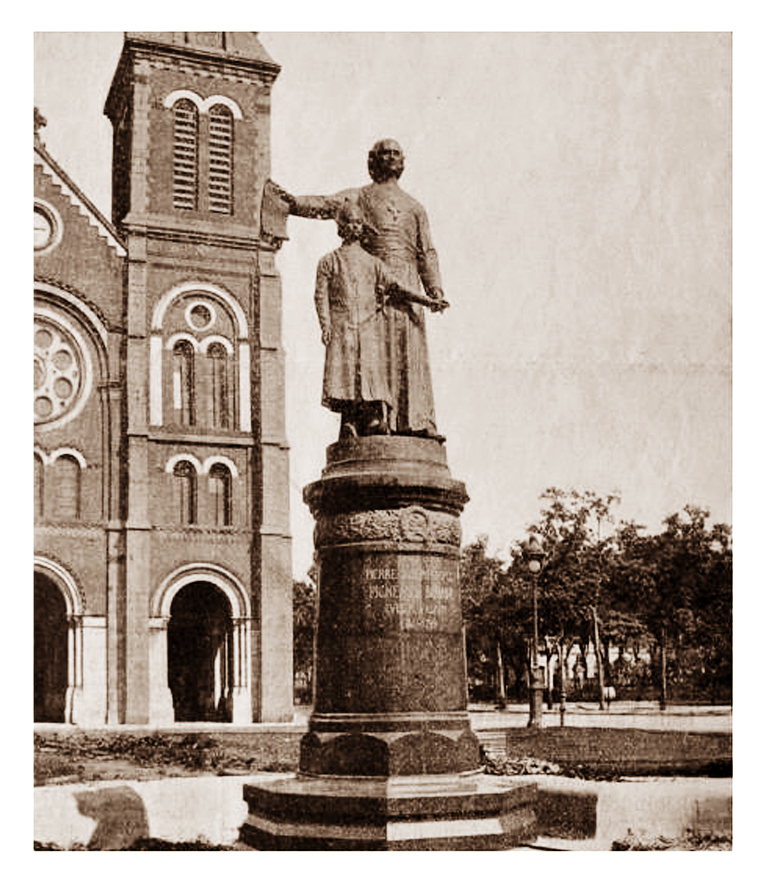

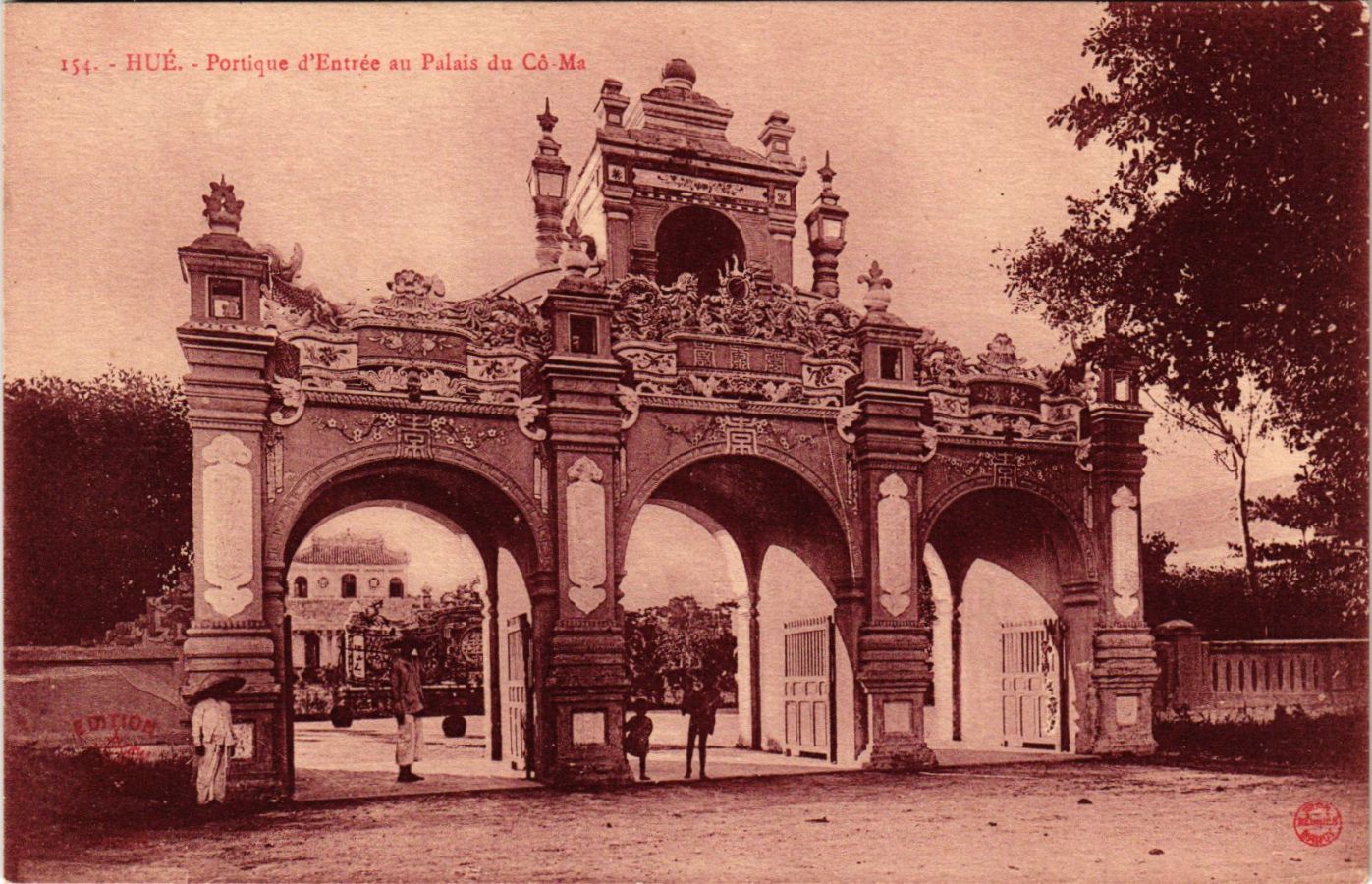

The main gate of the Viện cơ mật or “Secret Institute,” which functioned as the Privy Council and key mandarin agency of the royal court

Those interested in the development of our colonial policy in Indochina will have read with real appreciation about the significant reforms which have been promulgated in recent days by Emperor Bao-Dai.

Less than a year, in fact, has elapsed since the return of the young prince from France. We still remember the cordial words of farewell addressed to him before he boarded his ship in Marseille by the Colonial Secretary, M. Albert Sarraut, promising all the support of the French government to the sovereign called to deal with a situation which his long absence had made difficult. For what was already being called in Indochina the “Bao-Dai experiment” posed a number of questions.

Emperor Bảo Đại pictured in 1935 (Fonds Sogny-Marien)

How could the actions of a monarch whose reason now seemed so perfectly formed to Western conceptions be accommodated to that of certain circles of “old Annam,” with their strong attachments to the political and moral traditions of Confucianism?

We know now how events have taken shape so far. Welcomed by eager people in Tourane and Hue, and then through all the provinces of the kingdom, the young emperor has quickly gained sympathy and confidence through a series of happy gestures, abandoning obsolete protocol and demonstrating his desire to live in close contact with the Annamite people.

Moreover, by his regnal ordinance of 12 September, he announced his intention to undertake many reforms in the administrative, judicial and educational fields. Soon after, finally, he called to the leadership of his own cabinet, with the rank and prerogatives of a minister, an entirely new personality from Tonkin, M. Pham-Quynh, whose influence amongst young intellectuals has always been considerable.

Against this background, around two months ago, the Nam-Giao Festival was held. The accomplishment of the rites of this ceremony was to Bao-Dai a new and definitive consecration of the imperial power with which he was now fully clothed in the eyes of his subjects.

Phạm Quỳnh (1892-1945)

The time of the reforms approached. By an order of 3 May last, in full agreement with Governor General Pasquier, the young ruler of Annam came to initiate them. Whatever his good intentions, Bao-Dai was not slow to realise that his initiatives could, to some extent, be paralysed by the “atmosphere” of the court of Hue. For, undoubtedly, a gulf already begun to appear between the desires of the sovereign and those of his respectable mandarins, all of whom had been in his entourage for a good many years. These were people for whom policy was always blended perhaps a little too much with the games of small intrigue so often forged in the ancient courts of the Far East. No-one would doubt that a figure like H E Nguyen-Huu-Bai, a scholar of senior years and Prime Minister of the Court of Annam for the past quarter century, remains worthy of the highest honours. Yet is it desirable that in future the gatekeepers between the emperor and his people should continue to be tied by invisible bonds to the forms and traditions of a bygone era?

Absolutely not, declared the wish of the Emperor, which on this occasion was consistent with that of the administration of the protectorate.

In fact, it was less a problem for Bao-Dai to address the final implementation of the reforms promised by last September’s regnal order than to tackle the issue of the “atmosphere” in which these reforms could and should be realised.

Emperor Bảo Đại’s new ministers, from left to right: Hồ Đắc Khải, Phạm Quỳnh, Thái Văn Toản, Ngô Đình Diệm (later RVN President), Bùi Bằng Đoàn

Basically, it was a question of ensuring the quality of his entourage – finding men who were ready to co-operate loyally with the emperor, to bring him the support of their enlightened wills. After all, how could the sovereign initiate reforms if he were unsure whether his closest collaborators would apply them with the loyalty and perseverance necessary, in a period of transition, for their efficiency?

So here, briefly summarised, is what was eventually determined by Bao-Dai immediately after the Nam-Giao Festival. The resignations of the six ministers already in office were accepted by the sovereign, who then took responsibility for changing the composition of the government. With the exception of H E Thai-Van-Toan, who was moved from Finance to Public Works (with the addition of Rites and Fine Arts), the Cabinet today consists of four entirely or mostly new personalities – Pham-Quynh (who also occupies the post of Director of the Emperor’s Cabinet) in charge of Education, Ngo-Dinh-Diem in charge of the Interior, Bui-Bang-Doan in charge of Justice and Ho-Dac-Kai in charge of Finance – with the former Minister of War having not been replaced. An important indication is that all these new ministers, who between them have an average age of just forty years, have only been invested for a period of three years, the Emperor having also taken care to clarify in his ordinance that he had chosen them only by consideration “of their personal value, of their intellectual and moral qualities, and of the good reputation they enjoy in the eyes of the people, regardless of their seniority or rank in the mandarin hierarchy.”

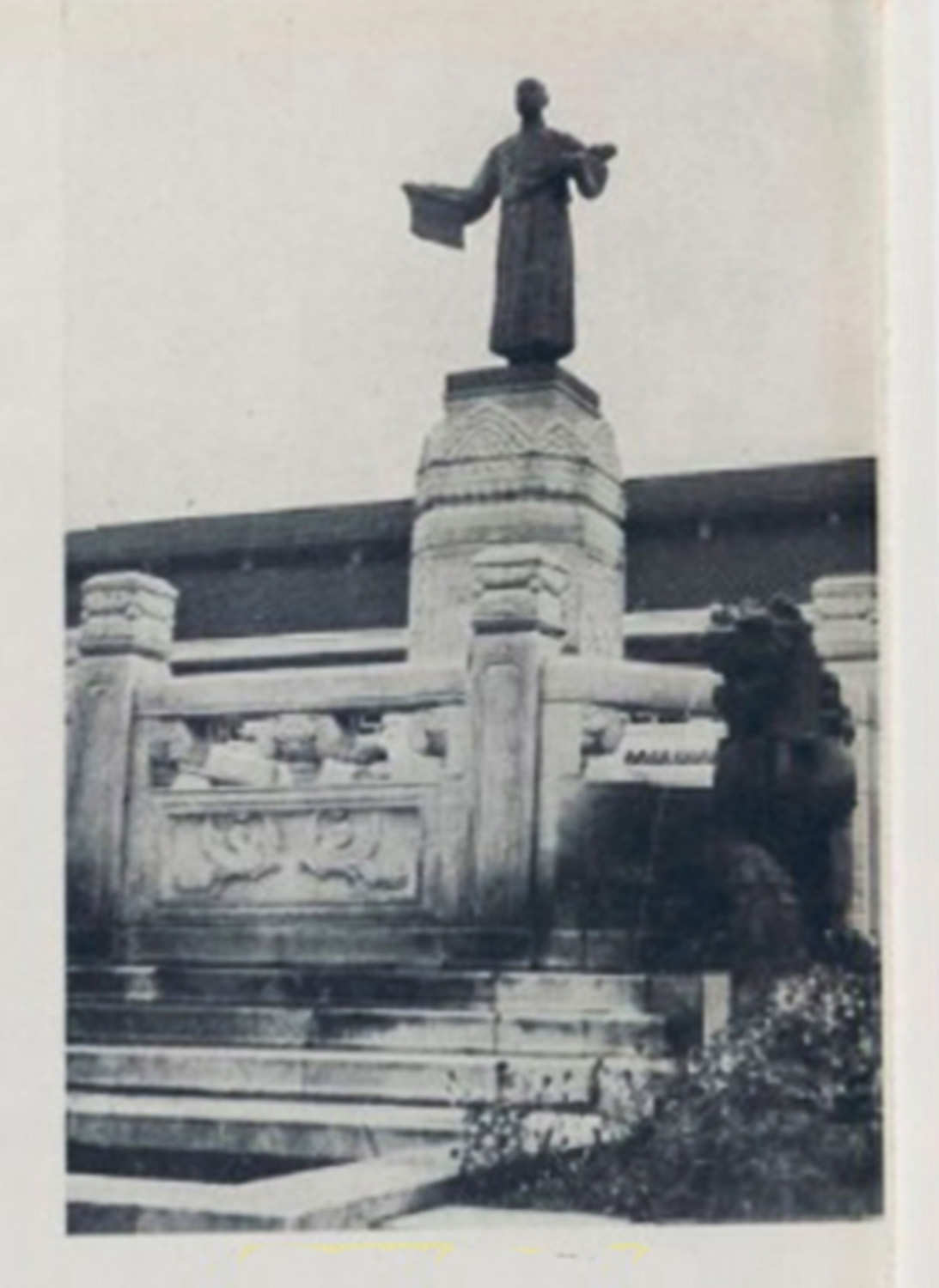

The original main building of the Viện cơ mật or “Secret Institute,” which functioned as the Privy Council and key mandarin agency of the royal court

Of course, in Annam, and even in the whole of Indochina, these decisions by Bao-Dai were not without a considerable impact: we must go very far back to find any trace in the political actions of an Annamite sovereign of such radical changes to the state of affairs in the kingdom. Of particular note is the fact that the emperor also announced his will always to chair personally the meeting of the Council of Ministers, or Co-mat, “taking himself the direction of the country’s affairs,” that is to say actually governing, in contrast to his predecessors, slaves to the rites and traditions of the court, who were content not to.

If the consequences for Annam of the new order established in Hue have already appeared, it is not superfluous to attempt now to take a look at the future: for, to have been approved by Governor-General Pasquier, Bao-Dai’s decisions must interest the protectorate in a special way.

In this respect, it seems that our representatives in Indochina have nothing to fear from this small “palace revolution,” to call it by its name, which the emperor has just completed with such flexibility. Not that the Resident-Superior in Annam has always met systematic opposition to his wishes at the court of Hue. Although in the early years of the protectorate, obstruction was common, it has over time become more and more rare. However, the archaic organisation of the court, the multitude of client relationships connected to the various personalities, and the games of intrigue, still created frequent difficulties. Happily, the road to the royal residence Kien Trung Palace is now more level than it was before.

Emperor Bảo Đại pictured in 1932 (press image)

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group page Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.