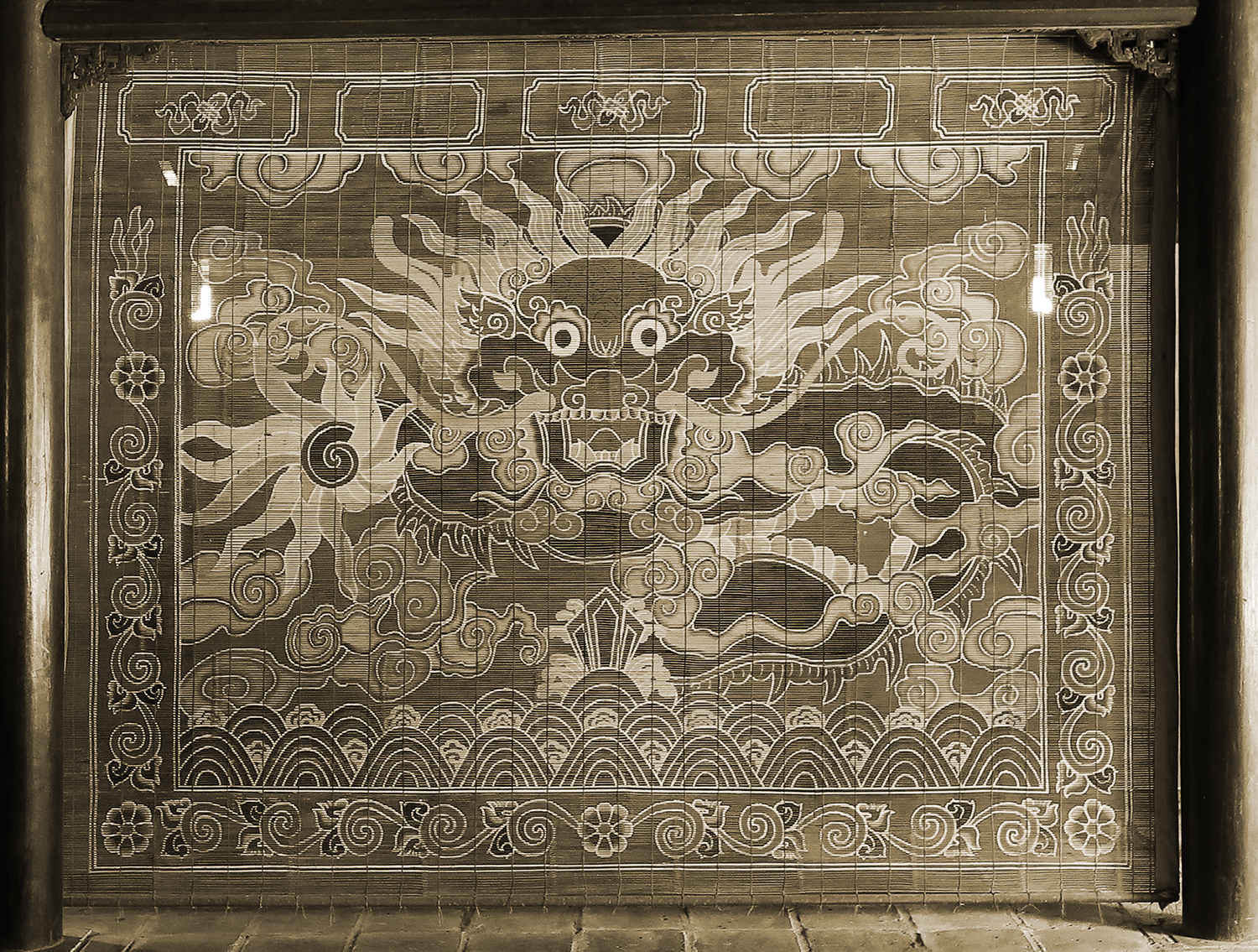

A royal screen in the Citadel

A fascinating recollection of the court of Emperor Đồng Khánh (1885-1889), written by Frédéric Baille, who served as Acting Resident Superior of Annam from 28 November 1894-26 April 1895.

The courts of Annam were, until the last days of the reign of Thu-Duc, relentlessly closed to profane eyes.

Emperor Đồng Khánh (1885-1889), BAVH 3, 1941

They were always enveloped by an immense mystery, which has served as an accomplice to many crimes. Even today, despite the large and perhaps rather hasty concessions made to European curiosity, it is impossible, apart from in the performance of official duties, to enter the royal palaces, and in particular the building where the king’s mother lives.

The mother of Dong-Khanh has always lived a cloistered life, hidden from the view of all except those of her immediate retinue, as befitting a woman of her rank. No European is permitted to contemplate her features. It seems that this lady and her life are surrounded by a mystery even more impenetrable than that of the other princess who bears the title of Queen Mother, the mother of Thu-Duc. We were given a glimpse of her during the passage of M. Vial, Résident-Général, who had solicited the honour to present to her his respects.

That spectacle was, moreover, one of the more curious to have remained in our minds. After travelling for more than 20 minutes through an inextricable maze of gardens and corridors, we were brought into a fairly large courtyard, surrounded by high walls. Two orchestras of women musicians, arranged in parallel lines, filled the air with their strange sounds. We owe it to the truth to add that the age and physique of almost all these artists commanded respect, and that even they would have left even the most outgoing stranger frozen in awe. After several minutes of waiting, we were finally admitted to a relatively low room.

The main hall of the Diên Thọ Palace, official residence of the Queen Mother

At the back of this room, we saw a blind made of thin bamboo strips and decorated with multicolored dragons. In front of it, wearing full dress, knelt the king, his hands folded in the attitude of prayer which among the Annamites denotes respect. Behind this blind, hidden from profane eyes in the twilight of a sanctuary, stood the old Queen Mother. First the king, and then the Europeans, did their homage to her. Then, from behind the blind, we heard a voice, or rather a barely noticeable whisper, in response to our display. Suddenly the thin bamboo blind rose slowly, like a theatre curtain.

There stood the motionless idol, dressed in dress of royal yellow, with a fixed stare, her yellow-white complexion resembling the ivory of an old crucifix. It was only a vision, nothing more. The blind fell almost immediately, with a quick movement. New compliments were exchanged, and the king, once more at great length, knelt before the blind to make his lais of farewell.

Such was the short ceremonial of this interview, a supreme concession made by royal majesty to the new order of things, and to satisfy our sacrilegious curiosity.

An external view of the “Second Queen Mother’s Palace,” aka the Trường Sanh Palace, in 1928 (Fonds Sallet)

Every day, the king is assisted by a staff of women taken from all hierarchical classes of the women’s quarters. Thirty of them stand guard around his private apartments.

Five women are always near his person, taking turns, alternately, to provide for his personal care and grooming. It is they who dress him, maintain and clip his long nails which denote his scholarly standing and are at least as long as his fingers, perfume him, wrap his head coquettishly with a delicate and silky scarf of yellow crepe, and finally ensure even the smallest details of his costume.

These are the women who also serve him at his table.

His Majesty usually takes three meals a day; at six and eleven in the morning and at five in the evening.

Each meal consists of 50 different dishes prepared by thuang-tieng, who, numbering 50, accomplish the service of the royal kitchen. Each of them therefore prepares one dish, and when the bell sounds, passes them to the thi-viés (chamberlains), who convey them to the eunuchs.

The courtyard of the Càn Thành Palace, where the emperor ate and slept, in 1925 (Fonds Sallet)

These, in turn, transmit them to the king’s most senior women servants, and it is only they who will have the honour of offering them, kneeling, at the royal table. His Majesty barely touches some of these dishes and drinks some kind of special eau-de-vie made with lily seeds and perfumed with aromatic plants. That was at least the old etiquette. Dong-Khanh drinks wine from Bordeaux, which doctors have prescribed to repair the disorders of his fairly poor health.

The rice eaten by the king, which forms the basis of his nourishment when he is alone and not forced to eat European food, must be very white and specially selected, grain by grain. It is cooked in a clay pot which is broken after every meal. The quality of the chopsticks which his Majesty uses to eat is also important. Ivory chopsticks seem too heavy for the royal hand, so the ones used by the king must be made from bamboo which has just come into leaf, “and renewed every day.”

The amount of rice eaten by the king is carefully determined, and the agreed is never exceeded. If he does not eat this amount, if he feels less hungry, he immediately calls his doctors and demands remedies, which he will only absorb after they have been tasted beforehand.

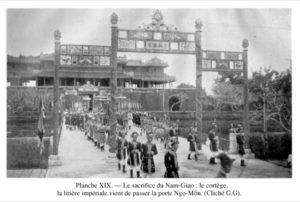

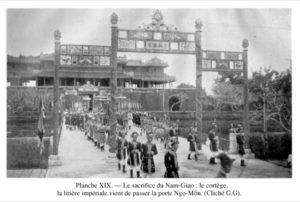

The royal cortege leaves the Citadel for the Nam Giao Esplanade, BAVH 1, 1936

Each province of the kingdom sends to the court, for the royal food, the best productions of the soil, part of which comes from taxes paid in kind. For example, Cochinchina formerly sent rice from Ba-Thac, fish caught in the big lake (Kho-ha), dried shrimp, mangosteens, palm grubs (big grubs found in the heads of date palms and coconut trees), young caimans and lychees.

In the second month of each year, after three days’ abstinence, the king goes with great ceremony, escorted by the whole court, to celebrate the feast of Nam-Giao, that is to say to offer sacrifice to heaven. The ceremony, the most solemn of all year, takes place near a fan-shaped high hill covered with pine, which, according to Annamite legend, serves as a screen and defence for the citadel.

On that day, the sovereign, usually almost invisible to his people, is shown to all, carried in the ngoe-lo, a sort of covered chair with glazed windows, from which he can see and be seen. Tents are pitched in advance within the walls of the Esplanade des sacrifices so that he can spend the night there with his court. Right in the centre is a masonry platform which is accessed by high stairs. It’s there that the altar, decorated with yellow and red fabrics borrowed from the palace, is prepared. This is also where the sacrifice takes place. At midnight, the military mandarins immolate a buffalo, and the king offers it in great pomp to heaven, which he salutes with five consecutive lais while a mandarin reads aloud the prayers prescribed by the rites, at the same time burning numerous pieces of silk. The feast is usually ended by dawn, and His Majesty then returns to the Citadel.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group page Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.