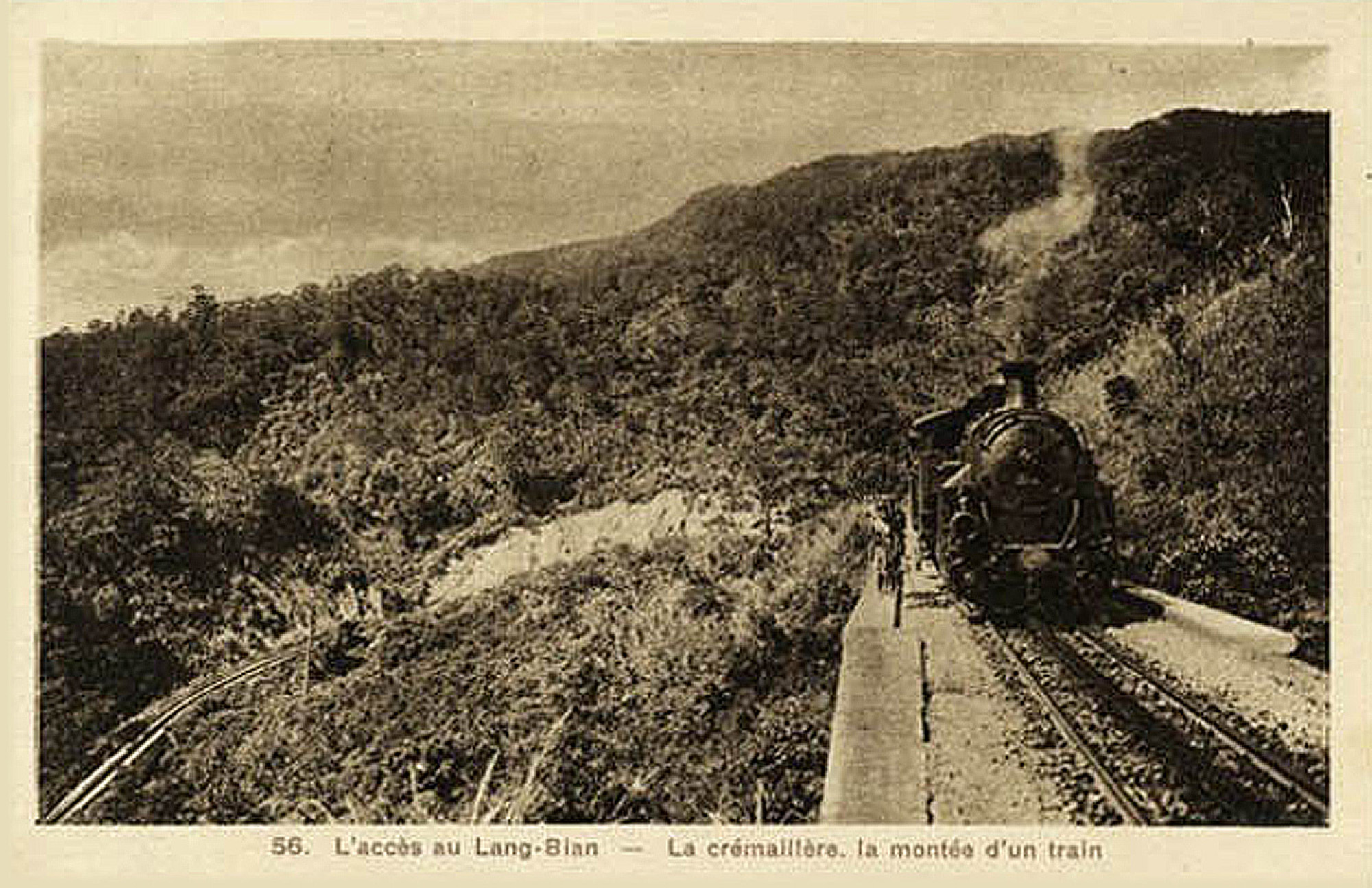

Access to the Lang-Bian plateau – The Cog railway, getting on a train

At around 10pm on Friday 13 May 1938, the 8pm overnight train from Đà Lạt to Saigon, hauled by SLM HG4/4 0-8-0T cog locomotive No 708, derailed at Kabeu during its ascent from Bellevue. The entire train rolled some way down the mountain, crushing a 4th class carriage and leaving 15 dead and around 20 injured. This is an English translation of an article criticising line safety and management published in L’Effort: journal hebdomadaire, Hanoï, on 17 and 24 June 1938.

“Nice view”

Ar-Lac, Da-Bac, Diêu Trì… so many names, so many catastrophes. And now, Bellevue. This is the fourth fatal rail disaster in less than 10 months. The eighth, if we also count derailments which caused only material damage.

Nice view! I can’t help but think about the cruel irony of these words as I prepare myself for the Dantesque spectacle I will see later. In the meantime, standing on the platform of the rear carriage of a winding train which chugs me towards the scene of the disaster, I admire the long serrated cog rail, located between the running track, which permits trains to climb the mountain.

It’s a beautiful route, admirably constructed. Think about it! This gradient is 12 millimetres per metre!

Of all the railway lines in Indochina, the Tourcham-Đà Lạt cog railway line is the toughest. But also the best built. It was designed and built by German and Swiss engineers, it’s said.

On this track, we have the impression that the risk percentage should not be higher than that of any other railway lines, if the rolling stock was a little less dilapidated. Just a little. But our railroad bigwigs, having been warned about it, rarely risk their own precious persons by travelling on rolling stock which has reached “the limit of its resistance” (Lefèvre dixit), and apparently don’t believe it necessary to safeguard others, namely the passengers. On a gradient of 12mm/m, they put into service eight antediluvian locomotives, all dating from 1932 or before.

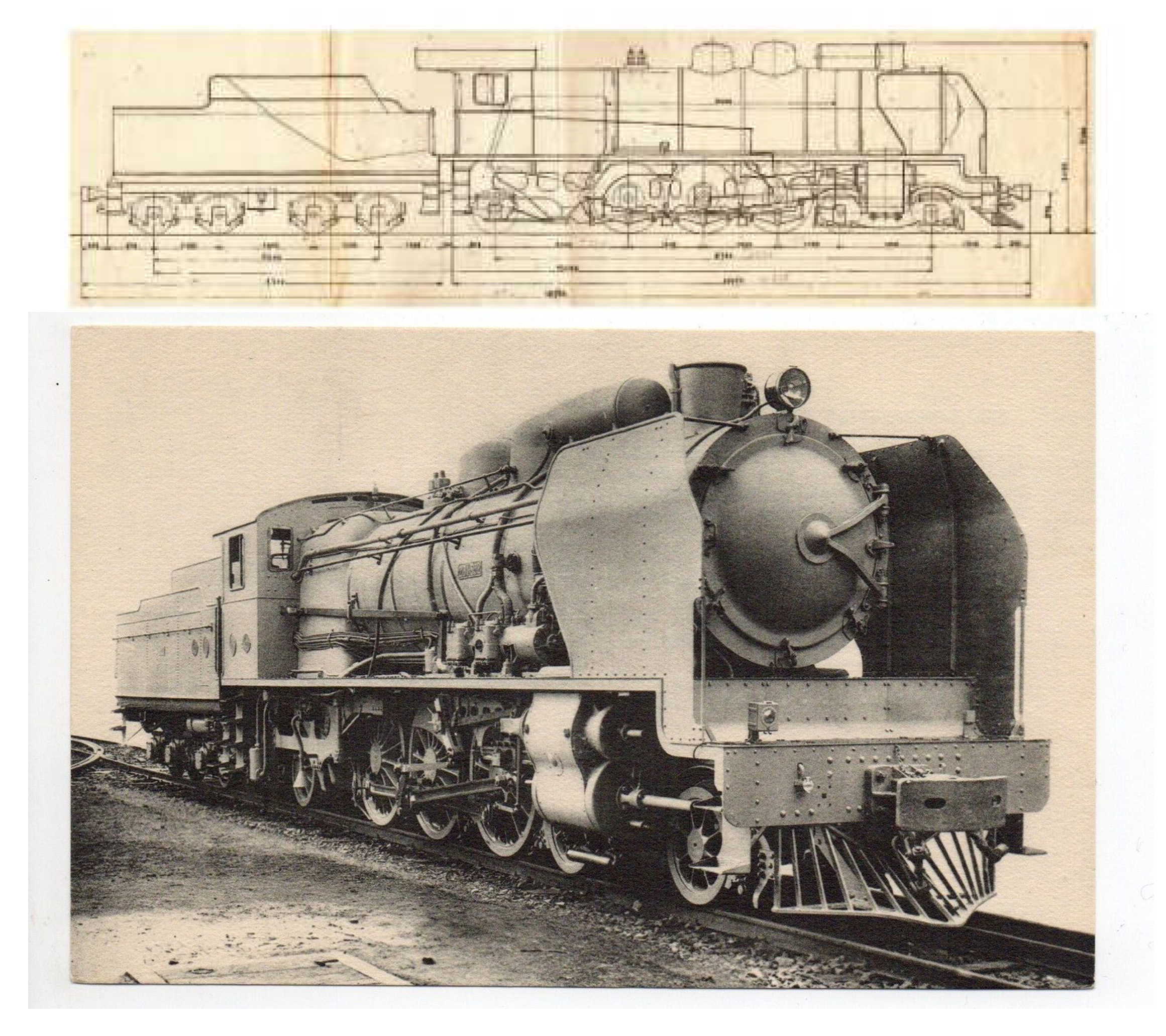

Ligne de Krongpha à Dalat – Voie à crémaillère – Krongpha-Dalat line – rack rail

We arrive at Krôngpha. From there, we’ll have to travel by road to reach the site of the disaster. The fireman of the train I travelled in, standing on the station platform, smokes a cigarette nervously. His face is pale. He doesn’t seem very communicative. And that’s a shame. Because I’m curious to know his impressions. Fortunately, the driver is more talkative.

“We must say, Mr Journalist, that our nerves have never been more strained. Stretched to breaking point. At the slightest failure of the locomotive, we believe it’s all over. Because this engine is no better than the other.”

The other being the crashed locomotive at Bellevue.

The fireman suddenly emerges from his silence:

“We’re not cowards, sir! We’ve all driven these machines more than once. But to have to carry on in a pile of junk which is in danger of falling apart by the minute, knowing about it and having to do it anyway, is intolerable. When there is “breakage,” we’re the first victims, and if, by some miracle, we come out of it with just a broken arm or a broken shoulder, it’s off to the hospital and then maybe to jail for us.

Our deceased brother at Bellevue was the best of us. Sixteen years of service. Top marks. The pride of our line. Well, sir, that tough guy was also afraid. Yesterday, before going up the mountain, he said to us as he left the station: ‘Brothers, I’m afraid!’ He knew the locomotive wouldn’t stay on the track.

He’d reported problems more than once. But no-one cared!

How can we not be afraid when we know we may be going to our deaths?”

There was still a small miracle. If the convoy, no longer biting the rack rail and cascading down the slope, hadn’t stopped there at the foot of that mountain, rolling instead a little further, the accident would certainly have been far more horrific. There would not have been a single survivor. Everyone, without exception, would have been crushed to death. The convoy could also have plunged down to the left, over the precipice, and that would have left no survivors either.

The wreckage of the train lies in an area of over 100 metres. The locomotive? It’s now just a heap of scrap metal. Two wheels were detached under the violence of the shock. Below, in the precipice, lies the fourth-class carriage, or rather what remains of it. There, for six hours, 19 people were trapped in agony, buried under a layer of scrap iron, woodwork, stones and earth. A large tomb from which 13 corpses and six dying were eventually removed.

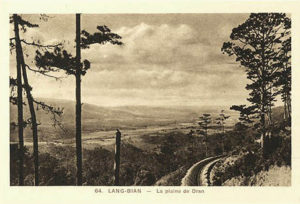

Lang-Bian – Dran plain

Suddenly, a European man with a whip, presumably a supervisor or controller of CFI, charged towards me and shouted: “Get out of here right now!”

Seeing the camera hanging under my armpit, he tore it off violently, and without saying a word, opened it, took out the strip of film, and tore it up angrily.

“No photos, do you hear? And clear off as quickly as possible!”

Such exquisite politeness.

At the scene of the last rail disaster in Da-Bac, it was the same order: Don’t allow journalists to take any photographs. Understanding perfectly why these gentlemen don’t like photos, I retreat under the wrathful gaze of this irascible railway company agent.

On the platform of Bellevue station, I catch sight of a familiar figure: that of Mr Gassier, the big boss of public works, who had travelled down from Hà Nội to contemplate the results of the accident: 17 dead and 23 dying out of 44 passengers.

The causes of the accident are known to everyone. Just three days earlier, the locomotive hauling the ill-fated train had lost its grip on the rack rail and slipped, but at a point on the line where the slope was not steep and the driver was able to stop his machine with the hand brake. The same driver – the “pride of the line” – and the same locomotive. But if this obscure hero had escaped that small accident three days ago, he was still destined for catastrophe.

The expiatory victims

In the depot at Đà Lạt, four steam behemoths are lined up side by side. One of them is still hot and out of breath. Crouching next to it, a man in blue overalls stands in a large patch of grease and oil, wielding a large oil can. On the opposite side, another man hammers heavily.

Đà Lạt, 1940s – La Gare

When we arrive, the man with the oil can looks up. The mechanic who serves as my guide greets him, then we take a little walk around the depot.

“He’s just come in after driving the up express, 300 kilometres in total. Followed by two hours of shunting in the station. Tonight, he’ll drive the down express. Another 300 kilometres and then more shunting in the station.”

I’m stunned.

“And now he has to maintain his machine too? So when will he get some rest?”

My companion shrugs his shoulders,

“He can always rest for an hour or two if his ‘beast’ doesn’t give him too much trouble. Otherwise, he’ll rest tomorrow, after he’s finished taking the down express and done his shunting at the station.

For us, you know, rest, Sundays, holidays, official days off, are all just ideas on paper. We get just four days off per month, and that’s if no colleague gets sick unexpectedly. In the event that one of us gets sick, he must be replaced. So those four days can be reduced to just two.

But let me go and give my colleagues a hand.”

While my companion goes to assist his two comrades, I observe them. All of them have ravaged faces. And they’re all between 25 and 35, that is, all in their prime.

I understand now why they age so early.

They’re now finished. At the station buffet, they throw themselves heavily into the ugly armchairs, wiping large drops the sweat from their brows with the backs of their hands. I offer them a drink.

Both the driver and fireman refuse.

“Well, if you want, you can eat something with us, we haven’t eaten yet.”

Đà Lạt, 1940s – Gare intérieur

Smiling, my companion said to me:

“You could be the unintentional perpetrator of a disaster by offering them something a drink. For us, no alcohol!

But the temptation’s very strong, you know! After 300 kilometres standing on the footplate of our ‘beasts,’ eyes wide open, ears constantly on the alert, we’re running on empty! And with the prospect of having to provide the same amount of exhausting effort that same evening or the next day at the latest, you’ll understand that there’s a strong temptation to pull oneself together with a stiff drink. But woe to anyone who succumbs!” Both the driver and the fireman nod in agreement.

“Already the authorities all too often pour all the fault for any problems onto our heads. We are the expiatory victims, sacrificed to public opinion by our leaders whenever a catastrophe occurs, whether we’re dead or still alive. Whether it’s the Đồng Hới accident or the Da Bac accident or the recent one in Đà Lạt, we’re always the people responsible! No-one ever talks about worn equipment, or poorly made track. Because if there were any question of that, the bigwigs would also have to accept their share of responsibility.”

I try to console them: “Public opinion is not always wrong. For the Diêu Trì accident, for example, the courts sentenced the locomotive driver to one year in prison. But he was then granted a suspended sentence. For public opinion, this was equivalent to condemnation of the senior officials, who they could not dare to drag into the box with the accused.”

But they continue. “Even where we must admit that we caused a catastrophe, who are the real culprits? Ask our masters if they would drive 600 kilometres there and back in less than two days, standing in front of a scorching firebox and constantly staring into the night, not to mention all that exhausting shunting work at the station. Could they do this work? Human resistance has limits.”

Unidentified SLM HG4/4 0-8-0T cog locomotive in the Bellevue Pass

Then, after a short pause to calm his indignation:

“I’ll tell you a little story from last year. Once, when my turn came, my eyes hurt. I protested to the chief traction engineer that working in my state would expose passengers to certain disaster. Because everything depends on the power and the visibility of our eyes. But no matter how much I protested, he didn’t give a damn. So I had to harness my “beast” to the express. For the first 100 kilometres, by some superhuman effort, I managed to drive properly.

But then suddenly my eyes became clouded. I couldn’t see anything. I was blinded, and furthermore lost consciousness. The train was about a kilometre from a tunnel preceded by a steep ramp. Catastrophe was certain.

And at first the fireman and the trainee driver who was travelling with us didn’t notice a thing! But then, fortunately, he saw me collapse and caught me as I fell, while the trainee grabbed the brake. This allowed us to slow down when we got to the ramp. Needless to say, for the rest of the journey, the trainee was driving with the fireman’s help.”

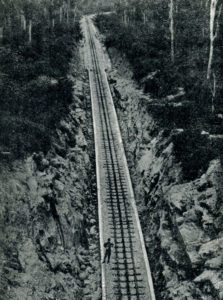

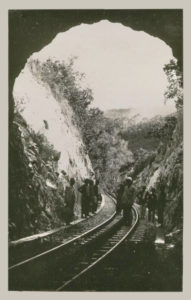

“Ligne de Krongpha à Dalat – chantiers à Bellevue,” janvier 1931 – “Krongpha-Dalat line – works at Bellevue,” January 1931

His companion smiles:

“That fireman was me. It’s fortunate that on that day, or rather that night, we had a trainee by our side, and one who knew the machines better than I did!”

“So there aren’t always trainees on the locomotives?”

“The presence of driver, fireman and trainee is exceptional. The ongoing shortage of traction personnel is such that these apprentices often have to drive by themselves – sometimes even an express. During the terrible accident in Đồng Hới, it was a trainee who was driving!”

“And today?”

“Nothing’s changed. Today is like yesterday and tomorrow will be like today. There are always trainees driving. It would be understandable if we cost too much, but a fireman earns only 35 piastres and a driver 40 piastres a month. Get rid of just one of those numerous engineers who work in management, and we could recruit a dozen more firemen and drivers …”

I can’t help but shudder. Here, I believe, is one of the main causes of so many railway catastrophes!

On the downward journey the train stops suddenly and hisses for a long time. A station? But I didn’t hear the usual whistle that announces scheduled stops It must be a breakdown. How long will it last?

I clamber out of my carriage and walk forward along the track. We overlook a steep precipice of the kind we often see on the Huè-Tourane route and around the Cap Varella. The locomotive is slipping on the track and can’t climb. Discussion between the fireman and the guard. They ask for some volunteers to slide grit under the wheels. A group of good-natured passengers lend themselves to this little task, which amuses them at first, but which, in the long run, becomes tedious.

Eventually they can move the locomotive forward. Slowly. Soon afterwards, we encounter the same problem again! After a quarter of an hour, again with the help of the passengers, the train can creep up the slope. Now it’s going down again. For the descent, we can be confident. It knows how to freewheel. We just hope the brakes are working well!

The problems

The fireman’s incredible admission. The report to the Grand Council of Economic and Financial Interests in 1936 has since been irrefutably confirmed: The rolling stock is “at the limit of its resistance.” And these disasters are not yet at an end. The Đồng Hới accident which prompted this admission was just the start, and the recent Kabeu accident will not be the last. The abyss is the abyss, catastrophes are catastrophes.

The problem needs to be studied again.

We asked a specialist his opinion in order to close this investigation. This is what he told us:

“The two main issues to be studied are: track and traction.

Track

“Cochinchine – Environs de Saïgon, 1904 – Passage à niveau sur la voie ferrée,” Fonds Breton “Cochinchine – Outside Saïgon, 1904 – Level crossing on the railway line,” Fonds Breton

“The cost of building the Réseaux non concédés [CFI] totalled 2,665 million 1928 gold francs, or roughly 5,400 million Daladier francs. The cost per kilometre was roughly 2 million francs, double the average cost in France, 1.9 times that in Algeria, and 1.5 times that in Tunisia. Yet it was the most poorly constructed of all. Some lines already need completely rebuilding!

First, the cardinal crime. Indochina was underestimated by giving it a track gauge of only 1m instead of the international gauge of 1.435m. The 1m gauge track is fine for ‘lines of penetration’ such as those from Hải Phòng to Yunnan-fu, from Blida to Djelfa (Algeria), etc … with a continuous ramp over several dozen kilometres and minimum slopes of 18mm/m. On such lines, 1m gauge track significantly reduces the cost of earthworks, and is faster and more economical to install.

However, the Transindochinois was not a ‘line of penetration,’ and it was also not very difficult to construct. Only the ineptitude of some engineers made construction so difficult. The hardest sections to build were those of the Col des Nuages and the Cap Varella. However, the altitude in those places is only 400m to 600m, with maximum gradients of just 15mm/m.

The 1m gauge track offers much less safety than that of l.435m. The multiple accidents which bloodied the last semester of 1938 came about partly because of this original design error.

The preliminary studies were also very poorly carried out. A track of only 1m gauge should have very few sharp curves, as few as possible. However, I was able to identify on the Transindochinois alone at least 50 sharp curves which needed to be corrected.”

“These already ill-conceived railway lines were then constructed very poorly. It’s no secret that, thanks to the complicity or ignorance of certain engineers of the Public Works Department, contractors involved in building the line were not properly supervised and gave poor results.

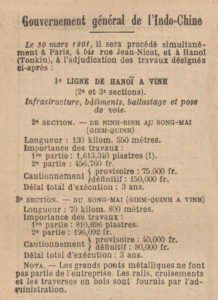

“La ligne de Hanoi a Vinh,” Journal officiel de la République française. Lois et décrets, 20 Janvier 1901 – Call for tenders

For the Vinh-Đông Hà section, for example, during the first year of operation of the line alone, around 20 bridges had to be repaired, and earthworks had to be re-consolidated over about 50km of track. Additional cost: 77 million francs (Poincaré francs).”

“The safety of the track is further impaired by the use of lightweight rails of 25kg instead of those of 30kg commonly used on all foreign railway lines, and the use of iron instead of ‘lim’ wood for the sleepers (ties). The multiple drawbacks of iron sleepers (excessive expansion and contraction, poor adhesion to ballast, etc) have been pointed out on several occasions. Yet, despite the abundance of ‘lim’ wood in the country, despite its relative cheapness, despite its advantages in adhesion, we continue to buy iron sleepers.

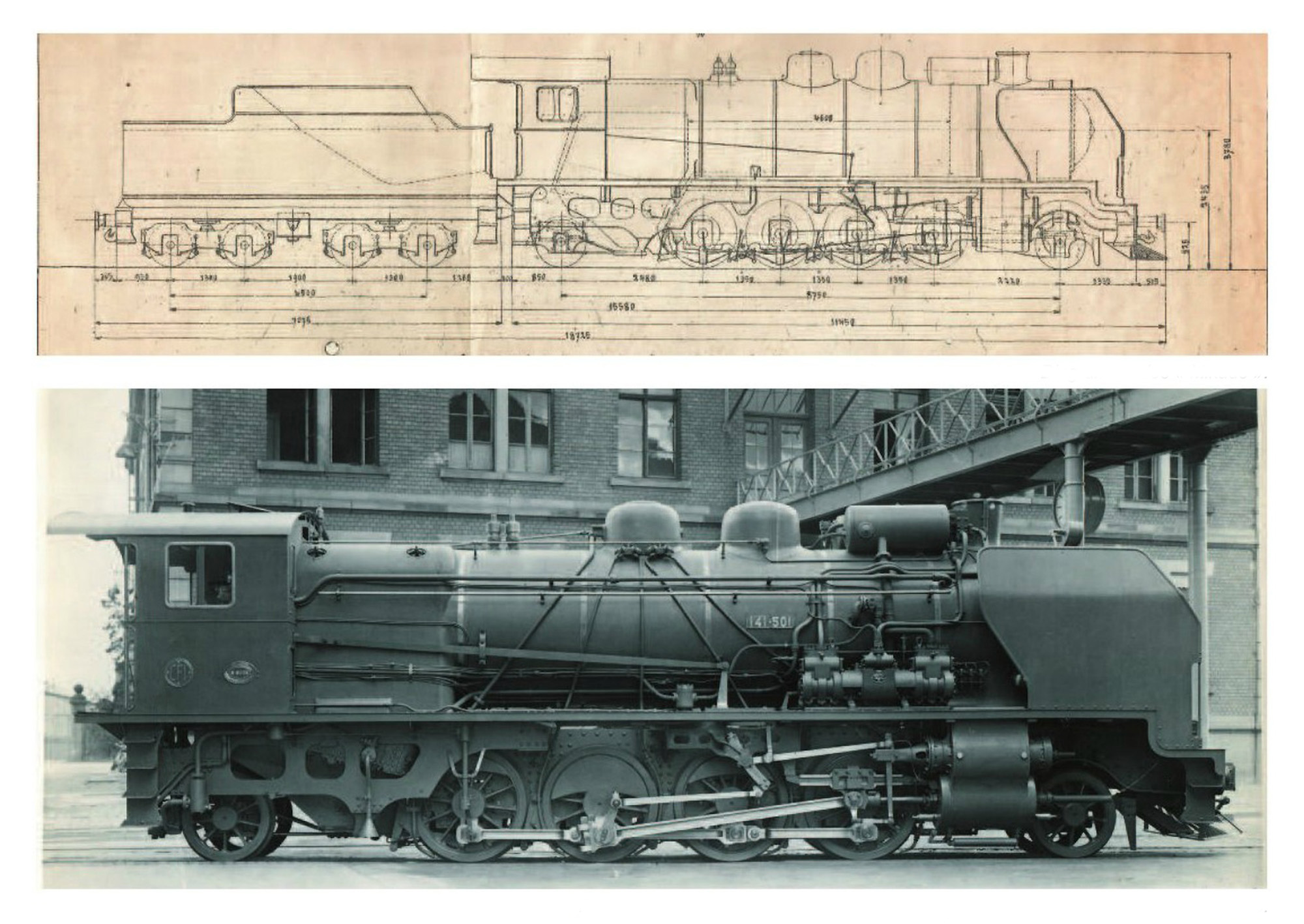

Traction

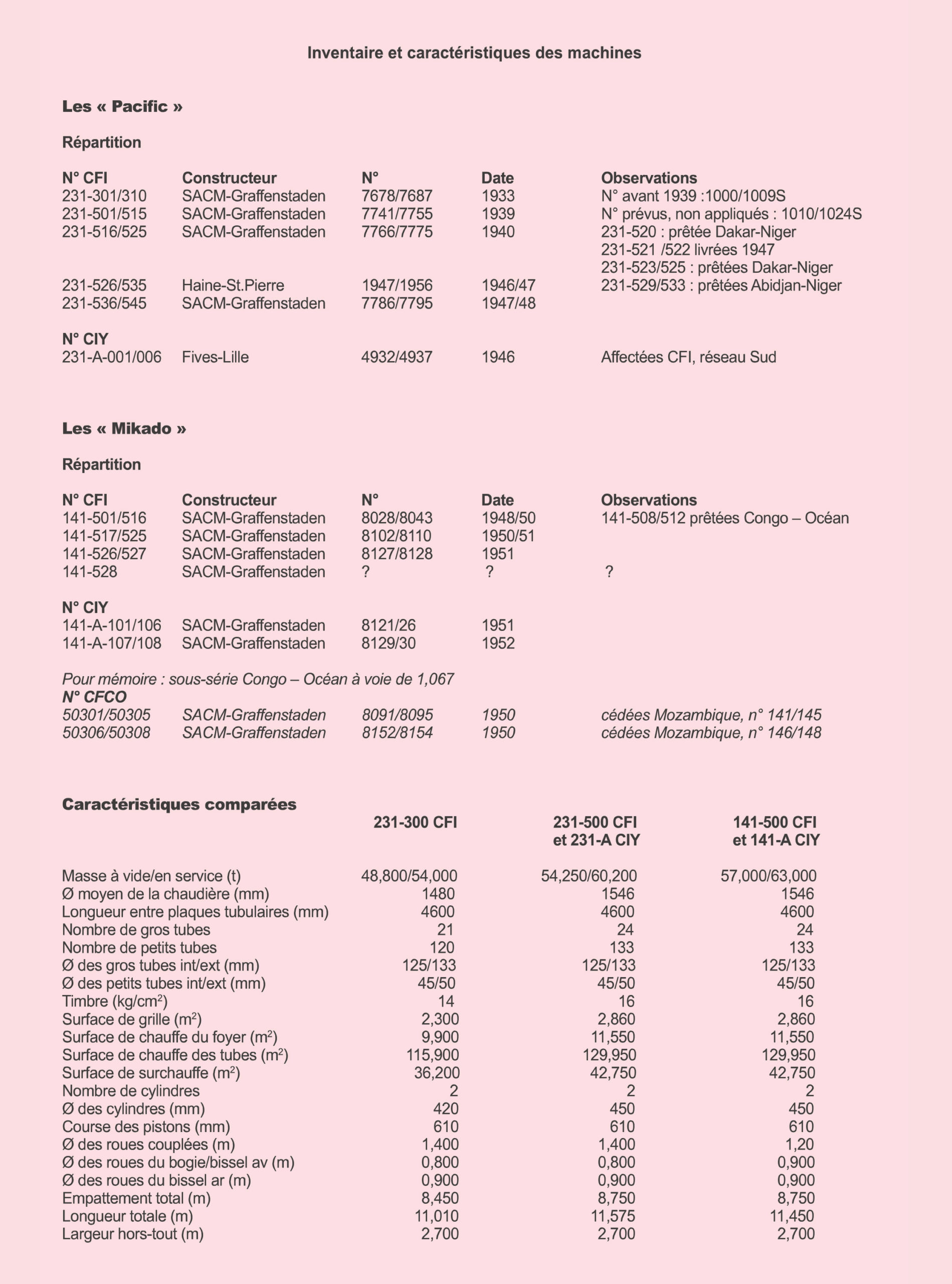

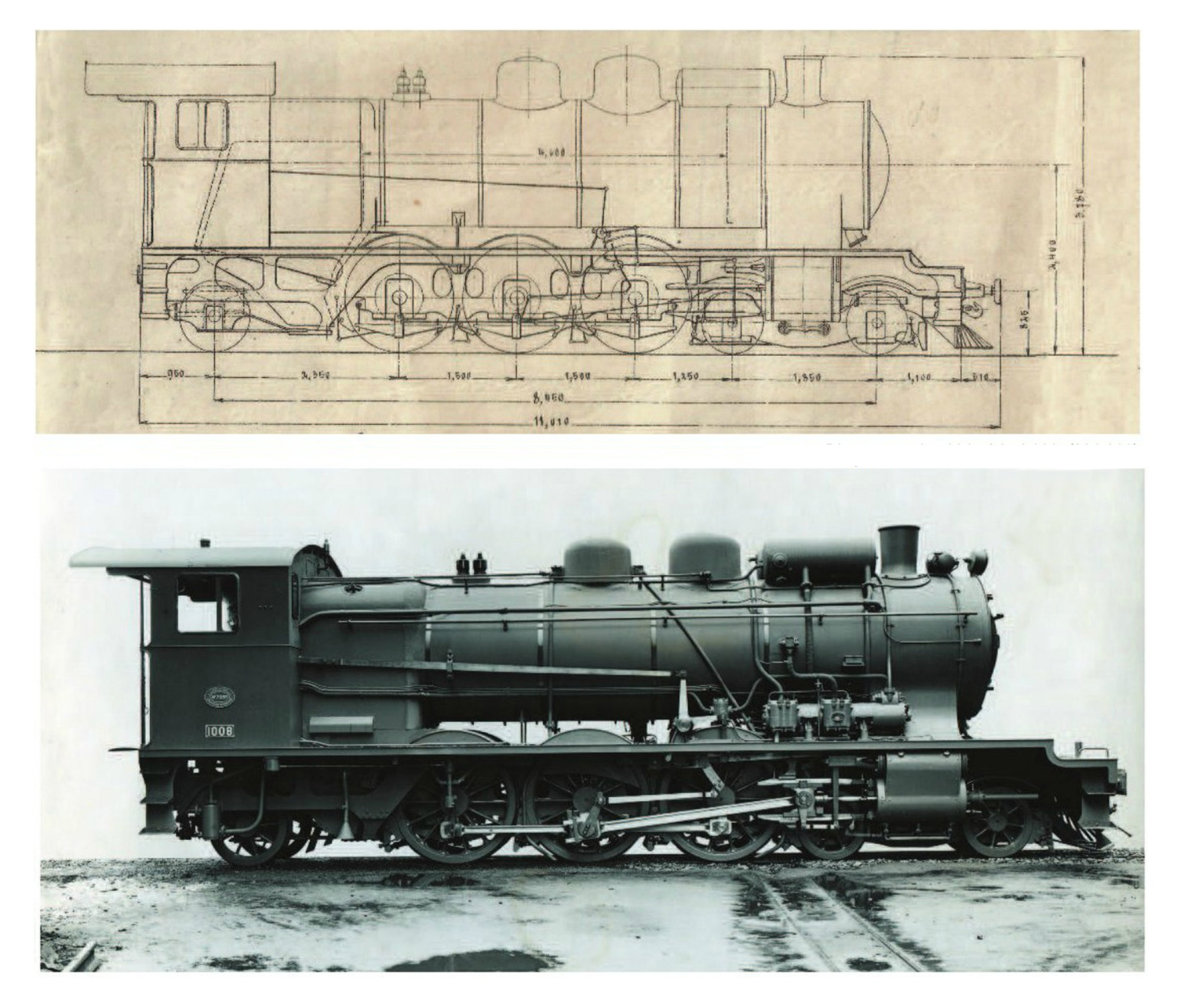

“Of the approximately 260 locomotives in service on the Réseaux non concédés [CFI], only about 30 are of recent construction. These are the type 300 “Ten-wheels” and 1000 “Pacifics,” which operate the daily fast-track Hà Nội-Saigon services. And they are only capable of hauling 170 tons on the steepest slopes of the Transindochinois such as the Col des Nuages. The rest of the fleet is junk which is between 20 and 40 years old.

But on the Indochina railways, with its fairly steep ramps, very steep curves, and often fanciful layout, the problem of traction is of paramount importance.

The axle load is, as we know, a crucial factor – the grip of a locomotive depends on its axle load, the pressure pushing its driving wheels onto the track. However, our track and other structures are so fragile that the axle load, that is to say the grip of the wheels on the rails, must be kept to a minimum.

Grip also depends on the number of driving wheels. The more wheels there are, the better the grip.

Hence the need to make the locomotive heavier, at the same time as distributing the weight between the greatest number of wheels. But this multiplication of driving wheels lengthens the locomotive, which in turn presents risks when it enters a sharp bend. Hence the need to articulate the locomotive.

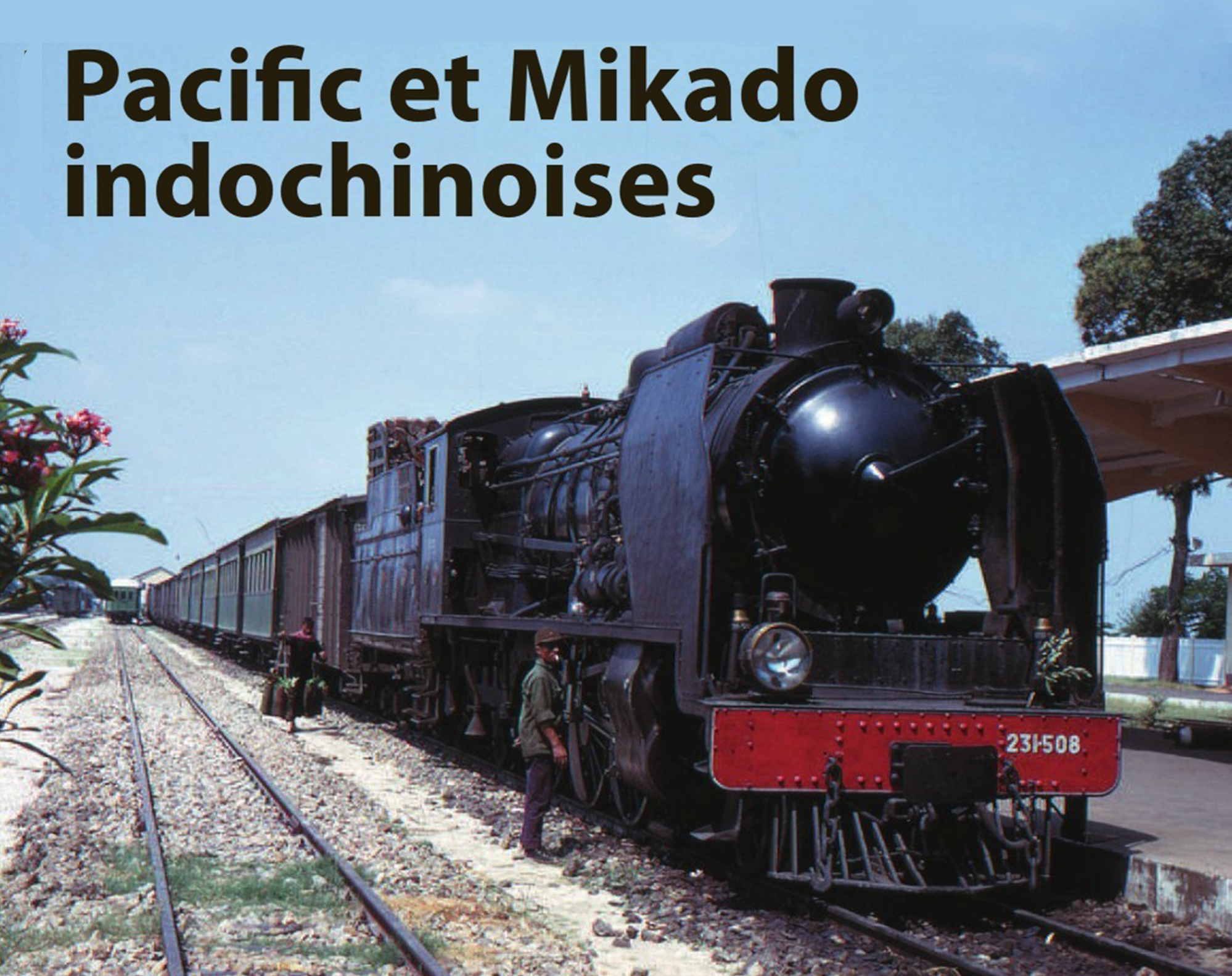

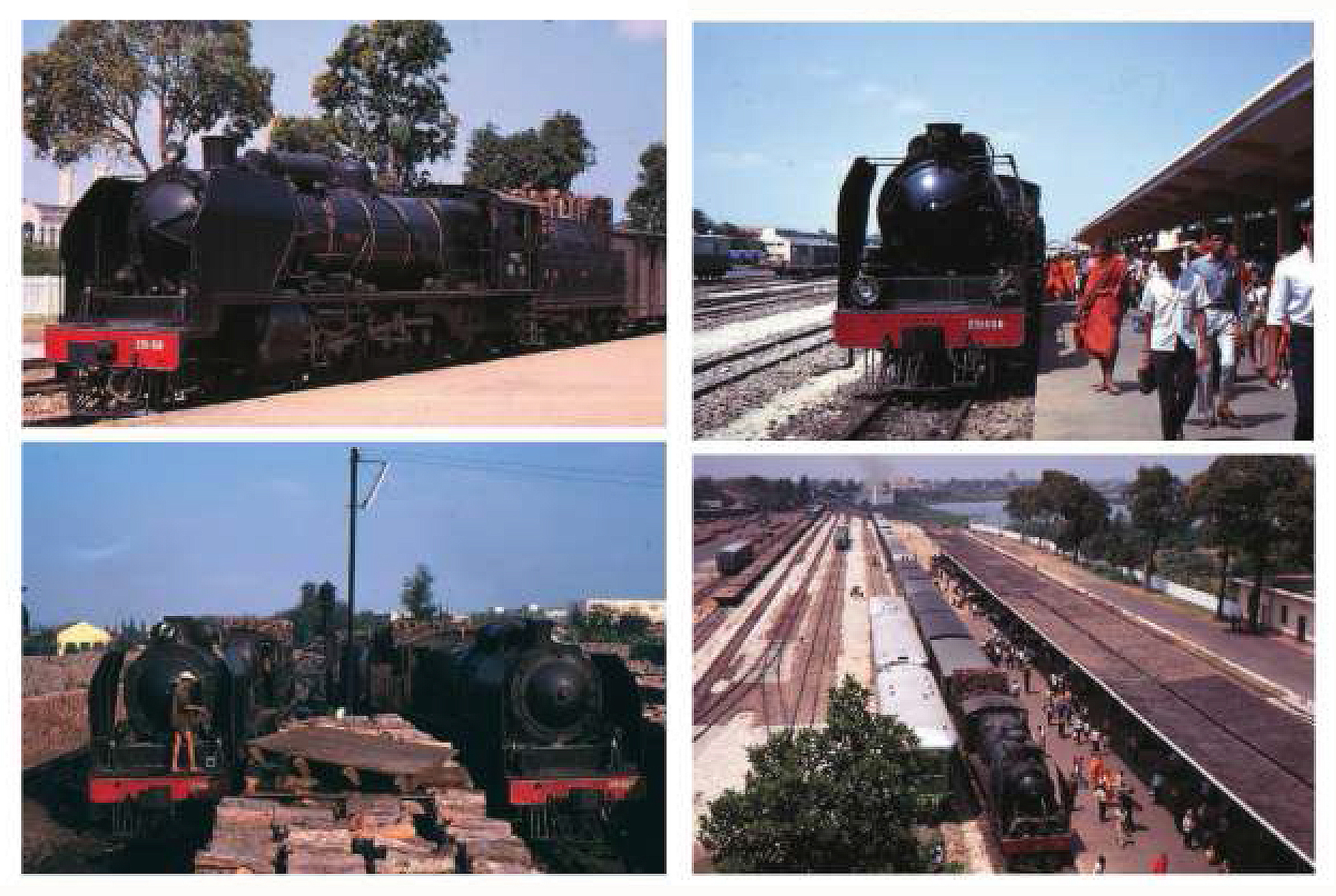

SACM “Pacific” No 1004, decked out for the completion of the Transindochinois in October 1936. Photo Sarthe/Collection José Banaudo

The type of locomotive which would best meet the peculiarities of the Indochina railways is the ‘Garratt’ type, a locomotive with a 4-8-2+2-8-4 ‘Double Mountain’ type wheel arrangement, 23m long and articulated into three sections, which is already widely used on more than 70 networks in Africa and in particular in Algeria.

Such a machine is built especially for the colonial networks, that is to say for 1m gauge track. It can haul not only heavy convoys of goods, but also passenger trains at a speeds reaching 100km per hour.

It can make sharp curves of up to 120m radius and carry 12,000kg of coal and 28 cubic meters of water. It’s worth more than two standard locomotives put together: 23% savings in deadweight and an increase in traction power of 38%. It can cover great distances without refuelling, which saves time and makes real savings in operating costs.

This type of machine is fitted with the latest modern improvements: four cylinders, superheating, powerful braking including a compressed air emergency braking system, lighting in the cabin and front and rear headlights.

For shorter trips, the current pile of scrap would need to be replaced by light and fast diesel-electric locomotives, in which a diesel engine drives a group of electric generators.

An 8-cylinder four-stroke diesel develops a continuous power of 920hp at 700 rpm, the electric generator controls three traction motors which are connected to the machine’s three driving axles. In running order, one type, which measures 15.13m in length and weighs 100 tonnes, can haul a 90-tonne train at more than 100km per hour for a journey of about 1,400 kilometres without refuelling. While diesel-electric locomotives have the disadvantage of high weight compared to unit horsepower, on the other hand, they consume diesel oil, which is said to be cheaper than coal.

Of course, if we replace the locomotives, we also have to replace the wagons, or at least strengthen them.”

Too many chiefs and too few workers

Annam, Tuy-Hòa – 230 “Ten-wheel” No 316 stops at Tuy-Hòa, Document Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer

Let’s take a look at the budget for the Réseaux non concédés [CFI]. We see in the chapter of expenditure just 373,680 piastres for maintenance, repairs and works, 3,129,900 piastres for rolling stock and 4,025,490 piastres for personnel. The staff of the Réseaux non concédés breaks down as follows: 9,556 locals and 180 Europeans. The 9,556 local employees receive only 2,883,090 piastres, while the 180 European staff earn up to 1,142,400 piastres, that is, an average of 630 piastres per month for each European and an average of 302 piastres per year for each local employee.

Now let’s look at the operating expenses by category since 1932.

While the expenses for personnel fell from 1,819,000 piastres in 1932 to 1,263,000 piastres in 1936 for the Northern Network and from 1,115,000 piastres to 773,000 piastres for the Southern Network, the expenses of the Operations Department increased from 59,000 piastres in 1932 to 162,000 piastres in 1935 and 180,000 piastres in 1936.

“There are too many chiefs!” said a railwayman of my acquaintance. Yes, there really are too many chiefs, and they cost too much. For each Arrondissement in the CFI Directorate there is a Principal Engineer assisted by an Engineer Office Chief and three Deputies, one for Traffic and Movement, another for Track and Buildings and a third for Traction. Each of these Deputies in turn have three Assistants, all engineers who each cost the budget over 400 piastres a month.

On the other hand, lower-grade staff are clearly insufficient. And very poorly paid.

In Traffic, a man working in a team gets 14 piastres per month, a handling manager 18 piastres, a brigadier 30 piastres and a team leader 35 piastres. In Movement, a station postman earns 21 piastres, a substitute station postman 29 piastres, a station master 4 35 piastres and a temporary worker 2 45 piastres. The privileged ones, station masters of major city stations, earn just 60 piastres. For the train service, a guard earns 15 piastres, a student conductor 21 piastres. a chef de train 30 piastres and a route controller 45 piastres. In Traction, a trainee earns 21 piastres. a fireman 35 piastres and a driver 40 piastres.

Annam – Krôngpha, c 1935 – Tourcham-Đà Lạt railway line, photo Raymond Chagneau

In return, what a lot of work! I will never be able to forget the words of the mechanic in Đà Lạt: “”For us, you know, rest, Sundays, holidays, official days off, are just ideas on paper.”

An eight-hour day for the telegraph operator who must focus from morning until night on his telegraph machine.

An eight-hour day for the station master who at nighttime must still interrupt his sleep at the sound of the telegraph machine to answer or forward telegrams, to attend the arrival and departure of every express, to update his registers, and to read the tedious circulars which the chiefs throw at him day after day.

What about the 40-hour week? Is the week really just 40 hours for conductors and road inspectors for whom there are no Sundays or public holidays, employees who only have two days off per fortnight? And those two days of rest are often reduced to just one. Because the staff shortage is such that one should expect at any time to be brought in to replace a failing comrade.

And then there’s the conduct of the chiefs, of certain chiefs, of course! Not so long ago, an engineer was witnessed hissing and pouring insults on his subordinates! In important stations, postmen, crew members, etc, are at the same time under the orders of the group leader, the controller, the station master and the deputy station master. Four leaders, four gods who are always angry, who, at the slightest mistake, can issue a written reprimand. However, four reprimands per month result in demotion by one grade. In this way, a station postman was demoted for having received four reprimands in a month: his “crimes” included wearing clogs while selling tickets, forgetting to greet the controller who was on the train platform and whom he had not seen, and smoking when the engineer (who hates tobacco) walked past him!

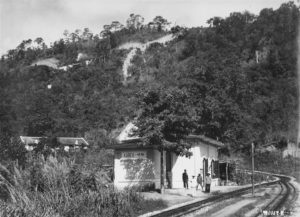

Gare de Kabeu, 1930

A station master was also sacked when, with a train waiting in the station, he returned to his room at the calls of his wife, who was being assaulted by a controller!

In this service, where one is under the orders of five fathers and three mothers (năm cha ba mẹ), such cases of injustice are common.

The Đà Lạt accident is simply the last straw which has overflowed the already full cup of public outrage.

Across the country there is a huge cry of anger. Let Governor-General Brévié know this and take the necessary reforms without hesitation!

Xuân Tiếu

POST SCRIPTUM: RECIEPTS FROM THE RAILWAYS

The receipts of the railway lines operated by the colony for the first quarter of 1938 reached 819,449 piastres against 521,075 piastres for the same period of 1937, that is to say an increase of 43,107. All the lines contribute to this increase, with the exception of the Saigon-Bến Đồng Sổ section of the Lộc Ninh line, which shows a loss of 766 piastres.

It should be noted that, of these 43,107 increases in revenue, 20,000 may be accounted for by increases in tariffs decided at the last annual session of the Grand Council of Economic and Financial Interests of Indochina.

The remainder, or 23,107, represents the share of the acceleration of business and economic recovery.

The railway management did not find it useful to specify whether this is gross or net revenue. We believe that these figures represent gross receipts, that is to say without deducting ordinary expenses (personnel, maintenance of equipment etc…) and extraordinary expenses (repair and replacement of locomotives and other rolling stock destroyed in the recent disasters).

For the Réseaux concédés [CIY] from Haiphong to Yunnan-Fu. receipts during the first half of 1938 amounted to 2,381,396 piastres, an increase of 79.50%.

The per kilometre revenue on the CIY line is almost 320% of that of the state network.

Another reason which militates in favour of a radical reorganisation of our railways.

Tim Doling is the author of The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, 2012) and the guidebooks Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018), Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019) and Exploring Quảng Nam (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2020).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.