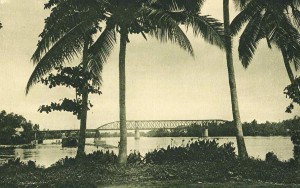

The restored “Rainbow Bridge” (formerly the Pont des Messageries maritimes) today

This article was previously published in Saigoneer http://saigoneer.com/

Many people will be familiar with the spurious claims that French civil engineer and architect Gustave Eiffel (1832-1923) was responsible for three of Việt Nam’s most iconic structures, the Long Biên Bridge (Pont Doumer) in Hà Nội , the Trường Tiền Bridge in Huế and the Saigon Post Office. The prevalence of such claims makes it all the more strange that so few visitors to Saigon are given the chance to visit the “Rainbow Bridge,” formerly the Pont des Messageries maritimes, which in truth is Eiffel’s only major surviving work in Việt Nam.

Gustav Eiffel

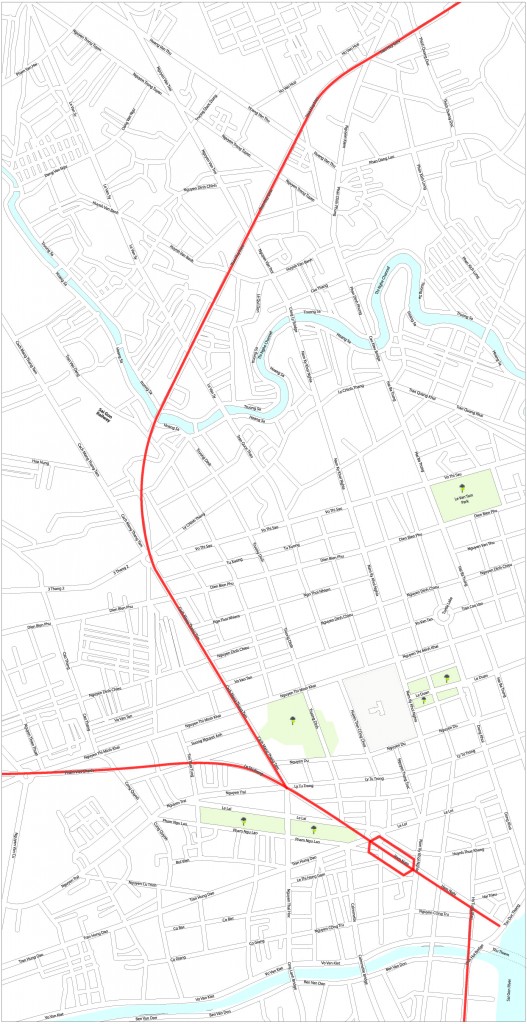

In 1872, recognising that there was serious money to be made from the flurry of infrastructural projects then getting underway in the new French colony of Cochinchine, Gustave Eiffel opened an office on Saïgon’s rue Mac-Mahon, now Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa street. In subsequent years his company made a name for itself by constructing canal bridges all over the Mekong Delta.

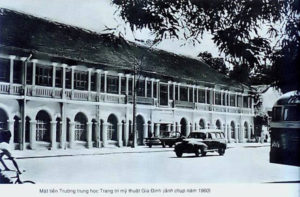

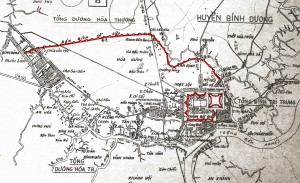

Starting in the early 1880s, the colonial authorities began to build railways and tramways in order to enhance lines of communication and provide investment opportunities for French capitalists. After a shaky start building the defective Bình Điền, Tân An and Bến Lức viaducts for the Sài Gòn–Mỹ Tho line (opened 1885), the newly-renamed Compagnie des Établissements Eiffel soon emerged as the leading manufacturer of metal-framed structures.

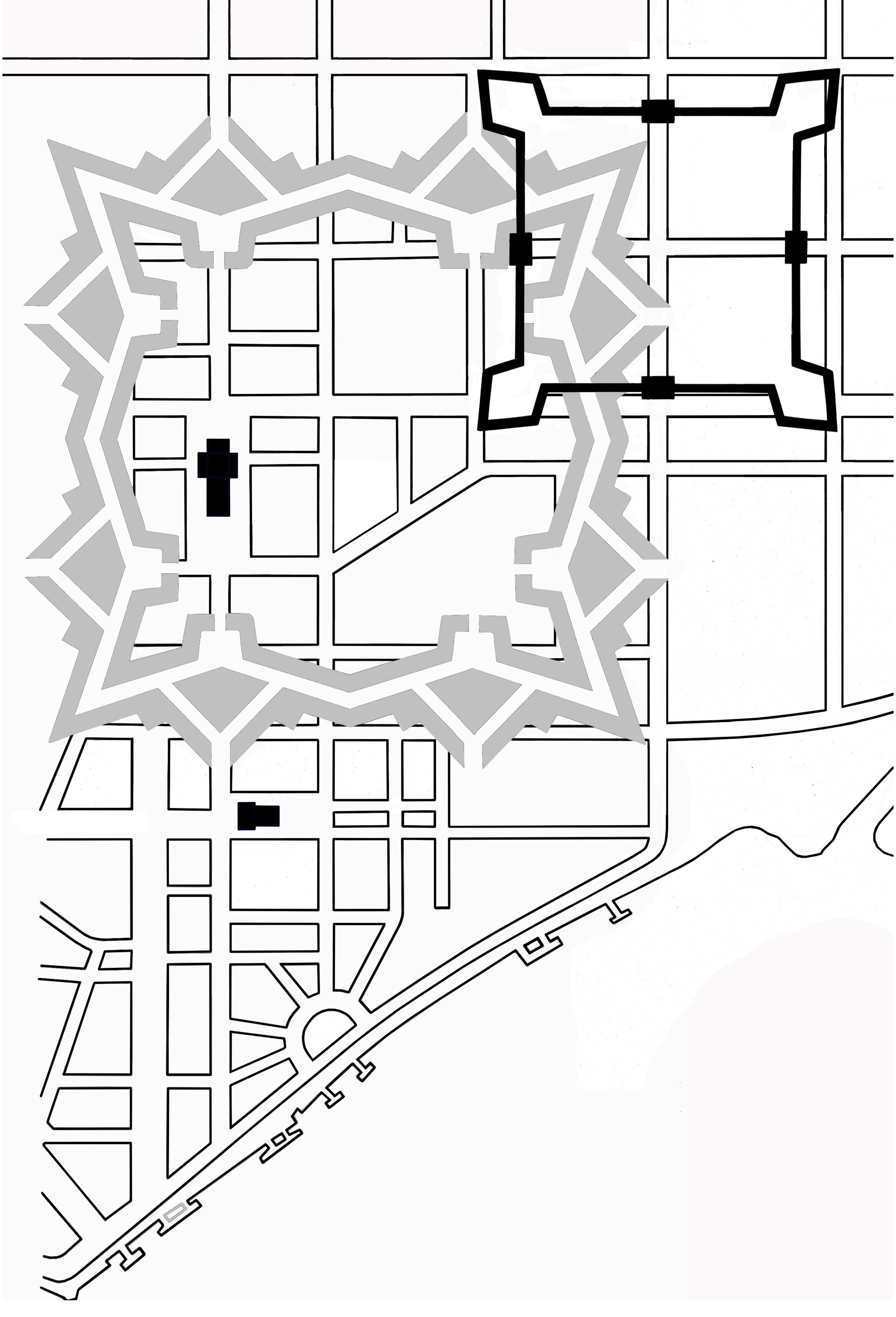

Eiffel’s Tân An viaduct on the former Sài Gòn–Mỹ Tho railway line

Most of the company’s work was focused on the south, where it was engaged to build a wide variety of structures, ranging from the markets at Cao Lãnh (1887), Ô Môn (1888), Tân Quy Đông (1889) and Tân An (1889) in the Mekong Delta to the imposing Halles des Messageries fluviales building on the Saïgon riverfront.

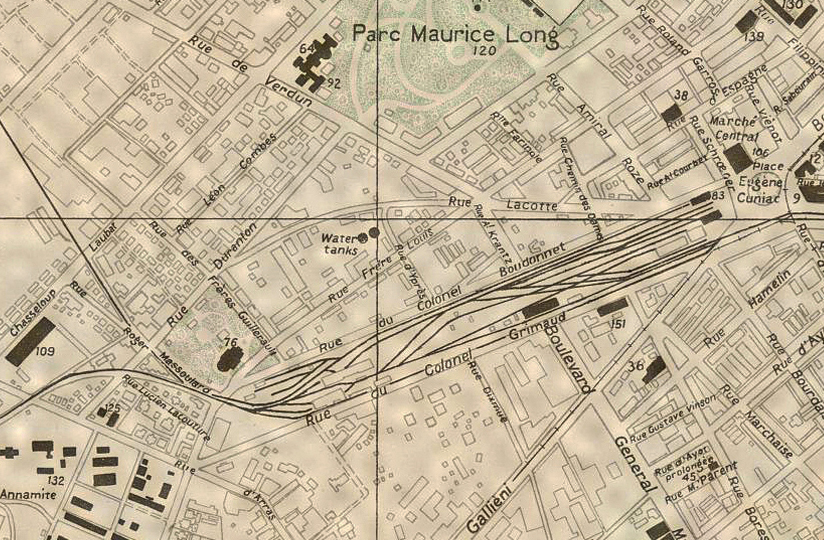

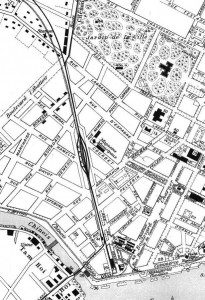

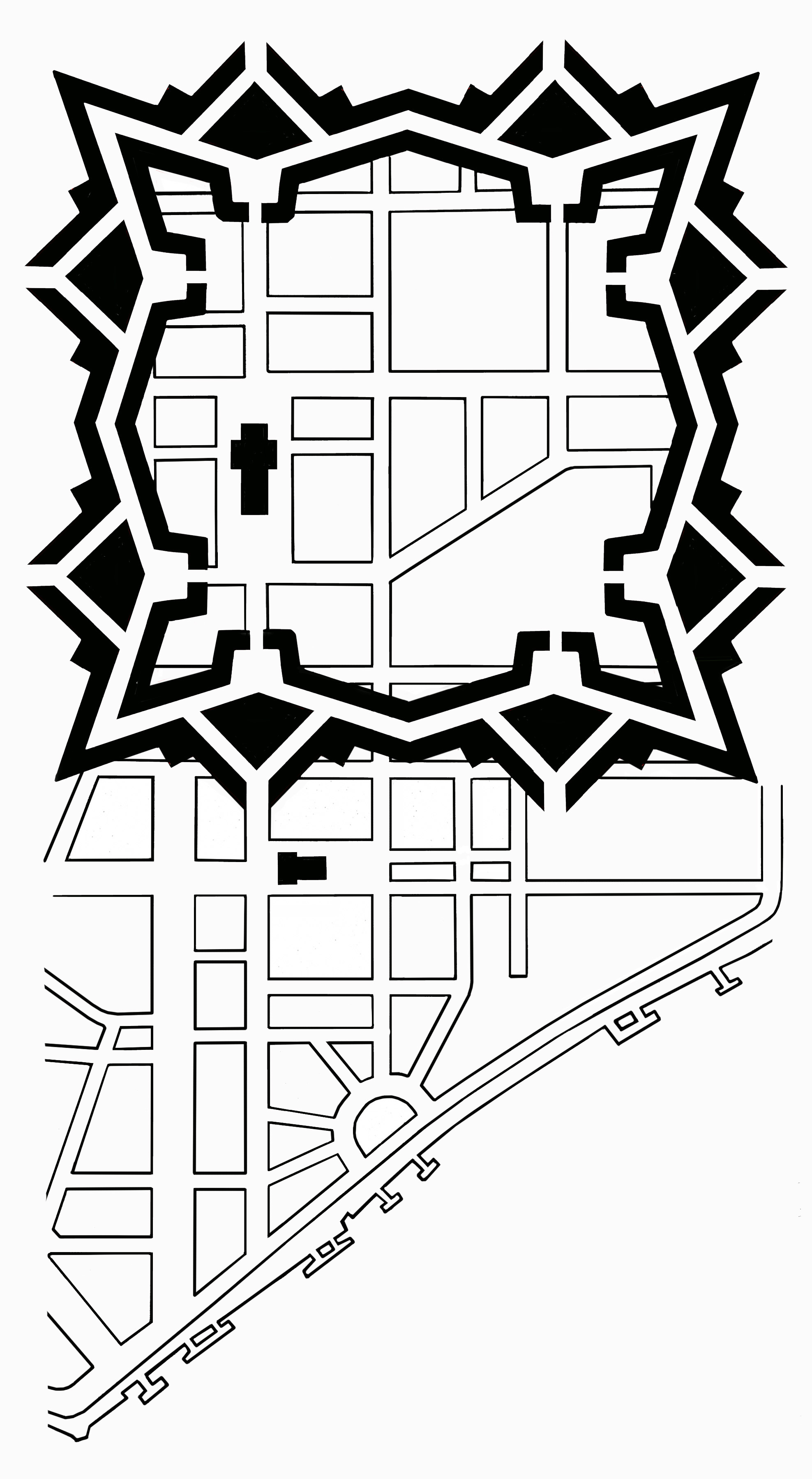

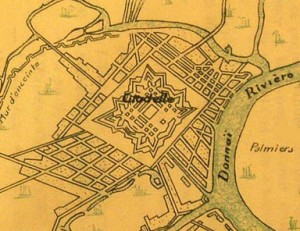

In 1881-1882, the Établissements Eiffel built the Pont des Messageries maritimes (also known as the Pont de Khanh-Hoi) over the Arroyo Chinois (Bến Nghé Creek) to connect the ville basse or lower town with the headquarters of the Compagnie des messageries maritimes in Khánh Hội. Two years later, they built an almost identical bridge named the Pont des Malabars in Chợ Lớn, to connect that city with what is now District 8.

The Pont des Messageries maritimes in the late 19th century

Unfortunately, the Pont des Malabars was demolished in the 1930s, but its sister bridge, the Pont des Messageries maritimes, has survived, and was sympathetically refurbished in 2010 as part of a landscaping project which transformed it from a road bridge into a footbridge. Known in Vietnamese as the Cầu Mống (“Rainbow Bridge”), the 371m structure with its single wrought-iron arch and colonial lamp fittings has recently been discovered by wedding photographers and is now a popular local beauty spot.

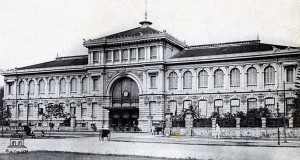

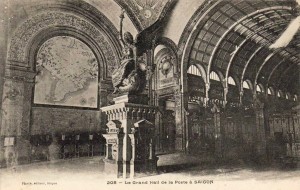

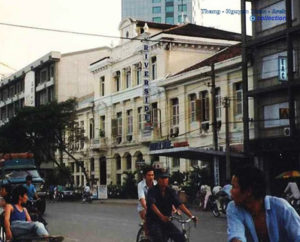

If few visitors have heard the Pont des Messageries maritimes, then even fewer people will be aware that until very recently, a second Eiffel work – the Halles des Messageries fluviales – also survived in Saigon. Built in 1899 as the headquarters of the Compagnie des messageries fluviales (River Shipping Company), it became the headquarters of the Saigon Bank for Industry and Trade (Sài Gòn Công Thương Ngân Hàng) at 18-20 Tôn Đức Thắng after 1975, but was converted into the Riverside Hotel in the late 1980s. Sadly, the hotel management was permitted to remodel its façade in the late 1990s, thereby destroying much of the original Eiffel building.

Saigon – The Riverside Hotel pictured in 1992 (photographer unknown) when it still occupied the original, unmodified Messageries fluviales headquarters building

Seven years after the Pont des Messageries maritimes opened to traffic, Eiffel built his world-famous Eiffel Tower for the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris. However, in 1893 he was forced to retire in disgrace, implicated in the financial and political scandal which surrounded the failed French project to build a canal across the Panama Isthmus.

Nonetheless, working under the new name Société Constructions Levallois-Perret, Eiffel’s old company continued to play an important role in the development of the French colony, building much of Saïgon’s port infrastructure as well as a large number of the bridges on the North-South (Transindochinois) railway line. In 1937, confident that the Panama scandal could no longer dent its founder’s reputation, the company changed its name to Anciens Établissements Eiffel.

A few later Levallois-Perret relics, such as the remains of the newly-dismantled Bình Lợi Bridge, may still be seen today in Saigon, but those in search of an authentic pre-1893 Eiffel monument in Việt Nam need look no further than the Bến Nghé Creek to admire the great man’s handiwork.

The view today from District 4 where the “Rainbow Bridge” spans the Bến Nghé Creek

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.