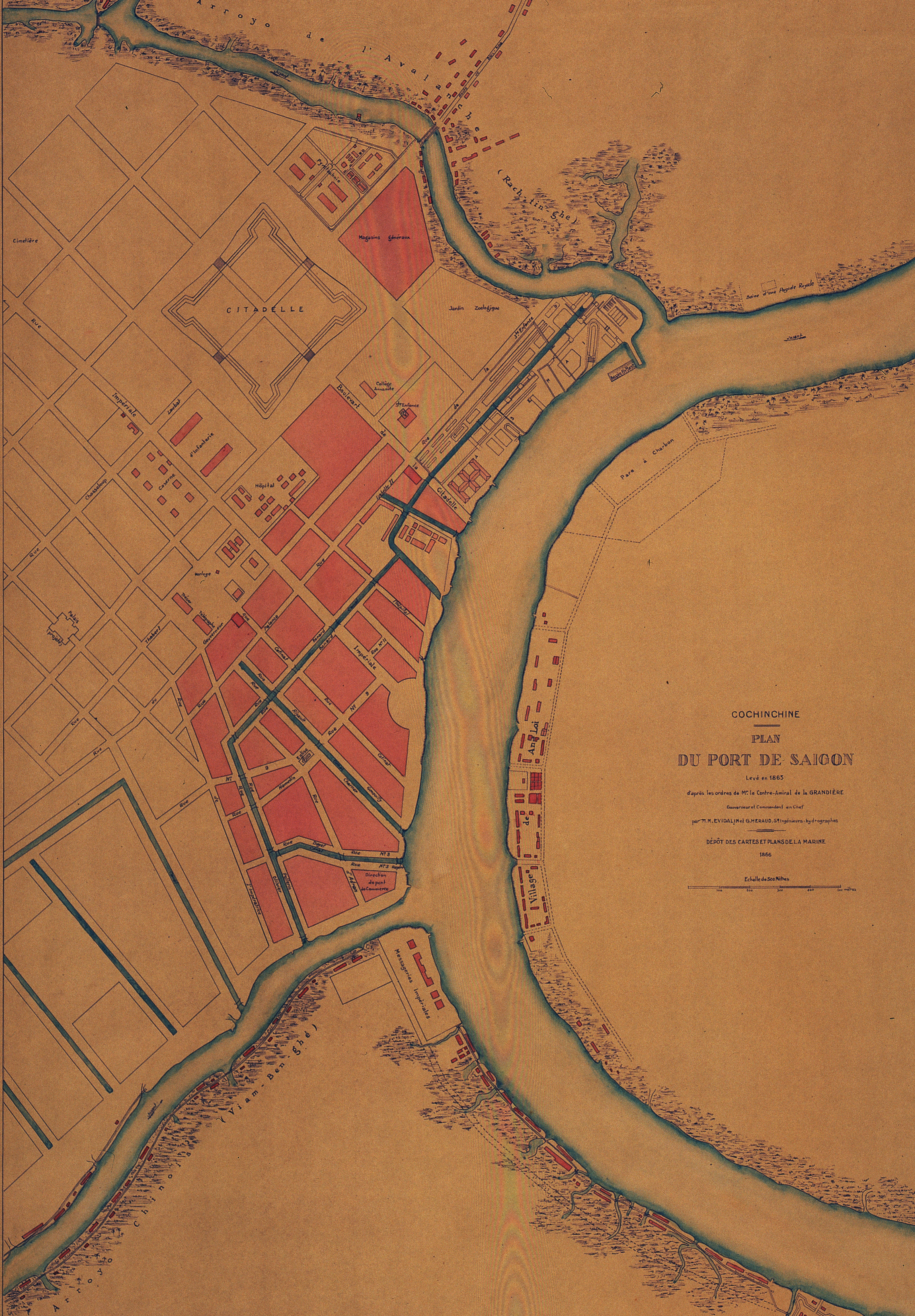

Saigon in 1863 (MAP)

Tainted throughout with the usual colonial racist arrogance, Artillery Lieutenant P C Richard’s account of Saigon just a few years after the French conquest, “Saigon et ses Environs au Commencement de 1866,” written for the Revue maritime et colonial of September-December 1866, nonetheless contains some interesting observations about the city during that period.

Saigon

Since our victorious arms completed the conquest of a part of Lower Cochinchina, many in France have been occupied with this corner of Asia, a region hitherto virtually ignored. However, although many documents have already been published about this country, our new colonial capital of Saigon is little known and has not yet been described in a comprehensive manner. We do not pretend to fill this gap here, but will nevertheless say a few words about this city and then on its surrounding areas.

The Messageries impériales headquarters

The capital of French Cochinchina is located on one of the arms of the Donaï, called the Saigon river, and located at the north-north-east extremity of a vast alluvial country, an immense delta barely raised above sea level, and crossed by numerous mouths of the Donaï, the Soirap and the Cambodia rivers. Here one finds many arroyos (waterways) which, projecting in all directions, form many routes favoured by the tide, which is felt far inland in territories which it waters twice daily.

This city is located entirely on the right bank of the river and the left bank of the arroyo Chinois [Bến Nghé creek], 100km from the sea. It is protected downstream by a fortress known as the Fort du Sud, and defended in the north, next to the plain, by a citadel built by French engineers.

This place is very well situated for defence. It is enclosed in a quadrilateral which has for its sides the Saigon river to the east, the arroyo Chinois to the south, the arroyo de l’Avalanche [Thị Nghè creek] to the north, and a canal that links the latter two arroyos to the west. It is quite safe from attack. It could perhaps be attacked by water, but it is connected with the sea via a long river of 25 leagues. This river is sinuous and very easily defended by fortresses, which, appropriately placed and armed with our formidable engines of destruction, would deter all enemy fleets.

Ships on the Saigon River in 1868

Located between India on the one hand, and China and Japan on the other, this city has a military and strategic importance which is undeniable. Foreigners know that well, and today, not without jealousy, they call it “the French Singapore.”

Moored in front of the city is a fleet of warships, grouped around the Duperré, a ship with two decks which flies the flag of the Vice-Admiral Governor and Commander in Chief of our troops. Further down, between Saigon and the Fort du Sud, one may find the commercial port, where elegant European vessels lie at anchor alongside massive Annamite or Cambodian boats and Chinese junks, all richly coloured and decorated with fantastic dragons, which give the port a very picturesque appearance.

Nothing is more curious to observe than the junks of the great Annamite mandarins, who come from time to time to salute our Governor, and who, in such circumstances, deploy all the oriental pomp of which they are capable. We love to see their shiny spearheads, their tridents and their peacock feathers, all hallmarks of the royal official. We love to see those who we fought so recently coming quietly and humbly now to bow beneath our tricolour. A doleful-sounding drum may be heard from time to time during these processions, giving each a certain imposing and almost majestic je ne sais quoi.

“Saigon – Literati come to salute the Governor”

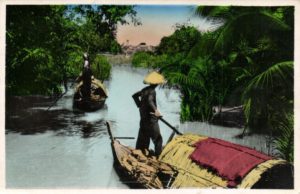

Here we see a real floating city; the quays are lined and the harbour is constantly filled with junks and sampans; the latter are made from tree trunks carved and shaped by the Annamites, just like the canoes built by the Gauls out of the trunks of huge oak trees from their beautiful forests. These sampans have a singular form; in the middle there is a cabin covered in palm leaves, where may be found all the utensils of the Annamite kitchen – because the boatman is born, lives, suffers and dies on his boat. Each end of the boat is raised and it is there that one finds the rowers, usually women, who stand, facing forward.

Some of the larger boats, junks, for example, are equipped with sails made with coarse mats, which are manufactured either from coconut leaves or from rushes. Such junks are filled with many families, who often have no other place of habitation.

In neighbourhoods inhabited by Annamite people, generally located far from the centre of the city, there is usually a large population. Until they reach the age of 12 or 14, children of both sexes live an unfettered life, wallowing in mud or rolling in the dust.

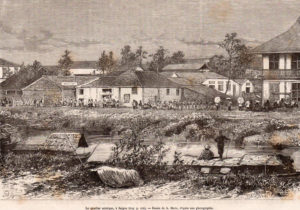

The “Asiatic quarter” of Saigon in 1875 (engraving)

Those who took part in the conquest of Saigon will certainly no longer recognise the poor Annamite town of yesteryear. Where there were once wretched huts set amid stinking marshes, there are now pretty houses bordered by beautiful boulevards. All that’s lacking now is the cool shade of beautiful trees which we will enjoy one day in the future when those already planted have grown sufficiently to intercept the sunlight. The ugly wooden huts that once lined the right and left banks of the arroyo Chinois, before which one could not pass without being inconvenienced by the nausea-inducing smell of nuoc-mam (a sort of brine made with rotten fish which is used to spice Annamite dishes), have now disappeared to make way for the pretty quai Napoleon [now Tôn Đức Thắng], which is around 50m wide, is divided into sandy paths and flowerbeds, and is bordered by lawns planted with trees. The perfectly aligned shop houses of our principal traders are located along one side of this pleasant boulevard, which is also adorned with a column raised by Saigon traders in memory of one of the first French administrators.

On the other side of the arroyo Chinois, the beautiful buildings of the Messageries Impériales form a nice area which at present, unfortunately, may only be accessed from the city by boat.

The former Grand Canal in Saigon

Canals criss-cross the city and facilitate the movement of merchant traders. Large boats enter them and carry their loads directly to the storefronts and markets.

Wide boulevards, roads and bridges, hitherto unknown in Cochinchina, allow horse-drawn carriages easily to reach places where previously one could not even circulate on foot without sinking deep into the mud.

It’s truly a pleasure to see the horse-drawn carriages of our colons pass quickly between heavy old freight carts of primitive construction, each of their solid wheels cut from one piece of a tree trunk. Those gaudy vehicles, with bells and whistles attached to the ends of their shafts, are hauled by a special breed of buffalo from Cambodia known as “runner buffalo,” which can trot and even gallop. The resulting cacophony is capable of offending the eardrums of the less delicate.

We may still encounter in Saigon some remains of ancient Buddhist monuments, among others a very pretty little pagoda located right in the middle of the city, which will soon to be an object of curiosity dear to archaeologists, because Annamite monuments disappear very quickly to make way for private houses.

Let’s now visit Saigon’s public buildings and facilities.

Saigon’s first purpose-built cathedral, the Église Sainte-Marie-Immaculée (Church of Saint Mary of the Immaculate Conception).

Our Cathedral is of a modest size which hardly does justice to its grand title. But it has the distinct honour of being the first Christian church built on this land, which for so long was vested with the coarsest and most stultifying paganism. The Cathedral was once surrounded only by small huts inhabited by miserable individuals who had taken refuge here under the sign of the cross, but today it is already dwarfed by the buildings that surround it. The need for a larger church now arises, because many Annamite Catholics are only able to attend its services by standing outside.

The Hôtel du gouvernement (Governor’s Palace) is also very modest. A replacement, more worthy of its function and of the capital of our new settlement, is being planned.

The Imprimerie imperial (Imperial Printing Office), located near the Governor’s Palace, offers nothing remarkable.

The Hôtel de la Direction de l’intérieur (Internal Affairs Office) is newly completed and occupied; it is a grand and well-ventilated building.

The first Governor’s Palace

Another government building which certainly will not lack residents has also just been completed. I refer, of course, to our new Maison centrale (City Prison), where prisoners are certainly better housed, and better fed and cared for than some of their free countrymen. We have neglected nothing to soften their captivity; and many of the inmates here may well enjoy a comfort they cannot experience at home.

The Direction de l’artillerie (Artillery Directorate) of the Navy and the Colonies, soon to be completed, deserves special mention.

The site it occupies was once a vast muddy swamp, crossed by several rivers. We had to fill this to create a large area of solid ground on which buildings could be constructed. Thanks to our powerful impulse and intelligent management, the marshes and streams vanished, piles were dug, and large workshops were built, all of which now function perfectly.

Soon these workshops will be equipped with that most powerful agent of modern industry – the steam engine. Thus will be achieved the laudable goal ardently pursued by senior officers who have successively commanded this institution, to equip our young colony with an Artillery Directorate worthy of the great role France can be expected to play in Far East.

The personnel of the Director of the Arsenal in 1875

A canal, each end of which communicates with the Saigon river, runs through this facility and facilitates the transport of equipment and ammunition for the French fleets of China, Japan and Cochinchina.

The Artillery has a spacious, well ventilated barracks building, thus far the only one in Saigon, because one can hardly give the name “barracks” to the poor huts of the Camp des Lettrés (Camp of the Literati, Trường Thi), which currently house our marine infantry.

Officer housing, especially the villa of the Director of Artillery which is very well located on a plateau, is deemed more spacious and better ventilated. It is thus more suitable to climatic requirements and therefore, at present, the safest housing in Saigon.

The Direction des constructions navales (Naval Construction Directorate) must be placed first among the institutions of our new colony. It occupies a large compound which is 1km in length with an average width of 250m, located at the junction of the Saigon river and the arroyo de l’Avalanche; it is separated from the Artillery Directorate by a rectangle of about 300m long and about 150m wide which will house our future naval stores.

Saigon port in the 1860s

This establishment is already functioning. A canal facilitates water-borne transport of large amounts of wood from the forests of Tay-Ninh, the Central Highlands and Cambodia, into facilities where they can be put to use.

A small dry dock, 72m in length and 24m wide, can repair and clean small gunboats and other ships with a draft of less than 4m. However, surveys we have made in the land of the Directorate indicate that there is plenty of space in which to build a much larger dry dock. While we wait for that dock to be built, we have just installed and launched a floating dock, which will save us from having to send our great ships for repair in Hong Kong, Singapore, or Bombay. Our great frigate Persévérante was placed in this floating dock on 8 August last.

Saigon, becoming the tète de ligne of the Messageries Impériales, is bound to grow in importance.

Thus will be fulfilled the wish expressed by M Guizot, who, when he was foreign minister, exclaimed, “We must not, in case of damage, send our ships for repair in the Portuguese colony of Macau, in the English port of Hong Kong, or in the arsenal of Cavite on the Spanish island of Luzon.”

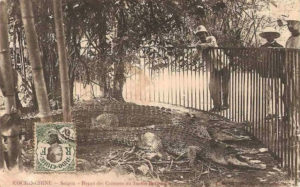

A corner of the Botanical and Zoological Gardens

The Zoological and Botanical Garden is close to the Naval Construction Directorate, from which it is separated by a boulevard. Here one’s eyes may rest pleasantly on the trees which have recently been planted. Beside the native species of recognised utility, one may find here other no less useful varieties from Réunion, Singapore, Batavia, etc. The breadfruit tree is the subject of a special predilection by the director of this institution, and promises to endow the colony with a fruit superior to the native jackfruit.

A swamp covered with water lily, lotus and other aquatic plants is inhabited by wading birds such as cranes pelicans, egrets and ibis.

After the field of waders comes the park of the ruminants and the aviaries which contain many of Cochinchina’s most beautiful birds; in the latter, we have already collected peacocks, pheasants, green pigeons and doves.

A palace has been built here for the colony’s different species of quadrupeds. There is a long line of cages for wild animals which already contain a civet, a porcupine, a wild boar, a wild cat and a young tiger of the most beautiful species.

A crocodile enclosure in the Botanical and Zoological Gardens

A crocodile is enclosed in a small fenced park, through which a stream flows.

A large garden area, planted with beautiful trees, bushes and flowerbeds, is intersected by well shaded pathways, offering visitors a pleasant walk alongside the arroyo de l’Avalanche.

North of the garden are located the general stores, where large supplies of rice are kept. The rice is brought by ship from all parts of Cochinchina. It was in one of its huge buildings in February 1866 that our colony hosted its first agricultural and industrial exhibition, the results of which were impressive.

We are pleasantly surprised when we enter the lovely Parc de l’Espérance (“Hope Park”), with its abundant fruit trees and amenities. Once the home of mandarins travelling in the service of the emperor of Annam, this park was given to the Artillery of the Navy, which established here its ammunition and gunpowder stores and ateliers. This would be an excellent place to build a barracks. The scene here is very animated, with sampans and river boats gliding along the nearby arroyo de l’Avalanche, and birds twittering on flowering or fruit-laden evergreens.

Now let’s visit the city’s religious institutions.

One of Saigon’s earliest schools

The Collège des Missions (College of the Missions) is built almost in the Greek style, with oriental ornamentation.

While visiting this place, where we may already find many Annamite students being taught by the Fathers, let’s pay a tribute of praise to our missionaries, those intrepid pioneers of civilisation who, listening only to their zeal, left their country, their friends and family to traverse immense seas and arid deserts, to reach countries devoted to idolatry. There they raised the holy cross, that symbol of faith so comforting to the poor and unfortunate, teaching them that Christ was born poor, lived poor and died persecuted. Thanks to the work of these courageous apostles, who fought so hard for all nations to break their idols and submit to the Gospel, we have responded to the cries of our martyrs by conquering Lower Cochinchina and opening the doors to the Far East.

Mingling without fear with the native people, our missionaries acquired considerable influence over them. They learned the Annamite language and translated into that language passages of Holy Scripture, hymns, psalms and prayers, all of which are now repeated in chorus by converts in a manner which is strange and monotonous to hear. Thanks to the zeal of our missionaries, superstition and belief in evil spirits is gradually giving way to the civilising dogma of Christianity.

A pousse-pousse station

Next door to the College of Missions is the École française de l’évêque d’Adran (Bishop of Adran School), a very useful institution founded on 21 September 1861 by the fertile mind of the first Admiral who landed in Saigon. This officer quickly recognised that, in order to assimilate the local people, it was necessary to disseminate French education, language and customs among them. He also realised that it would be a mortal blow to the influence of the old literary mandarins if, using our Latin characters, the children of local people could learn within months the science which scholars had devoted all their life to acquire. The Admiral Governor saw in this school a nursery for the dedicated public servants of the future, who knew the laws, manners and customs of the country, and had been called to render great service to our colony.

Already, students who can read fluently their own language printed in Latin characters will soon be able to write it too. Many can now read French, and a few are beginning to understand and speak it. Thanks to the care of our government, schools have been established in various locations, and students, showing great intelligence and ability, have made significant progress.

At the riverside

It must be said that the beginnings of this institution were rather painful. The population, newly conquered and unaccustomed to care from their own rulers, did not, even could not, understand an idea so generous as this. Also, the first calls made to parents to send their children to this school were suspected of being a method of military recruitment; traditional village chiefs raised children for service as we raise a tax, and parents of recruitees received a certain sum as compensation, so that far from paying for the instruction of their children, they were instead used to paying for them to remain uninstructed.

But things have changed since that time, and shortly after the creation of this institution, increasing pressure for places meant that the school had to be enlarged. The families of notables now strongly solicit the admission of their children as a favour and honour and now, despite the efforts of the administration, the school is not large enough to meet demand.

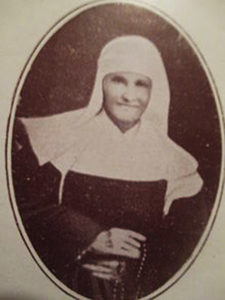

Carmelite nuns

In front of the College of Missions is a house of dark appearance with only one opening, topped by a small stone cross which is already blackened by time. This house contains the Carmelites, who came in Cochinchina to devote themselves to the contemplative life and to pray, suffer and die here. Despite the austerity of their regime, we find amongst the Carmelite Order several indigenous postulants who aspire to the happiness of becoming the mystical brides of Christ. Already some have been deemed worthy enough to don the humble clothes of penance, and have traded the joy of almost unlimited freedom enjoyed by Annamite women for absolute seclusion.

Let’s leave those cloisters and have the pleasure of visiting the beautiful convent of Saint-Enfance and its delicious small chapel, topped by an elegant spire which dominates the entire countryside and announces to travellers the capital of oriental France. A cross crowns this edifice, and the French flag flying next door appears to protect this sacred sign of our civilisation.

The architecture of the convent recalls that of Italy, blended with the caprices of Annamite ornamentation. The chapel, in Gothic style, is bedecked with paintings of questionable taste, which will surely soon be devastated by the weather and the rain.

The Sainte-Enfance in the 1870s

All this is the work of an Annamite priest from Tonkin, an improvised architect without any training in that field, who designed and executed the plan of this beautiful establishment, in his own words, for the greater glory of God. “Faith moves mountains!”

Let’s say a few words about this institution.

The institution of Sainte Enfance, the most useful, the most moral and the most charitable that we have in Cochinchina, was founded in 1861 by the virtuous and courageous Sisters of Saint-Paul de Chartres and under the high patronage of Her Majesty the Empress of the French, the consoler of so many afflicted, the mother of so many abandoned; This refuge is open not only to orphans, but also to all unfortunate children, regardless of the religion of their parents.

The nuns receive small poor abandoned creatures found by police, soldiers and sailors on their rounds or during their excursions, as well as those brought by infirm fathers, widows deprived of resources, or grandparents unable to feed their young orphaned grandchildren. Here we may find many poor little creatures, abandoned but without doubt well advised, who came to knock at the door of the asylum.

Reverend Mother Superior Benjamin (1821-1883), founder of the Sainte Enfance in Saigon

Orphans who survived the war, children of victims of Bien-Hoa, Baria and Go-Cong, have found here the arms of charity open to receive them and have not been neglected. Thanks to the care of the resident nuns, all these children are now clean and tidy, learning to count, read and write in French. The girls are trained in needlework and initiated in household care, order and cleanliness, while the boys work in the garden and make and mend their own garments. These children also used their leisure time in the manufacture of cigars made with tobacco from Cochinchina.

Later, when these kids grow up, they will be capable of earning an honest living. The girls will be free either to leave or to remain in the convent, because the Sainte-Enfance now also has indigenous novices, postulants and even sisters.

Apart from the children abandoned or brought here by their parents, the ladies of Saint-Paul de Chartres also run a pensionnat or boarding school, which receives students who pay for their maintenance, care and instruction. This school currently draws on the local budget to the tune of 24,000 francs, which is divided into 100 scholarships and increases or decreases according to the number of students.

The pensionnat is also open to children of Europeans (girls) and offers, for a relatively low price, an elementary education, religious and moral education and loving care.

A clinic run by the sisters of Saint-Paul de Chartres

We must still visit an establishment which casts over our thoughts a dark veil of sadness; This is the Thi-Nghe Clinic, truly an asylum of suffering and pain! Here, as everywhere, we find the sweetness, self denial, boundless beneficence and sublime charity of the nuns of Saint-Paul de Chartres, who are always on hand at the bedside, encourage patients with soft words and calming their despair with their touching care!

What heart would not be moved at the sight of these sublime women, who dedicate their lives to the relief of human suffering! They are truly admirable and holy women, real angels of charity, whose delicate hands mend physical injuries, while their soft voices, echoes of a heart overflowing, and their chaste glances, often veiled in tears, heal spiritual wounds.

The outlying districts of Saigon

Now let’s leave Saigon and take a promenade outside the city.

Travelling along the left (north) bank of the arroyo Chinois, we follow a long populated and very lively quayside, which is lined with huts on each side. Those located on the side of the arroyo are literally in the water, which penetrates them at high tide. These huts make up the 12 villages of Cau-ong-lanh (Cau being the Annamite word for bridge), Cau-mui, Cau-khom, Cau-kho, Cau-ba-tim, Chu-Sao, Cau-ba-do, Cau-moï, Cho-quan, Binh-yen, Khanh-hoï and Vinh-hoï; the latter two are on the right bank of the arroyo.

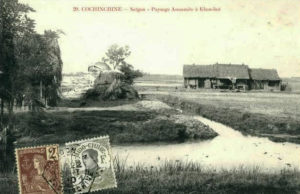

Gia Định countryside

All of these villages are inhabited by Annamites who fled during the conquest and returned later, titles in hand, to reclaim their properties. We hasten to add that the French administration upheld their claims and reinstated them in Saigon.

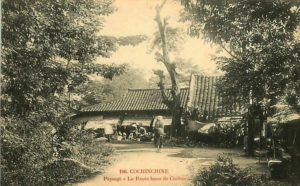

Ten of these villages are suburbs of Saigon, while the other two are suburbs of Cholon (Chinatown) as they connect the two cities. We will stop leisurely at one of these villages, Cho-quan, which occupies roughly the middle point between the two cities and resembles a large garden, with its huts shaded by tamarind, mango, areca, coconut, papaya, banana, grapefruit, orange, jackfruit, breadfruit and mahogany trees, flame trees and many other species. Around their trunks climb golden betel leaves and beautiful lianas with dangling berries which dance in the breeze above the heads of the numerous noisy and almost naked children of both sexes who play in the fresh gardens.

The huts, well kept, thinly scattered and surrounded by well-cultivated gardens, are connected to each other by pretty pathways lined with euphorbicaea and other flowering shrubs, which perfume the air and delight the eye.

A waterway in the environs of Saigon

The people of Cho-quan are Christians. They live a modest life of relative ease, making silks, cottons and small furniture inlaid with mother of pearl; but their main industry is the smelting of copper, bronze and even gold and silver, which they turn into jewelry.

This village has a church and a large hospital; the latter, long assigned to sick members of the Expeditionary Corps, has now been delivered to the service of indigenous patients, who may find there the sweet care of the sisters of Saint-Paul de Chartres and the medical skill of the naval surgeons attached to the property.

Since we have left the banks of the arroyo for an excursion in the gardens of Cho-quan, we will continue along this road as far as the Mares (Ponds). There is a pagoda here, one of two on the site which we call the Pagode des Mares (Pagoda of the Ponds), because of the two small pools located in front of its enclosure. It is known by the natives as the Pagode de la fidélité éclatante (“Pagoda of brilliant loyalty”) and was originally a kind of Annamite Panthéon containing the ancestral tablets of great men.

Khánh Hội landscape

Among those were the ancestral tablets of a Frenchman, a Breton sailor named Manuel, named Men-oe by the Annamites. However, since our conquest of the country, the residents have erased the characters inscribed on those tablets, so we can no longer know the deeds and titles of this brave sailor, once a fleet commander of Gia-Long, whose cause he had embraced. All we know of our illustrious compatriot is that the prince he served rewarded him with many lavish titles and honours, and that he died gloriously in a naval battle by blowing himself up with his warship rather than surrendering to the Tay-Son. These rebels, as we know, were defeated at the beginning of the 19th century.

Before the conquest, old invalid monks were responsible for the maintenance of the pagoda, as well as the magnificent tombs of the great men which surrounded it. They were responsible for offering sacrifices to the spirits of these heroes, the guardian gods of Cochinchina.

Alas, due to the sad effect of the war, this pagoda is now used as a gunpowder store, and its outbuildings are used as a barracks. The surrounding land, where there are so many beautiful funeral monuments, has been transformed into a meadow where the artillery takes its fodder, but there are still many beautiful trees here, making it a very pleasant site.

On the road to Chợ Lớn

On the edges of the road from Saigon to Cholon which runs through the plain, we may see great and very rare fruit trees, whose magnificent pear-shaped fruits contain a sticky, clear edible substance which, when cooked, produces a kind of jam which tastes like honey, and of which the Annamites are very fond.

The pagoda is surrounded by tall trees with straight and slender trunks. In a normal breeze, their branches emit sighs like plaintive whispers which recall the noise of small waves as they come ashore on a smooth beach; but if the wind blows more strongly, the same branches emit lugubrious groans, similar to the distant sounds of an angry sea smashing its waves against the rocks. In recent years, hearing such noises, superstitious and frightened Annamites living in the neighbourhood have redoubled their offerings and sacrifices, believing the noises to be angry threats from spirits that we have driven from the pagoda.

All these spirits have their own legends, some quite frightening, which old men recount at night, lying on the mat, surrounded by their children and grandchildren who listen, trembling.

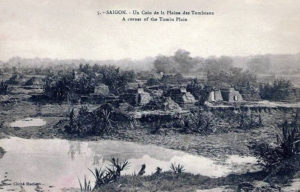

Tombs on the plain between Saigon and Chợ Lớn

One of the dependencies of the pagoda and nearly half of its enclosure have been devoted to the establishment of a stud farm, whose management has been entrusted to a cavalry officer thoroughly acquainted with equestrian science.

To the north of the Mares is the wide Plaine des Tombeaux (Plain of Tombs), which contains countless funeral monuments, some very beautiful. Those of the Chinese are generally shaped like a horseshoe; while those of the Annamites are shaped like slender pyramids or pretty small pagodas in miniature. Some more modest graves take the rough shape of a recumbent saddled horse. All of the small structures in this “city of the dead” are built from brick or clay and then covered with a thick layer of brown-coloured plaster which is made by infusing with water the viscous sap from a tree known to the natives as cay hiuoc. This plaster is easy to mould, and when dried it becomes as hard as brick and may easily be mistaken for stone. This substance is also used widely to coat the floors of local houses.

Besides these monuments, we sometimes chance upon corpses only partially covered with a little soil, or the edges of a coffin sticking up out of the ground. Perhaps the relatives fled during wartime before the burial had been completed.

The Plain of Tombs

This immense cemetery is very famous and it is deemed an honour to be buried here. The Plain of Tombs not only receives the dead of the immediate area, but also those of neighbouring provinces who, before dying, chose this as their last resting place. Many Annamites are convinced of the benefits of being buried here and there are even some who wish to die here too, in the place where they will later be buried.

Among the tombs roam flocks of vultures, unclean animals which nature seems to have created to rid the soil of rotting corpses and filth, and which perfectly fulfill the lofty mission of public hygiene and sanitation that was assigned to them.

This plain is traversed by two fairly busy roads; one part of it is now used as a parade ground by our Saigon garrison troops.

The plateau between Saigon, the arroyo de l’Avalanche and the Plain of Tombs is occupied by several villages. These include Yong-Guiton, at the intersection of boulevard Chasseloup-Laubat and the route de Tong-kéou; Phu-hoa, Han-hoa and Hiep-hoa, grouped near the Third Avalanche Bridge which connects them with the large village of Phu-Nhuan; Banian, located a few hundred metres from the citadel close to Saigon; and finally Tourane, a village established by Christians who, during the evacuation of the port of Tourane, followed the French to Saigon and were given land on which they built the village to which they gave the name of their place of origin.

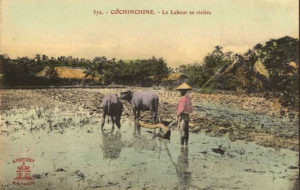

Riziculture near Saigon

The latter unfortunates have not ceased to be dedicated and helpful; they are energetic, clever, and provide many workers for the civic establishments of the city.

The other villages mentioned are inhabited largely by poor indigents from the interior, who, due to war, were forced to take refuge around us.

Near the village of Tourane is the French cemetery, another “Plain of Tombs,” where already too many of our brothers in arms are buried!

The plain north of Saigon is delightful. It is full of large trees which thankfully escaped the axes of our soldiers and now make possible a very nice promenade, especially in the early months of the year when flamboyants like erythrena charm our view with their “domes of fire.” During that period, the area around the Pagode Barbé (Barbé Pagoda) is magnificent.

Located at a crossroads near the citadel, the Pagode Barbé was formerly the Khai-Tuong (Aurore des presages) Pagoda, built by order of Minh Mang, son and successor of Gia-Long, on the site of the hut in which he was born during the war with the Tay-Son. It was near this pagoda that Captain Barbé was murdered, hence its current name.

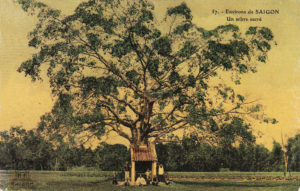

A sacred tree near Saigon

The greatest banian tree I have ever seen in Cochinchina is definitely that which stands next to the eponymous village of Banian, on the road leading to the village Binh-hoa which crosses the Second Avalanche Bridge. The base of this majestic tree is formed from several thick trunks welded together and surrounded by a network of roots comprising branches which fell vertically and became implanted in the ground. These trunks and roots now resemble elegant and slender columns and form cool and shady porticos into which one could easily retire to escape from the rays of the pitiless sun – if it were not for the numerous reptiles that have taken up residence there.

This beautiful tree is animated by flocks of green pigeons, which come to peck at berries, and which are shot ruthlessly by our hunters, who lie in wait under a neighbouring tamarind tree. Near this colossal representative of Cochinchina vegetation there are also a number of other banyan trees of different species, the leaves of which are eaten by the local people. These trees, now devoid of greenery, have a rather sad aspect.

Crossing the arroyo de l’Avalanche by the first bridge, we arrive in the village of Phu-My at the entrance to the Bien-Hoa road. Then, after heading along the left bank of the same arroyo, we emerge into a large, beautiful and fertile plain which is remarkably well cultivated – the plain of Go-Vap.

Gò Vấp

Nothing around Saigon is as lively as this corner of land; here we find workers who lie almost naked on the floor shelling peanuts, and, their costume aside, remind us of our farmers harvesting potatoes and other vegetables destined for the market. Here too, we may find growers of cotton and mulberry; Go-Vap silk is of very good quality and could become the source of a lucrative industry. Finally, we see everywhere men, women and even children bent under the weight of the foodstuffs that they are carry either to the market in Saigon or to that in the village of Go-Vap, one of the biggest markets in this rich country. One does not, however, visit the Go-Vap Market without a handkerchief under one’s nose, because of the smell of salted fish and nuoc mam which exudes from every stall.

Continuing our promenade, we encounter beautiful plantations of tobacco, objects of particular care on the part of the Annamites, who spend a large part of the day watering this plant. Each field has its own beam pump, similar to those encountered in our French villages of Champagne, Burgundy or Lorraine. These “nodding donkeys,” almost constantly in motion, give the plain great animation.

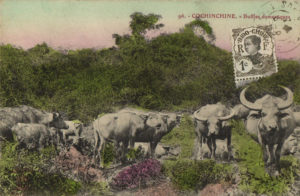

A herd of buffalo

Next to the plantation graze huge herds of buffalo whose broad heads are armed with long crescent-shaped horns. At the first sight of a European, these giants throw back their heads and snort angrily. They have been known to injur or even kill us with their horns. However, these animals are always very gentle with Annamites, and a child aged 12 to 15 years is sufficient to guard a herd.

At all points around the plain, one may hear the song of the grey blackbird, that friend of the farmer which follows him at a distance, feasting on the worms which he has just dug up. One may also hear the lark, that virtuoso of the air which seems to live almost entirely in the sky during the dry season, and whose song is of incomparable purity.

Pleasantly situated in the midst of a charming grove just a few kilometres from Saigon, we may find a very pretty temple which is a regular rendezvous for walkers. Built by order of Emperor Gia Long in honour of Monsignor Pigneau de Behaine, Bishop of Adran and Apostolic Vicar of Lower Cochinchina, this monument contains the mortal remains of this eminent man, who laid the first foundations of our domination over this country.

Pierre Joseph Georges Pigneau de Behaine (1741-1799)

The history of this prelate, whose evangelical virtues and apostolic zeal never diminished his patriotism, is not well known in France, so we cannot resist the desire to say a few words, pending the arrival of a more authorized biographer who can rescue such a beautiful life from oblivion.

Pierre Pigneau de Behaine was born in 1741 in a village near Laon. He arrived in Cochinchina in 1767 and was later named Bishop of Adran and Apostolic Vicar of Lower Cochinchina, a country whose destiny was to become French. The Bishop of Adran became the friend and close adviser of Gia-Long after the prince, driven out by the Tay-Son rebels, took refuge in the Gulf of Siam islands. He strongly advised his royal friend to seek the support of the court of Versailles, and offered to go to France himself to negotiate an offensive and defensive alliance between Louis XVI and Gia-Long. He left, in fact, accompanied by the Crown Prince, and signed on behalf of the Annamite monarch a treaty under which France was to send four frigates and 1,600 men to the assistance of the latter, who in turn would yield to France the island of Poulo-Condor and the port of Tourane, give the French complete freedom of traffic and permit them to found on the continent of Cochinchina all relevant institutions to facilitate their navigation and trade.

The Bishop of Adran then left France and travelled to India, where he awaited the promised assistance. But as we know, the ill-will of the comte de Conway, Governor of French territories in India, together with the events of 1789, prevented compliance with the treaty. The comte de Conway evaded Pigneau’s questions, and the prelate then learned from the court of Versailles the king’s decision that “the Cochinchina expedition would not take place.”

The Tomb of Pierre Pigneau de Behaine in 1867

This broken promise from the French government saddened, even humbled, the prelate, but it did not discourage him. Along with some French officers and a number of volunteer sailors engaged in India, he presented himself in Saigon, climbing a commercial building and casting terror among the troops of the Tay-Son by spreading the rumour that the soldiers that he had brought with him were only the vanguard of a huge army sent by the King of France to exterminate the rebels. The troops of Gia-Long, trained by French officers who had arrived with the prelate, took the offensive, penetrated as far as Hue and restored the royal authority.

After several brilliant successes, the Tay-Son were completely destroyed (1802). But the illustrious bishop, who had contributed so much to the reinstatement of Gia-long on the throne of his ancestors, could not see the culmination of his work. He died in 1799, surrounded by esteem and general admiration. The emperor, accompanied by the royal family, had gone to visit him during his illness, and after his death Gia-Long wept as one weeps for a father, along with his queen, his sisters and his concubines (the title of concubine not being a dishonorable one in Cochinchina), and organised a great funeral at which both Christians and idolaters flocked around the body of the emperor’s good friend and wise counsellor, whom they all called their “good father.”

The screen in front of the Pigneau de Behaine tomb

The funeral rites were all carried out according to royal protocol, and the body of the bishop was, according to his last will, buried in a garden that he owned outside Saigon. It was in this same garden, and over the tomb of the prelate, that Gia-Long commissioned the construction of the current pagoda. Here one may still find tablets exalting Pigneau’s merits, his talents and the services he rendered to the country, recalling the friendship which bound him to the emperor, and listing his titles, including the highest dignity after royalty, the title of teacher to the Crown Prince and the epithet “accomplished.”

In this way, the Bishop of Adran, helped by his countrymen, laid the groundwork for a French administration in the kingdom of Annam, which so marvelled our compatriots that they later carried out the conquest of Lower Cochinchina, founding there all our municipal hierarchy, from the mayor and councillors to prefects.

It is especially during the dry season, when the sky is illuminated every night, that one should visit this delightful last resting place of an illustrious son of France, returning to Saigon on a beautiful starlit evening through the mysterious Plain of Tombs.

A quayside scene in Chợ Lớn

Cholon, often referred to as Chinatown, was originally to have been incorporated into the boundaries of Saigon. But we have since had to modify the plan of a city that was believed to contain 500,000 inhabitants, and reduce it to more modest proportions. The city of Cholon having thus been separated, it now has its own municipality and administration. It is connected with Saigon via the high road along boulevard Chasseloup-Laubat and the low road alongside the arroyo Chinois.

Anyone who has not visited Cholon for a few years will be pleasantly surprised to discover, instead of a muddy city with narrow, fetid streets, a new city with mostly wide streets and pretty quays which has nonetheless preserved its oriental character. Many of the houses which now line the streets and quaysides have white walls and red roofs, and some have several storeys. All are brilliantly decorated with various designs in vibrant colours, which blend perfectly with the profusion of Chinese lanterns and banners, garlands and corporation signs, each inscribed in gold characters. While the city’s appearance owes much to the initiative and intelligent direction of our Inspector of Chinese Affairs, we must also pay tribute to the enormous sacrifices made by the city’s intelligent Chinese merchants, people of spirit and practicality, some of them millionaires many times over, who are not afraid to spend their own money in the cause of civic pride.

Shop houses in Chợ Lớn in the 1870s

Many of these merchants spontaneously proposed demolishing their old buildings in order to build nice new shop houses, and offered money to embellish the streets and waterfront areas in ways that now charm visitors.

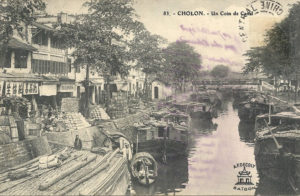

Nothing is more picturesque than the canal which runs through the Chinese city. It is constantly covered with boats, inhabited by whole families. Their boats are their only homes.

As noted above, despite its embellishments, Cholon retains its Chinese character, its eastern face, its local colour. It still contains a large number of pagodas, each with its idols, its hideous monsters and its many inscriptions, which I’m afraid that I can’t decipher. It’s curious to see the West, represented by our insouciant soldiers, laughing heartily in front of a big fat Buddha, who, sitting lazily, seems to symbolise the East. Almost all of Cholon’s pagodas are abandoned and have become homes to large colonies of bats, which are huge but perfectly harmless vampires, despite the ominous name they bear.

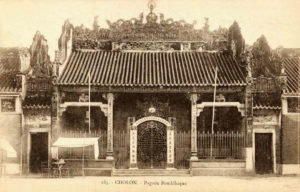

Among the monuments of Cholon, we must mention the Great Pagoda, a masterpiece of its kind, dedicated to the goddess of Kuang-chau Huay-quan, patron saint of sailors and travellers. It is filled with curious interior decorations, including a fresco ceiling, friezes and reliefs, gold inscriptions, paintings and a number of very original statues. The latter include a grotesque large gilt bronze Buddha, a gigantic goddess statue and many other smaller statuettes.

The Guangzhou Assembly Hall in Chợ Lớn

These should not be dismissed as mere festoons, rather we should consider them as objects which deserve to be studied, especially those on the outside, made from artistically-moulded clay, baked, painted and coloured, representing mountains, trees, flowers, butterflies, insects, birds, palaces, pagodas and bizarre characters in all poses, from those at rest to those in combat, either on foot or on horseback. There are also monsters dragons and other horrible and fantastic animals, such that even the liveliest European imagination could never dream of, and demons with hideous heads arranged in the most bizarre way. This curious specimen of Chinese architecture is worthy in every way of the attention of archaeologists and certainly deserves the honour of a special study by a competent researcher.

Seeing the many unfortunate beggars at the door of this monument, we regret very much the lack of a hospital. The Chinese who possess in the highest degree the spirit of association and civic pride, and who have been able to invent the pawnshops and the bank, have not yet been able to provide hospitals here. Perhaps this type of institution stems from an eminently Christian virtue of charity. We are currently involved in the construction of a hospital in Cholon.

The Chợ Lớn creek which ran through the centre of the town

One thing that we must not fail to mention among the relevant sights of the Chinese city are the famous Puits de l’éveque d’Adran (Bishop of Adran Pumps), a water well located in the middle of the arroyo whose excellent water is transported by boats throughout the southwest part of the province of Saigon, and sometimes even as far as My-Tho. This well takes the form of an island, a mound of earth covered with greenery, which is constantly surrounded by boats collecting water to quench the thirsts of those who inhabit the low and marshy plains.

Cholon has about 40,000 inhabitants, among whom there is not at present a single Catholic. Almost all are traders or workers; but it is the Chinese who hold the trading monopoly, not only in Saigon, but throughout all of Cochinchina. They aim to compete even with the Europeans, and it is for this purpose that several Chinese merchants have already ordered small steam ships from France.

These traders not only concern themselves with matters concerning their small town, but also take on board, with surprising ease and rare intelligence, our ideas and our civilisation. They are very attached to the destinies and interests of our young colony, which can count on their professionalism and dedication, since its future is also theirs.

Boats on the arroyo Chinois

The establishment of the Chinese colony here does not only date from our conquest of Cochinchina; it may be traced back to the late 17th century. At that time, some Chinese remained loyal to the Ming dynasty, and wanting to escape the domination of the Qing, were authorised by the King of Annam to go and settle in the province of Gia-Dinh (Saigon), then newly conquered from the Cambodians. They chose the island of Cu-Lao-Pho, near Bien-Hoa. This island quickly prospered in their hands, and soon the new colony was providing woven and dyed silk and cotton to the Annamites of this region, who at that time were unfamiliar with the arts of cultivating mulberry and cotton trees, weaving and dyeing.

The revolt of the Tay-Son came to disturb this prosperity, and the settlers were forced to withdraw to the territory of Saigon, where they founded the city of Cholon. Thereafter its commercial importance increased day by day under the direction of its skilful founders, who soon invited more of their countrymen to join them. Some of these settlers were periodically replaced by others, but large numbers lived in the city for a long time and intermarried with the Annamites, without thinking of returning to China. That is why Cholon has so many Chinese-Annamite mixed-race people, known as Minh Huong. However, if death surprised them away from their homeland, almost all would still have their mortal remains transported back to their ancestral land, in order not to be deprived of the proper worship made by the living to the dead.

The Chinese have imported to Cochinchina their morals and religion, so it is not absolutely necessary to go to China to study the inhabitants of the Middle Kingdom.

The Pagode des Clochetons, Chợ Lớn, in 1861

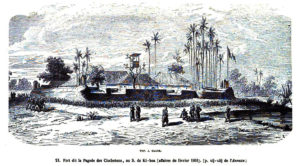

Near Cholon, one may also visit the Pagode des Clochetons and the small fort of Cay-Mai, two names cited in relation to the Battle of Ky-Hoa.

Fort Cay-Mai is named after a tree which gave flowers with a pleasant scent reminiscent of the smell of violet. Before we arrived in this country, it is said that young girls and young boys (especially students) would gather under its shade to make offerings to the Buddha, sing love songs and strew the ground with flower lotus and water lily.

We will stop here, because to say any more would necessitate describing all of our colony, the whole of our Asiatic France, which we must postpone until another time.

P C Richard, Artillery lieutenant of the navy and the colonies

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.