and commence that nocturnal combat – unequal and certainly lacking glory – with greedy mosquitoes, tempted by the intact skin of the newcomer.

In Saigon, distractions are rare, and the tourist has little to relieve the despondency which so quickly descends on him, other than the choice of the two promenades: Cholon and the Tour de l’Inspection.

Cholon is half an hour by carriage, and anyone visiting it for the first time is amazed to find himself suddenly transported into a Chinese city.

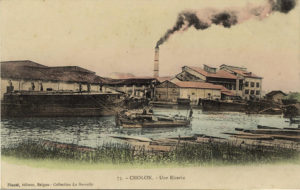

A rice husking factory in Chợ Lớn

In all of the Far East, Cholon is the city where the most enormous quantities of rice are concentrated, a place to which thousands of sampans come every year. The quaysides along its canals are cluttered with bulging sacks, and there’s always a great swarm of workers connecting the sampans with the dehusking factories, whose great buildings extend over a length of several kilometres.

These factories are, for the most part, the property of rich Chinese businessmen, millionaires several times over, who adopt without any difficulty, in fact one could say with great haste, all industrial improvements and all the most modern processes.

Dare I mention that, even in the exercise of worship, the Chinese seem to apply scientific progress?

In one of the Chinese factories I visit, I wait for the owner in a vast hall equipped with simple carved furniture but sumptuously decorated with red silk hangings bearing sacred inscriptions in black characters. At the back, as in all Chinese homes, a potbellied Buddha sits on an altar, surrounded by tall candles and decorated with many beautiful fruit filled trays. Look closer at the candles and you’ll see that they are in fact made from pieces of long metal tube, painted white to resemble wax, with a small flame-shaped flashlight at the end.

A commercial street in Chợ Lớn (MAP)

A Buddha illuminated by electric light! This is the first time I’ve seen this, which leaves me surprised and perhaps even a little jealous that their worshipping practices have been so perfected, while the Christian god is honoured in our churches only with simple candles and oil lamps.

In the evening, the animation in Cholon is extraordinary. The shops are all illuminated by large red lanterns, and the narrow streets are crisscrossed by Chinese, who trot along, each carrying a small lamp.

While in Cholon, it’s essential to pay a short visit to the Annamite and Chinese theatres, which, incidentally, have much analogy with each other. The Annamite theatre features actors in embroidered costumes who contort their hands and feet in extravagant gestures and utter furious cries as they attempt to be heard over the infernal din of gongs and cymbals. It’s quite impossible for me to understand the plot, which the local spectators follow with an attention unfamiliar to the French public.

The noise level in the Chinese theatre is no less astonishing, but the actors there scream their sentences alternately with the din of the instruments. They use actions and gestures to convey the general sense of the drama: two warriors are at war for the sake of a beauty. A beauty? In fact, she is represented here by a man (Chinese women do not perform on stage) who is made up in a very clever way and plays the part with a very shrill tone, of which my eardrums tire very quickly.

An outdoor theatre performance

I still can’t understand why oriental drama remains so rudimentary when are thousands of learned scholars who are capable of creating more complex works.

A curiosity of Cholon is the elegant mansion of the Phu (prefect), where lovers of culinary peculiarities will be initiated into the complicated mysteries of Annamite cuisine.

The Phu also has two very sweet daughters, each with her own story to tell.

One was formerly in love with a young officer who died unexpectedly before the nuptials, and whose tomb is piously maintained by the Phu. The other had the good fortune to attract the attention of the young Emperor of Annam when he came to Saigon to visit Governor General Paul Doumer. It’s said that at nightfall, the Asian sovereign jumped over the wall of the palace, where he had been offered rather formal hospitality, and made his way to Cholon to engage, under the window of the Phu’s daughter, in manifestations incompatible with royal majesty. M Doumer, who does not take such matters lightly, was called to come and put things right.

Incidentally, I set myself the task of solving a problem I have often asked myself. It seems that not all Annamite women conform to our western ideals of feminine beauty; by reciprocity, are Annamite men indifferent to the charms of European women?

A horse and carriage about to leave for the Tour de l’Inspection

After taking notes, I can affirm that they are not. Indeed, I should mention that, while attending the grand balls of the Governor General, the afore-mentioned Emperor of Annam, far from being completely absorbed with his love for the daughter of the Phu, did not hide his admiration for the buxom charms of M Doumer’s French women guests.

But let’s return to that famous promenade to the Inspectorate, of which I have already spoken.

This is where married French women and Annamite “congayes” strut around in glamorous costumes, for which husbands and lovers are forced to pay, often with some difficulty.

Because money is scarce in Saigon! And officials who fall into debt must pay dearly on the loans they are forced to contract.

Here you can incur interest of 12% on a first mortgage, while loans agreed by simple signature can attract fantastic rates which may reach as much as 60-80%. Is this not an indicator of the shortage of capital, and is it not regrettable to note that, while millions and millions of Francs sleep in France, hidden either in stockings under the bed or in the safes of the major credit institutions, our colony in the Far East is floundering for lack of cash?

But nothing can defeat the pusillanimity of French capitalists, who waste no time assessing the purchase of government bonds as an unwise investment!

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.