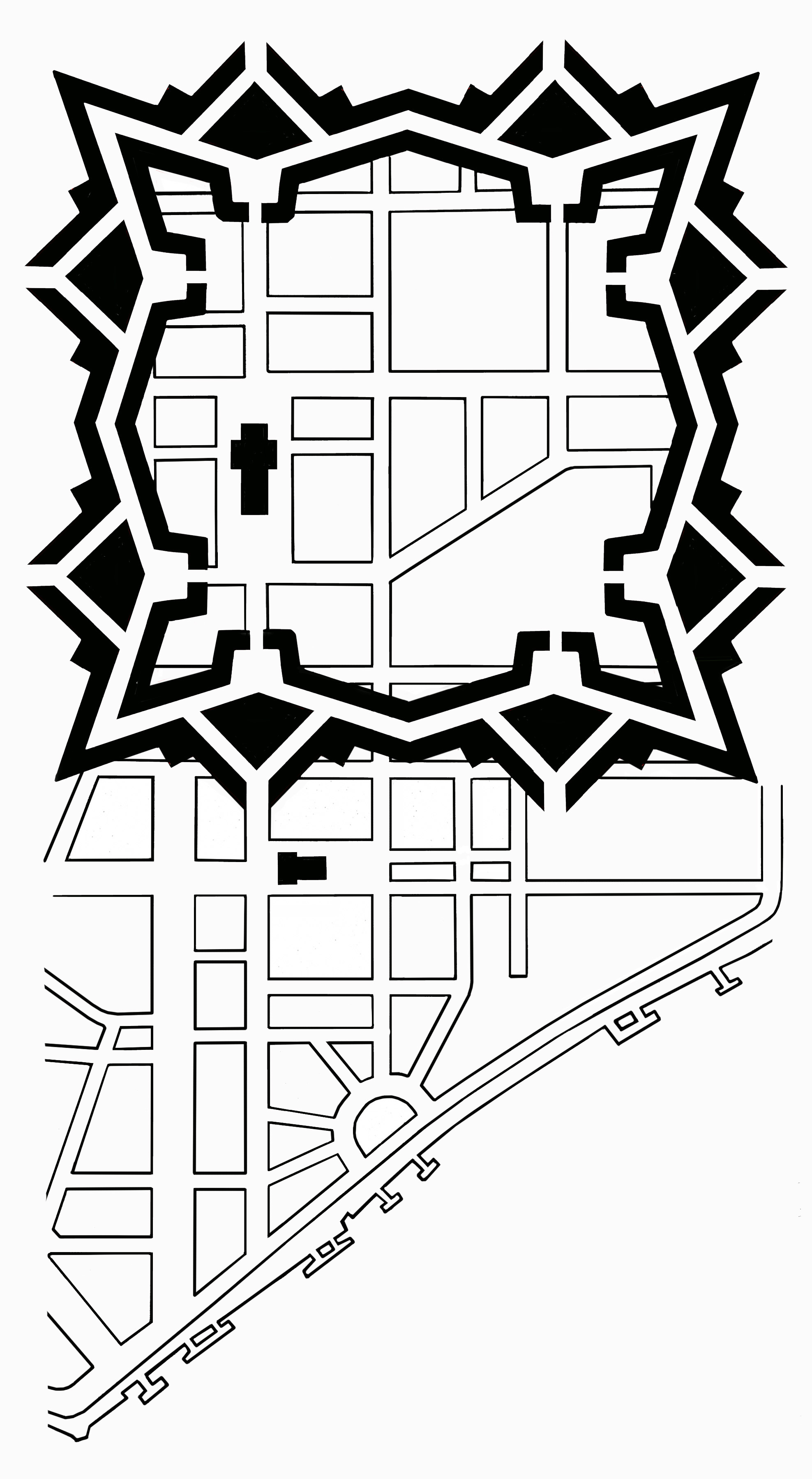

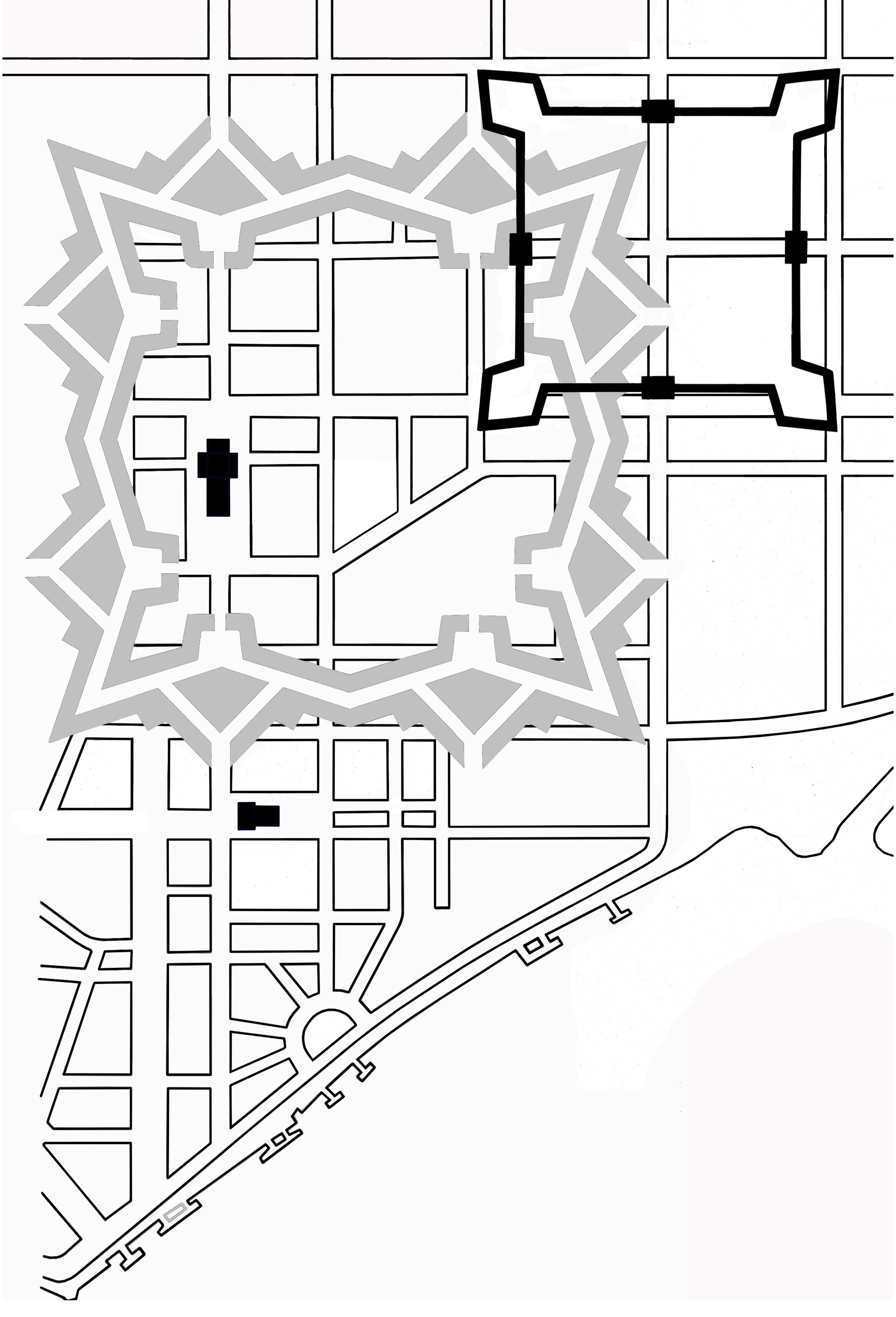

The location of the first Gia Định Citadel of 1790, superimposed on the modern street map

Tourist guidebooks often remind us that Sài Gòn once had its own citadel. In fact, within the relatively short space of 70 years (1770-1840), this city saw the construction of three major fortifications by the ruling Nguyễn family.

The earliest of these was the Lũy Bán Bích (or Bán Bích Cổ Lũy), built in 1772 by one of Lord Nguyễn Phúc Thuần’s generals, Nguyễn Cửu Đàm, to protect the settlement from invading Siamese armies.

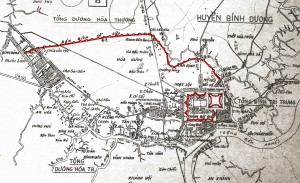

The location of the Lũy Bán Bích city walls of 1772

The Lũy Bán Bích was not a citadel but a fortified city wall, which stretched over 8.5km from the Bình Dương River in the Minh Hương settlement (Chợ Lớn) to the Thị Nghè creek in Bến Nghé (Sài Gòn). Though no traces of this structure have survived, it left a footprint in the configuration of several modern streets, including Lý Chính Thắng and Trần Quang Khải.

In his 30-year war against the Tây Sơn brothers, Nguyễn Phúc Thuần’s nephew Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh turned first to Siam and later to France for military assistance. Thanks to funds raised in the late 1780s by his French ally Pierre Pigneau de Béhaine (1741-1799), Bishop of Adran, he was able to modernise his armed forces and to engage the services of French military advisers to train them in the latest techniques of European warfare.

Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, later King Gia Long (1802-1820)

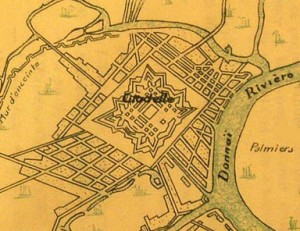

French military assistance also extended to the construction of several new fortifications. The largest of these was the first Gia Định Citadel, built in 1790 by a team of 30,000 labourers under the charge of French engineering corps mercenaries Olivier de Puymanel and Théodore Le Brun to serve as Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s temporary royal capital (Gia Định Kinh). Although built in accordance with the principles of Vauban military architecture, the polyhedron-shaped citadel’s perceived similarity to an octagon and the fact that it had eight gates gained it the popular local name, Bát Quái (“Eight Trigrams”) Citadel.

Located on a 1.2km x 1.2km site corresponding to the area between the modern Lê Thánh Tôn, Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa, Nguyễn Đình Chiểu and Đinh Tiên Hoàng streets, the citadel was constructed from Biên Hòa granite, with 5m high walls and bastions surrounded by a deep moat. It was dominated on its southern side by a large flag tower and the main Càn Nguyên southern gate stood in the vicinity of today’s Đồng Khởi/Lý Tự Trọng street junction, where surviving sections of bastion wall were unearthed during construction work in 1926. The citadel was connected with the royal wharf on the Sài Gòn river by what is now Đồng Khởi street.

This 1793 map depicts the first Gia Định Citadel (1790) and the eastern end of the earlier Lũy Bán Bích city walls (1772)

At its centre (close to the modern Lê Duẩn/Hai Bà Trưng street junction) was the King’s Palace, flanked on its left by the Prince’s Palace. Immediately behind it was the Queen’s Palace, and in front of it was a large parade ground and armoury. Other buildings included an army barracks, a hospital, a wagon workshop, an arsenal, a forge and three gunpowder stores. The citadel was the focal point of a highway network known as the Thiên Lý road, which led west to the Mekong Delta, north west to Cambodia and north east to Huế and Thăng Long (Hà Nội).

His newly-upgraded forces and fortifications gave Nguyễn Phúc Ánh a qualitative military edge, contributing in no small way to his final victory over the Tây Sơn and facilitating his accession to the throne in 1802 as the first Nguyễn dynasty king, Gia Long (1802-1820). He subsequently chose Huế as his royal capital, but Gia Định remained a settlement of great strategic importance and during the first three decades of Nguyễn dynasty rule it was afforded a significant measure of political and economic autonomy under a series of royal Viceroys, the best known being Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt (1763-1832). However, this autonomy subsequently attracted the wrath of Gia Long’s successor Minh Mạng (1820-1841), who after Duyệt’s death in 1832 set about restoring central government control, pointedly downgrading Gia Định to the status of a mere provincial capital.

Later, in a symbolic act designed to discourage any further separatist tendencies after the failed southern uprising of 1832-1835, Minh Mạng had his father’s great royal citadel of 1790 demolished and replaced by a considerably smaller one.

The location of the second Gia Định Citadel of 1837, superimposed on the modern street map

This “Phoenix Citadel” of 1837 stood in the area now bordered by Nguyễn Đình Chiểu, Nguyễn Du, Mạc Đĩnh Chi and Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm streets. It, too, was built in accordance with Vauban principles, though in the shape of a square with 5m high walls and four corner bastions, surrounded by a 3m deep moat.

Although no traces of this second Gia Định Citadel have survived, an almost identical structure – the Điện Hải Citadel (see later post Dien Hai – Da Nang’s forgotten Vauban citadel) – may still be seen today in Đà Nẵng.

The French attacked the south gate of the 1837 Gia Định Citadel in February 1859 (top); the French demolished the Citadel and in 1872-1873 built their 11th Colonial Infantry Barracks on the site (middle); the gatehouses of the former 11th Colonial Infantry Barracks still stand today on the junction of Lê Duẩn and Đinh Tiên Hoàng (bottom)

The Phoenix Citadel survived for just 22 years; following the conquest of 1859, the French razed it to the ground and in 1870-1873 they built a Caserne de l’infanterie (infantry barracks) over its front section. Despite the demise of Minh Mạng’s citadel, the French continued to call the area “Citadelle” throughout the colonial period.

The Caserne de l’infanterie originally contained rows of handsome iron-framed colonial barracks buildings, identical to those which may still be seen today at the nearby Children’s Hospital 2 (the former Grall Hospital).

The front gate of the barracks in the aftermath of the November 1963 coup

Following the Japanese coup of March 1945, they were used briefly to intern French troops. Then in 1956, South Vietnamese President Ngô Đình Diệm renamed the Caserne de l’infanterie as the Thành Cộng Hòa (Republic Citadel) and turned it into the headquarters of his elite Presidential Guard. Consequently the compound suffered serious damage during the coup of November 1963 which deposed him.

After the coup, the remaining military installations were moved out of the old barracks compound and an extension to Đinh Tiên Hoàng street was driven right through the middle of it.

By 1967 Sài Gòn University had taken up residence in the southwest section, while the American Armed Forces Radio Television Service (AFRTS) and the locally-run Việt Nam Television (Truyền hình Việt Nam, forerunner of Hồ Chí Minh City Television, HTV) occupied much of the northeast section. Today the former barracks site is shared between the Hồ Chí Minh City University of Social Sciences and Humanities and HTV.

Despite all of this redevelopment, it’s still possible today to identify the buildings which frame the entrance to Đinh Tiên Hoàng street on the Lê Duẩn junction as those which originally stood either side of the main gate of the 1873 Caserne de l’infanterie – buildings which constitute our last link with the lost royal citadels of Gia Định.

A front view of the 11th Colonial Infantry Barracks in the early 1900s and the same view of the Lê Duẩn-Đinh Tiên Hoàng intersection today

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.

The 1832-1835 revolt is also known as the Le van Khoi rebellion http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%C3%AA_V%C4%83n_Kh%C3%B4i_revolt. It should be noted that the original Phien An Citadel by de Puymanel and Lebrun was so well-built that Ming Mang’s troops, despite far greater in number and better armed than the rebels, could not breach its walls for more than 3 years. It was said that Ming Mang was so upset at the heavy loss of his forces that he ordered the execution of all captured rebels and the complete demolition of the fortress after its defenders surrendered. The fortress was never breached and little that the defenders knew that they would be all later executed by Minh Mang. 1,831 people were killed and buried in a place called Ma Nguy (Cemetery of the Puppets). During the construction of Saigon in late 1800’s, French engineers moved this cemetery to make room for the current Democratic Rounabout (Bùng binh dân chủ) which connects District 1, 3 and 10. On a side note, during the siege, Father Marchand had sent a messenger to Siam to request help but the Siamese naval relief column was intercepted and destroyed by general Truong Minh Giang (one of the most able generals of both Gia Long and Minh Mang) in now near the Mekong Delta city of Long Xuyen. The Siamese expedition army commanded General Bordindeja was also kept in check by general Truong Minh Giang in Svay Rieng, Cambodia and could not link up with the naval column on the Bassac river (Hau Giang) to sail to Saigon http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cPlyQcFAplU. General Bordindeja was so distraught at the complete loss of the Thai vessels and marines under his command that he vowed never to return to Bangkok to face King Rama III. The two generals would later face each other again in the Vietnamese-Siamese War from 1841 to 1845.

The “caserne de l’infanterie” was used to house soldiers and officers of the 11th Colonial Infantry Regiment (Fr. 11e régiment d’infanterie coloniale) guarding Saigon. http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/11e_r%C3%A9giment_d%27infanterie_coloniale. This regiment was in turn divided into 2 battalions – one stationing in Saigon and the other in Thu Dau Mot (or Binh Duong) 30 km north of Saigon. It was this regiment that blew up the gate of Tien Tsin – the fortress guarding Beijing – during the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1901 using French “Melinite” artillery shell, a 5.3 kilograms impact-detonated, thin-walled steel, high explosive type with a time-delay fuse. The fall of Tien Tsin enables the Allies to rush to Beijing and save the besieged westerners from being slaughtered by the Chinese Imperial Army. Saigonese abroad still affectionately refer to this regiment as Ông Dèm RIC (bastardized French for onzième or 11th, RIC is abbreviated for Régiment d’Infanterie Coloniale).