Saigon – Les Messageries maritimes – Le Courrier de France

Saigon’s port has played a crucial role in the city’s development as an economic powerhouse. This overview traces its history, from the late 17th century to the present day.

The earliest port facilities in Saigon were established before the arrival of the Việts, at a time when the city was still an outpost of the Cambodian mandala known as Prey Nokor.

A marriage alliance in the early 1620s between a daughter of the second Lord Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên of Đàng Trong and King Chey Chetta II of Cambodia was followed by the first Việt settlement and the establishment of a Nguyễn customs house in this port, which suggests that at the time Prey Nokor was already attracting a regular throughput of merchant traders.

A marriage alliance in the early 1620s between a daughter of the second Lord Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên of Đàng Trong and King Chey Chetta II of Cambodia was followed by the first Việt settlement and the establishment of a Nguyễn customs house in this port, which suggests that at the time Prey Nokor was already attracting a regular throughput of merchant traders.

However, it’s probable that the Mercantile port did not develop significantly until the late 17th century, when supporters of the overthrown Ming dynasty settled in Gia Định prefecture and took control of the shipping and processing of rice from the Mekong Delta. This early mercantile port was located on both sides of the Bến Nghé creek, at its junction with the Saigon River.

Just to the north of the mercantile port, in the area in front of today’s Majestic Hotel, was the Royal wharf, which Pétrus Trương Vĩnh Ký (Souvenirs historiques sur Saïgon et ses environs, 1885) tells us was originally known in Khmer as Kompong Luong, suggesting that it may have originated as a royal landing stage built by the Cambodian uparaj (vice kings) who resided in Prey Nokor down to the end of the 17th century. Later, it became known by the Vietnamese name Bến Ngự and was used by the Nguyễn rulers and their mandarins when disembarking from their ships to visit the Dinh Phiên Trấn (1698) and later the two Gia Định Citadels (1790, 1837). Pétrus Ký adds that in the pre-French era, this wharf was equipped with a royal bath house known as the Thủy các or Lữ Ông Tạ, built on floating bamboo rafts!

Soon after his forces recaptured Gia Định from the Tây Sơn in 1788, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh founded a Naval workshop just to the north of the royal wharf, in the area between modern Mê Linh square and the Thị Nghè creek. It was here, with the assistance of French engineers, that a fleet of modern warships was assembled, tipping the military balance in Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s favour throughout the remaining years of the Tây Sơn War. After Nguyễn Phúc Ánh ascended the throne in 1802 as Emperor Gia Long, this naval workshop was expanded into a large shipbuilding facility and cannon foundry, which at its height employed several thousand workers of various professions.

Soon after his forces recaptured Gia Định from the Tây Sơn in 1788, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh founded a Naval workshop just to the north of the royal wharf, in the area between modern Mê Linh square and the Thị Nghè creek. It was here, with the assistance of French engineers, that a fleet of modern warships was assembled, tipping the military balance in Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s favour throughout the remaining years of the Tây Sơn War. After Nguyễn Phúc Ánh ascended the throne in 1802 as Emperor Gia Long, this naval workshop was expanded into a large shipbuilding facility and cannon foundry, which at its height employed several thousand workers of various professions.

Following the arrival of the French, Saigon’s location 83km or 45 nautical miles from the sea – an accident of history resulting from its excellent harbour, closeness to the rice mills of Chợ Lớn and long-established customs and excise infrastructure – was believed by many colonial commentators to be one of the key factors preventing its port from competing effectively with Hong Kong, Singapore and even Jakarta. In the 1860s and again in the 1880s, colonial officials debated at length whether the Cochinchina capital and its principal seaport should be relocated to Cap Saint-Jacques (now Vũng Tàu) with a view to realising its full potential, but on each occasion this idea came to nothing and both capital and seaport remained where they were.

The French opened the port of Saigon to navigation and commerce on 22 February 1860.

Cochinchine – Saigon – Les sampans des passeurs, près de la pointe des blageurs

In February 1861, the Compagnie des Messageries Impériales (known after 1871 as the Compagnies des Messageries maritimes) was entrusted with postal and passenger services from Marseille to Saigon, and part of the existing mercantile port in Khánh Hội (now District 4), the Messageries maritimes wharf or Dragon house wharf (Bến Nhà Rồng), became its headquarters. Thereafter, the company’s courrier vessels conveyed mail and passengers from Marseilles via Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to Saigon and then onward to Hong Kong, Shanghai and Yokohama, with connecting services from Saigon to Manila. These courrier vessels were operated initially on a monthly basis, but their frequency increased to once per week following the opening of the Suez canal in 1869. The Compagnie des Messageries maritimes enjoyed a monopoly until 1901, when the Compagnie de Navigation des Chargeurs Réunis was permitted to launch rival services and share the Messageries maritimes terminal.

During the early years of colonial rule, the Mercantile port (Port de commerce) continued to use wharves in the area immediately north of the arroyo Chinois (Bến Nghé creek) extending as far as the Rond-point (modern Mê Linh square). In subsequent years, this quayside area was known variously as quai de Donnaï, quai Napoléon, quai du Commerce, quai Francis-Garnier and latterly quai le-Myre-de-Vilers. However, in 1881 these wharves – known to the French as the “appontements de Canton” and “appontements de Charner” – were entrusted were transferred to the control of the river courriers (see below), so replacement mercantile port facilities had to be provided in Khánh Hội (modern District 4). By the mid 1880s, these new mercantile port facilities extended nearly 1km southeast along the riverbank beyond the Messageries maritimes compound.

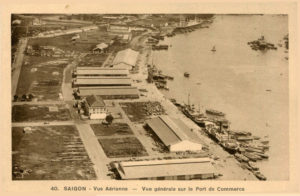

Saigon – Vue générale sur le Port de commerce, 1930s

Further expansion of the Port de commerce took place in the period 1900-1912. In 1903, the Société de constructions de Levallois-Perret built a Swing Bridge (Pont tournant) across the arroyo Chinois to connect the port with the city. This carried not only a road, but also a rail freight spur which connected the Saigon-Mỹ Tho railway line on rue Krantz/rue Duperré (modern Hàm Nghi) with both the Messageries maritimes wharf and mercantile port. Then in 1906, the canal de Dérivation (now the Tẻ Canal which separates District 4 from District 7) opened to shipping, providing merchant shipping with an alternative to the overloaded arroyo Chinois. By 1912, additional wharves, warehouses and loading equipment had been installed, extending the Port de commerce as far as its mouth.

The final phase of expansion came in 1925-1929, following the relocation of Xóm Chiếu Parish Church from its former compound on rue Jean-Eudel (modern Nguyễn Tất Thành) to its current site. At this time, the mercantile port was increased further in size and equipped with new wharves, cranes, and administrative buildings, a Decauville narrow gauge railway network and a set of nine iconic hangar buildings, all built by the Société Levallois-Perret.

In 1881, as noted above, all of the wharves between the arroyo Chinois and the Rond-point (including the former royal wharf) were transformed into the River port (Port fluvial) and entrusted to the management of the Compagnies des Messageries fluviales, which subsequently ran postal and passenger services to Phnom Penh and later to other destinations in French Indochina, as well as along the coast to Bangkok. Sadly, this company’s grand former headquarters, the Halles des Messageries fluviales, built in 1889 by the Maison Eiffel, was remodelled beyond recognition in the early 2000s by its current occupant, the Riverside Hotel at 18-20 Tôn Đức Thắng.

Saigon – Le “Donaï” des Messageries fluviales à l’appontement

From the early 1860s, the Messageries maritime wharf, Mercantile port and River port all came under the control of a French Commercial Port Directorate (Direction du port de commerce). In 1879-1880, a grand new colonial headquarters building was constructed for this department on the headland near the Signal Mast. Rebuilt again in 1918, the Commercial Port Directorate building survived until 2007, when it was demolished to make way for the Saigon One tower.

After the arrival of the French, the quayside immediately to the north of the River port, between the Rond-Point (known after 1878 as the place Rigault de Genouilly) and the arroyo de l’Avalanche (Thị Nghè creek), became the Naval port (Port de la marine), under the control of the French Navy (Marine nationale française).

The southernmost section of this naval port, extending nearly 600m north along the river from the Rond-Pont and known initially as quai Primauguet and later as quai de l’Argonne, housed the Naval Commander’s headquarters (Hôtel du Commandant de la Marine), the Naval Artillery (Artillerie de Marine) and the Naval Barracks (Caserne de la Marine, later Caserne Francis-Garnier). This area was initially intersected by the cross-town “Junction canal” and several smaller waterways, but by the late 1860s these had all been filled to make way for further expansion.

The Arsenal de Saigon (Ba Son Shipyard) in the late 18th century

Beyond that, in the 22-hectare compound previously occupied by the former royal naval workshop which bordered the mouth of the arroyo de l’Avalanche (Thị Nghè creek), the French established their Naval Arsenal and Shipyard. Founded in 1864, it was gradually equipped with state-of-the-art repair workshops, and by 1888 it boasted several boat repair docks, including a dry dock of 168m which “could receive the largest ships of war, ensuring our squadrons a perfectly safe and convenient refuelling and rehabilitation point.” (Eugène Bonhoure, Indo-Chine, 1900). After the reorganisation of the French navy in 1902, the Naval Arsenal became the headquarters of the “Naval Forces of the Oriental Seas” under the control of a Vice Admiral, comprising 38 vessels, 183 officers and 3,630 troops. Thanks to further upgrades in the early 20th century, by 1918 the Naval Arsenal could not only maintain and repair the French fleet, but also build new vessels of up to 3,500 tonnes in weight.

After 1956, the former Messageries maritimes, River and Mercantile ports were taken over by the Saigon Port Authority (Thương Cảng Sài Gòn). In 1966-1967, the US Navy built additional military cargo facilities at Newport (Tân Cảng), Camp Davies (Tân Thuận), Cát Lái and Vũng Tàu and a large combat/logistics base and fuel storage facility in Nhà Bè. In 1973, following the Paris Peace Accords, these military installations were taken over by the Saigon Port Authority, which in the following year launched a joint project funded by Taiwan to establish a 65-hectare Export Processing Zone (EPZ) in Tân Thuận (modern District 7), southeast of Khánh Hội merchant port. However, due to the fall of Saigon in April 1975, this project was never implemented. The existing mercantile ports have since continued to be administered by the Saigon Port Authority.

Container ship at Cái Mép-Thị Vải Deepwater Port (image by TCIT)

In 2005, due to lack of expansion capacity and increasing river and road congestion around the city-centre port facilities, the government decided gradually to relocate the existing ports at Tân Cảng, Khánh Hội, Tân Thuận downriver. Since then, larger dedicated port facilities have been developed at Cát Lái (District 2), Hiệp Phước (Nhà Bè) and Cái Mép-Thị Vải (Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu). The opening of the latter in 2009 finally realised the fleeting French idea of building a major port in Cap Saint-Jacques, and by 2016 that installation was handling over 62 million tonnes of freight and container cargo. While some small and medium-sized cruise ships may still navigate upstream to Khánh Hội, larger passenger vessels are now obliged to dock at Phú Mỹ (Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu), some 2.5 hours by road from Saigon. At the time of writing, the Nhà Rồng-Khánh Hội port area is earmarked for redevelopment as an up-market residential area.

After the departure of the French, the Naval port was managed first by the RVN and latterly by the DRV Ministries of National Defence. The colonial naval barracks and artillery buildings in the riverside area north of Mê Linh square (initially Bạch Đằng, now Tôn Dức Thắng street) continued to house naval personnel right down to the 1990s, but since that time the old artillery compound has been vacated by the military and completely redeveloped with new hotels and office blocks. Today, the only surviving operational naval installation in this area is the old Caserne Francis Garnier barracks at 1A Tôn Đức Thắng.

In 1955, the Arsenal was renamed Ba Son Shipyard (a name derived from the French bassin de radoub) and subsequently functioned both as naval shipyard and commercial enterprise, building vessels of up to 10,000 deadweight tonnage (DWT) and repairing vessels of up to 35,000 DWT for both foreign and Vietnamese ship owners.

Ba Son Shipyard pictured before its destruction (Alexandre Garel)

However, in 2005 it was also decided to relocate all ship repair and construction from Ba Son to Cái Mép-Thị Vải and other down-river facilities, leading in 2015 to the decommissioning of Ba Son. Despite the fact that the Ba Son compound incorporated many excellent examples of French industrial architecture dating back to the 1880s, the complex as a whole was never recognised as a heritage site. In recent years, several Vietnamese heritage specialists argued publicly that “the cultural and historical relics of Ba Son Shipyard, large dry dock and related works should be listed as national heritage site,” while travel and tourism practitioners voiced the hope that the old Ba Son buildings might one day be transformed into a world-class maritime heritage and leisure complex. Instead, a decision was taken in 2015 to sell the 25-hectare compound to a developer, which proceeded to demolish its surviving heritage buildings to make way for another “deluxe residential zone.”

Tim Doling

Saigon – The Compagnie des messageries maritimes

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now and Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.