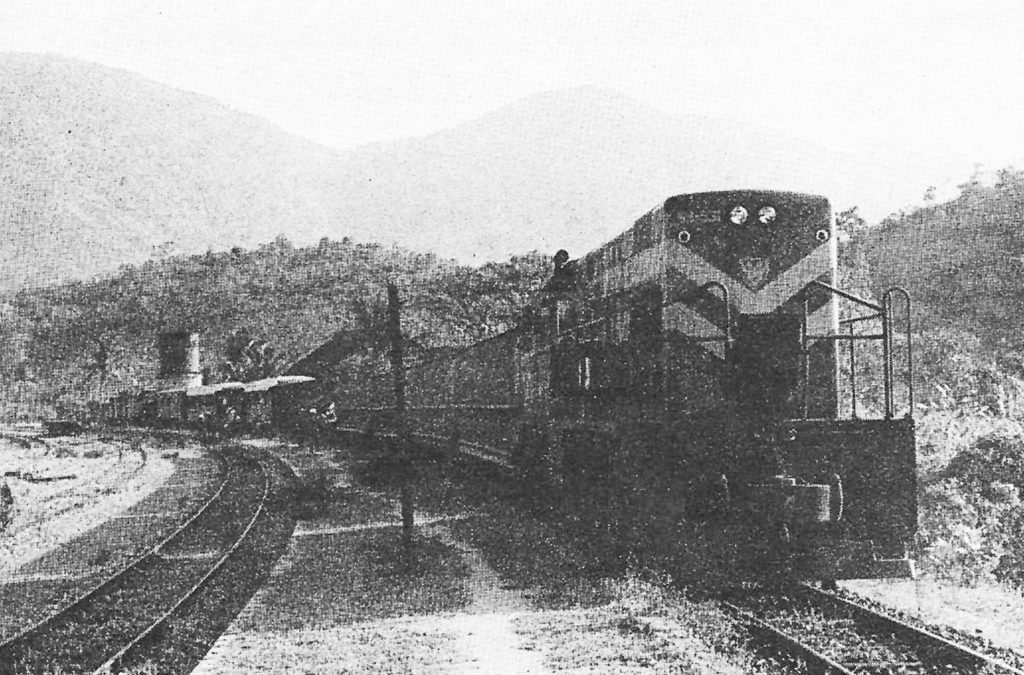

GE U8 BB-936 at Cape Varella (photo by Paul S Stephanus)

Every Việt Cộng attack on it is an indirect compliment to the line.

For four years after the end of the French war in 1954, the transportation system of Việt Nam below the 17th Parallel lay in ruins under the rubble of the two wars which had swept over it. Both the railway and the road system were fragmented by blown bridges and torn-up track and pavement. In the comparable period in Europe (1946-1950), transportation and the local economies recovered almost entirely from even more complete destruction, with proportionately less American aid than Việt Nam had available; but Việt Nam marked time. The reasons for this go deep into the roots of the present conflict, and several more years must pass before the emotional and political dynamite surrounding Việt and American policy in that era is disarmed so that a cool appraisal is possible.

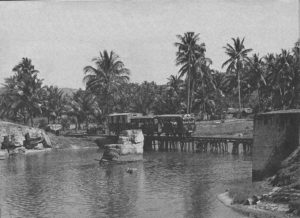

Makeshift operations have characterised many section of the railroad through recent wars. South of Quảng Ngãi, a gas-powered section speeder passes over a fragile trestle alongside the cribs of a bridge that was bombed out in World War II. (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

While a political climate as complex as 16th century Italy raged overhead, the railway, like a French bureau which grinds on through the rise and fall of parties and governments, held itself together. In Việt Nam, it is the policy to maintain a fixed workforce regardless of traffic, and since 1954 this has more than once kept the railway organisation from falling apart. [This policy has been slightly modified recently. The work force has been allowed to decline, mainly by attrition, from 6,000 in 1960 to 3,400 at present. Five hundred and thirty of these railroaders were drafted, including a hard-to-replace engineering staff.] Furthermore, in Việt Nam, technicians such as the railway officialdom are basically nonpolitical, and the railway board is not a power base as it might be in Europe. This, too, has spared the railway some problems.

In April 1958, American aid finally reached the transportation system (in contrast to the situation in Europe after World War II, when rail and highway rebuilding was in the first-months priorities of United Nations Relief & Rehabilitation Administration aid), and in 18 months it restored virtually all the damage.

In April 1958, when the reconstruction program began, the system was more or less normal south of Ninh Hòa, but from there north, only fragments were “operational,” and then only in the sense that light local passenger service was furnished by gasoline speeder trains, Việt Minh style, over flimsy wooden trestles and shooflies. Repairs began with house-to-house inquiries by the police or railway personnel to find out where the Việt Minh had buried rails and ties. Since the Việt Cộng insurrection was already overt (the first acts of terrorism and destruction took place in 1957), and was especially strong in the northern provinces of South Việt Nam, it was sometimes worth a man’s life to reveal a cache of buried railroad equipment. However, one by one, the hiding places came to light and the track restoration began. Ninety-eight bridges were repaired or replaced. In many cases, it was possible to lift the bridges intact from the water where the Việt Minh had flung them. Many of the bridges were a standard 50-meter truss originally built by the Germans in their post-World War I reparations to the French, and this meant that replacement trusses could be built up from the pieces salvaged from two or more usable spans.

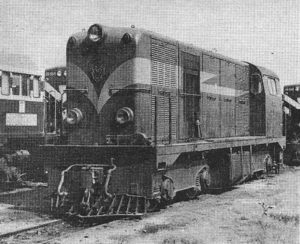

BB-902 is one of the six Alsthom 850 hp B-B diesels supplied to VNHX under the French assistance program (Paul S Stephanus)

The total cost of the rebuilding was 7.3 million dollars, a modest amount for restoring over 200 miles of demolished railroad. The cost of track materials was covered by a repayable 4.363-million-dollar US loan. On August 7, 1959, a train ran from Saigon to Huế for the first time in 15 years. Because of slow orders on track still being repaired, running time was 34 hours 25 minutes for the 600-mile trip. Before World War II it had been 26 hours.

The only retrenchment in the railroad at this time was the abandonment of the Saigon-Mỹ Tho line, Việt Nam’s first railroad. This line had been beset by water competition ever since it opened in 1885, and in 1958, its right of way and bridges were turned over to a highway project. “Water competition” in this case means sampans on the network of canals and sloughs in the delta. Of course, watercraft are an alternative all along the coast, but north of Saigon, this mode involves travel on the open sea and longer hauls, so it is not a serious factor.

The opening of the railway north of Ninh Hòa was a direct benefit to the rural people who inhabit the coastal valleys, and who have been alternatively wooed and terrorized in the course of this war. Periodically, these people must travel from their rice plots to town to buy clothes and the small luxuries of their frugal lives, and the railway fare is half that of the buses on the parallel Highway I. It also produces some benefits in freight transportation, although the economy is so disorganized by war and inflation that only the government and the military have much freight to move over and above the personal barter level of trade represented by a passenger with two rice baskets on a carrying pole.

Polished 4-6-0 was decorated to participate in 1961 opening of the branch line to An Hòa Industrial Complex. This locomotive was built in 1927, and today is stored serviceable at Tháp Chàm (Paul S Stephanus)

In 1961, the railway played an important part in one effort to move the economy out of this stage – the Nông Sơn development at An Hòa, southwest of Đà Nẵng. Here at the anthrcitious Nông Sơn coal mines, opened after partition shut off the former supply of coal from the north, the government of South Việt Nam hoped to develop a complex of medium industry, including chemical production, using the coal and coal-generated electric power as a base. A 12-mile branch of the railway was opened in 1961 from Bà Rén to An Hòa. The development was completely surrounded by Việt Cộng units, however, and after 1963 the coal it mined could not be transported out. In 1965, the whole Nông Sơn development was given up until such time as security improves, which in that region could be a long time.

Although the South Vietnamese enjoyed the services of a nearly complete rail network from 1959 to 1964, those years nonetheless were far from ideal. The guerrilla war increased in pitch each year, and the railroad, as an instrument of the government, became a target in the same way as do the lives of schoolteachers, policemen and local government officials. The object of the Việt Cộng was to destroy all connections between the government and the people, substituting the VC’s own shadow government in the rural areas. The availability of trains on the government’s railroad clashed with that goal, as it does today. Accordingly, trains were fired upon and derailed by mines, bridges were blown up, and stations were bombed. Although there were interruptions of service for days at a time in some sectors, the railroad managed to retain its integrity as a system. The only exception was the 84-mile Lộc Ninh branch, which operated through rubber-plantation country near the infamous Zones C and D – a territory the South Vietnamese Army had virtually ceded to the Việt Cộng. Operation on this route was discontinued as unsafe in 1961.

Rated at 900 hp and equipped for multiple-unit operation, 48 GE U8s are the mainstays of the railway (Paul S Stephanus)

The major improvement of the railroad during this period was the delivery in 1963 of 23 US-built diesels, along with diesel, car and wheel shop machinery, and 221 box cars, all of which were provided for by two US Development Fund loans. The new freight cars equalled about 25 per cent of the previous car capacity, and the diesels were able to handle most operation as traffic fell under war conditions. Ten new third-class passenger cars came from Australia under the Colombo Plan – an Asian self-help treaty for economic development.

During this period, the military situation for the South Vietnamese government grew steadily worse. The Việt Cộng began to roam the countryside in battalion or regimental strength, and the government’s soldiers were virtually driven from the field, leaving the railroad more and more exposed to the depredations of the guerrillas. The coup d’etat which resulted in the removal and assassination of Premier Ngô Đình Diệm in 1963 and led to a succession of ineffective military governments did not improve these conditions, and in fact the military position of the South Việts continued to decline until the arrival of US combat troops in 1965.

The coup de grace for the railroad came earlier than that, when a series of typhoons struck South Việt Nam in November 1964, and the resulting floods washed out large sections of the line. The railway had been able to keep up with the series of harassing derailments imposed by the Việt Cộng, but the combination of sabotage and nature proved too much. The guerrillas took advantage of the disruption of service to move in on abandoned areas and to do still more damage. By the end of 1964, more damage had been inflicted on the South Vietnamese railway system in a two-month period that in 15 years of World War II and the French War combined.

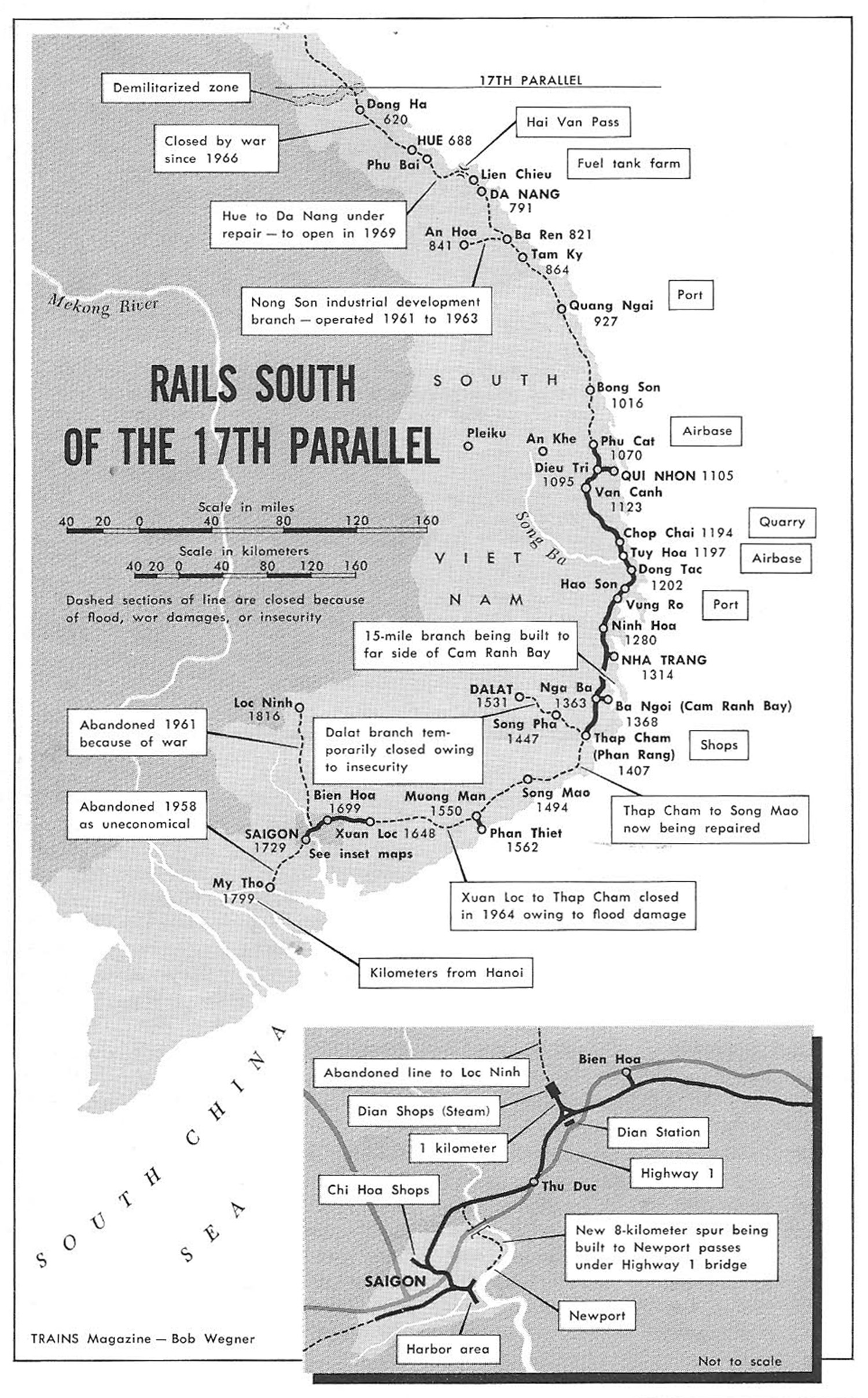

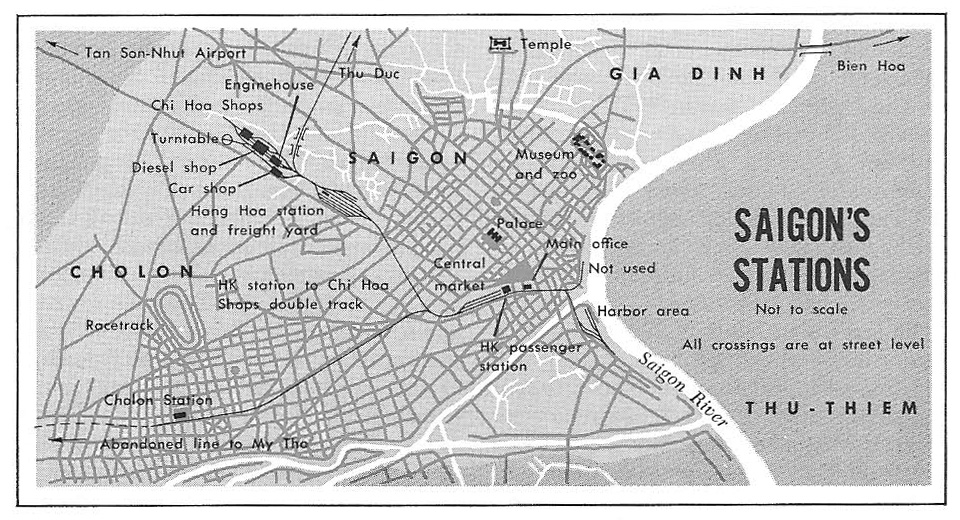

Since 1964, the operations of Việt Nam Hỏa Xa have been broken into segments. The details of these segmented operations can best be described by surveying them from north to south.

1. Đà Nẵng to Đông Hà

Symbolising a railroad slowly returning to life, an austere 1927 Cail 4-6-0 – dirty and bullet-ridden after a year and a half in storage in Huế – backs down the main line at Phú Bài in September 1968 with a work train to help open the road to Đà Nẵng. (photo by Paul S Stephanus)

After the 1964 typhoons, VNHX still considered this sector operational. During 1965 and 1966, a daily mixed was scheduled between Đà Nẵng and Huế, but the level of sabotage on this line was high, and the service was off more than it was on. Trains occasionally ran between Huế and Đông Hà in 1965 and 1966, but that sector has since been declared insecure and does not operate, although there are locomotives and cars in Huế which could handle this now isolated section, if necessary. Đà Nẵng is the principal US Marine port of supply, and the VNHX handles some local switching there. In connection with this supply base, the US has a fuel tank farm about 9 miles north at Liên Chiểu, and in 1966 and early 1967, a daily tank car train ran between Liên Chiểu and Đà Nẵng.

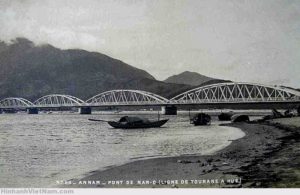

The Đà Nẵng to Huế section was closed from February 1967 until the end of 1968. The last through trains ran north from Đà Nẵng to Huế on February 1, 1967, and returned the next day. These trains were the regular civilian mixed, powered by a 4-6-0, and three diesel-powered military supply trains. They were the first trains since January 10, 1967 and the last for almost two years. On February 3 and 4, four bridges were blown between Đà Nẵng and Huế, causing enough damage to close the line for at least two months owing to a shortage of materials. Then in April 1967, swimmers floated a massive TNT charge down the Nam Ô river by night and obliterated one piling of the rail-highway bridge just north of Đà Nẵng, dropping two 80-meter spans into the water. At least two swimmers were blown up with the bridge, which was protected by 45 US Marine guards. This stopped all trains north of Đà Nẵng, including the Liên Chiểu tank trains.

Nam Ô Bridge, Đà Nẵng

The Nam Ô bridge was restored by November 1967 (in the meantime, a pontoon bridge carried highway traffic, including tank trucks, to Liên Chiểu), but not until July 1968 did work begin on restoring railroad service. At that time, a work train powered by a 4-6-0 began pushing south from Huế to meet two diesel-powered work trains coming north from Đà Nẵng, while US Army engineers assisted in the restoration of smaller bridges in this section. By December 1968, the northbound and southbound work trains were less than 20 miles apart, and only two small bridges remained to be repaired, with the through service from Đà Nẵng to Huế expected to resume in February 1969 or sooner, barring some calamity. Already, some military supply trains were operating north over the Hải Vân Pass to Lăng Cô, relieving the dangerous highway in this sector, and a 4-6-0 powered mixed train had begun making turns from Huế to the big US supply base at Phú Bài on the northern segment. With the work train and mixed operating from Huế, two 4-6-0s and a 4-4-0 on standby and for switching have been in steam regularly since October. Once the lines have been joined between Đà Nẵng and Huế, however, diesels will run through, and Huế’s steam power will revert to standby duties.

The problem in restoring a section such as the Đà Nẵng-Huế line is not an engineering one. The Việt Cộng are only rarely able to hit a big multi-span bridge such as the one over the Nam, and the smaller bridges they do attack can usually be repaired in less than 48 hours. The present work trains are more concerned with clearing brush from the track after more than 18 months of disuse than in repairing sabotage damage. The holdup instead is security and priorities. The VNHX is not an armed force. Its men are employed to run trains, not to fight. In spite of this, they have never refused to take out a train when ordered to do so, and they regularly operate under conditions which make them a prime target – such as handling military supply trains. From 1961 to mid 1968, 65 VNHX men have been killed and 1,341 wounded or injured in attacks on the railroad. VNHX officials take the view that if they are going to run trains under these conditions, the military they are serving should indicate the need for continued operation by supplying enough troops to protect at least some major bridges and military supply trains. If such troops are not available, or if the state of war in the countryside is so intense as to make regular operation unlikely, there is no point in rushing to restore service. However, the military, especially the US military, which has the resources to do things quickly when it wants to, now realizes the value of the railroad – or at least is more aware of its potential than in 1966-1967, when the first rush of the US buildup was largely truck-borne.

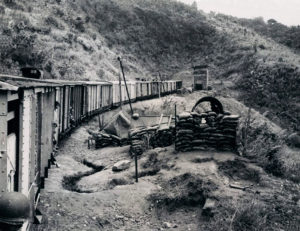

Huế-Đà Nẵng – Route of Risk, March 1969: It takes courage to commute from Huế to Đà Nẵng in South Việt Nam. The line is subject to attack and constant precaution is the order of the day. The track is lined on both sides with outposts, protected by barbed wire, bunkers and pillboxes. But at least the trains now run daily. They were blasted out of action by the Việt Cộng for over two and a half years, and only resumed service in mid-January of this year. (AP Newsfeatures Photo)

For six weeks after the February 1968 Tết Offensive, the highway pass between Đà Nẵng and Huế (the Hải Vân Pass) was closed; and only a few days after Tết, the US military was talking to VNHX about reopening the railroad. Army Engineer aid which had been stalled for months has since come forward. In September 1968, the military was given another demonstration by nature – Typhoon Bess hit Việt Nam, washing out the highway in several places. A few truckloads of dirt over the line at a tunnel mouth was the only consequence to the railroad. The lesson for the military is a short one and an old one: the railroad is no more vulnerable than the highway for regular mass supply movements (as opposed to the expensive tactical logistics resorted to only when bridges are out or roads and rails are otherwise impassable). In many cases, the railroad can be restored more quickly. It is much better engineered than the highway through the mountain passes, and has capacity that can replace dozens of trucks and drivers with a single train.

All of these factors, plus the good marks the Việt Nam government gets from the people when the train service is restored and military convoy traffic is kept off the highways, are working towards a higher priority for the railroad in military planning. This applies to all sections of the line, as we shall see. With this higher priority has come the “push” and the resources to restore the railroad.

2. Đà Nẵng-Phù Cát

This sector, which includes the new-in-1961 An Hòa branch and the important provincial capital of Quảng Ngãi, has been totally non-operational since the November 1964 typhoons, and is likely to be the last segment of the coastal main line restored to service. In 1966, many miles of line were cleared of track by US marine bulldozers, so that Marine tanks could freely operate down the right of way. The track material was to be stockpiled, but this was never done, and the rebuilding now will be a major job, probably not completed before 1970 under present conditions. Furthermore, during 1968, units of the ARVN, the regular South Vietnamese army, stole miles of track materials to make bunkers, and much of this found its way onto the local black market. VNHX local officials tried to stop the damage, but were powerless against the truckloads of men who swooped down on the idle line. Poor communications prevented them from reaching Saigon for help, and when VNHX sought the assistance of the provincial chief, he was “unavailably sick.” Province chiefs are ARVN officers. Between them, the Marines and the ARVN have done damage to this sector that will take longer to repair than most of the pillaging of the Việt Cộng.

In this sector is a work train stranded in the 1964 typhoon at Bông Sơn, while the train was on its way from Quy Nhơn to Đà Nẵng. In 1968, the US Army sent trucks to Bông Sơn and carried the railroad cars back to Quy Nhơn, where they were restored to service. The diesel is still there, and could be used to move a work train south towards the present end of operational track at Phù Cát if a decision is made to proceed with this reopening. Bông Sơn’s coastal valley is one of the most important rice-producing areas in central Việt Nam.

3. Phù Cát-Quy Nhơn-Tuy Hòa

A 900-year-old temple, built by Hindu Champas, looks down on a 1959 Alsthom diesel moving off a standard German 50-meter truss bridge along the old Trans-Indochina line near Quy Nhơn in 1967. (Paul S Stephanus)

After the 1964 typhoons, the entire line from Đà Nẵng to Nha Trang was closed at first, but Quy Nhơn soon revived as a switching operation because of its status as a port. Quy Nhơn is the seaward anchor of Highway 19, the vital route to the interior which supplies the big US Army installations at An Khê and Pleiku, and the port handles heavy traffic. In addition, a major new jet fighter base was built 21 miles northwest at Phù Cát, to which VNHX runs a daily supply turn from Quy Nhơn. During the construction of this base, a quarry train was also operated. This train brought rock fill from a point 8 miles south of Phù Cát for dumping at the base site. This activity alone saved the US a large number of dump trucks and drivers which would have clogged Highway 1 in that sector. The supply train handles, among other things, ammunition and fuel, and would be a prime target on its daily 42-mile round trip, but the Quy Nhơn area is relatively secure, since it is patrolled by both US and Korean troops.

During the 1968 Tết Offensive, a bridge was damaged by a fire in the US Army pipeline that used the bridge, but the structure was soon restored. The lack of a serious attack on the supply train is an indication of the excellent local security conditions.

The Quy Nhơn operation of VNHX also included a mixed train to Vân Canh, about 22 miles by rail southwest of Quy Nhơn. This train served mainly the civilian “strip” development which has grown up along Highway 1, where it parallels the main line west of Quy Nhơn. During 1968, work trains operating south from Quy Nhơn and north from Tuy Hòa restored service all the way to Tuy Hòa. By November, military freight was being carried over this newly-reopened section by a down-one-day, back-the-next turn from Quy Nhơn. Travelling slowly to reduce damage in case of mining, the train leaves Quy Nhơn every other day at about 8am and arrives at Tuy Hòa, 66 miles, in 9 hours – an average of about 7mph. On September 24, shortly before the line was reopened, the diesel locomotive of a work train was derailed by a pressure mine. This kind of activity must be expected from time to time as long as the guerrilla war continues. It does not prevent operation.

4. Tuy Hòa area

Việt Nam’s longest bridge – containing 21 50-metre spans erected in 1936 – carries the Trans-Indochina main line and Highway 1 across the River Ba. A GE U8 moves quarry stone to Tuy Hòa airbase. (Paul S Stephanus)

Tuy Hòa’s rail terminal, like that of Quy Nhơn, was isolated by the 1964 disasters, but was soon revived because of the construction of a big new US airbase at Tuy Hòa South. The new town of Tuy Hòa sits on the north bank of the River Ba, which the railroad and Highway 1 cross on a bridge consisting of 21 50-meter spans, the longest bridge in Việt Nam. Several miles south of the river is the airbase, and a little more than a mile north of Tuy Hòa station is the Chóp Chài quarry, source of the grading material used to construct the base. The distance from the quarry to the base is a little over 5 miles, and since 1966, a quarry train has been running between these points – first to build the base, then to build a railroad bypass around the base and to provide rock for work on Highway 1 south of Tuy Hòa. A daily commuter train runs from Tuy Hòa to the airbase, carrying Vietnamese civilians to and from their jobs at the installation. At the height of the airbase construction, quarry trains ran up to four or five times a day, handling 14,000 metric tomes of rock in one week, and a diesel unit was assigned solely to this duty. Now, the train runs about eight times a week, and the same diesel handles both the quarry and commuter trains, releasing the other unit normally stationed at Tuy Hòa for the rapidly-expanding motive-power demands caused by the present line reopenings.

5. Tuy Hòa-Nha Trang

Since 1964, service north from Nha Trang had been knocked out by a blown concrete bridge north of Nha Trang, as well as by track damage, but in July 1967, service was restored. A daily mixed turn from Nha Trang to Hảo Sơn began carrying an average of 250 persons per day, an indication of the demand for railroad service where lines can be reopened even in this sparsely settled stretch, with the service ending “nowhere” at Hảo Sơn, a gutted railroad station without a town on the north side of the pass at Cape Varella.

An armored car (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

The success of this reopening in 1967 undoubtedly pointed the way for the more ambitious reopenings undertaken in 1968. The 5-mile gap between Hảo Sơn and the operating segment from Tuy Hòa to the airbase, however, presented two serious obstacles. First, the runway of the airbase cut across the VNHX main line. This was bypassed by a line relocation during 1968. Second, the through truss bridge at Sắc Đéc was made in the United States in 1967 and test-assembled at Dĩ An shops early in 1968. It was knocked down and shipped over water to Nha Trang, then moved by rail to Sắc Đéc, assembled at the scene and completely installed on December 4, 1968. Continuous rail service was still available in December 1968 from Quy Nhơn to Tháp Chàm, a distance of about 174 miles along the central coast. This segment of the line passes through the US Army’s new port development at Vũng Rô, just south of Hảo Sơn. Here, two De Long piers have converted a former wilderness beachhead on the shore of Cape Varella into a “little Cam Ranh,” which is now one of the five greatest ports of Việt Nam for military supplies. Up to now, the only role the segmented railroad could play for Vũng Rô was to lend its right of way for the pipeline which runs from Vũng Rô to the Tuy Hòa airbase, but with the line reopening, it should be possible for the railroad to take over some of the massive truck-hauling job now going on between Tuy Hòa and Vũng Rô.

6. Nha Trang-Tháp Chàm (Phan Rang)

Until 1968, the daily mixed Nha Trang-Tháp Chàm, and its connecting daily mixed over the Đà Lạt branch, had provided the safest and most continuous and stable service on the VNHX since the 1964 disaster. Tháp Chàm means simply “Cham Temple,” and refers to the spectacular Champa ruins on the hill above the shops. These relics of the old Hindu Champa civilization are also found at Quy Nhơn, Tuy Hòa, Nha Trang and other places on the coast, and all predate William the Conqueror’s reign in England. The ruin at Tháp Chàm, however, is the most flamboyant in architecture. The last remaining Cham people are now concentrated in a few fishing villages near Phan Rang and Phan Thiết, and the Tháp Chàm railroad station is actually there to serve the major town of Phan Rang. It is also the location of a locomotive and car shop.

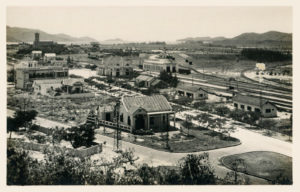

Nha Trang Station (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

Nha Trang is a seaside resort where French villas line the curving beach road, overlooking a bay surrounded by green mountains and dotted with islands. Today it is also a military port, and the regal old Grand Hotel is headquarters of Field Force One, the US Army’s Corps Command for central South Việt Nam. The railroad takes a circuitous route west and then south from Nha Trang, bypassing a cluster of mountains that separate Nha Trang from Cam Ranh Bay. At Ngã Ba, a 3-mile branch line takes off for the shore of the bay. This freight-only branch is operated by the last remaining “Camion rail” in service – a 1940 GMC truck engine converted to haul light loads over the railroad over sections of track wrecked by previous wars.

However, the branch reaches the wrong side of the bay to serve the massive US port development, although it is now handling a supply train from Ba Ngòi’s barge dock to the Korean Army base camp at Ninh Hòa. A quarry train for a Highway 1 project near Nha Trang also originates on this branch. Both of these trains are in addition to the Camion rail on the Ba Ngòi branch, and are products of the last months of 1968 and the increased military awareness of the railroad. Even more to the point, though, is the new 15-mile branch line now being built to the opposite side of Cam Ranh Bay, on the peninsula where the main US port development is located. This line was made possible when a permanent bridge with a rail section was installed by the United States to replace the pontoon bridge to the peninsula, and will afford direct rail distribution to the entire coastal tributary area of this massive port, whose docks and depots supply units as far north along the coast as Quy Nhơn.

From Ngã Ba, the line goes over flat, dry territory to Tháp Chàm. The mixed is almost always diesel-powered, but on rare occasions, one of the stored-serviceable 4-6-2s at Nha Trang or Tháp Chàm has substituted (These engines occasionally have been used on work trains). With the extensive line reopenings, steam power may see a more extensive pinch-hitting role as diesels are spread thinner. Beginning in mid-1968, the Nha Trang-Tháp Chàm mixed was the subject of stepped-up Việt Cộng harrassment, with minings and occasional interruptions of service lasting two or three days. Because of this harassment, trains have been running slower, and a power shortage caused by the minings and the new services has made it necessary temporarily to cut back both the Nha Trang-Tháp Chàm mixed and the Nha Trang-Hảo Sơn scheduled to an every-other-day basis. Six mine-damaged diesels were under repair at Tháp Chàm as late as early December 1968, helping to explain this service cutback, which should be alleviated as you read this.

7. Đà Lạt branch

Cog Railway to Dalat (photo by Paul S Stephanus)

Until the fall of 1968, the Đà Lạt branch was operated as a connecting service of the Nha Trang-Tháp Chàm mixed. The train from Nha Trang would arrive in the morning in time to connect with the diesel-powered Sông Pha turn, and would wait for the Sông Pha train to return before going back to Nha Trang. In fact, sometimes, both turns were handled by the same equipment. Now, owing to the stepped-up Việt Cộng molestation between Sông Pha and Đà Lạt, the whole Đà Lạt branch has been temporarily shut down.

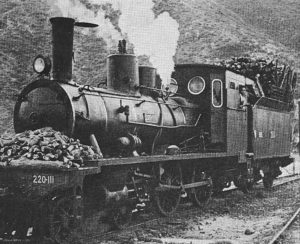

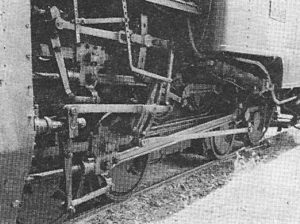

When the Đà Lạt branch is operating, it is worked in two sections. The Tháp Chàm to Sông Pha turn takes traffic to and from the heavily graded rack section. West of Sông Pha to Đà Lạt, steam rack-and-adhesion locomotives hoist traffic up grades of as steep as 12 per cent to Đà Lạt. Despite the temporary line closing, VNHX is going ahead with an order for GE rack diesels for this line, but they are not expected to arrive until late 1969 or early 1970.

Đà Lạt is an extremely important traffic point, because of the large vegetable crop grown in the pleasant climate of its 4,500-foot elevations. The US Army has become one of the largest customers for Đà Lạt vegetables for its mess halls, and there is substantial civilian consumption which the extension of service on the main line should increase. For braking reasons, cars of vegetables can be handled only four at a time down the rack, and the cars must be equipped with the rack braking gear. Consequently, the steam rack locomotives run something of a shuttle service down the rack to Sông Pha, as traffic demands.

Cog Railway to Dalat (photo by Paul S Stephanus)

The adhesion-only section of the Tháp Chàm to Sông Pha branch is 24 miles long, and rises in elevation from near sea level to about 500 feet, with a few 1.5 per cent grades. The next 30 miles include three rack sections on 12 per cent grades, which are tackled at walking speed. The average speed over the whole rack-and-adhesion section from Sông Pha to Đà Lạt is 10 mph. The scenery is breathtaking as the train climbs 4,500 feet into the sky, surrounded by deep forests and rushing mountain streams. The Việt Cộng are in those forests, but until 1968 they did not usually touch the rack trains. A public relations problem may have been what caused the Việt Cộng to stay away, because the trains carry no military freight except vegetables, and are the only practical access to and from Đà Lạt for civilians wishing to trade in the lowland.

Whatever the reason for the tacit truce, however, it collapsed after the Tết Offensive. About 30 times in 1968, small (6-to-12-meter) I-beam bridges were damaged by saboteurs and repaired, usually in 4 to 48 hours. Most of the trouble was in a 6-mile section of inaccessible jungle along the 12 per cent grade north of Sông Pha. Here, one small bridge has been damaged eight times. In addition, before the line was closed, trains were attacked several times. Swiss-built Abt-rack engine 40-302 was hit twice. In May 1967, before attacks became commonplace, a train powered by 40-302 was stopped, crew and passengers were driven away, and a charge was placed in the 302’s cab. The damage was quickly repaired at Đà Lạt, and one wonders whether the sapper who did the job was just a little too afraid of the hissing “Hỏa Xa” to place his charge where it would have done real damage – among the bewildering valve motion and rack gears of the four-cylinder Abt drive system. In any case, 302’s next encounter was much grimmer. On September 24, 1968, the Communists attacked an up train powered by 40-302 with RPG rocket launchers (a Soviet bazooka). Three crewmen died and 302 was seriously hit. She is now at Đà Lạt for repairs.

8. Tháp Chàm-Mường Mán-Phan Thiết

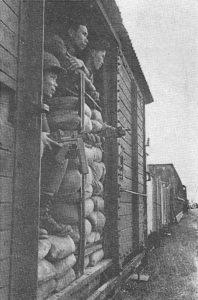

Railway Security – ARVN security detail jumps from a train to check security on a run north of Saigon (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

The line between Tháp Chàm and Mường Mán suffered heavily in the 1964 floods, but now a work train is pushing forward to link up with the isolated locomotives and cars at Mường Mán. In December 1968, the work was proceeding south from Tháp Chàm as far as Sông Mao, and the plan was to start a meeting work train north from Mường Mán. This section by itself will not be too significant from a traffc standpoint until the gap between Mường Mán and Xuân Lộc is closed, permitting through service to Saigon. But it will give access to the pool of rolling stock at Mường Mán. The 7-mile branch to Phan Thiết is in operable condition and has seen occasional movements; and Phan Thiết, a town of 100,000 population, should generate civilian travel.

9. Mường Mán-Xuân Lộc

This segment can be opened, providing through service to Saigon, whenever sufficient security forces are made available. The ARVN has allocated enough forces to protect the work train, but the province chief in the area wants assurance from the assurance from the US that a reaction force will be provided in case of a major attack on it. With all the military commitments and contingencies currently possible in the Saigon area, the US Command has not been willing to give such an ironclad promise.

10. Saigon area

Although the Saigon sector has involved only short runs to date, it is the busiest part of the system and is becoming still busier. In 1968, 2,500 tons a week were moving from the Saigon River docks (not including those at Newport, which will be seved by a branch now under construction), mainly to Dĩ An, base camp of the US Infantry Division; the big airbase at Biên Hòa; and the new Hố Nai yard serving the huge Long Bình supply complex stretched out along Highway 1 near Biên Hòa. Two trains a day were handling this traffic by October 1968, with some trains going on to Xuân Lộc, the 11th Armored Cavalry base camp at the current end of operable track north from Saigon. Plans were progressing to construct about 12 miles of spur lines through the Long Bình complex, and a gravel train was inaugurated from Thủ Đức to Xuân Lộc for improvements on Highway 1. The 2,500 tons per week figure is double that for a year earlier, and does not include the gravel trains.

Further increases in business are expected, now that VNHX has assumed the job of port clearance for Saigon, which includes decisions as to how freight will be moved off the docks. The US Command had taken this job from the railroad and immediately suffered a massive cargo pilferage problem, which has caused an aid program scandal in Congress. The railroad’s experienced personnel never had such a problem, and it is hoped that by returning port clearance responsibility to VNHX, the pilferage will be stopped. Incidentally, by any standard, and not just by comparison with the usual situation in Việt Nam, the railway has been free of corruption.

Saigon’s Chí Hòa Depot (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

Until the Tết Offensive disrupted the life of Saigon, passenger trains also ran to suburban Chợ Lớn and Thủ Đức. The main patrons of the Chợ Lớn train were schoolchildren, but the temporary closing of Saigon’s schools, which are being used to house refugees, has ended this service for now, and the Thủ Đức trains are not run because of the danger to passengers in this beseiged city.

Saigon has the two heaviest shops on the system – the diesel shop in the central city at Chí Hòa, and the steam shop 13 miles out at Dĩ An.

Because of these shops, nearly half of the diesel locomotives on the system are kept at Saigon and are barged up-country as needed. If the link from Xuân Lôc to Mường Mán is completed, this slow barging process can be ended, and availability of locomotives up-country will automatically increase. In April 1967, a team of Việt Cộng sappers broke into the Chí Hòa compound and damaged 10 locomotives and a heavy wrecking crane with satchel charges. The shops repaired the damage, and the engines were excess to the system’s needs at that time, so no operating difficulties resulted from this damage. With the time coming for the line to open – perhaps all the way to Huế – the day should be passing when lines of diesels at Chí Hòa sit idle waiting for work and inviting attack. [NB – To preclude a repeat of this calamity, Saigon’s large stockpile of locomotives has now been scattered to several points, instead of being lined up at Chí Hòa shops. Demands for more power up-country should soon end the surplus].

Dĩ An has little work to do now, but an overhaul of Esslingen-built rack engine 40-306, which included stripping her to the frame and removing her boiler, was completed. Reassembled, she was barged up the coast to Ba Ngòi and forwarded by rail to Sông Phà, in time to replace the rocket-blasted 302.

An early goal of the massive revival under way is normal operation over a large part of the system.

Train arrival at Saigon Station (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

“Normal operation” in Việt Nam is still not normal by the standards of any nation not enmeshed in a guerrilla war. There simply are not enough troops to guard every bridge, let alone every mile of track. One man with a few pounds of TNT can slip it along the rails, and with a simple electronic detonator (a flashlight battery and some of the Army field wire scattered so freely around Việt Nam by the Signal Corps) can derail a train while he watches from a concealed position in the bushes. Such incidents will continue to occur, but probably not often enough to disrupt service seriously. The usual result is a 12-to-24 hour pickup job and some time in the shop for the equipment. To date, repairing equipment to stay ahead of this damage has not been difficult, although conditions will get tighter as traffic picks up with the reopening of the line. However, shop procedures can be speeded, and as more rail lines open, it will become easier to get equipment to and from repair points.

Civilian trains are equipped with a radio to call for help, but they do not carry armed guards unless there is military freight on board. Actually, soldiers are more of a curse than a blessing on a civilian train, because they draw fire. The civilian trains do have passive defenses, though. The locomotive pushes ahead of it a flat car intended to detonate pressure mines in sensitive regions, although a clever sapper can circumvent this by placing the trip a car-length beyond the charge. Passenger trains usually have a few hopper cars [Recently box cars have been substituted for hoppers in this duty owing to the demand for hoppers in gravel and rock trains] behind the locomotive to take the brunt of a derailment in which the charge goes off ahead of the train or under the engine.

A military train is usually interspersed with armored cars armed with .30-caliber machine guns, mortars, grenade launchers, automatic rifles, and riflemen. The object is to have enough force on hand to hold off an infantry attack until planes and/or helicopters can arrive with assistance.

“Wickhams” came from Malaya in 1962 and are used from time to time for train-escort and mine patrol duty (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

No military trains have been overpowered in the present conflict, but during the French war, some grisly instances occurred. One train was trapped by mines in a deep rock cut near Mường Mán. Gasoline was thrown over the edge of the cut into the armored cars and ignited, burning the guards to death. The Việt Minh then went through the rest of the train, shooting every French Union soldier in sight and lecturing the civilians on board about the dangers of adhering to the regime. The better communications and helicopter mobility of today, coupled with the relative weakness of VC units in the central region, should avert such attacks; but nevertheless, the guerrillas can pick the time and place where they will strike, and anywhere they appear in force, they are able to hold temporary sway. The only question is whether they are willing to sacrifice the lives and weapons involved in attacking a particular target. That the railroad draws its share of attacks indicates that the Việt Cộng continue to regard it as important.

The importance of the railroad to the civilian population is indicated by the patronage of the trains. The train is not only cheaper, but safer than the buses on the parallel Highway 1. The Việt Cộng sporadically mine the highway, apparently trying to blow up military vehicles, but disregarding the fact that, just as often, it is a crowded Lambretta or Renault microbus that sets off the charge, with hideous results. The attacks on the railroad have been less lethal to civilians, although the last car of the Đà Nẵng-Huế train was blown up in 1966, killing nine civilians. The Đắk Sơn Massacre brought home to many Americans the lesson that one trick in the Communist book is to kill civilians indiscriminately on calculated occasions, to destroy faith in the government, or to increase pressure for surrender at any price.

A General Electric BB diesel-electric locomotive passes Phù Cát in October 1971 (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

The military importance of the railroad is increasing dramatically as more of the line is opened. Highway 1 is now carrying most of the burden of supplying the chain of coastal military installations from the string of military ports. The heavy traffic has beaten the pavement to pieces, making speeds over 20mph impossible over long stretches. Where the pavement is gone altogether, slippery laterite clay sends trucks skidding into ditches after a rain. The dust clogs air filters in dry weather. In short, the truck lift is a costly operation. It did a good job in the initial tactical situation that accompanied the massive buildup of US and allied troops since 1965, but now that the railroad is being restored, the load can be taken off the hot rubber and the highway can be returned to the Vietnamese, who must now duck aside every few minutes for another rampaging convoy.

Whatever the rest of the world thinks, VNHX officials are clearly anticipating postwar operations in the foreseeable future. Equipment is being shopped and set aside for the day when through trains again run from Saigon to Huế carrying diners and sleepers. In fact, some first-class cars and a diner were rolled out for the dedication of the Hố Nai freight station in 1968, and VNHX officials turned down an offer of US Army helicopter transportation in order to ride again in VNHX’s former luxury. It is anticipated that new railcars will be purchased to cover local services after the war. New freight tariffs and fare structures have been designed to meet the expected competition of a rebuilt Highway 1. Thus, we can all look forward to the time when the “conveyance which runs by fire” will be an instrument of peace.

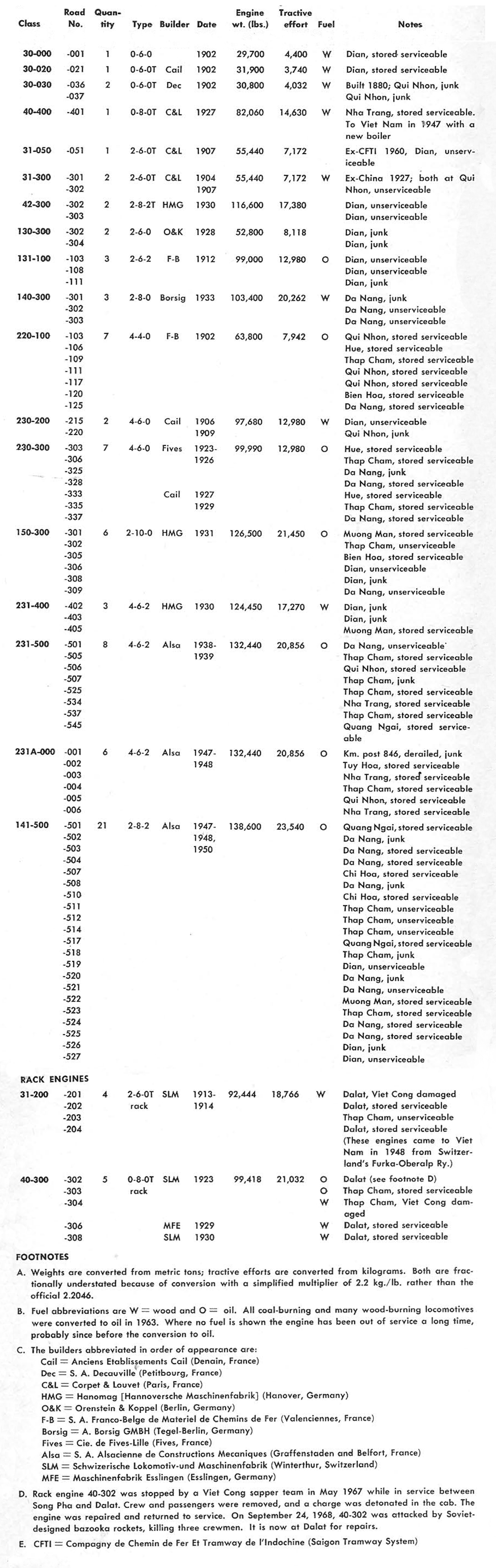

SOUTH VIỆT NAM’S DIESELS AND MOTOR CARS

Class BB901

Alsthom (France) 1959, 850hp B-B diesel-electric locomotives

Alsthom diesel-electric locomotive No BB902 at Chí Hòa Depot (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

|

BB901 Central BB902 Saigon BB903 Saigon

|

BB904 Central BB905 Saigon BB906 Central

|

Class BB907

General Electric (US) 1963, 900hp, B-B model diesel-electric locomotives, 114,000 pounds

General Electric B-B diesel-electric locomotive No BB921 on the Nha Trang-Tháp Chàm mixed (Paul S Stephanus)

|

BB907 Saigon BB908 Saigon BB909 Stranded at Bông Sơn BB910 Đà Nẵng BB911 Đà Nẵng BB912 Central BB913 Đà Nẵng BB914 Central BB915 Mương Mán BB916 Central BB917 Đà Nẵng

|

BB918 Central BB919 Đà Nẵng BB920 Central BB921 Stranded at Bà Rén BB922 Central BB923 Mương Mán BB924 Central BB925 Mương Mán BB926 Mương Mán BB927 Đà Nẵng BB928 Saigon BB929 Central

|

Class BB930

Identical to Class BB907 but built in 1965

General Electric B-B diesel-electric locomotive No BB937 (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

|

BB930 Central BB931 Central BB932 Stranded at km 1616 BB933 Saigon BB934 Mương Mán BB935 Mương Mán BB936 Central BB937 Central BB938 Saigon BB939 Central BB940 Central BB941 Saigon

|

BB942 Central BB943 Saigon BB944 Saigon BB945 Saigon BB946 Saigon BB947 Saigon BB948 Saigon BB949 Saigon BB950 Saigon BB951 Saigon BB952 Saigon BB953 Saigon BB954 Saigon

|

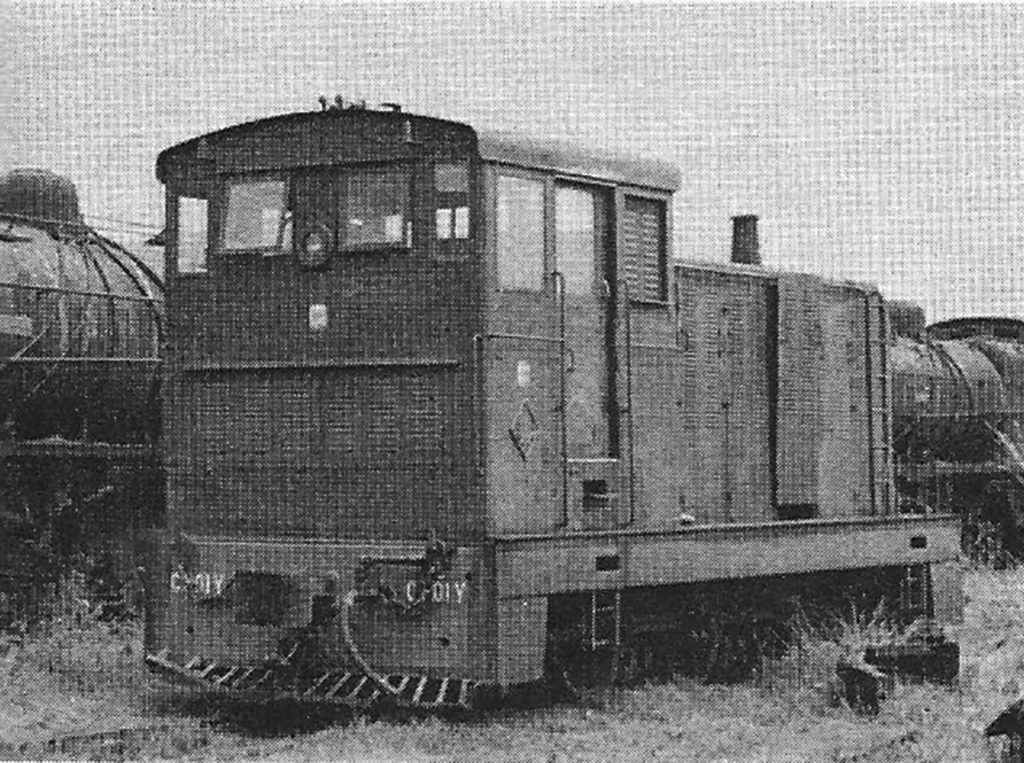

Class 1988

Plymouth BB diesel-hydraulic locomotive No 1993 (photographer unknown)

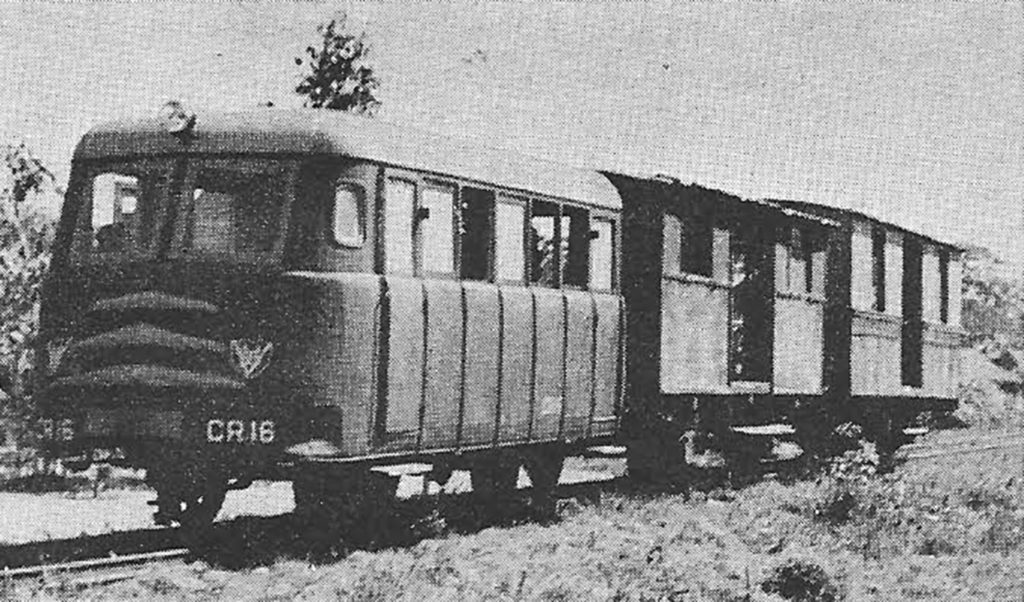

US Army-owned Plymouth (US) model CR-8 1,000hp dual-engined diesel-hydraulic locomotives built in 1964; 114,400 pounds; until 1968 used and lettered for Royal State Railways of Thailand; to enter switching service in Saigon, relieving road units for use elsewhere; now lettered US Army; road numbers 1988-1997, at Saigon.

Class C301Y

Bandet, Donon & Rousell (France) 1955; 300hp 0-6-0 diesel-mechanical locomotives supplied to VNHX by US Army in 1957; road Nos C301Y-C302Y, at Saigon

Two French direct-drive diesel units, which switch at Dĩ An and Chí Hòa, were brought to Việt Nam in 1957 (Paul S Stephanus)

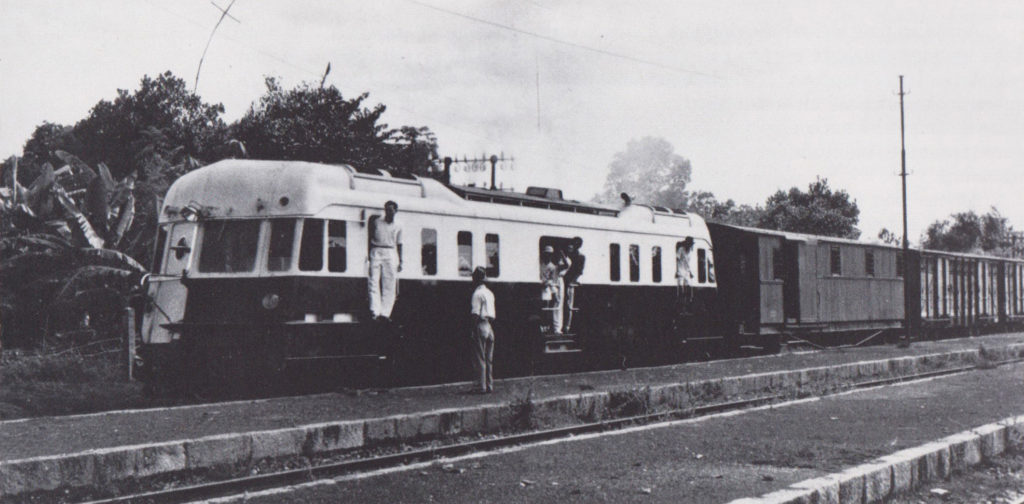

Class B2-301Z

Renault (France) 300hp “Autorail” diesel-mechanical railcars, 1940

A Renault “Autorail” diesel-mechanical railcar (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

|

B2-301Z Huế, stored unserviceable B2-302Z Huế, stored unserviceable B2-303Z Saigon, junk

|

B2-304Z Saigon, stored unserviceable B2-305Z Saigon, stored unserviceable B2-306Z Đà Nẵng, junk

|

Rail trucks

Camions rail, or rail trucks built from 1940 GMC trucks, were used over sections of the line damaged during World War II and the French war. One still serves on the Ba Ngòi branch. (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

VNHX still has 10 “Camions rail” (rail trucks), which it built in 1940 using 60 hp GMC truck engines. These units operated over war-damaged sections of the line demanding light axle loadings. Only one is now working pulling one or two freight cars over the Ngã Ba-Ba Ngòi branch, meeting the Nha Trang to Tháp Chàm mixed. Surviving are four similar “Drasire” cars which no longer operate. These were built in 1940 and also have 60 hp GMC engines, but they have space on board for passengers or sectionmen.

Wickhams

These armored rail motor cars came to VNHX from the Malayan railway system in 1962. They were built originally by the Wickham company in England and are used to patrol track for mines and ambushes and to accompany trains in dangerous sections. Formerly they ran ahead of trains, but now three or four usually follow an escorted train to rush up with reinforcements in case of an attack. Twelve units, 6001-6012, have 60 hp engines; 18 units, 8001-8012, 8012A, 8014-8018 (there’s no No 13) are 80 hp. Each has gunports in the sides and a turret in which a .30-caliber Browning air-cooled machine gun may be mounted.

NOTES

Five sector designations are used in this roster. The Huế, Đà Nẵng and Mương Mán isolated local areas are self-explanatory, although the Huế and Đà Nẵng sectors may be joined as you read this, and work has been under way to bring out the isolated Mương Mán engines to Tháp Chàm in the Central sector. The Saigon sector includes the branches in the Saigon area and the operation out to Biên Hòa and Xuân Lộc. The Central sector includes the continuous line now open from Tháp Chàm to Quy Nhơn and branches.

At present, power can be moved between these isolated sections only by coastwise barge. Nine units were barged from Saigon to the Central sector in 1968, and one was barged from the Central to the Saigon sector for repair. As of early December 1968, 22 of VNHX’s 54 road diesels (the Alsthoms and the GEs) were out of service with different degrees of Việt Cộng damage. Only by continual repair effort against this harassing damage (most of it minor) does the road keep operating.

All horsepower ratings are European gross ratings. The 900 hp GEs, for example, would be 810 hp by US net horsepower for traction standards.

This is the second of two articles on the railways of South Việt Nam written in 1969 for Trains magazine by Jerry A Pinkepank – to read the first article, click here

Tim Doling is the author of The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, Bangkok, 2012) and also gives talks on the history of the Vietnamese railways to visiting groups.

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group Rail Thing – Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam for more information about Việt Nam’s railway and tramway history and all the latest news from Vietnam Railways.

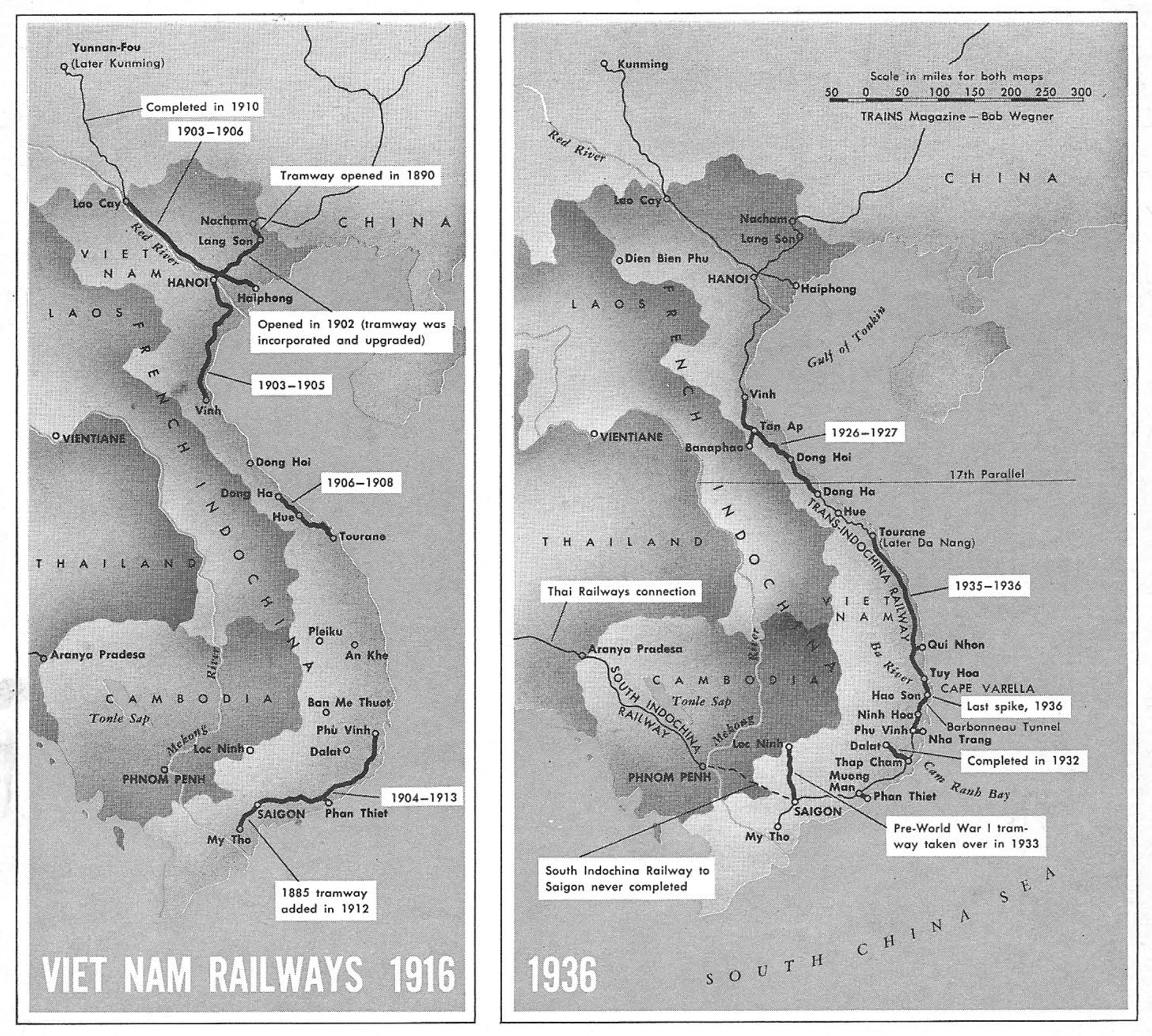

An examination of the Việt Nam railway system logically divides into two parts: the history under French rule, when all of Indochina, including what is now North and South Việt Nam, Laos and Cambodia, were under a single political sway, and a Frenchman dreamed of linking all with a single meter-gauge rail network that would reach by interchange all the way to Singapore and maybe Burma and India; and the history of South Việt Nam’s railway in the present conflict. A fundamental political event in Southeast Asia occurred in 1954, when the Geneva agreement ended French rule of Indochina and partitioned Việt Nam at the 17th Parallel, cutting the Trans-Indochina Railway near its center and setting up South Việt Nam and its railway, the VNHX, as separate entities.

An examination of the Việt Nam railway system logically divides into two parts: the history under French rule, when all of Indochina, including what is now North and South Việt Nam, Laos and Cambodia, were under a single political sway, and a Frenchman dreamed of linking all with a single meter-gauge rail network that would reach by interchange all the way to Singapore and maybe Burma and India; and the history of South Việt Nam’s railway in the present conflict. A fundamental political event in Southeast Asia occurred in 1954, when the Geneva agreement ended French rule of Indochina and partitioned Việt Nam at the 17th Parallel, cutting the Trans-Indochina Railway near its center and setting up South Việt Nam and its railway, the VNHX, as separate entities.