Đồng Khánh, 1885-1888

Since the start of the Tet holidays, news of the death of the King of Annam, Dong-Khanh, has circulated in our city. This sad news was confirmed by the telegram which we publish above.

The king was just 26 years old. He was the son of a Prince named Kien-Thai-Vuong, (brother of King Tu Duc), elder brother of Kien-Phuc whom he succeeded, and half-brother of Ham-Nghi, currently detained in Algeria.

Hàm Nghi, 1884-1885

Let’s recall under what conditions he ascended the throne.

After the attack against General de Courcy in Hue (5 July 1885), the Regent Ton-That-Thuyet fled with the young King Ham-Nghi and raised the mandarins and scholars against us.

A month later, Dong-Khanh, elder brother of the fugitive, to whom the crown should have gone first, was proclaimed king.

Unfortunately, after the events of 5 July 1885, his position was very precarious.

At the time he ascended to the throne, Dong-Khanh was indeed a very slender figure, without authority over his subjects or over foreigners. He could rely neither on the people who had been terrorised by the mandarins, nor on the ruling class of the literati, who had made common cause with Regent Thuyet.

M. Joseph Chailley-Bert, in his book Paul Bert au Tonkin, retraced for us the spectacle of the court at that time:

“His court resembled a desert. The city, the citadel and the suburbs had once  held more than 100,000 people, yet now there hardly remained 30,000. All around the palace rose great buildings constructed to accommodate countless servants or relatives, but now they were empty. In the street of the Ministries, where there once thronged a crowd of mandarins, there was little movement other than a few isolated palanquins. Meanwhile, the few advisers or servants who were retained by the new king had neither notoriety nor serious influence.”

held more than 100,000 people, yet now there hardly remained 30,000. All around the palace rose great buildings constructed to accommodate countless servants or relatives, but now they were empty. In the street of the Ministries, where there once thronged a crowd of mandarins, there was little movement other than a few isolated palanquins. Meanwhile, the few advisers or servants who were retained by the new king had neither notoriety nor serious influence.”

Finally, Paul Bert arrived. King Dong-Khanh gave him a welcome reception and there explained the disrespect which was being shown to his person, and the little authority he had in the eyes of his subjects.

Paul Bert understood that the time had come to raise the prestige of royal authority, and at the same time to assert the influence of France. He transferred to the monarch half the treasure of Annam; the other half was sent to Paris to be converted into piastres bearing Dong-Khanh’s image.

The compound of the Viện Cơ Mật or Privy Council

The meetings of Co-Mat were no longer to be attended by foreign witnesses. Now, only the Résident supérieur M. Bihourd retained the right to attend. Finally, the doors of the palace were no longer to be guarded by French soldiers.

M. Constans and M. Richaud also continued to ensure that in Algeria, the detained former king was still the liberty and honours compatible with our security requirements.

A dispatch from the Governor General registered the fidelity with which His Majesty Dong-Khanh had fulfilled its obligations to us, and the sympathy of pledges which our country had constantly received from him. This was not banal praise, but recognition of a truth understood long ago.

On 24 April 1887, in an interesting note published on King Dong-Khanh, M. Petrus Ky said the following:

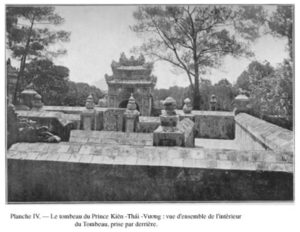

The tomb of Kiên Thái Vương Nguyễn Phúc Hồng Cai (1845-1876), 26th son of Emperor Thiệu Trị and father of three emperors – Đồng Khánh, Kiến Phúc and Hàm Nghi (BAVH)

“The present king was loved and respected by his brother Kien-Phuc, in a manner which was unusual in Asian royal families. When he was out walking, the late king affectionately carried with him a portrait of his elder brother. During his youth, Dong-Khanh lived in a special residence called the Chang-Mong-Duong, where he devoted himself passionately to study. Enthralled day and night by the love of reading, he hardly ever drew himself away from his office. He was therefore well versed in the philosophy, history and literature of the Far East, much more so even than an average member of the literati.

The only distraction he permitted himself was the exercise of horse riding. Tu-Duc, seeing how he studied so hard, permitted him to go three times a month to the palace of the Noi-Cac (royal office) to expound on the classics, and there to write literary compositions and assist in the development of the edicts and administrative acts of the kingdom.

He was distinguished at these sessions by the quickness of his mind in estimating the value of both men and things.

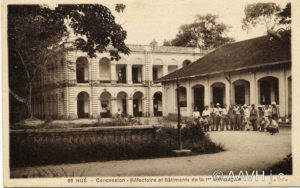

The French Concession in the Citadel

This young prince did not have, it seems, the ambition to ascend the throne. Also, when disagreements arose between the mandarins of the court, or abuse of authority needed to be suppressed, he took sides fairly, with no regard for self-interest.

Living among the people, he was also able, by personal observation, to come to appreciate the miserable state of the population.

As for his personal conduct, he observed between his brothers and his parents the perfect harmony prescribed by Confucius. This young prince was very intelligent and affable; he readily adopted foreign customs, in a manner which surpassed that of many of his countrymen.

I speak as a personal witness, from what I have seen and heard.

From the particular point of view of French interest, it is very fortunate that Dong-Khanh occupied the throne.”

Đồng Khánh, 1885-1888

We have before us a photograph of the King of Annam published in the weekly French newspaper L’Illustration. His face expresses sweetness rather than firmness.

He sits on a richly carved throne, hands resting on his knees. He wears the Annamite costume: a robe embroidered with silk and gold, wide silk trousers, and bare feet in slippers supported on a pedestal. His head is covered with a traditional turban.

France will stage for this young prince a funeral worthy of him and of the people who observe to such a great extent the worship of the dead.

And now we can all exclaim: “Dong-Khanh is dead! Long live Thành-Thái!”

Đồng Khánh, 1885-1888

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group page Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.